(revised April 2010)

© 2008 SIL International

®

Library of Congress Catalog Number: 2008935395

ISBN: 972-1

555671-255-5

ISSN: 1934-2470

Books published in the SIL e-Books (SILEB) series are intended for scholarly research and

educational use. You may make copies of these publications for research or instructional

purposes free of charge (within fair use guidelines) and without further permission.

Republication or commercial use of SILEB or the documents contained therein is expressly

prohibited without the written consent of the copyright holder(s).

Mary Ruth Wise

Bonnie Brown

Lois Gourley

iv

The Bantu Orthography Manual is a resource for developing writing

systems among the Bantu subgroup of Niger-Congo languages. It oers a

strategy for orthography development, combined with a list of resources

for Bantu linguistic information and the condensed advice of a coterie of

respected Bantu linguistic experts. It oers readability and write-ability

considerations whenever applicable. The Manual has a target audience:

linguists gathering information for orthography development.

Procedures for a “participatory approach” to phonological analysis are

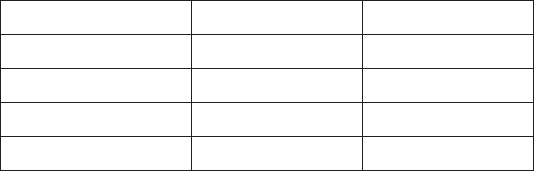

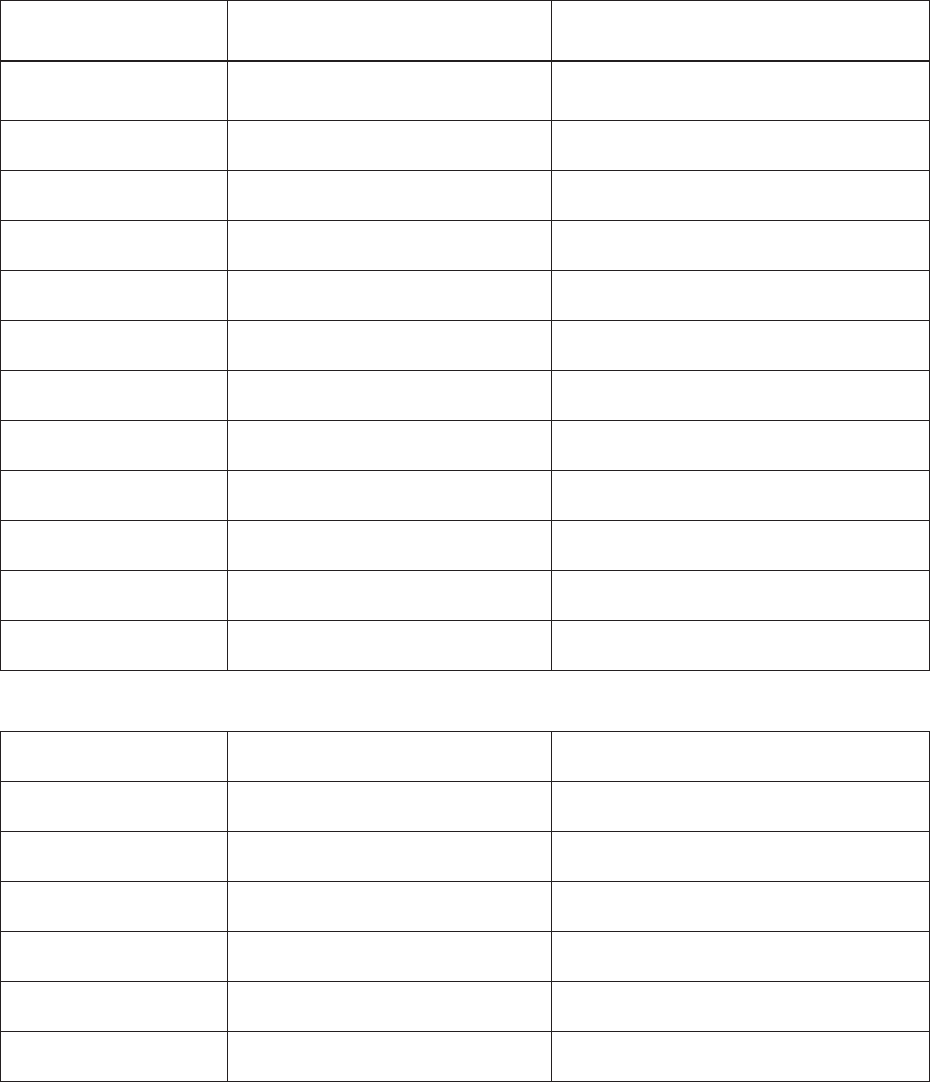

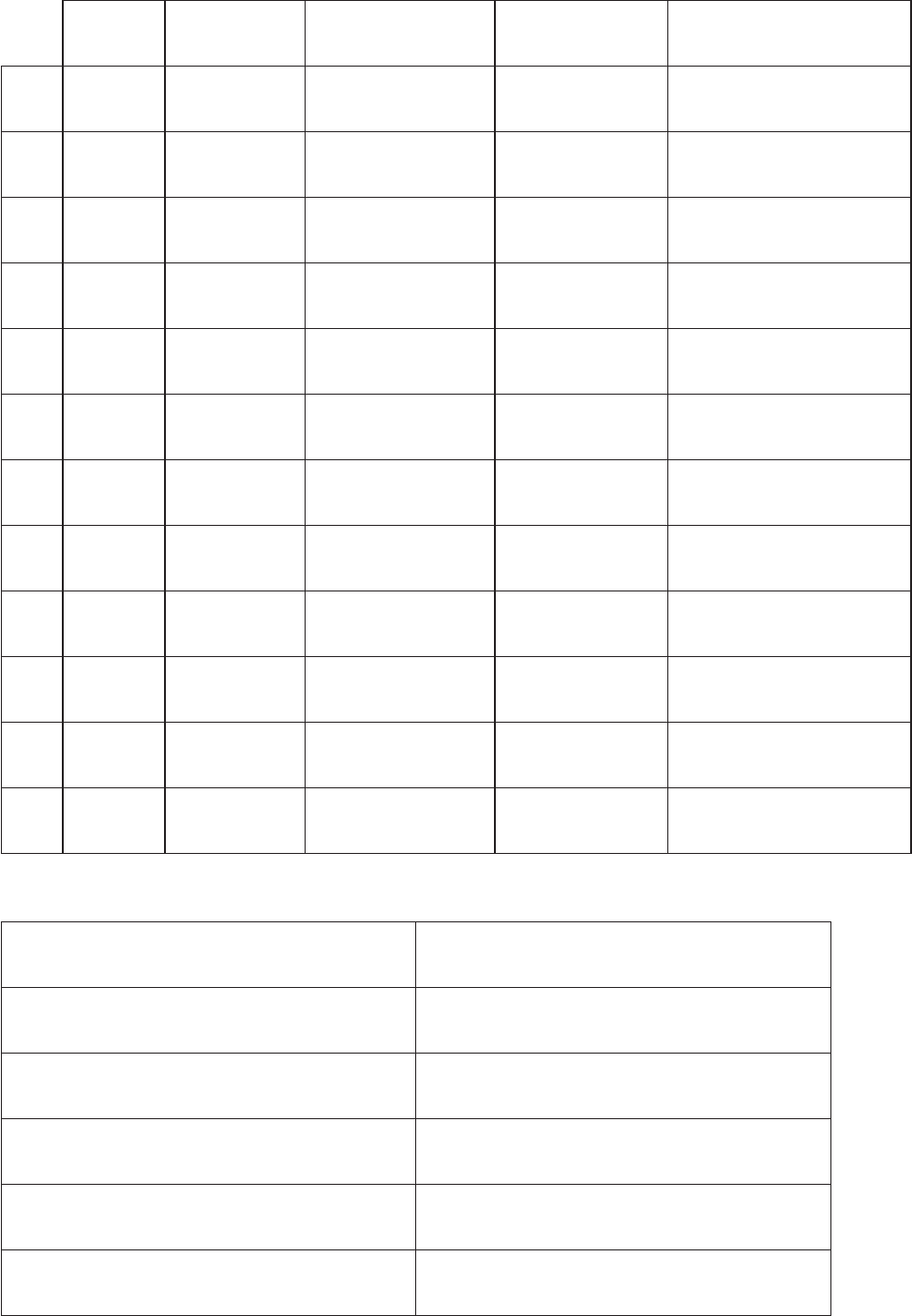

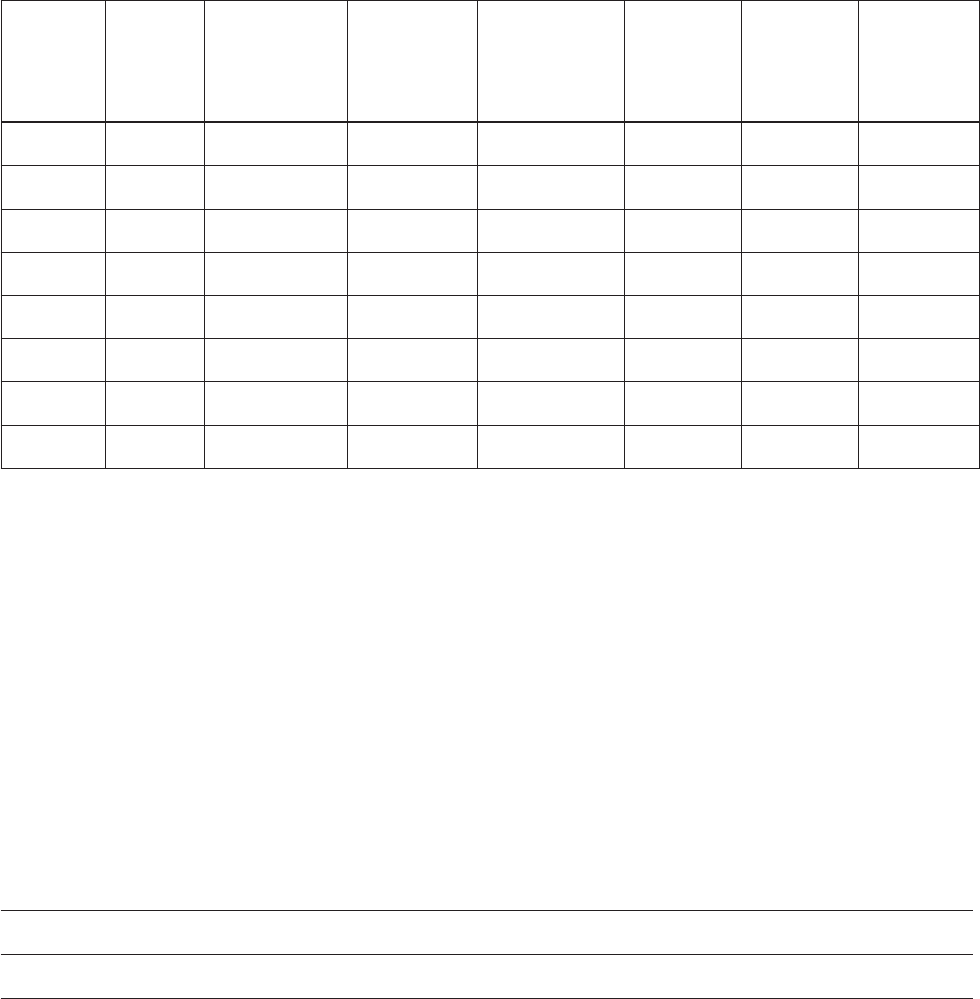

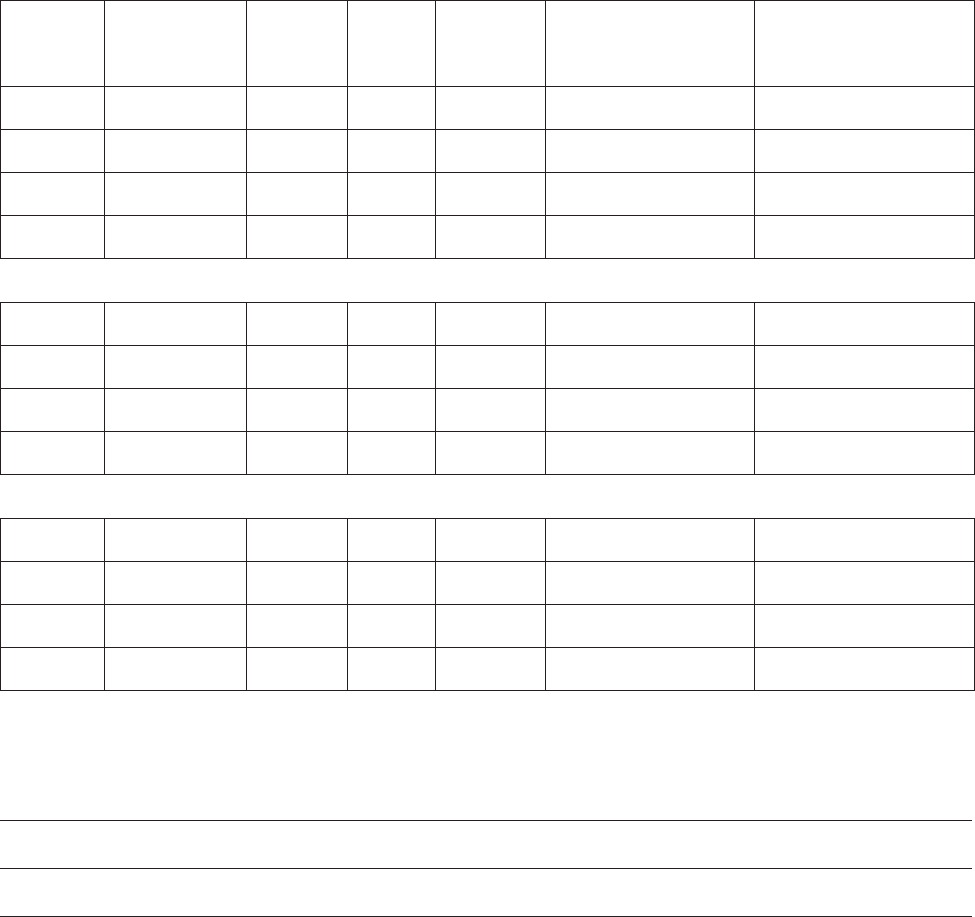

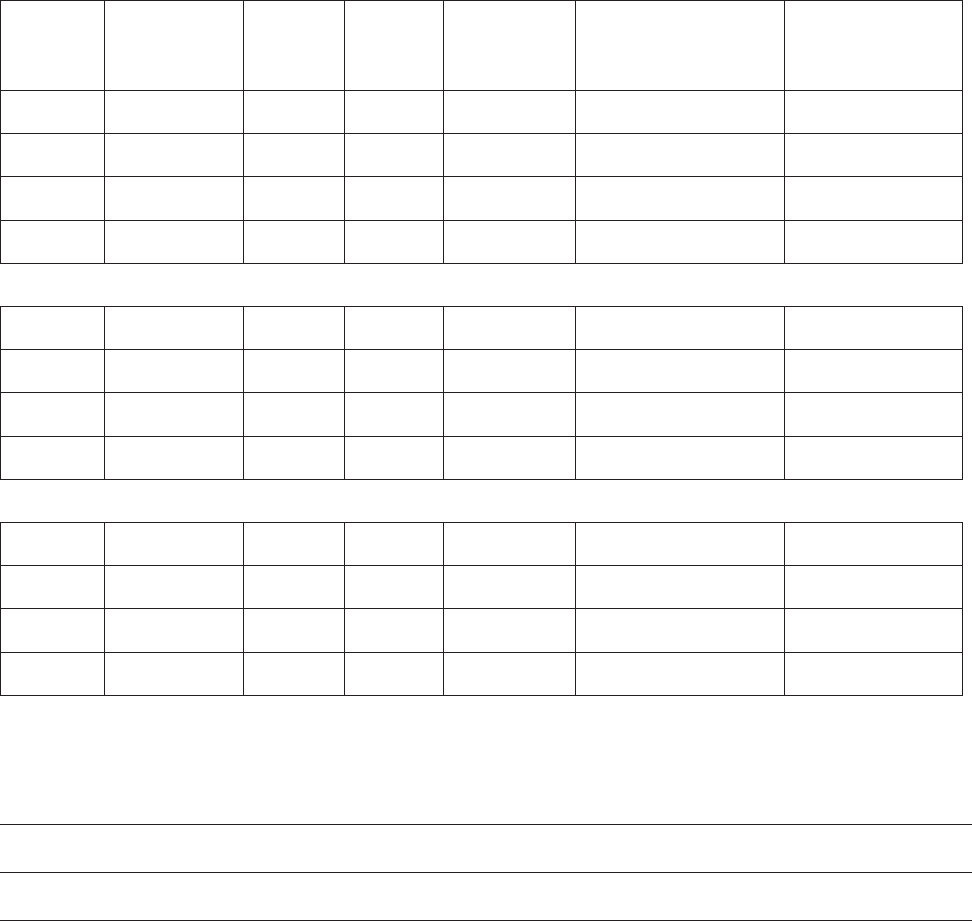

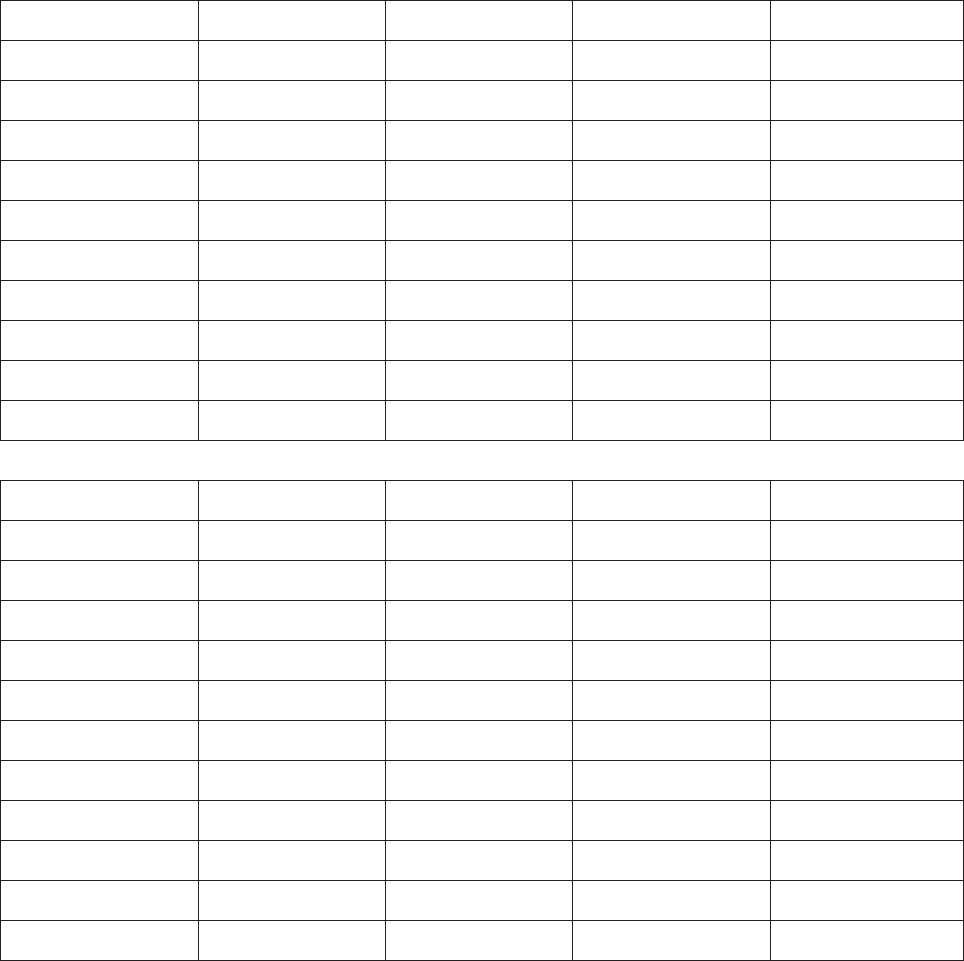

described in one chapter. A series of charts help the linguist document

and organize the phonological and morphological information gathered.

