East Tennessee State University East Tennessee State University

Digital Commons @ East Digital Commons @ East

Tennessee State University Tennessee State University

Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works

8-2020

ACT Scores and High School Cumulative Grade Point Average as ACT Scores and High School Cumulative Grade Point Average as

Indicators of College Graduation at one High School in East Indicators of College Graduation at one High School in East

Tennessee Tennessee

Ariane Day

East Tennessee State University

Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd

Part of the Educational Leadership Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Day, Ariane, "ACT Scores and High School Cumulative Grade Point Average as Indicators of College

Graduation at one High School in East Tennessee" (2020).

Electronic Theses and Dissertations.

Paper

3791. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/3791

This Dissertation - unrestricted is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital

Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and

Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more

information, please contact [email protected].

ACT Scores and High School Cumulative Grade Point Average as Indicators of College

Graduation at one High School in East Tennessee

________________________

A dissertation

presented to

the faculty of the Department of Educational Leadership and Policy Analysis

East Tennessee State University

In partial fulfillment

of the requirements for the degree

Doctor of Education in Educational Leadership, School Leadership

______________________

by

Ariane Sonia Day

August 2020

_____________________

Dr. Virginia Foley, Chair

Dr. Stephanie Barham

Dr. William Flora

Dr. Donald Good

Keywords: ACT, Bachelor’s Degree Attainment, College Readiness, High School GPA

2

ABSTRACT

ACT Scores and High School Cumulative Grade Point Average as Indicators of College

Graduation at one High School in East Tennessee

by

Ariane Sonia Day

The purpose of this quantitative study was to see if there was a significant difference in the mean

American College Test (ACT) scores and high school grade point average (HSGPA) between

students who attained a bachelor’s degree within 6 years of starting college and those who did

not attain a bachelor’s degree within 6 years of starting college. Data from 2005-2013 high

school graduates from one high school with only academic course choices were used. A series of

independent t-tests were used to compare the mean ACT scores and HSGPA of students from

both groups.

The goal was to find out whether high school educators can use existing high school data to

know whether students who intend to continue their postsecondary studies at degree granting

postsecondary institutions have the necessary preparation not just to be admitted to a

postsecondary institution, but to attain a bachelor’s degree. The results showed that for this group

of participants, the mean ACT scores and HSGPA were significantly different between students

who attained a bachelor’s degree within 6 years and those who did not. Using Cohen’s d to

calculate the effect size for the results, ACT Composite, ACT English, ACT Science, and

HSGPA were found to have a large effect size, and ACT Math and ACT Reading were found to

have a medium effect size. HSGPA had the largest effect size.

3

The implications from the results are that high school personnel at all high schools should

examine available data to see if it can be used as indicators of bachelor’s degree attainment with

the purpose of providing additional support to students who intend to pursue a bachelor’s degree,

but whose data indicate that they may not have the necessary preparation to successfully

complete a degree.

4

Copyright 2020 by Ariane Sonia Day

All Rights Reserved

5

DEDICATION

This work would not have been possible without the sacrifices of the people closest to

me:

• To my children Matthias, Janine, Kirsten and Luke, for picking up the slack while I was

pursuing this goal.

• To my husband Nathan, for loving me for the past 28 years, for believing in me, and for

supporting me always.

And in addition, it would not have been possible without the help, support, and

encouragement of many:

• To my parents, Edgar and Monika Affolter, for loving me and raising me to work hard

and not give up.

• To my uncle, Dr. Rolf Sutter, for being an inspiration in reaching this level of education.

• To Pat, for mentoring me and being my dear friend for the past 19 years.

• To the many extended family members, friends and colleagues who have encouraged me

on this journey by reminding me that I could do it when I struggled to believe in myself

and to find the motivation to keep going.

6

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to sincerely thank the members of my committee for their help and support

along the way. Thank you for your time and invaluable feedback throughout this process. Thank

you, Dr. Foley, for nagging me to finish and answering my many questions. Thank you, Dr.

Flora, for helping me brainstorm and refining ideas. Thank you, Dr. Good, for helping me with

the statistics and for your feedback. Thank you, Dr. Barham, for your feedback, kindness and

encouragement.

