1

Twilight of Prosecutions of the Global Auto-Parts Cartels

John M. Connor

Emeritus Professor

Purdue University

and

Senior Fellow

American Antitrust Institute

July 17, 2019

2

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The Auto-Parts Supercartel comprises 70 to 80 interconnected, international, automotive inputs, bid-

rigging schemes detected mostly during 2008 to 2017. Almost half of the convicted companies were

Japan-based parent firms or their subsidiaries. The connections among the cartels are provided by

overlapping corporate memberships and by the targets of collusion, 17 Original Equipment

Manufacturers (OEMs) of automotive vehicles.

Experienced antitrust officials have asserted that the Supercartel is the largest constellation of cartels

ever tackled by the world’s antitrust authorities. The truth is that “it depends.” In terms of the

number of firms and individuals convicted, it is indeed the biggest; measured by affected sales and

monetary penalties, it appears to be a close second.

The origin of these cartels is rather mysterious. Most cartels are formed after a sustained period of

falling prices and profits, but not Auto-Parts. Outside of East Asia, auto manufacturers have long

placed strong pressures on their suppliers to reduce prices of their inputs through competitive

bidding. In Japan, customary OEM loyalty to suppliers began to break down in 1999, and the great

majority of the cartels were launched during 1999-2006. Did the assemblers push too hard on price

reductions in the early 2000s, and thereby trigger supplier collusion to cope with an existential

threat?

At last count 18 jurisdictions vigorously prosecuted this supercartel, which demonstrated exceptional

duration, global reach, size, and injuriousness. Estimates for affected commerce of the Auto-Parts

supercartel range from $3.2 to $5.0 trillion. There are few reliable estimates of overcharges, but

averaging the few preliminary estimates suggests that injuries are in the range of $0.6 to $1 trillion.

Antitrust enforcement aimed at this supercartel is nearly complete as of early 2019. Canada has

definitely closed all Auto-Parts cases. In the United States, because of the U.S. five-year statute of

limitations, the DOJ’s investigations of auto-parts cartels began winding down in late 2015.

Corporate indictments elsewhere appear to be over. Although it is possible that the DOJ may nab a

couple of the 60 Auto-Parts fugitives and seek their extradition, further convictions of individuals in

the United States are unlikely. The status of several mature EC investigations suggest that most have

been closed. Brazil and Mexico still have 20-plus investigations open in 2019.

Among other observations, the Auto-Parts cases bring into focus the relationship between monetary

penalties and jail time for cartelists. For example, more than $20 billion in penalties has been

imposed worldwide on nearly 300 corporate cartelists. In North America about half of those

penalties were extracted through settlements from class-action damages suits, which is slightly higher

than the historical average. To be sure, these penalties provide some measure of restitution for the

victims of cartel crimes. But even if corporate monetary penalties rise well above the current $20

billion total; deterrence of collusion is highly unlikely. For deterrence purposes, indictments and

sentencing of hundreds of individuals in the automotive industries may have lingering effects on the

ethical behavior for would-be cartel managers.

3

Twilight of Prosecutions of the Global Auto-Parts Cartels

John M. Connor

July 17, 2019

“The auto parts investigation is the largest criminal investigation the Antitrust Division has ever pursued, ....”

(Speech by Sharis A. Pozen, U.S. DOJ, January 30, 2012)

I. Introduction

Since at least the year 2010, price-fixing investigations have been launched by at least 26 antitrust

authorities around the world targeting hundreds of manufacturers of automotive parts sold to

almost all of the world’s largest auto-assembly makers (OEMs).

1

In addition to automotive

components proper, some members of the cartels sold services to OEMs that aided the OEMs in the

distribution of finished vehicles. Some cartels conspired on direct sales of aftermarket parts or

systems of parts to auto-parts stores. Finally, the cartelized parts were resold to buyers after being

incorporated into finished vehicles; indirect purchasers include dealers (auto retailers), fleet rental

companies, and households that purchased vehicles (consumers or “end-users”).

Some of the early investigations developed from complaints of OEMs to antitrust authorities, but

the vast majority were uncovered through corporate leniency applicants.

2

Cooperation by amnesty

applicants help unearth otherwise clandestine details about how, when, and where the cartels

operated.

By 2019, nearly all antitrust investigations of the cartels were completed, and penalization has slowed

to a trickle (Greimel 2016). After 15 years of government prosecutions and 18 years of private-

damages actions, the time seems ripe to round up what has been revealed about the formerly

1

jconnor@purdue.edu. This paper is the third and likely final working paper in a series of papers on the Auto Parts

cartels. The second version is entitled: Is Auto Parts Evolving into a Supercartel?: AAI Working Paper No. 13-04 (August 28,

2013) [http://www.antitrustinstitute.org/~antitrust/sites/default/files/WorkingPaper13-04.pdf], which in turn is a

considerably revised version of Multiple Prosecutions Point to Huge Damages from Auto-Parts Cartels: AAI Working Paper 12-08.

(December 13, 2012). [http://ssrn.com/abstract=2190200]. The present version sums up on legal-economic

developments through February 2019. I thank Bert Foer, Diana Moss, and Jon Cuneo for constructive comments on

earlier drafts of this Working Paper. The cartels so far identified are characterized by a high degree of supply

substitutability in the sense that the products are made in plants controlled by parts manufacturers that are rivals in

supplying interconnected systems that are designed to be integrated by a single control mechanism. For example, Thermal

Systems covers a complicated array of pumps, fans, vents, filters, compressors, sensors, displays, and driver controls wired

together to heat and cool the air in the passenger cabin. Other products like bearings are less complicated. Not all auto

parts makers are likely to be proved to be in collusion; an announcement by Magna (2013) appears to rule out the auto-

tooling industry. Similarly, although the highly concentrated marine Auto Shipping industry is suspected of cartel conduct,

the atomistic overland shipping industry has not been investigated.

2

These include applications for full amnesty (or immunity from prosecution), amnesty-plus, and partial amnesty.

4

clandestine Auto-Parts Supercartel and to try to assess the breadth and effectiveness of antitrust

enforcement.

3

In this report, I first address the issue raised by the quote by Sharis Pozen above: In what respects

are the group of related Auto-Parts cartels the biggest seen in the history of contemporary price-

fixing schemes and prosecutions thereof?

4

Then I examine (1) the historical origins of the

discoveries of these cartels and their prosecutions; (2) the role of industry structure in facilitating

collusive conduct; (3) geographic location of collusion; (4) duration of collusion; (5) antitrust

prosecutions of the cartelists worldwide; (6) limited information on the severity and recovery of

penalties; and (7) concluding observations.

5

II. Size Measures Are Impressive

The Auto-Parts Supercartel is well on its way into the cartel record books, though it is not the biggest

in all respects. With nearly all criminal investigations exhausted and private antitrust litigation

concluded, the shape and size of these illegal schemes is known with a fair degree of certainty.

The U.S. DOJ’s top antitrust official called Auto-Parts the “largest criminal investigation” ever

pursued by the Division. European Commission officials reportedly have referred to Auto-Parts as

the “Cartel of the Century” (Niemeyer et al. 2018), and antitrust experts agree that it is one of the

biggest groups of cartels ever prosecuted. Antitrust prosecutors and judicial systems uniformly treat

the dozens of individual automotive-inputs cartels as belonging to one grand, overarching set of

interrelated collusive schemes. – a Supercartel. At the core of the Supercartel are archetypal

precision components supplied to manufacturers that assemble and brand finished vehicles – the

OEMs. At the periphery are other industries that supplied inputs indirectly (e.g., Polyurethane Foam)

or post-manufacturing services (Ro-Ro-Auto Shipping).

6

Six dimensions of the size of Auto-Parts enforcement challenges have been proposed. First, Pozen

(2012) cited three: (1) the “scope,” (2) the “affected commerce,” and (3) the high dollar amount of

corporate fines being imposed (Pozen 2012).

7

“Scope” can refer to product breadth or to (4)

geographic extent. Second, a retrospective article in a legal-economics journal suggests that the Auto-

Parts cartels were perhaps the largest U.S. antitrust litigation by citing evidence on two more

indicators: (5) the high number of companies charged (48 at the time) and (6) the large numbers

executives indicted (then 65) (Burtis et al. 2018).

8

3

Moreover, it is now becoming clear that since the beginning of the Trump administration, the U.S. anticartel effort has

been throttled back (Connor 2019a). This is not the case about the non-U.S. antitrust authorities, where assertiveness

seems less diminished.