The Linguistic Features chapter lists common linguistic characteristics of

Bantu languages, describes the attendant orthographic challenges, and of-

fers suggested solutions, along with the pedagogical rationale for each.

v

Denition of orthography ......................................................................................................2

The purpose ...........................................................................................................................2

The goal .................................................................................................................................2

Foundational assumptions for orthography development .....................................................2

Elements of the development process ....................................................................................3

Purpose of this manual ..........................................................................................................3

Introduction ...........................................................................................................................4

List of graphemes for the segmental aspects of a Bantu writing system ................................7

Vowels ..............................................................................................................................7

Consonants .......................................................................................................................7

Vowels ..................................................................................................................................10

Vowel systems ................................................................................................................10

Vowel harmony ...............................................................................................................12

Vowel length ..................................................................................................................14

Predictable shortening of an underlyingly long vowel ..................................................21

Semivowels ....................................................................................................................22

Vowel elision (also a word break issue) .........................................................................25

Consonants ..........................................................................................................................26

Liquids ............................................................................................................................26

Fricatives ........................................................................................................................27

Nasals .............................................................................................................................27

Aricates ........................................................................................................................29

Implosives ......................................................................................................................31

Double articulated stops ................................................................................................31

Geminate consonants .....................................................................................................31

Prenasalization ...............................................................................................................32

Labialization and palatalization .....................................................................................33

Velarization ....................................................................................................................36

vi

Morphophonological Processes ...........................................................................................36

Phonological conditioning at morpheme boundaries .....................................................37

Vowel coalescence/assimilation .....................................................................................39

Principles of Tone Marking in an Orthography ...................................................................40

Verbs ..............................................................................................................................42

Nouns .............................................................................................................................43

Functors .........................................................................................................................43

Word Boundary Principles ...................................................................................................43

Clitics vs. axes: two dierent animals .........................................................................45

Augment vowels .............................................................................................................47

Associative marker (wa, ba, gwa, gya, etc.) ...................................................................49

The conjunction na .........................................................................................................51

Vowel elision / coalescence in clitics .............................................................................51

In verbs ...........................................................................................................................52

Generalizations ...............................................................................................................53

Troubleshooting Problem Areas ..........................................................................................54

Probable Test Needs ............................................................................................................54

Who Should Be Tested .........................................................................................................55

Types of Test ........................................................................................................................55

Informal vs. Formal ........................................................................................................55

Giving formal tests .........................................................................................................55

Appendix A: Determining Functional Load for Tone ...........................................................60

Appendix B: Glossary of Linguistic Terminology .................................................................63

Appendix C: Morphological vs. Phonological Rules .............................................................65

vii

The goal ...............................................................................................................................73

Foundational Assumptions for Orthography Development ..................................................73

Goals ....................................................................................................................................73

Linguistic rationale ..............................................................................................................73

Overview ..............................................................................................................................74

Initial Orthography Development: studying phonology and morphophonology... ..........74

Discovery of contrastive sounds ..................................................................................74

Phonotactics: the combinations and combinatory restrictions of

Consonants and Vowels, particularly in root-initial position. .....................................74

Morphology and Morphophonology ...............................................................................74

Approach: Participatory Research ...................................................................................75

Word Collection ...................................................................................................................76

Goals of word collection phase .......................................................................................76

Word collection: wordlists vs. semantic domains ...........................................................76

Roles of Participants .......................................................................................................77

Instructor ........................................................................................................................78

Computer Scribe .............................................................................................................78

Contact person with hosts ...............................................................................................78

Group scribe ....................................................................................................................78

Discussion facilitator .......................................................................................................79

The groups ......................................................................................................................79

Recommended Schedule .................................................................................................79

Elicitation process ...........................................................................................................80

Data Entry ............................................................................................................................81

Computer tools to assist in word collection and card printout .......................................81

Printed word collection forms .........................................................................................81

Keyboarding words .........................................................................................................81

Printing cards ..................................................................................................................82

Other printouts ...............................................................................................................82

Challenges: ..................................................................................................................82

viii

Preparation for Phonological Analysis ............................................................................83

Step 1. Weed out all compound nouns as well as loanwords and phrases ..................83

Step 2. Print out the word cards .................................................................................84

Step 3. Generate a phonology report ..........................................................................84

Workshop use of cards and laptops: an overview ................................................................84

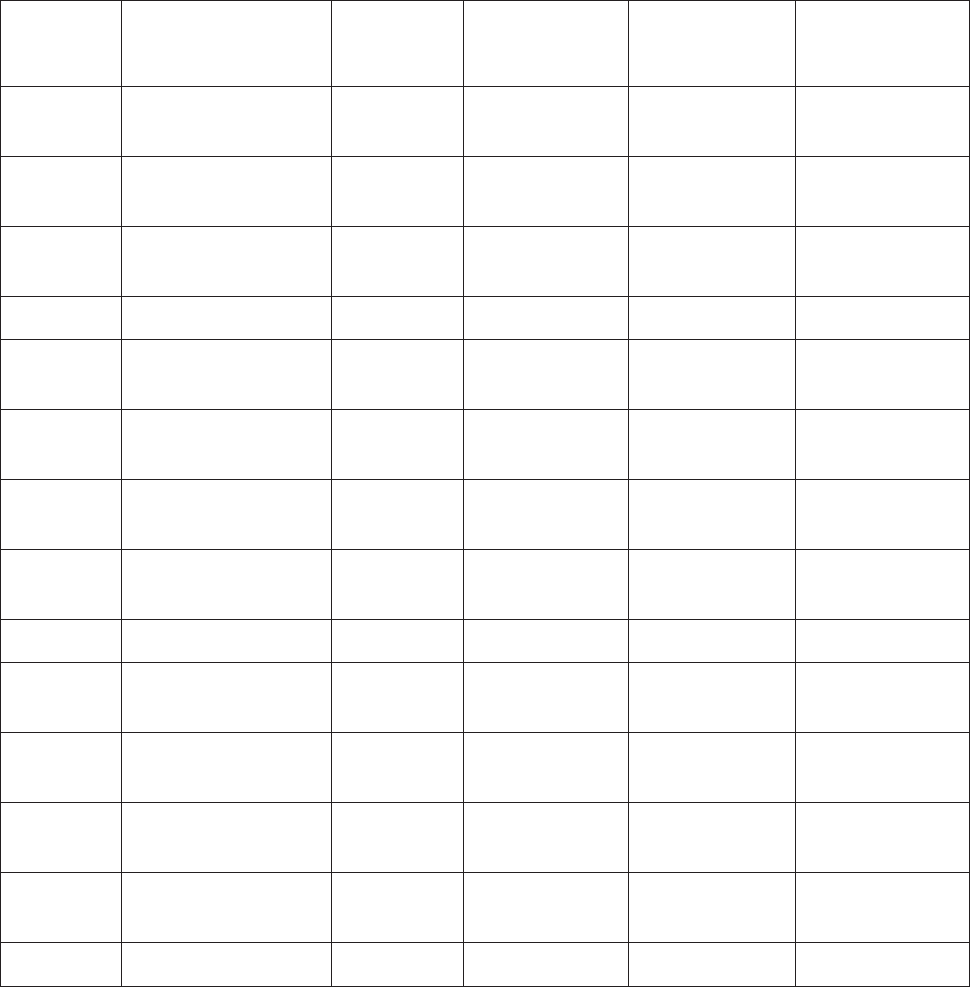

Vowels, Week 1 ....................................................................................................................87

Week 1, Vowels ....................................................................................................................87

Vowels Step 1. Discover lexical roots of nouns with C-initial roots ................................87

Vowels Step 2. Chart distribution of each vowel within nouns,

in which V1 = V2...........................................................................................................88

Vowels Step 3. Study vowel combinations, -CVCV noun roots in which

V1≠V2. .........................................................................................................................88

Vowels Step 4. Discover lexical roots of verbs. Study vowel distribution

in verbs ...........................................................................................................................90

Step 5. Study vowel length .............................................................................................90

Consonants, Week 2 .............................................................................................................91

Consonants Step 1. Look at the CVCV noun roots, sorting by C1 (and V1) ....................91

Consonants Step 2. Sort nouns by C₂ ..............................................................................93

Consonants Step 3. Look for complementary distribution of consonants ........................93

Consonants Step 4. Sort consonants in the CVC verb roots, px–C

1

VC-V .........................94

Consonants Step 5. Sort consonants in the CVC verb roots, px–C

2

VC-V .........................94

Consonants Step 6. Finalize list of consonant phonemes ................................................95

Consonants Step 7. Study and document V-initial roots of nouns and verbs

and vowel harmony (may be done by TA and a few speakers of the

language while others work on Step 9) ...........................................................................95

Consonants Step 8. Identify all noun class prexes (and variants) .................................96

Consonants Step 9. Make alphabet charts .......................................................................97

The Alphabet ........................................................................................................................97

Alphabet Chart Considerations .......................................................................................98

Unresolved alphabet issues ...........................................................................................100

List Revision and Text Collection: Ongoing activities this week and next .........................100

Tone, Week 3 .....................................................................................................................101