7

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................................... 2

DEDICATION ................................................................................................................................ 5

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................................ 6

LIST OF TABLES ........................................................................................................................ 10

LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................................... 11

Chapter 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................. 12

Statement of the Problem ...................................................................................................... 13

Research Questions ............................................................................................................... 15

Significance of the Study ...................................................................................................... 16

Limitations ............................................................................................................................ 17

Delimitations ......................................................................................................................... 18

Definitions of Terms ............................................................................................................. 18

Chapter Summary ................................................................................................................. 20

Chapter 2. Review of Related Literature ................................................................................... 21

American College Test ......................................................................................................... 21

Grade Point Average ............................................................................................................. 23

High School Credits .......................................................................................................... 23

Quality Points ................................................................................................................... 25

8

Cumulative Grade Point Average Calculation .................................................................. 25

Importance of the ACT Score and HSGPA .......................................................................... 26

Bachelor’s Degree Attainment .............................................................................................. 32

Importance for Society ...................................................................................................... 32

Importance for Postsecondary Institutions ....................................................................... 33

Importance for Students .................................................................................................... 35

Importance for High Schools. ........................................................................................... 39

Purpose of High School and High School Accountability ........................................... 39

Recommended Areas of Improvement for High Schools ............................................. 41

Predictors of College Success ............................................................................................... 45

Chapter Summary ................................................................................................................. 53

Chapter 3. Methodology ............................................................................................................ 55

Research Questions and Corresponding Null Hypotheses ................................................... 56

Population ............................................................................................................................. 58

Instrumentation ..................................................................................................................... 60

Data Collection ..................................................................................................................... 60

Data Analysis ........................................................................................................................ 61

Chapter Summary ................................................................................................................. 61

Chapter 4. Findings ................................................................................................................... 63

Research Question 1 ............................................................................................................. 63

9

Research Question 2 ............................................................................................................. 65

Research Question 3 ............................................................................................................. 67

Research Question 4 ............................................................................................................. 69

Research Question 5 ............................................................................................................. 71

Research Question 6 ............................................................................................................. 73

Chapter Summary ................................................................................................................. 75

Chapter 5. Summary, Conclusions, and Recommendations ..................................................... 77

Discussion and Conclusions ................................................................................................. 80

Implications for Practice ....................................................................................................... 84

Implications for Further Research ........................................................................................ 87

Summary ............................................................................................................................... 88

References ................................................................................................................................. 90

VITA ........................................................................................................................................... 103

10

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1. Effect Size, Means and Standard Deviations for ACT Composite and Subscores for the

Two Groups ................................................................................................................... 83

Table 2. HSGPA Effect Size, Means and Standard Deviations for the Two Groups ................... 84

11

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1. ACT Composite Scores Distribution Between the Two Groups ................................... 64

Figure 2. ACT Math Scores Distribution Between the Two Groups ............................................ 66

Figure 3. ACT Reading Scores Distribution Between the Two Groups ....................................... 68

Figure 4. ACT English Scores Distribution Between the Two Groups ........................................ 70

Figure 5. ACT Science Scores Distribution Between the Two Groups ........................................ 72

Figure 6. HSGPA Distribution Between the Two Groups ............................................................ 74

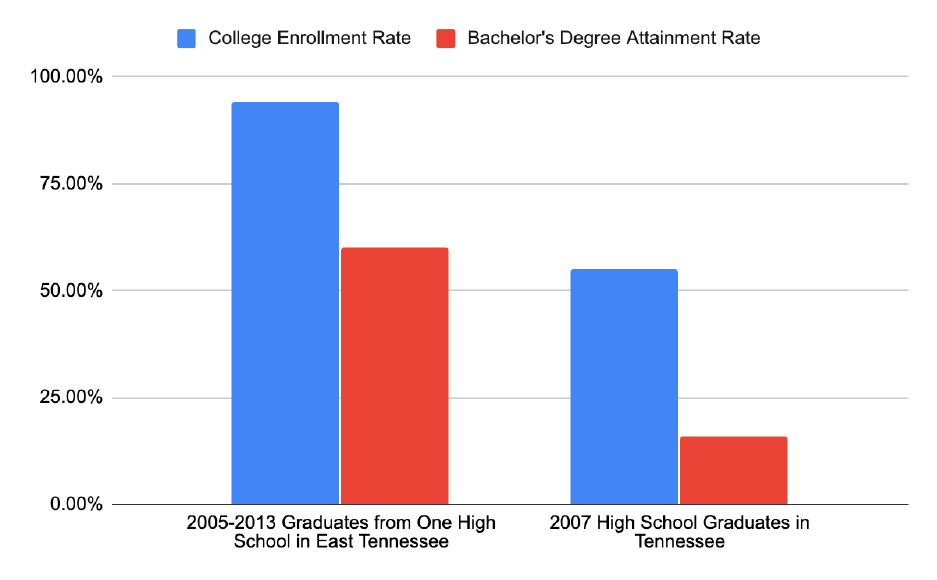

Figure 7. Bachelor’s Degree Attainment Within 6 Years of Starting College ............................. 79