4

Pozen’s DOJ colleague Scott Hammond reiterated in a Detroit speech in March 2013 that Auto-Parts will be the largest

cartel conviction in the history of the Division [http://bearingcode.com/newupdates2013.html].

5

Eight tables of detailed data are at the end of this paper.

6

In other words, there is room for disagreement by regulators or those who chronicle this supercartels as t the precise

list of products to be included. This report may take a rather inclusive view of the Supercartel’s composition.

7

I interpret the term “scope” to mean the number of markets with non-substitutable goods that were investigated or

convicted. A Global Competition Review commentary agrees with (or perhaps paraphrases) Pozen. “The Auto Parts

investigation, the largest ever cartel investigation in terms of the number of corporate prosecutions....” (Higbee et al

2018). Pozen also cited a possible fourth characteristic of size, namely, the substantial coordination of the DOJ with the

Japan FTC, the EC, and the Canadian Bureau of Competition. This possible indicator of size is not transparent and

therefore not measurable with public data.

8

Burtis et al. (2018) also cite the number of parts products involved (“more than fifty”), but this is scope.

5

It is apparent that when writers refer to the automotive-parts cartels they are employing a supercartel

concept. Size comparisons are facilitated by my previous work in conceptualizing supercartels

(Connor 2013). Most of the many intertwined and overlapping auto-parts cases clearly seem to

qualify as the world’s third supercartel, following the infamous Bulk Vitamins cartels of the 1990s

and the Banking collusion scandals a decade later (Connor 2008, 2014).

9

Supercartels are unique and

uniquely large. They are: (1) global in scope, (2) have a large number of distinct products (i.e.,

separate cartels) that have partially overlapping corporate membership, and (3) direct their price

fixing at customers in one vertical production-distribution channel. In short, supercartels have

wheels within wheels.

10

(1) Scope

When enforcement scope is mentioned, it most commonly refers to the number of separate markets

affected by collusion. More than 200 auto parts identified by unique SKUs (part numbers) were

subject to bid rigging. However, many of the parts were bundled into integrated “systems,” and it

was these systems that were the objects of bid rigging.

11

It now appears that no fewer than 70

separate Auto-Parts and related automotive markets were investigated for collusion. By mid 2019, 70

Auto-Parts cartels had been penalized, and ten cases were remaining resolution.

12

However, 70 to 80 is slightly shy of the number of Banking supercartel markets, which is 88. Auto-

Parts is the second largest number of product markets of any of the historical supercartels.

13

Moreover,

the evolving Generic-Drug cartels prosecutions could easily exceed Auto-Parts.

14

(2) Affected Commerce

The Auto-Parts cartels had enormous dollar sales during their collusive conduct periods.

Unfortunately, reliable information on sales of many automotive components and systems seem to

be proprietary within the industry. Estimates of affected commerce can be obtained for about three-

fifths of the cartels. Some estimates from decisions of antitrust authorities (e.g., Trucks in South

Korea) are fairly precise, as are some from public sources (e.g., Trucks in the EU), are fairly reliable.

While a few market estimates are quite rough, affected sales for about 49 of the cartelized markets

amount to $3.2 trillion (measured in current or nominal dollars). Projecting these sales to the total of

the 70 condemned cartels and adjusting for inflation would likely to raise sales to the $4 to $5 trillion

range.

15

9

Admittedly, decisions regarding the product or temporal boundaries can be tricky and require expert judgment.

10

Readers, please note that this is not a bad pun about the auto-parts cartels: no wheel-parts makers have been accused.

11

For example, the cartel often called Occupant Safety includes safety belts, air bags, steering-wheel assemblies, g-force

sensors, radar, lidar, ultrasonic detectors, automatic brakes, controls for setting these components, connective wiring,

computers, and in the most advanced cars software to integrate “autopilot” and self-driving capabilities.

12

As of early 2019, a dozen or so of the 113 companies are still awaiting to be fined in in the near future by Brazil and a

few other tardy antitrust authorities. However, many have been dismissed from prosecution by antitrust authorities that

do not announce case closings.

13

By definition an ordinary cartel affects only a single well-defined market and industry. I judge that since 1990 only

three other supercartels can be identified: Bulk Vitamins, Banking, and probably the Lava Jato cartel centered in Brazil

14

A recent press report says that 300 drugs are currently under investigation, and quoted an experienced antitrust

attorney saying: “This is most likely the largest cartel in the history of the United States,” Nielsen said” (Rowland 2017).

15

No matter the exact figure, cartel penalties will average less than 1% of affected commerce – a very low severity by

historical standards.

6

Despite this large sales estimate, it is not certain that the Auto-Parts cartels are the highest in sales,

mainly because the Banking supercartel, though bigger, is not comparable.

16

(3) Geographic Extent

Scope could possibly refer to geographic extent of prosecutions. The affected commerce of most of

the Auto-Parts cartels was geographically global in scope. Forty-nine of the proven-guilty Auto-Parts

cartels (70%) were organized on a global scale

17

– a much higher proportion than for international

cartels in general.

18

Consequently, the number of antitrust authorities engaged in Auto-Parts

investigations was very large.

Besides North America and the EU,

19

virtually all of the guilty Auto-Parts cartels colluded in Asia

(seven nations), predominantly East Asia plus a few in South Asia and Turkey. Fifty-three of the 70

penalized cartels (76%) operated in the United States and at least 28 of the convicted cartels (40%)

had sales in the EU (and several more EC decisions are in the pipeline). It also appears that they

infected the auto-assembly industries in Australia, Mexico, Brazil and South Africa.

20

In total, the

national assembly industries of 29 nations were affected by collusive conduct, and 16 antitrust

authorities investigated at least one cartel (including five EU NCAs). However, the number of

antitrust authorities that prosecuted Banking was 33, so Auto-Parts is not close to a world record by

this measure of scope.

21

(4) Number and Amount of Monetary Penalties Imposed

Within three years of the first raids in September 2013, a total of almost $2.0 billion in corporate

fines had been imposed.

22

Five years later, monetary penalties had reached $20.7 billion – second in

terms of a world record.

23

However, some extreme projections of penalties in Diesel Emissions imply

that Auto-Parts cartels’ penalties will surpass the Banking supercartel, which had $30 billion in

penalties.

(5) Number of Corporate Cartelists Indicted

16

Going back to the 1990s, the previous record-sales commodity cartels were those in Bulk Vitamins; Auto Parts

surpasses the Vitamins supercartel by quite a bit (Connor 2008). Sales of the Banking supercartel are definitely higher, but

historically economists do not compare financial sector sales with industrial real products (Connor 2014). Better

measures like value added are not available.

17

Global cartels are those that fixing prices on two or more continents; operations on three or four continents are

typical.

18

In the PIC data set, only 17% of the convicted cartels were global in geographic scope (Connor 2014: 12). But in Bulk

Vitamins, 15 of the 16 (94%) were global.

19

Assembly of 100,000 or more light vehicle units annually in 2010 covers 15 of the EU Member States.

20

The major exceptions were Algeria, Argentina, and Egypt.

21

Air Cargo reached 15.

22

In December 2012, I predicted that fines and other penalties would probably reach at least $5 billion. “At this rate

these cases are evolving, there is a good chance that monetary penalties eventually may climb to $5 billion or more.”

(Connor 2013: 2).

23

Casting back 30 years, the current world record holder is the LIBOR and related Foreign Exchange supercartel, which has

accumulated $32.8 billion in penalties.

7

I expect about 450 to 500 corporate cartelists eventually to be indicted in Auto-Parts. Already there

are 320 corporate fines imposed on the cartels’ corporate participants

24

, ten more signed consent

decrees, 11 grants of immunity, and 113 companies still under investigation.

25

As of early 2019, a

scores of companies are still awaiting to be indicted or fined in in the near future by Brazil and a few

other tardy antitrust authorities. The number of corporate indictments in Auto-Parts is clearly a world

record.

26

(6) Number of Individuals (Cartel Managers) Indicted

The number of individuals indicted worldwide in Auto-Parts reached 190 by mid 2019. Of the 190

indictments of executives, 169 (89%) were sought by the U.S. DOJ.

27

The individuals indicted in the

Banking supercartel totaled 105, so Auto-Parts is by far in the leading supercartel by this metric.

Individual U.S. fines are token (median $20,000), but custodial sentences are the highest recorded.