Tone Week Step 1. Study tone on verbs ........................................................................101

Tone Week Step 2. Study tone on nouns .......................................................................102

ix

Tone Week Step 3. Record function of tone, nalize wordlists and

alphabet charts..............................................................................................................105

Tone Week Step 4. Edit and review ..............................................................................105

Tone Week Step 5. Close workshop ..............................................................................106

Things to do each time you show someone the wordlist: informal testing of preliminary

orthography (Translate) .....................................................................................................107

Orthography Sketch and Writers’ Guides ...........................................................................109

Nouns, Week 1 ...................................................................................................................110

Step 1. Begin charting adjectives ..................................................................................110

Step 2. Chart noun phrase numerals .............................................................................110

Step 3. Chart demonstrative phrases .............................................................................111

Step 4. Chart demonstrative forms: other .....................................................................111

Step 5. Chart interrogative forms ..................................................................................111

Step 6. Chart pronominal forms-1 .................................................................................111

Step 7. Chart pronominal forms-2 .................................................................................111

Step 8. Chart pronominal forms-3 .................................................................................111

Step 9. Chart diminutives and augmentatives ...............................................................111

Step 10. Chart possessive pronouns ..............................................................................111

Step 11. Locatives .........................................................................................................112

Step 12. Chart associative constructions .......................................................................112

Verbs, Week 2 ....................................................................................................................112

Step 13. Chart Copular Forms .......................................................................................112

Step 14. Chart Copular Forms Part 2 ............................................................................112

Step 15. Chart Morphophonological Processes, Perfective ...........................................112

Step 16. Chart Verbal mood: Imperative Plural ............................................................112

Step 17. Chart Verbal mood: Imperative Singular ........................................................112

Step 18. Chart Verbal mood: Subjunctive .....................................................................113

Step 19. Chart relative phrases, Object Relative and Subject Relative..........................113

Step 20. Chart Use of the Augment on Nouns, continue charting verb forms ...............113

Step 21. Check charts with a linguist ............................................................................113

Verbs and checking of charts, Week 3 ...............................................................................114

Step 21. Print charts .....................................................................................................116

Step 22. Edit stories in groups, referring to the writing rules the group chose during

group charting ..............................................................................................................116

x

Step 23. Closing ceremony and distribution of printed materials .................................116

Appendices

Appendix A: Alphabet Chart Template .........................................................................117

Appendix B: Lesson 1: Goals and products of Workshop 1 ...........................................118

Appendix C: Lesson 2: Helping Readers with our Spelling Decisions............................121

Appendix D: Lesson 3: Consonant Symbol Choices .......................................................125

Appendix E: Lesson 4: Morphemes and Words .............................................................129

Appendix F: Lesson 5: For TAs: Spelling Principles.......................................................131

Appendix G: Lesson 6: Goals and Products of Workshop 2 ...........................................132

Appendix H: Lesson 7: Word Break ...............................................................................137

Appendix I: Lesson 8: Story Editing ..............................................................................141

Appendix J: Noun-Class Prexes for Proto-Bantu .........................................................142

Appendix K: Duruma Noun-Class Morphology..............................................................145

Appendix L: Orthography Workbook Forms .................................................................148

Contents ........................................................................................................................150

1

The Bantu Orthography Manual is not a computer tool but a resource to aid in

orthography decisions. It oers a suggested strategy for orthography development with

a workshop approach, combined with a list of resources for Bantu linguistic information

and the condensed advice of a coterie of respected Bantu linguistic experts: Rod Casali,

Myles Leitch, Oliver Stegen, Constance Kutsch-Lojenga, Ken Olsen, Mike Cahill, Karen Van

Otterloo, and Bill Gardner.* It oers readability and write-ability considerations whenever

applicable, and is written with an informal style to facilitate easy access to information.

Part 1, Bantu Orthography Manual, has a target audience: the Ordinary Working

Linguist (OWL).

1

As such, it does not oer the degree of linguistic detail one can nd in

such extensive, deep and informative collections of Bantu linguistic information as Nurse

and Philippson (2003), though it refers the reader to many such resources.

Part 2, Participatory Approach to Orthography Development provides step-by-step

instructions for carrying out a participatory approach to orthography development, a

concept originated by Constance Kutsch-Lojenga. Its style is less formal and very practical.

The process involves workshops with groups of participants possibly representing several

related Bantu languages.

While the Manual has an academic focus, the Participatory Procedural Guide is less

formal and very practical. It attempts to guide an OWL through a participatory approach

to orthography development. It hyperlinks to the Bantu Orthography Manual, which

should be used often as a reference, as well as a series of eight Literacy Lessons, plus

Proto-Bantu morphology charts and a large Orthography Workbook Form. All are designed

for use during a workshop.

The Linguistic Features chapter of the Manual provides suggestions to help the linguist

and mother-tongue speakers choose symbols to represent the linguistic features of their

languages. It gives an overview of many signicant phonological and morphological

processes as they interact in Bantu languages. Examples of the orthographic challenges are

given and advice is oered as to how these phenomena might best be reected in a writing

system.

2

This chapter can also be used as a complement to the Bantu Phonology Tool, a

computer tool for phonological analysis of Bantu languages.

The principles and suggestions given try to incorporate pedagogical, perceptual, and

sociolinguistic considerations into the decision-making process for graphemic choices. In

this way, it is hoped that the writing system for a given Bantu language will become the

possession, the useful tool, of the mother-tongue speaker.

*

Special thanks go to these contributors: Rod Casali, Constance Kutsch-Lojenga, Bill Gardner, Myles

Leitch, Karen Van Otterloo, Oliver Stegen, Keith Snider, and Helen Eaton.

1

The phenomena described focus on East and Central Africa Bantu languages, with the hope of publishing

a future edition that reects a wider area. Swahili is often referred to as a typical language of wider com-

munication. However, the procedure can be adapted to other parts of the Bantu-speaking world, where other

languages function as the LWC.

2

Native speaker perception and preferences are embedded in our participatory approach to phonological

analysis, which precedes the graphemic decisions, and with orthography testing in local communities

(addressed in other chapters).

2

Consists of two parts:

1. Symbols (in our case, alphabets)

2. Writing rules

• Alphabets require linguistic input from the Bantu dictionary and phonology tools

• Writing rules need these, plus input from Bantu grammar and discourse tools

• Both alphabets and writing rules need input from psycho-linguistic, sociolinguistic,

educational and political realities in the context

• Empowerment of mother-tongue speakers to read and write their languages as a result

of their own informed orthography decisions

• Advancement of academic knowledge and professional skills, both our own and those

of our partners

Develop an orthography for a Bantu language group, in partnership with speakers of that

language (laying a linguistic and educational foundation for the application of that orthog-

raphy to reading and writing)

• Community ownership/involvement in every stage of the orthography development

process, not only to develop orthographies which are accepted by local communities,

but to encourage local understanding of the rationale underlying orthography decisions

• The centrality of linguistic analysis to orthography development, inclusive of

phonology, morphophonemics, grammar and discourse (since these aspects of a spoken

language overlap and inuence one another on the surface, they will seem to compete

with one another for prominence in a writing system)

• Mother-tongue speakers’ perception should play a signicant role in orthography

decisions. That perception can be developed and enriched for those who take part in

the orthography development process

• Orthography-in-use as goal, and also as means for constant feedback and evaluation

• Questions of readability and write-ability will be considered throughout the

development process

3

Chapter 2 - Representing Linguistic Features

• Revisions will be ongoing, and will necessarily reect the political, educational and

social context of the writing system

• The Orthography Development tool is more a concept or a process than a nely tuned

mechanism; i.e., it will not require a computer program

• Templates for the products to be produced while applying the tool/concepts could be

made (i.e., for a Word book, an Alphabet Book, and/or a Writers’ Guide or transition

primer).

• Workshops to produce these and plans for testing followed by application in

communities are the actual tool (or the format/vehicle for implementation)

• Interaction with Ordinary Working Linguists, or OWLs (people who are now developing

and testing their linguistic analyses and applications), to see what challenges they have

encountered in their work and what info (and wisdom) they’ve gained as a result.

A suggested sequence for such an approach is given in Chapter 5, with activities listed

under each objective. The attendance and involvement of local language speakers in each

activity described is assumed; ordinary working linguists and data entry personnel will

also be involved in most of the activities listed.

This orthography manual is not a complete guide for phonological analysis, but is de-

signed for applied linguistics, specically orthography development. It is intended as an

aid toward development of trial orthographies for Bantu languages, using a workshop ap-

proach. It assumes the reader has some familiarity with the grammatical and phonological

characteristics of Bantu languages, and is therefore brief in its descriptions of some Bantu

linguistic phenomena. It contains references, as well as footnotes, and a list of suggested

background reading materials. The last appendix in Part 2 (Appendix L: Orthography

Workbook Form) is a worksheet to be lled in during a series of two workshops.

4

This chapter provides suggestions to help the linguist and mother-tongue speakers

choose symbols to represent the linguistic features of their languages. It gives an over-

view of many signicant processes that occur in Bantu languages and how these phenom-

ena might best be reected in a writing system. We begin with an acknowledgement that

linguistic features are not the only factors in orthography development: “On the surface,

orthography selection and development are linguistic issues; but in practice they are loaded

with imperatives arising from a number of sources” (Eira 1998:171).

Orthographies are complex visual representations of language and thought which are

designed to facilitate literate communication. Because of the intertwining of phonology,

morphology, and several cognitive processes in the decoding of print, sociolinguistic, and

pedagogical considerations for orthography decisions will be presented in this chapter,

though it is organized around linguistic features of Bantu languages. Just representing

sounds with graphemes is not enough. Language is more than sound, and reading and

writing are more than recognition and transcription of sounds alone. A good orthography

enables readers to quickly recognize meaning, and its spelling rules are as simple as pos-

sible, to aid the writer.