Figure 8. Years to Bachelor’s Degree Attainment for the Participants of the Study .................... 80

Figure 9. Distribution of ACT Score Means Between the Two Groups ....................................... 82

12

Chapter 1. Introduction

High school teachers prepare students for their postsecondary and professional endeavors

(ACT, 2005b; Barth, 2003; Cohen, 2001). High school graduation requirement are established at

the state level by members of the Tennessee State Board of Education (2017). Aside from

prescribed requirements, students may explore course options offered at their school from

vocational, Early Postsecondary Opportunities (EPSO) such as dual-enrollment and State Dual

Credit (SDC) courses, and elective courses among other offerings. Depending on the mission and

the location of the high school, students will have more or fewer choices and opportunities. For

the purpose of this study, the researcher looked specifically at students from one high school in

east Tennessee where only an academic completion pathway is offered. The expectation for

students attending this school is enrollment in a college or university after graduating high school

and complete a bachelor’s degree. Administrators and teachers of high school students who

desire to earn a bachelor’s degree need to be able to determine if students who satisfy the

requirements to earn a high school diploma are both ready to be admitted to college and able to

successfully complete a bachelor’s degree. Ideally, there should be a way for high school

educators to know with certitude that students are ready to pursue a bachelor’s degree and have

the background necessary to complete a bachelor’s degree based on data that are available when

students are in high school. The data most often used in Tennessee to determine college

readiness are the students’ cumulative High School GPA (HSGPA) and their ACT scores.

This is a study of all students who graduated from a small publicly funded college

preparatory high school in east Tennessee between 2005 and 2013, in total about 540 students.

Students who graduated from this school in May 2013 had 6 years to complete their bachelor’s

degree at a postsecondary institution by the time the researcher examined the data. In order to

13

only examine data from students who had up to 6 years to complete a bachelor’s degree, data

from the high school class of 2014 and subsequent classes were not used in this study. The

purpose of this study was to examine whether students who participated in a college preparatory

high school program of study earned a bachelor’s degree within 6 years of beginning

postsecondary studies. Six years represents 150% of the expected time it takes to complete a

bachelor’s degree from the time a student enrolls at a postsecondary institution and it is a

measure of accountability for postsecondary institutions in Tennessee (Tennessee Higher

Education Commission, n.d. a). In this study, the researcher used a series of independent t-tests

to determine if there was a significant relationship between the attainment of a bachelor’s degree

within 6 years and the data available for each student: ACT scores (both composite and

individual subscores) and HSGPA.

Statement of the Problem

High school educators of students who plan to attend college are preparing students with

the goal that they will be successful in college and obtain a bachelor’s degree as a result of

successful completion of bachelor’s degree requirements. Postsecondary success is measured by

completing the required program of study thereby earning a bachelor’s degree from a

postsecondary institution. Students who have earned a bachelor’s degree have been found to earn

a significantly higher income than students who did not earn a college degree (Barth, 2003;

Carey, 2005; Mayhew et al., 2016). Because of this gap in lifetime earning potential, there is a

need for high school teachers and administrators at all high schools to know whether students

who intend to complete a bachelor’s degree are adequately prepared while in high school to

successfully complete postsecondary programs of study and earn a bachelor’s degree. While not

all students intend to pursue a bachelor’s degree, the preparation needed to be ready for college

14

success will benefit students who chose alternative paths after high school (Barth, 2003). High

school graduation requirements and course standards in Tennessee public schools are set by state

lawmakers and in theory are implemented equally across all high schools in Tennessee. The

delivery of the content is in the hands of licensed teachers. Rigor and content, however, vary

from school to school and from classroom to classroom despite having set standards (ACT,

2005b; Adelman, 1999). Because of this discrepancy, there is a need for secondary school

teachers, counselors and administrators to have tools that measure how well students who want

to go to college are prepared for success at the postsecondary level. Students need to be prepared

not just to be admitted, but also to complete a bachelor’s degree. Two important student data

points that are available to teachers, counselors, and administrators in Tennessee at the secondary

level are student ACT scores and subscores as well as student GPA. Educators in the United