The DOJ has so far imposed prison penalties on 68 Auto-Parts executives. As of mid 2019, total

U.S. incarceration is 1175 months (an average of 17.3 months for each incarcerated individual).

About 60 executives indicted by U.S. prosecutors (36%) are fugitives awaiting sentencing.

28

An

additional 100 Auto-Parts managers involved in four cartels have been indicted by Brazil.

29

III. Origins of Collusion and the Investigations

A. Remote Causes

The remote causes of the price-fixing behavior may lie in the customary organization of many

Japanese suppliers of components to brand-name manufacturers; these organizations are called

keiretsu. Vehicle-assembly manufacturers historically fostered close, trusting relationships with a

small number of relatively small auto-parts suppliers (Dawson and Kendall 2013). Auto

manufacturers often have significant equity in their suppliers, work closely together on technological

standards and design, share proprietary technology, and “enjoy the right of first refusal for newly

developed technology” (ibid.). In other words, members of a keiretsu share a consensus view that

incumbent suppliers deserve protection from competitive rivalry.

24

This the count of fining decisions, not companies; because some companies were fined across several cartels, there are

only 151 unique parent companies or parent groups receiving fines (Connor 2019). In Banking, the number of cartelists was 222

(Connor 2014).

25

Historically 95% of indicted hard-core cartelists are convicted. This does not include at least a dozen guilty amnesty

recipients likely to be penalized in privates suits soon. Note that this is a count of penalties and likely penalties, so serial

colluders are double counted.

26

The Banking supercartel had 222 banks indicted (Connor 2014, 2016b).

27

There is a small amount of double-counting of the executives, because a dozen or more were indicted for multiple

counts of bid rigging in multiple schemes. Three individuals that were indicted, after substantial cooperation, had their

charges were dismissed.

28

The U.S. justice system will typically keep looking for these fugitives for up to ten years, but nearly all of them –

especially those near the end of their careers – will evade arrest and extradition. If one counts fugitives as having zero

months in prison, then the 128 indicted executives were sentenced to a mean average of 9.2 months in prison.

29

Brazil will likely charge more than 200 company managers in total, though imprisonment is not customary, and their

fines are usually paid by their employers. Japanese prosecutors sought and received criminal sentences for nine

executives in the Auto Bearings cartel; however, the Japanese courts suspended incarceration or converted the three-year

prison terms to probation.

8

Keiretsu are a modern-day, looser version of the Japanese zaibatsu, which flourished from the 1920s to

1945, and of which 16 were formally dismantled and outlawed in 1946-1947 by U.S. occupation

authorities (Caves and Uekusa 1976). Zaibatsu and keiretsu

30

can be described as conglomerates

31

with

important horizontal and vertical relationships that may be informal, contractual, or reinforced by

cross ownership; they may be united by a holding company that controls a major bank.

32

Many

zaibatsu were revived or tolerated by the authorities in the 1950s in order to supply the allies in the

Korean War. Several keiretsu were newly formed or first began growing rapidly at this time.

33

Cracks in the keiretsu system serving the automotive sector first began around 1999 when Renault

took over struggling Nissan (Dawson and Kendall 2013). In June 1999, the Renault-Nissan Alliance

appointed a new hard-charging CEO, Carlos Ghosn, who emphasized extreme cost-cutting

measures as a principal strategy to improve profitability.

34

Nissan’s keiretsu was disbanded and

replaced by open-source bidding for Nissan parts and components. In order to stay price-

competitive, Toyota and Honda shifted to open bidding too, initially outside of Japan. Collusion in

four Japanese auto-parts cartels began in the year 2000.

The second blow to the keiretsu system occurred in 2005 when the Japanese Fair Trade Commission

instituted a formal corporate leniency program for cartelists (JFTC 2005). This program, modeled on

programs adopted by other antitrust authorities as early as 1993, offered powerful monetary

incentives for cartel participants to confess their own transgressions, denounce fellow conspirators,

and normally cause the collapse of the cartel. “[Japanese] companies fingered in other cartels

worried they’d be burned again if they didn’t step forward,” said Kazuhiko Takeshima, former head

of the JFTC (ibid.). The leniency program was contrary to widely held notions of oligopolistic

cooperation among leading Japanese businesses, especially keiretsu members. In January 2009, the

JFTC and three other antitrust authorities opened investigations into price fixing of

undersea/underground cables; two of the suspects were Furukawa Electric and Sumitomo Electric.

30

The major difference between the two seems to be that zaibatsu were controlled by and named after extended families

(Mitsui, Mitsubishi, Sumitomo, etc.), whose assets were seized in 1946, whereas keiretsu are organized by a single final-

product manufacturer or manufacturing group. Additionally, the former tended to emphasize tight vertical integration by

a single supplier, whereas the latter accommodated a small number of suppliers that had a degree of rivalry in R&D.

31

Besides a big bank, holding company, and international wholesale trading firm, each Keiretsu usually includes insurance,

shipping, and a wide variety of manufacturing companies.

32

For example, the Tokai (or Toyoda) Group is led by the Tokai Bank and includes the Daihatsu, Suzuki, and Toyota

auto manufacturers. Toyota sponsors a supplier group known as Kyohokai that encompasses 200 parts suppliers (Jie et

al. 2013). While ostensibly an information-sharing organization, meetings and outings offer opportunities for collusion.

After being convicted for price fixing of wiring harnesses and related safety equipment in 2011, Fujikura Ltd., after

strengthening its internal antitrust compliance program, withdrew from Kyohokai activities. The major change from the

1920s is that family control has been replaced by holding-company shareholder control.

33

Toyota and Honda are examples. Toyota Group owns in Toyota Motor Corp., and TMC has majority or controlling

shares in auto-parts suppliers Denso Corp., JTEKT Corp., Tokai Rika Co., Kanto Auto Works, Aichi Steel Corp, Aisin

Seiki Co., Ltd and others. Toyota’s bank was known as Toyo Trust and Banking until 2001 when it merged with two

other banks to become UFJ Bank (now Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group, Inc.). As of early 2013, Denso and Tokai Rika

Co. were convicted and JTEKT was a suspect in bid rigging. Honda owns 15% of Yamashita Rubber Co., a defendant in

the Rubber Anti-Vibration Parts cartel.

34

Carlos Ghosn was initially appointed COO of Nissan Motors by Renault in June 1999 and became CEO and

President of Renault in 2005. In the late 1900s he earned the sobriquet “Le Cost Killer” after restoring Renault to

profitability through plant closings and other cost-cutting measures. He is co-author of the book Shift: Inside Nissan's

Historic Revival (http://uk.askmen.com/celebs/men/business_politics_60/76_carlos_ghosn.html). In October 2016,

Mitsubishi Motors joined the Renault-Nissan Alliance. In 2019, Mr. Ghosn was arrested and imprisoned in Japan for tax

evasion.

9

Both companies made auto wiring harnesses as well as cables. Both companies sought and received

leniency from the JFTC for offering full cooperation in the Wiring Harness cartel (ibid.).

35

They may

have applied for immunity elsewhere; neither company has yet been indicted by the DOJ for price

fixing in Wiring Harness.

B. Proximate Events

How the current wave of auto-parts antitrust prosecutions began is uncertain (Bird and Bird 2012).

One story is that an EC investigation was prompted by the complaints around 2009 of several EU

automobile manufacturers (“OEMs”); the OEMs said that some manufacturers of automotive wire

harnesses were refusing to bid competitively on Requests for Proposals issued by the OEMs. This

scenario is a typical way of detecting a cartel before leniency programs became nearly the sole

method in the late 1990s. Other sources say that in late 2009 a whistle-blower approached the

Canadian Competition Bureau (“the Bureau”) to apply for amnesty (Johnson Winter 2012). The

Bureau sent requests for information to five other auto-parts suppliers and shared its findings with

other antitrust authorities. If this event was the initial impetus for the Auto-Parts investigations, it

reinforces the widespread dependence of antitrust authorities on leniency programs to generate

cartel cases.

Whatever the initial impetus, in late February 2010 three antitrust authorities conducted coordinated

international raids of auto-parts companies’ headquarters worldwide. The Japan Fair Trade

Commission (“JFTC”) raided DENSO offices in Japan, and the Antitrust Division of the U.S.

Department of Justice (DOJ) raided three auto-parts manufacturers, including DENSO

36

. The

industry or company targets of the EC’s raids in February 2010 were initially unknown, but later

revealed to be the EU headquarters of four wire-harness manufacturers, including DENSO.