Solid linguistic analysis, while not the only factor in orthography decisions,

1

is essential

to the development of a good orthography. It under-girds any writing system which ac-

curately represents the speech and perception of the mother-tongue speaker. Toward that

same end, the following principles and suggestions try to incorporate pedagogical, per-

ceptual, and sociolinguistic considerations into the decision-making process for graphemic

choices. In this way, it is hoped that the writing system for a given Bantu language will

truly become the possession, the useful tool, of the mother-tongue speaker.

William Smalley’s ve criteria for orthography decisions (1964:34) are still widely used

today, though he had transfer from mother-tongue to the language of wider communica-

tion (LWC) in mind. In Africa today, our situation is often the reverse, with mother-tongue

literacy coming later. His criteria with my annotations are:

1. Maximum motivation for the learner (Smalley refers to issues of ethnic and

national identity)

2. Maximum representation of speech (phonemic writing, with some exceptions

where morphology aects phonology, and vice versa)

3. Maximum ease of learning (simplicity of rules)

4. Maximum transfer [to/from] literacy in a LWC, and

5. Maximum ease of reproduction (for publication purposes)

1 “

A better use of linguistics is as a source of insights about orthography options, and as a tool to probe the

orthographic insights of native speakers” (Bird 2000:29).

5

Chapter 2 - Representing Linguistic Features

One further point could be added:

6. Maximum recognition/transmission of meaning.

Smalley alludes to preservation of morphemes in his second point. Bantu languag-

es, though, are particularly capable of packing multiple morphemes within one word.

Phonological processes alter the surface structure of those adjoining morphemes signi-

cantly. Since consistency of morpheme shape facilitates spelling, reading uency, and

comprehension of written text, a Bantu writing system’s ability to help the reader recognize

morphemes merits focused attention.

This orthography manual is not a guide for phonological analysis, but for applied linguis-

tics, specically orthography development. It is necessarily specic in its focus; it is not a

substitute for general knowledge of orthography principles. I advocate familiarity with Bird

(1998), Gardner (2001, 2005), Kutsch-Lojenga (1993), Smalley (1964), Snider (1998, 2005),

and Ssemakula (2005). These sources will give you some generalizations about the phono-

logical processes and morphological structures of Bantu languages or explain basic orthog-

raphy principles not detailed in this manual. A course on orthography principles is also

oered in the summers at the University of North Dakota.

A word about shallow versus deep orthographies is necessary here. There is a continuum

between deep, meaning-based writing systems in which the primary units of meaning

represent morphemes (such as Mandarin), and more shallow, alphabetic writing systems

which are based on phonemes, such as Italian, Serbo-Croatian, and Luganda. Deep orthog-

raphies represent the morphology of the language more than they do the phonology, while

shallow orthographies aim to closely represent the phonology of the language. Even within

alphabetic writing systems a variety of depth exists, between the more morpheme-preserv-

ing orthographies such as English and French and the more phoneme-based orthographies

of Swahili and Lugungu.

An ideal orthography matches the language it represents

. “Shallow orthographies are

characteristic of languages in which morphemic relatives have consistent pronunciations”

(Mattingly 1992:150). At the opposite end of the spectrum are languages which require a

deep orthography. They have morphemes which are subject to a lot of phonological varia-

tion and/or many homophones which must be distinguished in writing.

There is a tension between the strengths of each kind of orthography. The shallowest

orthography gives the new reader/writer lots of control. With recognition of a handful

of symbols he/she can recognize and spell anything they can speak or say, based upon a

one-to-one correspondence between sound and symbol. But no writing system is actually

capable of completely representing speech. Both readers and writers are assisted by writ-

ing according to word-level phonology, rather than phrase-level phonology. Moving towards

a deep orthography allows homophones to be distinguished while words whose pronun-

ciation varies in context (the dog vs. the apple) can be given a xed representation. This

allows the experienced reader to access meaning rapidly. The issue of morphology and its

eect upon the phonology of a language (morphophonological alternation) will arise very

frequently in the process of orthography development for a Bantu language.

Orthographies should usually be developed with the mature reader in mind. Therefore,

preserve morphemes when possible, especially if a surface-level representation seems to be

6

Bantu Orthography Manual

in equal competition with a morpheme for graphemic representation. Think beyond the in-

dividual segment. Think of a whole word. Lexical changes which take place within a word

are usually written. (For more explanation, see Part 1, Appendix D.)

2

Lugungu, for example,

has a rule that changes the phoneme /r/ into the phoneme /d/ when a morpheme ending

in /n/ is prexed. That morphophonemic change, /kuruga/>/nduga/ when the prex /n/

is added, takes place within the boundaries of a word and should be written.

When it’s possible (sociolinguistically) to avoid digraphs, do so—but you must consider

the transferability of your symbols to the LWC (language of wider communication) in your

area. If the LWC is Swahili, your spelling options are rather narrow.

Spell the way people speak in slow speech, rather than rapid conversation. Elision of seg-

ments dropped in rapid speech is not recommended for several reasons:

1. If a phoneme or a morpheme is written fully, people can recognize meaning

quickly. For example, the Bantu associative marker is /Ca/ or /CCa/. The initial

consonant of this word changes depending upon the class of the noun it modies,

leaving only the word-nal /a/ to give it consistency of appearance. In rapid

speech, this one vowel is often elided and replaced, if the noun it precedes

is vowel-initial. For example, in Ikizu (E402J), the associative marker has an

underlying <> as its vowel, but because it is pronounced together with the

following word, in rapid speech the <> coalesces with a vowel-initial augment

and elides. The associative, a word in its own right, is written with the vowel

that would ordinarily be the augment of the following noun. Visually, then,

recognition of the associative marker is completely lost to the reader whenever it

precedes a vowel-initial noun.

2. If a phoneme is written fully, ambiguity is kept at a minimum. For example, if

a certain vowel is elided in rapid speech, if it is not represented in writing, the

reader may be unsure which vowel is missing.

3. The apostrophe, generally the symbol of choice for indicating elision, is used in

the standard Swahili alphabet as a part of the trigraph <>. When the LWC

includes this trigraph, mother-tongue reading uency is slowed and accuracy of

spelling may be hindered if the apostrophe is further used to indicate elision or

phonological attachment of clitics. Apostrophes have several uses in many Bantu

orthographies, sometimes indicating a glottal stop (in Cameroon), the attachment

of clitics to larger words, the deletion of a vowel across word boundaries, or as

part of the consonant digraph <>. This multi-purpose usage of <> slows

uency of reading and hinders accuracy of spelling. Avoid such multiple uses of a

symbol.

At times (rarely) for sociolinguistic reasons, an orthography may have to represent a pho-

netic sound [ ], rather than just representing the contrastive phonemes / /, of a language.

For example, a language group may insist upon writing a distinction between [l] and [ɾ] for

purposes of reading transfer to a LWC, even though they may not be contrastive phonemes

for their language group. The symbols for sounds are enclosed in [ ] and the graphemes

in < >.

2

This principle takes on great importance when spelling and word break decisions are made, for associa-

tive markers in particular (also see section on word breaks).

7

Chapter 2 - Representing Linguistic Features

The best grapheme options are listed rst; less desirable ones follow them. The format for

each grapheme suggestion will be like this one:

ɑ:] Options: <>

1. Vowel Systems

2. Five-vowel systems: <>

3. Seven-vowel systems: <> or <>

4. Vowel Length: <>

5. Semivowels: <> and <>

6. Vowel elision: see Vowel elision

1. Liquids

[l] Options: <> or<>

[ɾ] Options: <> or <>

2. Fricatives

[ð] Options: <> or <>

[Ɵ] Options: <>

[ɤ] Options: <> or <>

[ß] Options: <> or <> or <>

This list is not exhaustive

3. Nasals

Velar Nasal

[ŋ] Options: <> (or <>or <> or <>

Palatal nasal [ɲ] (see “Labialization and palatalization” below)

Homorganic nasalization

4. Aricates

[tʃ] Options: <> (or <> or <> or <>)

[ts] Options: <> or <>(less desirable Francophone)

8

Bantu Orthography Manual

[dz] Options:<>

[dƷ] Options: <> (Swahili inuence) or <> (French inuence)

[ʒ] Options: <> or <>

5. Implosives

[ɓ] Options: <> or <> or <> (or <> or <>)

[ɗ] Options: <> or <> or <> (or <> or <>)

6. Double articulated stops (Labialized velars)

[k͡p] Options: <> or rarely <>

[g͡b] Options: <> or rarely <>

7. Geminate consonants

8. Prenasalization - Prenasalized labiodental fricatives

[

ͫ

f] Options: <> or, less optimally, <>

[

ͫ

v] Options: <> or, less optimally, <>

9. Prenasalization - Prenasalized palatals

[͡tʃ] Options: <>

[͡dʒ] Options: <>

10. Prenasalization: Prenasalized velars

[

n

k] Options: <> or <>

[

n

g] Options: <> or <>

11. Prenasalization: Prenasalized double articulated stops

[

n m

͡kp] Options: <>

[

n m

͡gb] Options: <>

12. Labialization and palatalization - Labialized consonants

[tʷ] Options: <> or <>

13. Labialization and palatalization – Palatalized consonants

[tʲ] Options:<> or <>

14. Labialization and palatalization - Palatal nasal

[ɲ] Options: <> or <> or <>

15. Palatal nasal contrasting with palatalized alveolar nasal [nʲ] and palatalized palatal

nasal [ɲʲ]

[ɲ] Options: <> or <> or <>

9

Chapter 2 - Representing Linguistic Features

[nʲ] Options: <> or <>

[ɲʲ] Options: <> or <>

Labialized and palatalized consonants contrasting with CSV sequences

[kʷe] Options: <> or <>

[kuwe]Options: <> or <> or <>

[pʲa] Options: <> or <>

[pija] Options: <> or <>, <> or <>

16. Velarization: see Velarization

10

Bantu Orthography Manual

Since there are only ve vowel letters in the Roman alphabet, we are left with the option

of altering these currently existing letters to multiply the grapheme options.