States consider those two data points important in determining postsecondary readiness. In an

effort to increase student college readiness, lawmakers in Tennessee enacted a law to provide

one free ACT administration to high school juniors starting with the 2007-2008 school year

(Tennessee Department of Education, 2018a). More recently, it became law that, beginning with

the 2018 high school graduation cohort, high school students in Tennessee were required to take

the ACT in order to earn a high school diploma (Tennessee State Board of Education, 2017;

Tennessee Department of Education, 2018a). The ACT test is administered during the school day

to all juniors at their respective high schools. In an effort to improve college readiness for

Tennessee high school students, the Tennessee State Board of Education added a second

administration of the ACT to all seniors in 2016, essentially giving students two opportunities to

take the ACT test at no cost to them (Tennessee Department of Education, 2018a). Taking the

test several times is recommended as research shows that 40% of students improve their score

15

when taking the ACT a second time (ACT, 2017b; Tennessee Department of Education, 2018a).

Student ACT scores are part of school accountability in Tennessee, but when students take the

ACT more than once, only the highest scores are taken into consideration in the calculation for

school accountability (Tennessee Department of Education, 2018b).

The HSGPA is a calculation where the weight of a course, the credit, is the divisor and

the success value, the quality points earned in that course, is the dividend. It is an easily

interpreted value that is almost universally used by secondary and postsecondary education

institutions in the United States (Volwerk & Tindal, 2012). Student HSGPA and ACT scores are

used at postsecondary institutions to determine admission to the institution, acceptance into more

competitive college programs, and eligibility for scholarships (Barth, 2003; Cimetta et al., 2010;

Volwek & Tindal, 2012). The researcher wanted to know whether these data points, ACT scores

and subscores and HSGPA, can be used by high school personnel as an indicator of whether

students are prepared to be successful at the postsecondary level as measured by the completion

of a bachelor’s degree.

Research Questions

The following research questions were designed to frame the analysis of data for

determining differences between bachelor’s degree attainment and the following high school

student data: ACT Composite scores, ACT Math subscores, ACT Reading subscores, ACT

English subscores, ACT Science subscores, and HSGPA.

RQ1: Is there a significant difference in the ACT Composite scores between students

who completed a bachelor’s degree within 6 years of starting college and students

who did not complete a bachelor’s degree within 6 years of starting college?

16

RQ2: Is there a significant difference in the ACT Math subscores between students who

completed a bachelor’s degree within 6 years of starting college and students who

did not complete a bachelor’s degree within 6 years of starting college?

RQ3: Is there a significant difference in the ACT Reading subscores between students

who completed a bachelor’s degree within 6 years of starting college and students

who did not complete a bachelor’s degree within 6 years of starting college?

RQ4: Is there a significant difference in the ACT English subscores between students

who completed a bachelor’s degree within 6 years of starting college and students

who did not complete a bachelor’s degree within 6 years of starting college?

RQ5: Is there a significant difference in the ACT Science subscores between students

who completed a bachelor’s degree within 6 years of starting college and students

who did not complete a bachelor’s degree within 6 years of starting college?

RQ6: Is there a significant difference in HSGPA between students who completed a

bachelor’s degree within 6 years of starting college and students who did not

complete a bachelor’s degree within 6 years of starting college?

Significance of the Study

Many studies have compared ACT Composite scores, ACT subscores, and HSGPA with

student success in college at various levels as well as with the ultimate earning of a college

degree (ACT, 2008b; Hein et al., 2013; Noble & Sawyer, 2002). However, the focus of many

researchers was not on the completion of postsecondary studies as measured by attainment of a

bachelor’s degree. Few studies have examined the relationship between high school student data

and attainment of a bachelor’s degree from a specific high school perspective and with the intent

to improve postsecondary preparation at the secondary level. While many students go to college

17

after finishing high school and complete one year or even more, not all students who begin

college do so with the intent to earn a degree (Bradburn, 2002). In this study, the researcher

examined students who graduated from one college preparatory high school that is a school of

choice, not the students’ designated Local Education Agency (LEA). Parents or guardians of

students had to apply for students to attend this high school and understood that the goal of this

high school is to prepare students to continue their studies at the postsecondary level. The goal

for students to complete a bachelor’s degree was evident by the lack of vocational class offerings

that would allow students to explore career choices that do not require pursuing a bachelor’s

degree. Based on this information, the assumption was made that the expectation was for

students to enroll in a college or university after graduating from high school with the intent to

complete a bachelor’s degree.