37

Spokespersons for the JFTC and DOJ later announced that their raids were part of a wide-ranging

investigation of collusion beginning as early as January 2000 in several auto-parts industries.

Convictions began in late 2011.

38

The U.S. DOJ fine announced in September 2011 in Wire Harness

was the first in Auto Parts; Japan was the second authority to fine an Auto-Parts cartel, also Wire

Harness, in January 2012.

In early 2010, the DOJ, EC, and JFTC initially raided manufacturers of three auto parts: Wiring

Harnesses, Fuel Senders, and Instrument Panel Clusters. Probably aided by Amnesty-Plus programs

39

,

further cartels were investigated: Aftermarket Sheet Metal

40

in 2010; Aftermarket Auto Lights in July

2010; Occupant Safety Systems and Auto Refrigerants in February 2011; Auto Bearings, Aftermarket Auto

35

Under “Amnesty-Plus” a company guilty of price fixing in industry A, but which does not qualify for immunity in that

cartel (“Cartel A”), can confess its involvement in a cartel in industry B, offer evidence and full cooperation, and qualify

for full amnesty in Cartel B as well as enhanced leniency in Cartel A.

36

Besides Canada, other early movers may have included South Korea and Australia.

37

The four targeted firms were Leoni AG, S-Y Systems, Yazaki Corp., and DENSO. This history is summarized in Part

D. of the 2

nd

Consolidated Complaint, In re Automotive Parts Antitrust Litigation (August 2014).

38

The U.S. DOJ fine announced four Auto-Parts fines in 2011 the first in February 2011 in Aftermarket Auto Lighting;

Japan was the second authority to fine an Auto-Parts cartel, in Wire Harness, in January 2012.

39

The DOJ’s Amnesty-Plus offers immunity to company under investigation for price fixing if it is the first to supply

information about a second cartel about which the DOJ has no information

40

This cartel was apparently discovered by U.S. private plaintiffs, and the role of government investigations, if any, is

unclear.

10

Lights

41

, and Small Electric Motor Components in July 2011; New Auto Lights in March 2012; Thermal

Systems in July 2012; and Auto Marine Shipping in September 2012. Eventually, up to 80 auto-parts and

related cartels were detected (see list in Table 1).

42

The Canadian Competition Bureau was likely involved in the Auto-Parts investigations from about

2009. By about 2012, Canada was joined by the Australian, Mexican and South Korean antitrust

authorities, and all seven were cooperating with each other. Later, the German Federal Cartel Office,

China, South Africa, South Korea, Singapore, and Brazil detected the global Auto-Parts cartels and

some unique domestic cartels operating in their own territories. That makes 12 jurisdictions

representing 40 nations, which I believe is the second-largest number of cartel-prosecuting antitrust

authorities.

43

Press reports and some cartel-fine decisions have identified several amnesty recipients. Furukawa

Electric Co. was granted immunity in the Wiring Harnesses cartel by the JFTC; Denso Corp. was

granted immunity in the Thermal Systems cartel by the JFTC; JTECK Corp. was granted immunity in

the Auto Bearings cartel by the JFTC; DENSO got a free pass in the EC’s Thermal Systems, Alternators,

and Spark Plugs prosecutions; Sumitomo Electric was awarded amnesty by the U.S. and EC

authorities; VW’s MAN Group was immunized in Trucks ;Mitsui’s MOL was the EC’s (and probably

the DOJ’s) immunity recipient in Auto Shipping. These companies saved billions of dollars in fines.

Doubtless a few more leniency and “leniency-plus” recipients will be revealed in a few years.

44

Clearly, close cooperation and coordination among these far-flung antitrust authorities has greatly

aided in the rapid dissemination of information needed to begin the multiple investigations.

Consider this statement by experienced antitrust experts on investigations in Canada:

“Massive enforcement resources appear to be at play in the ongoing auto parts inquiry which, from

early estimations, appears poised to become the biggest cartel case in history. From documents filed

with the Ontario courts, we know that the Bureau’s investigation began with the wire harness raids

in February 2010 and has grown exponentially since then. The size of the Canadian inquiry is

remarkable — as of October 2011, the Bureau claims to have:

• 10 co-operating parties in the inquiry;

• issued at least 15 “target” letters and numerous subpoenas (“Section 11 orders”); and

• granted 164 markers to its co-operating parties across a broad range of products” (Low and

Halladay 2012: 4).

The last figure is particularly impressive and would, under normal circumstances, reflect years of

enforcement efforts. Clearly it encapsulates the enormous scope of the automobile manufacturing

supply chain, and the effects of “amnesty plus” applications”. However, the 164-product claim may

41

This cartel was apparently discovered by U.S. private plaintiffs, and the role of government investigations, if any, is

unclear.

42

The vast majority of the 80 Auto-Parts cartels are parts/components manufacturers with overlapping membership in

schemes that rigged bids against OEMs. However, a few fail to meet the previous definition. For example, auto-parts

distribution in India and auto importers in Indonesia were not organized by manufacturers; leasing autos in Switzerland

was comprised of subsidiaries of OEMs, not suppliers. Finally, a few cartels (in Spain, Korea, Turkey, and Pakistan)

comprised of OEMs colluded on the selling or rental prices of cars, not parts.

43

The largest is the global cartels Air Cargo (13 authorities) (Connor 2019).

44

A complete list awaits several probable EC decisions and developments in private U.S. suits.

11

be exaggerated by failing to group many of the items into the integrated systems that OEMs used to

issue tenders.

45

The number of well-defined Auto-Parts markets is in the 70 to 80 range.

C. The Belated German Diesel Emissions Scandal

The most recent, and still largely unresolved, Auto-Parts investigation was initially known as the

German Diesel-Engine Emissions case (a/k/a “Dieselgate” and “BlueTEC”). Initially focused on

fraudulent statements to environmental regulators in Europe, the scandal has moved beyond

German-based auto and parts makers, beyond conduct just the EU, and by touching upon

allegations of collusion has moved beyond simply fraudulent misrepresentation of the extent of

pollution created by diesel engines.

The scandal was unveiled in May 2014 as investigations of the California and U.S. environmental

protection agencies were launched into illegal claims (and mislabeling of) nitrous oxide emissions

from certain VW diesel motors (Connor 2017).

46

These agencies found evidence that as early as 2008

VW had inserted software into electronic control devices that intentionally “defeated” accurate

measurement of NO

2

emissions; that is, intentional distortion of pollution testing had gone on for at

least ten years and perhaps longer.

47

By the summer of 2015, federal U.S. environmental regulators

were threatening to withhold permission for VW to sell 2016 diesel-engine cars until discrepancies

over emissions levels were resolved (DOJ 2018). As late as July 2015, internal communications show

that senior VW executives agreed to continue trying to deceive those regulators. Finally, on

September 3, 2015, VW officially admitted that it had installed defeat devices on its diesel cars.

The legal repercussions for VW have been severe (ibid.).

48

In March 2017, VW AG pled guilty to

defrauding U.S. and California environmental agencies and violating the Clean Air Act. It paid a U.S.

civil fine of $2.8 billion. Other U.S.-imposed mandatory cash restitution of $5,000 to $10,000 per

vehicle cost VW an additional $17.5 billion. Since then nine VW executives have been charged

criminally. For example, Oliver Schmidt and James Liang were sentenced to prison and in 2019 were

serving sentences of 84 and 40 months, respectively. On May 3, 2018, an indictment of former VW

CEO Martin Winterkorn was unsealed charging him and the entire Management Board of VW with

criminal conspiracy to defraud the United States (ibid.). Several of those charged are fugitives. As of

May 2019, VW has paid $33 billion in fines and compensation to buyers of affected vehicles,

including fines by German State Prosecutors and the Dutch and Italian antitrust agencies. While

representative actions have been filed, most EU buyers remain uncompensated.

49

Suits by diesel car

owners in the EU are demanding $11 billion. Besides fraud indictments, Fiat Chrysler and Renault

45

Many of these parts may be available separately for used auto repairs, but the multi-part systems contained in Requests

for Proposals are the appropriate product markets for bid rigging against OEMs.

46

Initial emissions discrepancies on VW cars were discovered in 2013 tests by the U.S.-based International Council on

Clean Transportation, which informed the California and U.S. environmental authorities of the results. In September

and October 2015, a German auto club found excessive emissions from diesel motors on certain models of new cars

sold by VW, Renault, Volvo, Jeep, Fiat, Hyundai, GM-Opel, Mazda, Ford, Mercedes, and Citroen (The Guardian 30 Sept.