Bantu orthographies most commonly have added ~ or ^ over a vowel to distinguish it

from a similar grapheme, or put a line directly through it, as in <>. Underlining and,

rarely, the placing of a dot under a vowel have also been used. These latter two options

make letter/sound recognition slower, but with nine-vowel systems the need for contrastive

representation requires ingenuity. The ability to type the characters is important for litera-

cy, but several Unicode-compatible options are now available.

Bantu phonology is highly sensitive to morphological considerations. Underlying vowel

distribution within specic morphological slots is highly restricted, both in seven-vowel

and ve-vowel languages. Not only are vowels limited as to their distribution within a

word, but there are rules which restrict their occurrence in sequence, especially within

stems (Hyman 2003:46).

3

Typically, there are more contrastive vowels stem-initially than in

the rest of a Bantu word.

The standard ve Roman alphabet letters are used for these systems, representing the

vowels closest to those of the LWC in the perception of mother-tongue speakers.

Swahili’s ve-vowel

system is shown

below (Maddieson:16)

i ninety

ɛ be late

a rst

ɔ hippo

u porridge

i/І u

e/ɛ o/ɔ

a

Two kinds of seven-vowel systems are typical, with contrast for advanced tongue root

(for simplicity’s sake, we are considering +/-ATR distinction as equivalent to tense/lax).

3

For an example, see Figure 1, Tharaka Vowel Coalescence.

11

Chapter 2 - Representing Linguistic Features

ɩ ʋ

e o

ɛ ɔ

ɑ

ɩ u

I ʊ

ɛ ɔ

ɑ

Rangi (F33), Nyakyusa (M31), Nande (DJ42), and Vwanji (G66) are examples of the

upper type seven vowel system. Oliver Stegen (pc) provided the following examples from

Rangi.

ɩ mushroom

ɪ spider

ɛ abdomen

ɑ drizzle

ɔ fallow eld

ʊ mosquito

u strength

A word about the distribution of vowels in seven-vowel systems may be helpful.

Axes often contain a smaller vowel inventory, most typically ve vowels. They may ex-

hibit phonetic variants with the ve phonemes, though, if they harmonize with the vowels

in the roots. The vowels in the augment and prex actually can help prepare the reader to

recognize the root.

Word-nally, even roots of words may have a smaller vowel inventory. There is often

even devoicing of these word-nal vowels.

Bila (D32), like Budu (D332) and some others in northeastern DRC, has a nine-vowel sys-

tem with ATR-based vowel harmony (Kutsch-Lojenga 2003:450-474). A nine-vowel system

will have to distinctively represent the vowels /ɛ/ and /ɔ/.

12

Bantu Orthography Manual

i u

ɪ ʊ

e o

ɛ ɑ ɔ

Vowel harmony is a common phenomenon in which a vowel or vowels harmonize in

some quality with other vowels in a word. It can be seen as the spreading of a phonetic

feature (back, high, round, advanced tongue root) within a word. The spread is usually

leftward from the root, or leftward from a derivational extension. The vowels of one group

tend to occur with each other in words, to the exclusion of vowels of the other group. The

phoneme /a/, however, is usually a member of both groups in Bantu languages, so it is not

aected.

Vowel height harmony is very common, and usually aects only the vowels of derivation-

al suxes such as the causative, applicative, reversive/separative, neuter, and combinations

of these.

ATR harmony, on the other hand,.occurs only in Bantu languages with seven or more

vowels. The vowels are divided into two mutually exclusive groups, one known as +ATR

vowels, and the other as -ATR. As stated earlier, the vowel /a/occurs with both groups. It

often blocks the spreading of the harmony in a given language.

In a language with ATR harmony, all roots (noun roots, verb roots and others) will con-

tain only vowels of one group or the other, but not both. The “dominant” value of ATR

(usually +ATR in narrow Bantu) is the one that causes the other value to change to be like

it. In a system where +ATR is dominant, a -ATR vowel can change to become +ATR, but a

+ATR vowel will never change to become -ATR.

In most Bantu languages, the +ATR feature spreads leftward from a triggering vowel.

This may be a root vowel aecting a prex as in (2), or a sux vowel causing a change in

the vowels to its left. This means that even the vowels in the root can be aected.

Vowel height harmony is shown in (1) with altered vowels in bold, and ATR (advanced

tongue root) harmony as reported for many Bantu languages such as Rangi (F30), in (2)

from Stegen (pc), and Malila (3) from Helen Eaton (pc) and Constance Kutsch-Lojenga. The

Rangi example shows that the –ATR nominal prex is changed to +ATR when it occurs

with a +ATR root.

(1) Swahili:

-imba ‘sing’ + applicative >

-kata ‘cut’ + applicative >

-vuta ‘pull’ + applicative >

-leta ‘bring’ + applicative >

-soma ‘read’ + applicative >

13

Chapter 2 - Representing Linguistic Features

(2) Rangi:

mʊ- work mʊrɪmɔ

snake sp. mʊlalɔ

mouth mʊlɔmɔ

God mʊlʊgʊ

mu- slope mugiritʰɔ

whistle muluri

Kutsch-Lojenga says of Malila (M20), “The [+high] initial vowel of the -ile sux is [+ATR]

and changes all other vowels of the verb word to its left into [+ATR], however many /a/-

vowels are found in between. This means changes in the verb-root vowel from /ɪ/ to /i/

and from /ʊ/ to /u/ as well as the the allophonic realisations [e] and [o] of underlying /ɛ/

and /ɔ/.” The allophonic dierences between e /ɛ and o/ɔ are not written (note that the /a/

is not aected by the harmony process).

(3) Malila

kʉmʉpɨmba ‘to carry him’

amupimbile ‘he has carried him’

kʉmʉbhʉʉzya ‘to tell him’

amubhuziizye ‘he has told him’

Mother-tongue speakers are aware of the changes from one vowel phoneme to another, in

these examples. This means the changes should be represented in the orthography. Some

changes are only allophonic, and these are not written. In both ATR languages exemplied

above, when a +ATR vowel follows underlying –ATR mid vowels /ɛ/ and /ɔ/, these mid

vowels are pronounced as [e] and [o]. These distinctions, only discerned by the phoneti-

cian, are of course not written.

Write word-internal changes which the native speaker is aware of, even if this means a

given morpheme, such as a noun class prex or even a verbal root, may have two written

forms .

4

That would mean that word-internal phonemic (not phonetic) changes due to vowel

harmony rules should be written. This rule will make spelling intuitive for the writer.

The reader is already accustomed to the morphophonologically conditioned alternations in

speech, so will learn to access meaning despite the resulting altered appearance of some

morphemes. The reader is often actually assisted by this surface-level representation of

vowel harmony, because it usually moves leftward from the root. The reader, beginning

at the left end of a word and moving to the right, nds a lot of predictability of the form

the root will take, based upon the rst vowel he/she sees. Indicating the vowel harmony

4

A rare result of vowel harmony which alters a vowel in the root is ambiguity between two roots, but the

context usually clears it up for the reader and the writer is helped immeasureably by writing what he/she

actually hears.

14

Bantu Orthography Manual

changes also means that the reader does not have to read the entire word before he can

pronounce its beginning correctly.

The following section oers suggestions for orthographic representation of the vowels of

a given language.

1. In choosing graphemes for each of the vowels, decision-makers must rst consider

which of them are most closely associated with those of the LWC. These will

probably be given commonly used vowel symbols. The remainder then will

probably require diacritics to distinguish them. Possible diacritic modications

to a vowel symbol are: <←><>, and <>. In writing systems which

represent tone above any syllable, the rst option, <←>, is preferable to

facilitate recognition of both the vowel symbol and its tone. The Tharaka use of a

circumex (<>, <>) above two of its vowels would be inappropriate if tone

were written over any of its vowels (it is not).

2. If the orthographies of surrounding languages use certain diacritics for vowels,

this may aect your choice of symbols, especially if many people have learned to

read using that system.

5

3. For consistency, always use diacritics with the same + or – ATR attributes,

because the contrast will be a natural one for the mother-tongue speaker. For

example, do not use a diacritic on a [-ATR] front vowel, while also using it on a

[+ATR] back vowel.

4. One suggestion, all other things being equal (i.e., never violate rule 3), is to add

the diacritics to the least frequently occurring vowels. This facilitates speed for

typists and writers, since the symbol won’t have to be written as often. It may also

facilitate speed of symbol recognition for readers.

The suggested vowel graphemes are shown below, and they avoid diacritics above the

letter.

V Options

5V orthography: < >

7V orthography: either < > or < >

9V orthography: < >

Some Bantu languages have phonemic vowel length, while others do not.

Hyman (2003:42) lists ve [potential] sources of vowel length in Bantu:

5

This assumes that the number of vowels in these nearby languages is equal to the number in the

language in question. Underdierentiation of vowels for a language should be avoided at all costs!

15

Chapter 2 - Representing Linguistic Features

1. Phonemic length

2. Concatenation (either across morpheme boundaries or through consonant elision)

3. Gliding plus compensatory lengthening

4. Compensatory lengthening preceding a moraic nasal plus consonant

5. Penultimate vowel lengthening

This chapter addresses point 1 under “Phonemically long vowels.” It addresses points 2,

3, 4, and 5 briey, under “Conditioned long vowels.”

Rod Casali identies two more sources of vowel length.

1. elision of one of two adjacent nonidentical vowels, with compensatory

lengthening of the remaining vowel (for an example, see the Tharaka vowel

coalescence chart, gure1

2. phonetic lengthening of underlying short vowels that bear surface contour tone

In regard to this last point, it should also be noted that a long vowel (either phonemi-

cally long or one in which length phonologically conditioned or attributable to morphologi-

cal concatenation) may be longer, or at least perceived as longer, when it is realized with a

contour tone (falling or rising) rather than when it has a level tone.