Tennessee’s high school graduation requirements were revised in 2017 (Tennessee State

Board of Education, 2017). The revised requirements match recommendations from ACT of the

high school coursework necessary for students to have an increased probability of completing

college with a bachelor’s degree. According to Barth (2003), 80% of high school students plan to

go on to college after high school. High school teachers, counselors and administrators need

indicators to determine if they are preparing students to be successful in college.

Limitations

This study was limited to examining student HSGPA, highest ACT Composite score and

highest ACT subscores, and bachelor’s degree attainment within 6 years of high school

graduation. In this study, the researcher did not take into account other student factors that are

known to improve or diminish bachelor’s degree attainment rates. Because the ACT is a

nationally normed test, academic exposure factors that affect student postsecondary preparation

18

before college would be reflected in their scores. The better the academic preparation in and out

of the classroom, the better the ACT scores. Another factor that is not considered is the

graduation rate of each postsecondary institution. Joy (2017) compared predicted bachelor

attainment rates to actual bachelor attainment rates and found that some postsecondary

institutions have better success graduating students than others regardless of students’ prior

preparation. According to the National Center for Educational Statistics (2019) and the U.S.

Department of Education (2019), the overall rate of bachelor attainment for full-time students

was 60%. However, there were many variations depending on the institution. Private for-profit

institutions had the lowest graduation rates with 20% for women and 22% for men. Institutions

with the lowest acceptance rates and the highest selectivity had the highest graduation rates with

87%. Non-selective institutions also had a low graduation rate at 31%.

Delimitations

For this study, data from students attending one small high school in east Tennessee were

used. Factors that affected college graduation rates that may have only been present at this one

high school are inevitable.

Definitions of Terms

In this study, specialized educational vocabulary for secondary and postsecondary levels

were used. It is important to understand the following terms as they related to this study:

• ACT Composite score: The American College Test, or ACT as it is now called, is a

college admission’s test that is accepted by all 4-year colleges and universities in the

United States (ACT, 2018). The ACT test is not an IQ or aptitude-based test. Instead it

measures what students have learned in high school in the areas of math, English, reading

19

and science. The highest possible ACT Composite score is a 36, and it is an average of

the 4 tested areas.

• ACT subscores: the ACT measures students’ knowledge in 4 areas: math, English,

reading, and science. Each area receives an individual score, which are called subscores,

with the highest possible score being a 36.

• Bachelor’s degree: a bachelor’s degree is a postsecondary degree awarded for successful

completion of undergraduate studies in postsecondary institutions, specifically colleges

and universities, and it is the difference between being enrolled as an undergraduate

student or a graduate student (Wallace, 2009). A bachelor’s degree typically takes about

4 years to complete but can be completed faster or slower depending on how many

credits a student completes during a semester among other factors.

• High school cumulative unweighted grade point average: a number on a scale of 4 that

represents students’ overall success in their high school classes over the span of their high

school career. In courses where students earn credits, a letter grade from A to F is

assigned to quantify how well students have learned the material of the course (U.S.

Department of Education, 2008). Tennessee has set a grade scale for secondary schools

where an A represents a percentage grade of 93%-100%, a B is 85%- 92%, a C is 75%-

85%, a D is 70-74% and an F is 69% or below (Tennessee State Board of Education,

2017). To calculate a grade point average, each letter is assigned points on a four-point

scale: a grade of A equals 4 points, B equals 3 points, C equals 2 points, D equals 1 point,

and F equals 0 points. The points are then added, and the total is divided by the total

number of attempted credits (a failed course is still an attempted credit) resulting in a

cumulative unweighted grade point average (U.S. Department of Education, 2009).

20

Chapter Summary

There is a need for teachers, counselors and administrators at secondary schools to know

how well they prepare students for their next step after graduating from high school, whether

they plan on continuing their studies at a postsecondary institution or not. ACT (2005a; 2005b;

2008b) has identified what courses have the best results in preparing students for college and

work, and the Tennessee State Board of Education (2017) has increased the high school

graduation requirements to included many of those recommended courses. ACT scores and

HSGPA are two data points that are available statewide in Tennessee. The researcher wanted to

know if these data points can be used by teachers, counselors and administrators to determine

student readiness to complete a bachelor’s degree, especially in a school that offers only a

college preparatory path. This study is significant because while many studies have examined

ACT scores and HSGPA in relation to college success, that success was most often measured in

terms of year to year retention and not bachelor’s degree attainment. The participants of this

study were graduates from a small college preparatory high school in east Tennessee.