2015).

47

An unconfirmed report says that one former employee told French prosecutors that cheating by Renault on emissions

tests had been in place since 1990 (TheLocal.fr 16 March 2017).

48

For VW’s managerial response to Dieselgate, see Jung and Sharon (2019).

49

“In Europe, VW refused to settle with governments or consumers in Germany, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain,

Switzerland, and the United Kingdom, and treated court cases that arose there as a nuisance and waste of time” (Jung

and Sharon 2019: 8).

12

have had large “voluntary” recalls of their diesel cars, and Porsche executives are under investigation

for bribery and tax evasion (France 24 May 28, 2019). In 2019, authorities in 21 jurisdictions are

investigating violations of environmental laws.

The status of antitrust investigations into diesel emissions is more difficult to gauge. Three antitrust

authorities criminally fined VW or its managers (the DOJ, Netherlands, and Italy) about $6 million

(EU 2019). The German Federal Cartel Office and the EC competition-law directorate are

investigating whether scores of “technical committees” were in fact platforms for quantity-reducing

collusion. One set of allegations concerns limiting the sizes of tanks that contain emissions-cleansing

chemicals for diesel motors. After Daimler applied for leniency, the EC issued a Statement of

Objections to three auto manufacturers (Daimler, BMW, and VW) in April 2019; severe fines on

two or three of the auto makers are expected in 2020.

50

The antitrust authorities of Australia and the

Netherlands are investigating.

In this report, because it is unclear whether fraudulent conduct by auto makers and parts

manufacturers (notably Robert Bosch GmbH) arose from or is linked to collusive conduct,

monetary fines and cash compensation related to diesel emissions will be shown and discussed

separately from other antitrust penalties (see Table 7).

51

In any case, Dieselgate has ensnared seven

of the world’s leading automobile manufacturers and two of their suppliers; monetary penalties

(almost all non-antitrust) to date amount to an extraordinary $31.8 billion, with VW bearing the

brunt.

IV. Industry Structure and Conduct

A. The Auto-Parts Cartels Are Historically Unusual

If one goes back 30 years, the number of auto-supply industries convicted of illegal cartel behavior is

rather small, given the large size of the automotive sector. I have scoured a large scale data set of

international cartels

52

and found ten

53

that for various reasons do not, in my judgment, qualify for

membership in the Supercartel (see Table 1 for reasons). Some of the related cartels do not compare

to the mostly mechanical-electrical manufactured parts in the current wave. Perhaps the most

comparable predecessor is Auto Glass (a/k/a Carglass), a 2004-2005 cartel that resulted in record EU

fines of $1.76 billion.

54

The current 2000-2014 wave of 80 Auto-Parts cartels is listed in Table 2.

55

50

A popular investigative magazine revealed that EC fines of up to €3 billion (approximately $3.5 billion) are being

considered (Der Spiegel April 7, 2019).

51

Much of the costs of resolving consumer complaints involves repairs for recalled cars and extended repair warranties.

These are not cash compensation, but some OEMs are valuing them at almost equal to cash payments.

52

The Private International Cartels (PIC) data set has unrivaled legal-economic information on more than 900 cartels and

7000 cartelists.

53

Two more were investigated but dropped or cleared by the authorities. In one unique case (Aftermarket Auto Air

Filters), the DOJ was misled by a putative whistle-blower later indicted for lying to investigators. A third alleged cartel

(Automobiles, Canadian imports to US) was dismissed after one company settled.

54

Other possible predecessors are the Indian Tires, Canadian Auto Imports, Auto Manufacturing in Turkey, and FEFC Shipping

cartels are cases in point. Even Automotive Refinishing Paint is not comparable because customers were auto body shops,

not auto OEMs. I hesitantly include the Truck Manufacturing in EU cartel in the Auto-Parts supercartel.

55

Several began before 2000 and a few continued slighted beyond 2012, but all seem to overlap at least in part with the

2000-2012 period.

13

The 80 auto-industry cartels that have formally investigated beginning in 2010 (including the 70

found guilty of cartel conduct) comprise about 6% of the total number of international cartels

detected in the past 30 years (Connor 2019). One possible reason that few auto-parts cartels were

observed in the past is because of the large resources expended on procurement by a relatively small

number of presumably “sophisticated” buyers. Auto manufacturers tend to have procurement

specialists who develop expertise in the supply conditions in the industries from which inputs are

purchased. That is, knowledge about cost conditions was symmetrical. Why that symmetry in

bargaining over prices broke down is yet to be revealed.

Another factor that frequently provokes the formation of cartels is financial stress in the industry.

Of the 70 Auto-Parts cartels with information on their first year of operation, 57 (81%) were

launched during 1999 to 2006. Automotive production worldwide in 1999-2006 was rising from

about 53 million units to 73 million in 2007 (Statistica 2018). Annual production in the United States

in 1999-2007 was in the range of 16 to 18 million units – an historical high for the industry

(Cutchner-Gershenfeld et al. 2015: Figure A).

56

Demand for parts would have risen proportionately.

While there are no reliable, comprehensive profit data for the OEMs, net revenues and gross

margins tend to rise when demand and production rise, so there is little evidence that the OEMs

were financially stressed in 1999-2007. Comparable information about the OEMs’ input suppliers’

financial performance is unavailable, but ought to be hitched to that of their customers.

B. Industry Structure Facilitates Bid-Rigging

At least three-quarters of the Auto-Parts cartels involved rigging the bids of the OEMs (Connor

2019). Except for small numbers of buyers and the vaunted sophistication of their procurement

managers, industry structure and customary practices make many auto-supply industries fertile

ground for overt price fixing. For the products alleged to have been price-rigged, there are few

suppliers in a given geographical production region. For example, the four Japanese suppliers of

Auto Lighting Products control well over 90% of U.S. national supply. Similarly, the top four wiring-

harness suppliers control 77% of the global market (Sedgwick 2013). For 14 cartels, sources indicate

that their median share was 95% (Connor 2019). To some extent, automakers’ policies of running

qualification programs for suppliers created barriers to entry and ultimately contributed to a high

degree of supplier concentration for assembly plants in most markets.

Moreover, “Competitors regularly meet at a variety of events, such as trade fairs or workshops

organized by OEMs, which creates opportunities for illegal discussions” (Bird & Bird 2012). The

auto industry’s labor market has a reputation for being segmented from that of other industries.

Managers and executives of auto suppliers and their clients tend to move jobs by circulating to other

companies in the auto subsector. Legal sharing of technical information between rival suppliers may

morph into sharing of sales transactions, prices, or information on future plans.

However, countervailing these oligopolistic conditions is the fact that automakers are also few in

number and have a reputation for being tough, well informed buyers. Indeed, in the language of

business management, the OEMs are the captains of a complex vertical distribution channel.

57

Auto

56

During the Great Recession, global production fell from the 2007 peak by 15%. During late 2007 to 2010, annual U.S.

production fell to 9.5 to 12.5 million.

57

Far upstream in this subsector are makers of raw materials (iron and bauxite mines, rubber plantations, petroleum

extraction, and the like), commodity materials manufacturers (raw steel and aluminum, rubber, plastic, etc.), and further

14

parts suppliers tend to work closely with the assemblers on product designs because of frequent

model changes. Unlike collusive bid rigging of government tenders, there is nothing in the public

record suggesting ethical lapses by OEM procurement managers. The presumed “sophistication” of

the buyers (the OEMs) should have made collusion unlikely. Moreover, some suppliers – especially

those supplying Japanese brands -- were financially controlled by their buyers.

The auto-assembly industry is the prototypical “global industry.” That is, input-sourcing depends on

distant imports in all markets with significant auto assembly: North America, the EU, Japan, China,

Brazil, South Africa, and others. This commonality in input-supply structures is reinforced by the

tendency of parts suppliers to follow their customers with investments after new assembly facilities

are established. Indeed, there is some anecdotal evidence that Japanese auto companies in the

United States favored their home-country suppliers over even lower-cost U.S.-based suppliers

(Gearino 2015). If true, this conduct raised supplier concentration and contributed to conditions

that facilitated collusion.

The auto parts that were subject to collusion are typically bought through Requests for Proposals

(i.e., “tenders”) issued by the automakers for designs tailored to production of a particular

redesigned vehicle model to begin two to four years hence.