Some Bantu languages have phonemic vowel length, while others do not.

Proto-Bantu has been reconstructed as having seven vowels /į,

6

i, e, a, o, u, ų/ plus

phonemic length (Hyman 2003:42). Many, but by no means all, Bantu languages have re-

tained phonemic length in their vowel systems. It is easy to determine whether a language

has phonemically long vowels by sorting bisyllabic (CVCV) noun and verb stems using the

participatory approach to language analysis. If there is phonemic vowel length, these stems

will fall into two sets: CVCV and CVVCV. Noun stems containing consonant-glide sequences

(Cy or Cw) or nasal-consonant sequences (NC), e.g., mb, nd, ng, are not used in this initial

sorting for phonemic length. They will be used in the sorting for conditioned vowel length.

If the sorting of the stems with glides and prenasalized consonants also results in two sets,

there is no orthographically signicant conditioning for vowel lengthening, and all long

vowels must be marked as such.

If a language has phonemically long vowels, they must be marked in the orthography

as long. The orthographic representation of phonemic vowel length is doubly important in

languages where the marking of phonemic tone is done sparingly, because the fewer phone-

mic cues the reader has, the harder it will be for the reader to determine the meaning of a

given word.

Most Bantu orthographies denote long vowels by doubling the vowel symbol. The use of

two identical vowel symbols seems to match Bantu speakers’ perception of vowel length:

<>, <>, <>, <>, <>.

6

The vowels į and ų constitute extra-high vowels. The subscript diacritic is a convention peculiar to Proto-

Bantu vowels.

16

Bantu Orthography Manual

People do not generally object to the writing of double vowels once they realize that

vowel length is an important contrast in their language. The use of double vowels will be

unfamiliar even to most literate people, however, and at rst may make it harder for people

to spell their language correctly.

7

Thus, spelling rules must be taught and practiced once

the orthography is introduced. With time, readers and writers will realize the usefulness

of long vowels in distinguishing words whose contrast would be otherwise ignored by the

writing system.

In many of the Bantu languages with contrastive (phonemic) vowel length, one also nds

noncontrastive (phonologically conditioned) vowel length.

Conditioned vowel length is usually found in these environments:

• before a prenasalized consonant

• following a labialized or palatalized consonant (Cy or Cw) or a semivowel (y or w)8

If a language has phonologically conditioned length, as a great number of Bantu languag-

es do,

9

speakers will signicantly lengthen any vowel in the two environments mentioned

above. Speakers will not be able to distinguish a short vowel from a long vowel in these

environments. They will all sound the same length to them. Thus, there will be no vowel

length contrast possible in this environment.

10

Whether the vowels in these conditioning

environments should be written as short or long in the orthography depends on a number

of factors and is best determined by testing the perceptions and preferences of both readers

and writers.

Depending on the language, the actual phonetic duration of such conditioned long vowels

may be nearly the same as a phonemically long vowel, or it may be something in between.

Ganda (JE15) and Sukuma (F21) both have phonemic length and conditioned length.

However, the conditioned long vowels in Ganda are much closer in duration to underly-

ing long vowels in Ganda than they are in Sukuma. Sukuma lengthened vowels are almost

exactly intermediate between underlying long and short vowels (Maddieson 2003:37).

In some languages, perhaps like Sukuma, speakers may feel that the vowels in the

length-conditioning environments group with short vowels, rather than long. If this is the

case, the obvious choice is to use a single vowel to write the phonologically conditioned

long vowels, since it matches the speakers’ perception, and they will automatically ap-

ply the correct degree of phonetic lengthening to vowels which occur in the conditioning

environments.

An example of a language where conditioned vowels are not quite as long as phonemi-

cally long vowels is Tharaka. However, whenever a vowel precedes a prenasalized stop, the

vowel still sounds long to a mother-tongue speaker. Thus, actual phonetic length of these

7

During literacy lectures at the rst orthography workshop, it is useful to give examples from Dutch, Eng-

lish, or other prestigious languages which do manifest double vowels in their writing systems (e.g., English

<>, <>).

8

Sometimes a Cy or Cw will condition following length, but a simple glide (w or y) will not. All environ-

ments should be checked before the linguist decides where vowel length is contrastive and where it is not.

9

According to Hyman (2003:52), “In most Bantu languages there is no vowel length opposition before an

NC complex.”

10

A possible exception would be the result of morphemes rather than phonological processes.

17

Chapter 2 - Representing Linguistic Features

vowels is not necessarily an indicator of how they are perceived by speakers. However,

despite their perception that the conditioned length vowels are long, because this length is

not contrastive, the Tharaka orthography does not write the conditioned length with dou-

ble vowels. Thus, readers must be taught (requiring a lesson on prenasalized stops) to write

such vowels as short.

In languages where speakers feel that the vowels in these environments are clearly long,

writing this length, even though it is not contrastive, may make spelling easier for them.

Mother-tongue speakers may want to write all the vowels which sound long to them as

long. This is one of the options for representing conditioned long (CL) vowels.

But because speakers will automatically produce the conditioned length in the condition-

ing environment, they can often best be written with single vowels, even when they are

perceived as long. If the orthography choice is made to represent CL vowels with a single

letter, writers must be taught to write such vowels as short, despite their perception (requir-

ing a literacy lesson on prenasalized stops).

This is the choice taken by the ocial Ganda (EJ13) orthography. A note in the orthog-

raphy statement or worksheet, with examples, will be sucient to explain the simple envi-

ronments that condition the automatic lengthening.

In Ganda, following semivowels and preceding prenasalized stops, vowels are

always written short (http://www.buganda.com/language.htm).

[tuunda] ‘sell’ is written <>

[kitaanda] ‘bed’ is written <>

[kiimpi] ‘it is short’ is written <>.

There are pros and cons to each option, and these vary from language to language. They

should be discussed by representatives of the language community and choices should be

tested by a literacy specialist and/or a linguist before a nal decision is made.

The disadvantages to writing all long-sounding vowels as long:

• Using double vowels to represent noncontrastive length makes words longer.

• If both contrastive and noncontrastive length are indicated orthographically, truly

contrastive length will not stand out to the reader like it does when double vowels

are used only to indicate contrastive length.

• In some cases, truly contrastive length which results from morpheme concatenation

will be masked by the use of double vowels for the representation of conditioned

vowel length. The following examples can be found under “Other vowel length

issues”.

The disadvantages to writing all vowels with conditioned length as short:

• In languages where tone markings are used frequently, the use of a single vowel

to indicate a vowel with conditioned length can complicate the representation

of falling or rising tone. Such contour tones can be indicated by a sequence of a

high tone mark and a low tone mark for falling tone (or the opposite order for

rising tone) when they occur on a long vowel indicated by two letters. This allows

all tones to be marked using only two symbols. But if a contour tone occurs on a

conditioned long vowel which is represented by a single vowel, it is necessary to

18

Bantu Orthography Manual

introduce a circumex and/or a breve or caron to indicate the contour tone(s).

Discussion of these issues and a good degree of testing the tendencies and perceptions of

both readers and writers will be necessary to determine whether or not conditioned length

should be written with two vowels or one.

In some languages in which there is phonemic vowel length, this length is always

contrastive,

11

even in the environments where length is conditioned in many other lan-

guages. In such a language, either a long vowel or a short(er) vowel may occur in the

conditioned environments, and the long vowels still contrast with short vowels no matter

what the phonological environment is. In such a case, long vowels must always be written

as long, and short ones as short. This is apparently the case in Matuumbi (Odden 2003:532)

as well as in Rangi (F33), where there is contrast preceding a prenasalized consonant in the

following two noun stems:

Rangi: ‘child’ vs. ‘beehive’

We will now look in some detail at various spelling challenges for languages with con-

ditioned lengthening (all highly typical of Bantu languages) and discuss the orthographic

considerations relevant to each.

Sometimes, vowel length (or a series of two consecutive vowels in separate syllables) re-

sults at a morpheme boundary, from the juncture of a vowel-nal morpheme and a vowel-

initial one.

Bungu (F25), which seems to have no phonemic length in stems (Stegen:4), ex-

hibits a contrast in verb tenses that needs to be represented by the use of a double vowel.

This conjoining of two vowels often only happens where the verb stem is vowel-initial, as

in the example here, where the stem is -anda. (See a similar example from Ndali (M301)

later in this section.)

Bungu <> ‘I am beginning’ vs. <‘I have begun’

As Stegen states, long vowels can result from cross-morphemic vowel sequences, at times

involving vowel assimilation in case of nonidentical vowels. This can occur through direct

concatenation as in the following.

Rangi ‘he has shut [implied: the door]’ (from á+ék+ire)

Or it may involve consonant elision as in the following example.

Rangi ‘he has sung for him’ (from á+mú+ímb+ir+ire)

In most cases, such long vowels will be written with double letter, as they can be seman-

tically distinct from the same segmental sequence with short vowel, as demonstrated in the

example below in contrast to the example above.

11

This should not be confused with contrastive length that occurs in these environments only in a few

selected words, occasioned by morpheme concatenation or found in one or two specic grammatical mor-

phemes.

19

Chapter 2 - Representing Linguistic Features

Rangi: ámwiimbíré ‘he should sing for him’ (from á+mú+ímb+ir+é)

However, since Rangi may have contrastive long vowels in all phonological environ-

ments, all their long vowels are written with a double vowel.

Helen Eaton (pc) writes concerning languages in the Mbeya area of Tanzania, “We are

nding that for those languages where lengthened vowels in conditioned environment are

perceived by MT speakers as just as long as underlying long vowels, the morphologically

lengthened vowels also sound just as long, and no longer.” Take Malila (M24), for example.