21

Chapter 2. Review of Related Literature

In order to understand this study, one must first gain an understanding of what the ACT

and HSGPA are, how they came to be, how they are calculated, and their current relevance. It is

also noteworthy to highlight the importance of the ACT and HSGPA when it comes to admission

to postsecondary institutions, scholarship eligibility, and other placement decisions based on

those scores. Looking at the reasons why attaining a bachelor’s degree is important and also

provides information for the relevance of this study. Finally, looking at the predictive abilities of

the ACT and the HSGPA as found in the literature provided the basis for this research.

American College Test

The American College Test (ACT) is a college admission test that is typically accepted

by 4-year colleges and universities in the United States (ACT, 2018). According to the U.S.

Department of Education (2016), the ACT was introduced in the 1950s as an alternative to the

Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT) which was widely used as a college admission tool in the 1940s.

The SAT had begun being used in 1926 as a way to improve the objectivity of the college

admission process (Beale, 2012). Both the ACT and the SAT were commonly used since their

inception to the present day, and both have undergone changes since their inception. Beale

(1970) found that the importance of college entrance exams like the ACT and SAT grew

tremendously in the 1950s in an effort to make college admissions more efficient and based on

the idea that standardized entrance exams were more reliable than previous methods of

admission. Previous to this, the typical college admission was based on a review of high school

records, available test scores, recommendations, and interviews with the applicants.

22

According to ACT (2018), the ACT test is not an Intelligence Quotient (IQ) or aptitude-

based test. Instead, the ACT measures what students have learned in high school. The Tennessee

Department of Education (2018a) considers the ACT to be a national measure of student

readiness for postsecondary work and employment. Students are encouraged to choose more

challenging courses throughout their high school career to be better prepared for college (ACT,

2018). Critics of the ACT however, argued that it should not be used as a national measure of

student readiness because it assesses student mastery of a specific curriculum even though there

are no national standards and because the test is norm-referenced and does compare student

performances against other students (Atkinson & Geiser, 2009).

The ACT test is comprised of four areas that each receive a score, which are called

subscores. The four subscores are averaged into a composite score. The highest possible score

for any subscore and for the composite is a 36. There is also an optional writing portion of the

ACT test that receives a score between a 2 and a 12 which is not taken into consideration in the

composite score (ACT, 2018). For the purpose of this study, the optional writing test was not

considered because it was not consistently taken by students and because it was not factored into

the composite score.

The ACT is designed to give students and colleges a nationally normed score that can be

utilized to interpret a student’s level of readiness to meet the requirements for college readiness

(ACT, 2008a). The scores do not rank the students against one another, although students can

find state averages and national averages to which scores may be compared. The subscore

benchmarks indicating college success are currently set at 18 for ACT English, 22 for ACT

Reading, 22 for ACT Math and 23 for ACT Science (ACT, 2017a). Small variations in the

benchmark scores have happened due to renorming, as ACT sets those benchmarks based on

23

student performance in college classes (ACT, 2010). In 2010 for example, the benchmark for the

science subscore was 24 instead of the current 23, and the benchmark for the reading subscore

was 21 instead of the current 22 (ACT, 2010). A student meeting the benchmarks in each area

has a 50% probability of earning a B or higher and about a 75% probability of earning a C or

higher in the corresponding college course (ACT, 2010).

Grade Point Average

The HSGPA is the result of a division of earned quality points divided by attempted

credits. In order to understand what the HSGPA is, one must gain an understanding of what

credits and quality points are.

High School Credits

In the United States, the accepted measure of educational progress at the high school

level and at postsecondary institutions is the Carnegie Unit which is called “credit” (Silva et al.,

2015). In 1905, Andrew Carnegie donated $10,000,000 to create a pension fund for college

professors. This resulted in the creation of the Carnegie Unit so that the work of college

professors could be quantified, and it could be established who qualified for the pension. It

indirectly resulted in defining high school and college graduation expectations as a measure of

how much time students spent on a subject with the quality of students’ time being measured by

grades assigned by teachers and professors. At the high school level, one credit translates to 120

hours of instruction over the length of one school year (U.S. Department of Education, 2009;

Silva et al., 2015). At the postsecondary level, credit definitions vary from institution to

institution, but the U.S. Department of Education established a guideline to help accredited

institutions define what a credit is (East Tennessee State University, 2017a; Schulte, 2016). The

24

credit measure is used in the calculation of the Grade Point Average (GPA) and has become a

fundamental measure of the American educational system. At the postsecondary level, federal

financial aid can only be granted to students who attend institutions that use the Carnegie Unit

system of measurement of educational achievement (Schulte, 2016; Silva et al., 2015).