58

These RFPs contain tight quality and

design specifications: size, materials, connections, engineering performance. Buyers provide

expected production numbers for up to six years. The OEMs were satisfied if their auction attracted

two or three bidders, including the incumbent supplier of the component in the vehicle model being

phased out. Buyers convey their expectation that either the component’s quality will be superior to

the current part or that price will be lower (or both). When proposals (a bid) are submitted, designs

and performance standards are highly specified, so virtually the only consideration in choosing the

winner was price. Because the RFPs imposed product homogeneity, this eliminates one potential

factor that tends to frustrate the formation and smooth operation of cartels. In short, colluding over

which bidder would win was made easier. Once a bid was accepted, buyers agreed to stick with the

winner for several years (until a car model was totally redesigned), which prevents entry.

A Surcharge Order of the Japan FTC outlines how two suppliers of windshield wipers organized

one cartel. Mitsuba and Denso agreed to let one of them win an RFP from Fuji Heavy Industries in

June 2000; in September 2002 this pas de deux was repeated for Suzuki; and Nissan was the victim of

a third rigged bid in March 2003 (JFTC 2012: 2).

59

One of the more bizarre episodes was described

by the Japan FTC’s report on the Small Electric Motor Auto Systems cartel. One of the cartelists was

Calsonic Kansei, which is largely owned and controlled Nissan Motors. Calsonic/Nissan rigged high

prices on starters and generators sold only to Fuji Heavy Industries, maker of Subaru cars, and one

manufacturing of materials (sheet steel, aluminum rolls, vulcanized rubber, and plastics with various textures). The auto-

parts cartelists shape and combine these materials into finished components for sale to the OEMs. The channel ends

with final consuming households or businesses.

58

“Bids usually came in for U.S. manufacturers three years before the first model year of a proposed part's typical four-

to six-year production life. The bidding company executives allegedly aligned prices on a model-by-model basis, and

sometimes resorted to code words, meetings at home or remote locations to help keep the conspiracy secret, according

to court records” (BearingCode 8 March 2013) [http://bearingcode.com/newupdates2013.html].

59

This Surcharge Order demonstrates the difficulty of precisely demarcating cartels. The Order identifies cartelization by

seven companies of four non-substitutable parts (generators, starters, wiper systems, and radiator/fan assemblies). The

unifying factor is small electric motors and the presence of Denso Corp. in all four sub-markets. Never did more than

four companies rig bids for a specific part; often it was only two.

15

of the smaller Japanese automakers. Thus, Nissan benefitted strategically in the auto market because

it was able to impose through collusion extra manufacturing costs on a rival’s brand.

It is noteworthy that there is a large array of inputs accounting for the major share of OEM

materials costs that was not subject to collusion. In general, these parts and components are

manufactured through vertical integration by the OEMs themselves: frames, chassis, engine motors

and manifolds, transmissions, and axels are the main examples. These parts were not procured from

independent suppliers by RFPs. A second category of parts are tires, batteries, electronic software,

inputs that can be purchased “off the shelf” when a car is launched and do not require advanced

customization.

C. A Huge Array of Products

Even at this stage, it is hard to know precisely how many markets were affected, their geographic

scope, and whether they were interrelated. This uncertainty arises in part because not all the antitrust

authorities agree on the market definitions involved. The US Government has convicted the largest

number of cartels (48), the EC only 13, and Canada 12. However, after studying the available

information, 70 to 80 markets seem to have been affected in one or more jurisdiction (Table 2).

60

An

illustration from EC prosecutions of a limited list of affected automotive parts is sketched below

(Europost 2019).

60

The list may not be exhaustive. Catalytic converters and electronic navigation & entertainment systems have been

suggested as affected auto-parts products. One source says that the DOJ is investigating 60 cartels. As of June 2019, 48

cartels had been fined by the DOJ, and 22 were penalized by other authorities (including four by U.S. courts).

16

Within some of these cartels, many products are encompassed by integrated parts systems. For

example, such a seemingly well defined product as Wiring Harnesses encompasses many related

products: automotive electrical wiring, lead wire assemblies, cable bond, automotive wiring

connectors, automotive wiring terminals, high voltage wiring, electronic control units, fuse boxes,

relay boxes, and junction blocks. Occupant Safety and Thermal Systems are similar product assemblies.

It is informative to note that no auto inputs that are typically made by the OEMs through direct

backward vertical integration were cartelized. I refer to motors, transmissions, chassis, and steel or

aluminum exterior panels; these are made “in-house” by the leading OEMs, not by independent

suppliers. There are two lessons that can be drawn this pattern. First, when inputs account for a

substantial share of material input costs (say, 5% or so), there is no scope for collusion. Vertical

divestment changes things. Perhaps it is no coincidence that collusion against GM began soon after

it sold its Delco-Remy division in 1994, against Toyota after DENSO no longer supplied a majority

of output to Toyota, etc. Any financial cost savings resulting from divestment may have backfired.

Second, by delegating manufacturing of minor inputs (say, 2% or 3% of total material inputs) to

ostensibly unaffiliated suppliers, the OEMs suffer a substantial loss of information about

manufacturing costs and a consequent loss of bargaining power over price.

61

It is not rational for

buyers to invest large resources in the technologies of procurement when an input – like nuts, bolts,

rivets, and airbags -- is a minor one.

D. Targets of Bid-Rigging

About 17 of the world’s largest, non-Chinese automotive manufacturers (OEMs) were targets of the

input-makers cartel schemes. Typically, two or three suppliers were invited through Requests for

Proposals to submit price quotes for an auto part meant to be compatible with the design for a new

car model that would be produced for three to five years in the future.

The direct auto-parts customers included GM, Ford, and Chrysler/Fiat; Audi/VW, BMW,

Mercedes/Daimler, PSA Peugeot, Renault/Nissan; and Hyundai, Kia, Subaru, Suzuki, Isuzu, Mazda,

Mitsubishi, Toyota, and Honda. In these cartels, pass-on damages were incurred by retailers and

consuming households.

62

In a few cases, a cartel colluded against OEMs after manufacturing was

complete; the Auto Ro-Ro Shipping cartel is one such case; oceanic shipping is an essential service for

large OEMs, because they all export finished vehicles to buyers across the seas. The Ro-Ro Auto

Shipping cartel raised the prices of destination charges on many specific routes with few rivals, such

as Korea-Israel

63

and Europe-Baltimore

64

.

61

I have previously emphasized the increased likelihood of input collusion when the input share is very small. See similar

comments on the Lysine, Citric Acid, and Bulk Vitamins cartels in Connor (2008).

62

In the small number of distributors’ cartels, auto retailers or consumers were directly injured.

63

The origin of Auto Shipping collusion from Korea is a “summit meeting” of nine ro-ro shipping firms in August 26,

2002 in which they agreed to “respect” historical market shares. A separate two-firm cartel began as early as March 2008

on the Israel-Japan route, which was a duopoly from 1993 to 2011 because of the Arab League Boycott of Israel. See

the KFTC Press Release “KFTC imposes sanctions on 10 international cartels of car shipping” dated August 21, 2017

[kftc.go.kr].

64

See Indictment: U.S. v. Anders Boman et al. [https://www.justice.gov/atr/case-document/file/985521/download],

detailing collusion by three employees of Wallensius Wilhelmsen Logistics in the Port of Baltimore 2004-2012.

17

V. Geographic Location Follows Location of Auto Assembly

Price fixing by the Auto Parts cartels occurred in roughly the 50 most industrialized economy of the

world but was concentrated in those nations with important clusters of automotive assembly plants

(i.e., plants operated by the automotive OEMs) (Wikipedia 2019). Collusive meetings among

suppliers generally occurred in the countries where the assembly plants were located, though the

agreements were generally approved by division directors or vice presidents at company

headquarters. If assembly was too small to support in-country or nearby parts manufacturing,

agreements were forged in Japan or other export locations. In the year 2010, based on vehicles

produced in nations that initiated antitrust investigations, shares of world production units were:

North America 13%, Latin America 7.4%, the EU 20.3%, South Africa 1%, and Asia 49%. (Based

on value of sales, the No. American and EU figures might be about 15% and 23%).