1 <> ‘to say’

2 <> ‘I have begun’ (from na+anda)

3 <ée> ‘I have taken’ (from na+ega)

4 <i> ‘cl.2-good’ (from abha+inza)

5 <ii> ‘cl.2-black’ (from abha+ilu)

Eaton says, “The underlined vowels are all considered the same length by MT speakers.

If we taught that the morphologically lengthened vowels before NC (2 and 4) needed to be

written long, that would match up with forms like 3 and 5, but dier from forms like 1, in

which the vowel is perceived as just as long.”

As long as there is not any meaning contrast lost by writing all conditioned length vow-

els with a single letter, it is simplest if the rule can be maintained without exception.

Real languages are complex, and even in the extremely regular Bantu languages, there

will be cases which necessitate an exception to your spelling rules. Do not question your

rules just because you nd an exception or two. If you nd extensive and systematic sets of

exceptions, consider revising the rules.

Individual exceptions to the rule of writing conditioned length with a short vowel may

need to be made in cases of verbs with vowel-initial stems. This does not mean that the

“write them short” rule is incorrect or invalid. The exceptions will involve a meaningful

contrast, and this fact may make teaching them fairly concrete. Testing will be needed to

determine the best option for dierentiating otherwise ambiguous words or morphemes.

In Tharaka (E54), vowels are always lengthened about 1½ beats before prenasal-

ized stops. Their orthography follows the practice of writing a conditioned long vowel

with a single letter. This means that they have a spelling rule which says not to write

a double vowel preceding a nasal plus consonant. However, the following words are

contrastive in meaning (quite possibly the second word is actually a clitic plus another

morpheme):<> ‘but’ and <> ‘now’. Since they have dierent meanings, they

need to be written dierently, as vowel length (and tone) in the second word indicates a

20

Bantu Orthography Manual

very distinct lexical item. Thus, they need an exception to their rule, saying that in the

word <> ‘now’ a double vowel must be written, even though it precedes a prenasal-

ized consonant.

Note that if instead the Tharaka writing system simply required that any vowel that

sounds long must be written with a double vowel, both of these words would be written

<>. The contrast in meaning between the two words would be lost.

In Ndali (M301), strict adherence to the rule of writing vowels short in a conditioned

length environment results in neutralized contrasts, such as that between <>‘he

has stamped’ from /a-kanda/ and <> from /a-ka-anda/ ‘and he started’. In such a

case it will probably be best to teach readers and writers to reect the morphemes which

are otherwise involved in the loss of contrast, writing /a-ka-anda/ as <> in order

to maintain the semantic dierence between the two forms. This can be taught in a les-

son focusing on vowel-initial verb stems, which often cause exceptions to length rules, due

to the concatenation of a vowel-nal tense or person morpheme and the vowel-initial verb

stem.

In a case where concatenation results in three vowels in a row, writing them as three

consecutive vowel letters may not be accepted. The following Tharaka (E54) verb in the

distant past exemplies such a situation. The person marker is ba-, the past marker is a-

and the root is -ak-, resulting in three <>’s in a row.

Tharaka: /baaakire/ ‘they built (long ago)’ (from ba+a+ak+ire)

The Tharaka example /baaakire/ is written orthographically as<>, because they

decided to disallow triple sequences of identical vowels in the orthography. Kithinji et al.

give the following explanation.

In some cases it is possible that three identical vowels occur in sequence…

In such cases all three vowels will not be written but only two. For ex-

ample, ba + a + akire, ‘they built’ is written baakire (not baaakire).

This means that in the surface form this will not be distinguished from

the recent past, ba + akire, [also] spelt <>. The two forms are

pronounced with dierent tone patterns, and the context will determine

in most cases which form is intended. (Kithinji et al. 1998:3)

Especially if it can be shown that there is a dierence in the syllable pattern of such a

word, writers may be convinced that writing all three vowels is actually a good option.

In a few Bantu languages, phonemic length has not been retained from Proto-Bantu, but

contrastive length has developed from the loss of intervocalic consonants or morpheme

concatenation. In such cases, there will not be any phonologically conditioned length.

Among these is Tonga (M64) (Maddieson 2003:38).

21

Chapter 2 - Representing Linguistic Features

It is also possible that a contrastive long vowel may be retained in certain tense prexes

even in a language which otherwise has no phonemic vowel length (Nurse 2003:100). This

is especially true of length due to morpheme concatenation or the loss of an intervocalic

consonant, but can also be due to certain retained or regained vocabulary items. Botne

(2003:425) notes that in Lega (D25) long vowels occur most commonly in ideophones

(which generally tend toward onomatopoeia and intonational length) and rarely in other

words—he lists only three other words that have long vowels. Thus, even in a language

with no systematic phonemic vowel length, there can be the need for an occasional double

vowel. This would call for the singling out of such morphemes as teaching points in an or-

thography guide and any literacy pedagogy.

In some languages, there are certain specic vocabulary items which contain sequences

of nasal plus consonant that do not condition length in the preceding vowel. Often these

are not reexes of Proto-Bantu NC sequences, but rather reect the historical loss of a

vowel, usually <u>, from a <mu-> prex. In other cases, they involve a prenasalized con-

tinuant, such as nj, nz, rather than a prenasalized obstruent. The presence of such non-

length-conditioning sequences does not rule out the use of a rule that a vowel be written as

short preceding a prenasalized consonant. Testing should be done, especially with readers,

in such cases.

There are also many cases in Bantu languages in which underlying long vowels undergo

predictable shortening in some contexts:

A number of languages allow a long vowel only in the penultimate or antepenultimate

syllables, and shorten any long vowel which would occur before that. Some languages, like

Safwa (M25) and Kifuliiru (DJ63), count morae rather than syllables and allow no more

than two morae maximum to follow a long vowel. This sort of shortening usually applies

both to conditioned vowel length and to phonemically long vowels.

This may present the need for a spelling rule by which any phonemic length in a verb

stem is preserved in stems which would otherwise lose their contrastive length when sever-

al suxes are added. It is not an issue in nouns and other words which do not have signi-

cant suxation.

The following example (Van Otterloo, pc) shows that from the literacy point of view, it is

sometimes preferable to write underlying length rather than reecting phonological short-

ening in verbs with contrastive length in the stem.

Fuliiru (DJ63) has two verb stems with lexical contrast for vowel

length,<> ‘to put’ and < > ‘to crow’. <> will lose the vowel

length in its radical, phonetically, whenever there are three or more morae following in its

suxes, e.g., with the long causative /–iis/ plus the nal vowel. With the three following

morae, the stem vowel shortens. [-biik-] is shortened to [-bik-] in [kubikiisa] ‘to cause to

put’. If the shortened stem vowel is written with a single letter, the contrast will be neutral-

ized orthographically between the two verbs.

22

Bantu Orthography Manual

The underlying length in the stem should be preserved if testing veries that readers can

learn to identify the verb root, and hence meaning of the whole word, in this way. The verb

radical may be concrete enough that writers would be able to deal with maintaining non-

phonetic length there (Van Otterloo). In this case, then, the verb with causative [kubikiisa]

would be written <>.

The other implication of the presence of a shortening rule is that in an orthography

which represents conditioned vowel length using double vowels, a large percentage of

stems would be aected by any length-preservation rule such as that mentioned in the pre-

vious paragraph. Instead of involving only stems having phonemically long vowels (usually

a relatively small number) it would also theoretically involve any stem in which there is a

phonologically conditioned long vowel.

If a spelling rule preserves the morphemic shape of a verb stem such as [-biik-] above,

this will either necessitate also preserving length in a verb stem such as [-geend-] (in which

the vowel length is merely conditioned, and not contrastive) or else readers and writers will

need to be taught to dierentiate between phonemic and conditioned length when decid-

ing which length to retain. If the decision is made to retain all length, testing will need to

be done to determine whether it is possible for readers and writers to identify the verb root

and to determine that in its unsuxed form it exhibited phonological vowel lengthening.

This extrapolation might be dicult enough that it would outweigh the ease factor of a

decision to write all vowels that sound long with a double letter, and be a factor in deciding

to write conditioned long vowels with a single letter in all instances.

• Languages with phonemic length contrasts write single versus double vowel letters,

e.g., <> vs. <>.

• Long vowels resulting from morpheme concatenation should be written with double

letter, at least in cases where meaningful contrast would otherwise be neutralized.

• Conditioned length vowels which are perceived as short should be written with

single letter.

• Vowels which occur in an environment which conditions length in the language,

but which are perceived as extra long (i.e., there is a tone change across the vowel,

or the length results from morpheme concatenation and is perceived as longer

than that of monomorphemic conditioned length vowels in the same environment)

should generally be written with double letter, subject to testing of readers and

writers. Such words will need to be taught as exceptions to the rule of writing a

single vowel in a phonological environment which conditions vowel length.

Mother-tongue speakers’ perception of a vowel as a consonant in certain contexts will

probably determine your choice of symbols for semivowels. Again, however, certain ambi-

guities can be created when a phonemic (and morphemic) distinction is lost when replacing

a certain vowel with the semivowel. For a ve-vowel language this is rarely a problem.

/i/ is always written as <> before any other vowel besides itself, and /u/ is always

written as <> before any vowel besides itself, as shown below.

12

12

A morpheme is lost, though, when two identical ones adjoin, as can be seen in /mi+i/ <miri> and /

u+u/, <unga> in the Duruma example above.

23

Chapter 2 - Representing Linguistic Features

from Duruma (E72d) nouns, showing what happens at the juncture of noun

class prexes and vowel-initial roots:

class 4 pl: mi-

mi + iri → <> bodies

mi + ezi → <> months

mi + adine → <> trees, sp.

mi + oho → <> res

mi + uho → <> rivers

class 14 sing: u-

u + ira → <> song

u + embe → <> razor blade

u + ari → <> food from maizemeal

u + ongo → <> brain

u + ungs → <> our