Standardization of expectations allowed high schools and colleges to have a workable measure

that facilitated recognizable achievement, but there is still much variation in student achievement

due to rigor differences and professional freedom from one professor to another and from one

institution to another. According to Silva et al. (2015), postsecondary institutions often reject

transfer credits from other institutions, which reflects that the credit is not a good measure of

achievement and lacks details of the actual achievements of the student. The Carnegie Unit is a

measure of time investment and does not have a standard measure of the outcome in terms of

achievement or student competency.

Postsecondary institutions set graduation requirements for their undergraduate and

graduate programs based on successful completion of required courses and the completions of a

set number of credits. At the secondary level, states implemented requirements for high school

graduation. The U.S. Department of Education (2009) reported that from 1990 to 2009, the

average total of credits earned by high school students rose from 23.6 to 27.2. Tennessee for

example requires a minimum of 22 credits to graduate, with specific requirements: 4 credits of

English, 4 credits of math with at least one above the Algebra 2 level, 3 credits of science, 3

credits of science, 3 credits of social studies, 0.5 credit of personal finance, 1 credit of Wellness,

0.5 credit of physical education, 2 credits of the same foreign language, 1 credit of fine arts, and

3 credits of elective focus courses (Tennessee State Board of Education, 2017). In 2009, the U.S.

Department of Education defined three levels of high school curricula and discussed the

25

preparations required at the different levels. A curriculum requiring four credits of English, three

credits of mathematics, science, and social studies respectively is considered standard. A

midlevel curriculum requires four credits of English, three credits of mathematics which include

Algebra 1 and Geometry, three credits of science which include two of either Biology,

Chemistry, or Physics, three credits of social studies, and one credit of a foreign language. A

rigorous curriculum requires four credits of English, four credits of mathematics which include

Pre-calculus or a higher level, three credits of science which include Biology, Chemistry and

Physics, three credits of social studies, and three credits of a foreign language. In 2009, 75% of

high school graduates completed a curriculum that was at the standard level or above (U.S.

Department of Education, 2009).

Quality Points

In courses where students earn credits, a letter grade is assigned to quantify how well

students have learned the material of the course (criterion-referenced) or how the students rank

against either other in the course (norm-referenced) (U.S. Department of Education, 2008). With

either norm-referenced or criterion-referenced, it is common knowledge that letter grades from A

to D signify that the students have passed the course and earned the credit. A grade of F signifies

that the students did not pass the course, and that no credit was earned.

Cumulative Grade Point Average Calculation

To calculate a grade point average, each letter is assigned quality points on a four-point

scale for unweighted GPA calculations and on a five-point scale for weighted GPA calculations:

a grade of A equals four points (five points for weighted calculations), B equals three points

(four points for weighted calculations), C equals two points (three points for weighted

calculations, D equals one point (or two points for weighted calculations), and F equals zero

26

points for both weighted and unweighted calculations since no credit is earned with an F. The

points are then added together, and the total is divided by the total number of attempted credits (a

failed course is still an attempted credit) resulting in a cumulative grade point average (Uribe &

Garcia, 2012; U.S. Department of Education, 2009).

Importance of the ACT Score and HSGPA

For college admission purposes, prestigious postsecondary institutions relied heavily on

high school performance as reported by the HSGPA and class ranking (Uribe & Garcia, 2012).

High school students aspiring to attend postsecondary institutions took college entrance exams,

either the ACT or the SAT (Southern Regional Education Board, 2014; U.S. Department of

Education, 2016). For students, parents, secondary and postsecondary institutions, the ACT was

an easily understood number that corresponded to the likeliness of students performing well in

basic college courses (ACT, 2005b; Southern Regional Education Board, 2014; Tennessee

Department of Education, 2018a). According to Barth (2003), in order to make admission

decisions many postsecondary institutions want to see nationally normed student data such as

ACT scores in addition to class ranking and grade point average. More recently, many public and

private postsecondary institutions have changed their admission policies to no longer requiring

minimum scores on the ACT or SAT for college admission (Furuta, 2017; Southern Regional