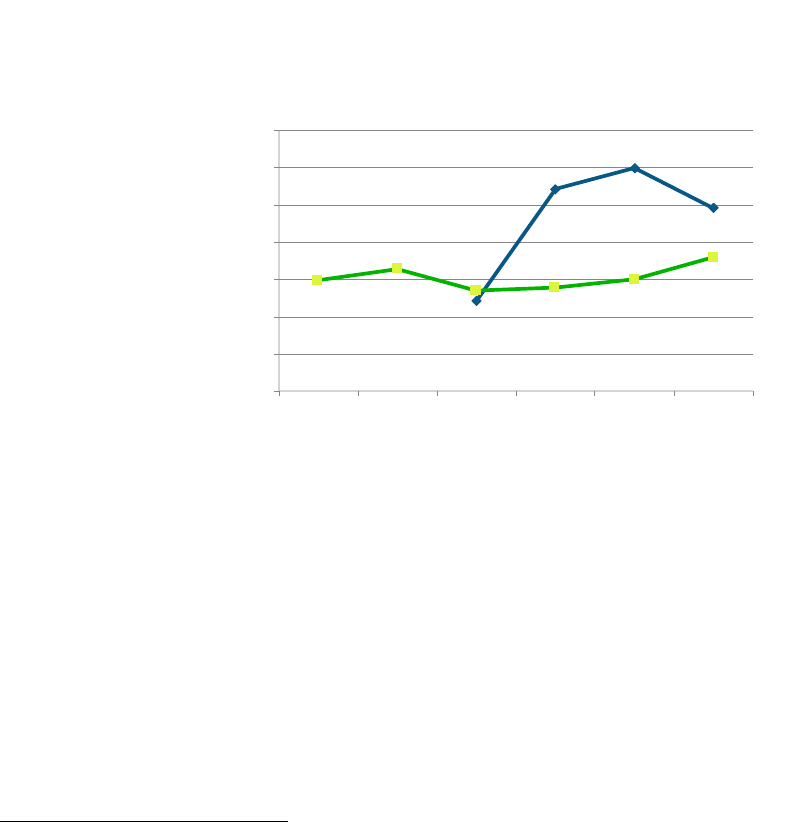

The number of Auto-Parts cartels in major regions detected (investigated) by antitrust authorities is

shown in Figure 1.

The single largest regional location of cartel operations is North America, i.e., Canada and the

United States.

65

North America is closely followed by 26 EU-wide cartels detected by the EC

66

and

nine more localized cases being prosecuted by Member States of the EU. Few, if any, more Auto-

Parts antitrust penalties are likely to emanate from the U.S. DOJ, and Canada’s investigations are

closed. However, the EC may have a couple more future decisions, possibly large-fine automotive

cartels in the pipeline (Niemeyer et al. 2018).

67

65

Canada fined at least one participant in 12 cartels, and the US DOJ fined 48 global cartels; six more cartels are

awaiting penalties from the DOJ or private suits. Both jurisdictions have one large investigation ongoing in early 2019,

the Diesel Motor Emissions case, which is mainly a fraud allegation but may also include price and non-price collusion

violations. See Connor (2017). No investigations have been revealed by Mexican authorities, but the Mexican auto-parts

industry has doubtless been affected by the cartels, because it is closely integrated with U.S. and Canadian production as

a consequence of the NAFTA Agreement.

66

The EC has taken the position that when two or three parts manufacturers colluded on the same parts against two

buyers, then two cartels existed. The DOJ and all other authorities treated this situation as one market and cartel, which

is the definition followed in this paper. The EC has fined only ten cartels as of March 2019, but as many as 23 more may

still be under investigation.

67

These close observers of the EU cartel scene suggest that other “car-related” cartel infringements to be announced

include automotive insurance.

18

1. Auto Parts: Geographic Location of

Collusion, Numbers of Cartels

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

USA &

Canada

EU-Wide EU

Nations

Asia Lat. Am. Africa Global All

March 2019

11

The Rest of the World (ROW) accounts for an additional 34 cartels that did not operate in North

America or in the EU. The Japan and Korea FTCs have brought quite a few Auto-Parts collusion

cases, 21 and 14, respectively. Brazil’s CADE has also been active in cartel enforcement, with 16

cases known to be open and perhaps a few more yet to be announced. Mexico, China, Chile, and

South Africa prosecuted 17 cartel cases.

Finally, the largest category are the 51 global cartels, each of which rigged bids in two or more

continents. Nearly all the global Auto-Parts cartels colluded in at least three continents (North

America, Western Europe, and East Asia), and more than half of the global cartels affected markets

in five or six continents. All of the Auto-Parts of the cartels penalized in the United States are global

cartels. If one were to distribute the affected markets of global cartels to single jurisdictions, except

for North America the number of cartels per region would roughly double in each regional

grouping.

The numbers of detected cartels reflect to some extent the assertiveness of local antitrust authorities.

Bids were rigged for parts sold to OEMs (or their subsidiaries) that have headquarters in the United

States, the EU, Japan, and South Korea. Yet, countries with significant auto assembly activity, such

as South Africa and Australia, have brought relatively few Auto-Parts collusion cases (three and five,

respectively). China has joint ventures involving nearly all of the known targeted OEMs, yet it has so

far indicted only four Auto-Parts cartels.

68

VI. Duration of Collusion

Longer cartel duration generally implies that, ceteris paribus, the amounts of cartel injuries will be

higher. The Auto-Parts cartels endured for above-average lives. The typical international cartel lasts

68

It is likely that the mostly Japanese-owned auto-parts cartelists faced higher levels of competition from Chinese-owned

fringe producers in China than they did in other markets.

19

for a median age of six or seven years. For the 70 Auto-Parts cartels with data, the mean and median

average duration is 109 months (nine years) -- whereas the median average of all other cartels is 60

months (five years) (Figure 2).

69

The reasons for the relative durability of the Auto-Parts cartels can only be a matter of speculation.

Being in the manufacturing sector is one likely explanation. The curious reluctance of most OEMs

to complain to antitrust authorities about bid rigging is another; notably only one OEM (Ford) is

suing for antitrust damages.

2. Median Duration of Auto-Parts vs. All

Other International Cartels

0.0

20.0

40.0

60.0

80.0

100.0

120.0

140.0

Before

1995

1996-2000 2001-05 2006-10 2011-15 2016-18

Months

Year Cartel Discovered

August 2018 284J M Connor, Purdue U.

VII. Antitrust Prosecutions

Nearly all of the Auto-Parts cartels were investigated after leniency applications submitted to U.S,

EU, Canadian, and Japanese antitrust authorities. Today, dozens of antitrust authorities regularly

offer leniency to cartelists.

70

The leniency applicants submit detailed renditions of how a cartel was

organized: the names of corporate and individual participants, their agreements, locations and dates

of meetings, other means of communication, and other direct evidence of the conspiracy that can be

used to prove the guilt of all involved. These proffers were shared with other antitrust authorities to

the extent allowed under cooperation protocols. Evidence of close cooperation is seen in about 20

simultaneous joint raids of suspect cartelists’ headquarters during 2010-2013 by various

69

In the peak discovery period for 60 of the 70 Auto-Parts cartels – 2006 to 2015 – their duration was practically double

the duration of cartels in all other industries, though for eight Auto-Parts cartels discovered after 2015 the two subgroups

did move slightly together. The dip in Auto-Parts duration in the 2001-2005 semi-decade is the result of only two very

early discoveries of atypical automotive cartels.

70

“Part of the investigations seems to be related to what is sometimes referred to as the ‘snowball effect’ of leniency

programs. Companies that are caught in an investigation often carry out a detailed internal audit to determine whether

other business divisions are involved in illegal conduct as well. If this is the case, they typically will file a leniency

application, i.e. they will disclose this conduct voluntarily to the authorities in order to be exempt from fines for

infringements in these other business areas. Under the US ‘Amnesty Plus’ program, there is even a double incentive for

companies to make such a voluntary self-disclosure” (Bird & Bird 2012).

20

combinations of three to seven of the antitrust authorities in the United States, Canada, the EC,

Japan, Korea, Mexico, and Australia.

71

All told, 18 government antitrust authorities indicted cartels

in the Auto-Parts Supercartel.

As a rule, the first leniency applicant to fully cooperate with prosecutors is awarded full immunity

from government penalties, no matter the degree of culpability of the applicant; in other words, the

first to arrive receives amnesty. The PIC data set on Auto-Parts has identified at least 27 amnestied

cartelists, some of them awarded amnesty by multiple jurisdictions (Connor 2019).

72

The most

effective cartel leniency programs are in jurisdictions like the USA and EU that have high fines or

lengthy prison terms. While prosecutors typically extol their effectiveness in uncovering hidden

collusion, leniency programs are sometimes viewed with suspicion in countries where business

cultures and popular sentiment are at odds with competition laws. In Japan, an interview with a high

official of the Ministry of Economy, Industry, and Trade (MEIT, f/k/a MITI) indicated skepticism

of the Auto-Parts antitrust prosecutions and hostility to leniency programs (Greimel 2014). He

objected to the lack of transparency of a process that – contrary to Japanese business culture -- “pits

one company unfairly against another” (ibid.). Furthermore, many authorities then file “copycat

charges” with little additional investigation and “pile on” penalties issued by the first jurisdictions.

73

Of course, Japanese officials committed to inculcating competitive practices hold contrary views.

74

There is a logical problem facing antitrust authorities in applying leniency programs in the Age of

Supercartels. If a group of cartels qualifies as. Genuine supercartel, then under the most such

program rules, only one corporate cartelist can qualify for full amnesty (though many can qualify for

more modest cooperation discounts. But the practical result of such a rigid policy would by far

fewer cartel detections. Moreover, it may take antitrust authorities a year or more to firmly identify

the emergence of a supercartel. Similarly, if in fact a supercartel is a single beast in the shape of

many-headed Hydra, then cartel-based penalties are like lopping off a few heads rather than killing

the body: penalties formulated under a single-cartel concept will be too low because prosecutors use

far too modest estimates of affected commerce.

The first Auto-Parts conviction was announced on January 30, 2012 when Yazaki agreed to plead

guilty to three counts of criminal bid rigging, pay a $470-million fine, and cooperate with the U.S.

DOJ in convicting other cartelists.

75

The Yazaki confession was the first of hundreds of such

admissions This section lays out the outcomes of the global assault of auto-parts bid rigging.

71

To name some: Bearings, Air Flow Meters,

Anti-Vibration Devices, ATF Warmers, Fan Motors, Fuel Injection Systems, Fuel

Senders, Instrument Panel Clusters, Inverters, Motor Generators, Radiators, Starter Motors, Power Steering Assemblies, Variable Valve

Timing Controls, Power Window Motors, Windshield Washer Systems, Windshield Wiper Systems, Wire Harnesses, and Ro-Ro Auto

Shipping.

72

Of which 13 were identified by the EC, four by EU NCAs, and 13 by Japan, Brazil, and China. Ten probable

amnesties emanated from the U.S. DOJ, and there are likely ten more Amnesty-Plus awards.

73

“Piling on” is what lawyers call double jeopardy. However, nearly all antitrust authorities compute fines on the basis of

affected commerce in their jurisdictions, so multiple fines for the same crime are not double jeopardy.

74

Kaori Ito in MEIT’s Competition Enhancement Office noted that headquarters of Japanese companies are committed

to instilling antitrust compliance, but subsidiaries may not have gotten the message (Greimel 2014).

75

The guilty conduct was rigging multiple bids for Wire Harnesses from as early as January 2000 to Feb. 2010 (affected

commerce totaled about $2 billion), for Instrument Panel Clusters from as early as Dec. 2002 to Feb. 2010 ($73 million),

and Fuel Senders from as early as March 2004 to Feb. 2010 ($1.6 million) (DOJ 2012).

21

A. Cartel Penalties

Monetary penalties imposed on companies in each of the 80 Auto-Parts cartels are shown in Table 3.

The total monetary fines and settlements is $20.8 billion (almost $300 million per cartel on average),

which is on its way to equal to Banking (30.4 billion) as a world record amount (Connor 2014). Of

the 80 instances, ten cases have not yet been decided and two involved non-monetary consent

decrees.

As the summary in Figure 3 demonstrates, penalties were mostly announced during the years 2008-

2016. Two-thirds of the known penalties were imposed on cartels that were cracked in 2011-2013

and most of the rest appeared in 2014-2016. Fines in North America and the EU account for 17%

and 58% of total penalties, respectively; fines in the ROW amount to 11%; and private damages paid

account for 14%.

3. Cumulative Auto-Parts Fines,

by Jurisdictions, Up to Feb. 2019

0.0

2.0

4.0

6.0

8.0

10.0

12.0

14.0

16.0

18.0

2005-07 2008-10 2011-13 2014-16 2017-19

Private

ROW

EU NCAs

EC

USA &

Canada

Total $16.3 B

Date First Cartel Participant Penalized

As of early 2019, U.S. and Canadian fining is believed to be complete, but Brazil and some other

ROW agencies will be adding fines for a few years hence. One EC case was decided in early 2019; it

is possible that a small number may yet be announced in 2019-2020.

76

Additionally, several U.S. and

Canadian private damages suits, which often require five or six years to wrap up, are mostly settled.

77

Finally, a small number of European damages actions are in their early stages in 2019. Given these

future decisions, Auto-Parts penalties may approach $25 to $30 billion in a few years. Even if

penalties do rise to $30 billion, Auto-Parts will not surpass the Banking supercartel.

76

EC decision-making is relatively slow. The 132 EC cartel decisions with fines during 1990-2018 took an average of 3.6

years to investigate from the date raids or other press reports reported an investigation underway, and nearly one-fourth

required more than five years. Decisions that ended with cease-and-desist orders only lasted twice as Individual penalties.

77

Based on 243 international cartels, the average time from the date of discovery to the date the first member of a cartel

agreed to settle in a U.S. damages case was 4.0 years.

22

B. Corporate Penalties

At least 473 corporate investigations have been launched worldwide in the Auto-Parts cases as of

early 2019. (The final number discovered is unlikely to exceed 500). Of these, at least 316 corporate

monetary penalties were obtained (plus at least a dozen amnesty awards) by the world’s antitrust

authorities (Table 4). The range in corporate penalties is wide: specifically, 45 penalties (or 14%)

were below $1 million; another 38% of the penalties were “medium size,” i.e., above $1 million but

below $10 million; and one-third of the penalties (157 or 33%) exceeded $10 million, of which 31

were above $100 million and six above $1 billion.

Table 4 groups by ultimate parent owner all of the largest penalties paid by the top 30 offenders.

These 30 corporations and corporate groups paid or have agreed to pay a total of $18.4 billion in

criminal and civil penalties. Although the top firms account for only about 15% of the number of

parent companies, they account for a striking 88% of all the penalties paid by the 300-plus violators.

The greatest Auto-Parts offenders are a mix of famous corporations and more obscure

manufacturers.

78

Perhaps the more unexpected corporate parents in Table 4 are OEMs like Toyota,

Ford and the Renault-Nissan Alliance; they make the list because of their ownership and control of

large auto-parts companies like Toyota’s DENSO, Schaeffer’s Continental Automotive, and

Renault-Nissan’s MELCO.

Some commentators have opined that the large majority of all the Auto-Parts violators are Japanese-

owned companies.

79

While they are indeed by several measures the plurality of the lawbreakers,

Japanese businesses do not form the majority. Looking at the number of companies convicted with

monetary penalties, which total 314, a plurality of 137 (or 44%) of the penalties were placed on

Japanese-owned companies or their local subsidiaries.

80

Four other nations had significant numbers

of violators. Their nationalities are: American (9.9%), German (14.3%), French

81

(9.9%), and Korean

(2.5%). The number of companies from each of the other nations is less than 2%.

Measured by the dollar value of the penalties, the ownership distribution is more diverse (Figure 4).

The lead is still held by Japanese--headquartered companies (41% of dollar penalties). Japanese

firms’ penalties are followed by eight other nationalities: American (16.2%), German (14.7%),

Swedish (4.7%), French (4.2%), Italian (3.6%), Norwegian (3.4%), Indian (1.7%), and Korean

78

Burtis et al. (2018) identified nine of the convicted Auto-Parts companies as unlisted or non-public: Aisan Industry

Co. Ltd., Continental Automotive Electronics LLC, Corning International Kabushiki Kaisha, Hitachi Metals, Ltd.,

Maruyasu Industries Co., Ltd., Omron Automotive Electronics Co. Ltd., Sanden Corp., Toyoda Gosei Co. Ltd., and

Yamada Manufacturing Co., Ltd.

79

Burtis et al. (2018) concluded in late 2018 that of the total of 46 companies that made guilty plea agreements, “ -- the

majority being Japanese component parts manufacturers --” (p. 380).

80

These counts include some double counting of companies, if multiple subsidiaries incurred penalties. Besides the 314