Education Board, 2014). For postsecondary institutions that were less selective and that may not

have required a minimum entrance exam for general admission, these data points were still used

for admission into selective programs such as nursing and physical therapy for example (Cimetta

et al., 2010). In stark contrast to postsecondary institutions stepping away from college

admission testing, the state of Tennessee made taking the ACT a graduation requirement for high

school students (Tennessee Department of Education, 2018a, 2018b). Of the 16 states who were

27

members of the Southern Regional Education Board, Tennessee and five other states added ACT

or SAT scores as a part of school accountability formula in the area of college readiness

(Southern Regional Education Board, 2014). The Tennessee Department of Education’s (2018a)

goal was to increase the number of students who graduated from high school ready for their next

step, whether it be more education or employment, and the ACT was the chosen measure to

determine that readiness.

Entrance exam scores such as the ACT and SAT are not only used to determine

admission, they are also used to determine eligibility for scholarships and scholarship retention

(U.S. Department of Education, 2016). To understand how this affects students from the eastern

Tennessee region, admission requirements and scholarship criteria for 13 local public and private

postsecondary institutions awarding bachelor’s degrees were examined. The following

institutions both inside and outside of the state of Tennessee were researched: East Tennessee

State University, Lincoln Memorial University, Milligan College, Tusculum University, King

University, Lipscomb University, Belmont University, Vanderbilt University, Appalachian State

University, Middle Tennessee State University, The University of Tennessee, Knoxville,

University of North Carolina, Ashville, and Western Carolina University. While these

institutions were not necessarily representative of all postsecondary institutions across the United

State, they were examples of small and large institutions, public and private, and were

representative of institutions that students from eastern Tennessee were likely to attend.

The following information pertaining to admission and scholarship requirements was

gathered:

28

• All 13 postsecondary institutions researched required students to submit an ACT or SAT

score for admission whether the use of the score (admission, scholarship, remedial

placement) was specified or not.

• Four out of the 13 institutions required a minimum ACT and HSGPA for regular

admission (East Tennessee State University, 2017b; Lincoln Memorial University, 2020;

Milligan College, 2020a; Tusculum University, n.d.).

• Nine of the 13 institutions did not have minimum admission requirements in terms of

benchmark ACT scores and HSGPA. The following institutions did reference ACT

and/or GPA in their admission information:

o A preference in terms of ACT score and HSGPA for admission as a first-time

college student was listed for admission to King University while not required

(King University, 2020).

o Lipscomb University (2020) displayed an average HSGPA of 3.78 for freshmen

admissions.

o Belmont University (n.d.) explained that applicants rank in the top half of their

graduating class and that there needed to be a strong correlation between

standardized test scores and high school grades.

o Vanderbilt University (2020) listed profile information for the Fall 2019 freshmen

admissions. The admission rate of all first-time freshmen applicants was 9.1% and

the admitted students had an ACT middle 50% range of 33 to 35 score for the

2019 freshman class.

29

o Appalachian State University (2020) also listed profile information for the Fall

2019 freshmen admissions. The middle 50% range of admitted freshmen were an

ACT of 23-28 and a weighted HSGPA of 3.94-4.48.

• Three of the 13 institutions noted that the scores on the ACT and SAT would be used to

determine placements in classes. East Tennessee State University and Middle Tennessee

State University use the ACT score for placement in Learning Support Classes for math

and English courses (East Tennessee State University, 2017b; Middle Tennessee State

University, 2020a). Students with scores below an 18 on their ACT English subscore, or

below a 19 on their ACT Reading or ACT Math subscores are required to enroll in

learning support courses. At East Tennessee State University, these classes are regular

education classes but are designed to provide additional support to students in their area

of identified deficiency and require participation in a learning lab (East Tennessee State

University, 2020a). At Middle Tennessee State University, the prescribed classes are

additional classes that count as elective classes or count as general education requirement

(Middle Tennessee State University, 2020b). The University of Tennessee, Knoxville,

uses students’ ACT Math scores to determine math prerequisites. If a student’s program

requires a specific math course, but the student’s placement level is below that class, they

will need to take their identified prerequisite before being able to take the required math

(The University of Tennessee, 2020c).

• The University of Tennessee (2020b) and the University of North Carolina Asheville

(2020) listed no benchmark requirements for regular admission in terms of ACT score or

HSGPA and did not list average demographics of their incoming freshmen in terms of

ACT Composite score averages or HSGPA averages.

30

• Western Carolina University (2020) did not list benchmark score requirements but had

benchmark requirements of 4.0 HSGPA and 30 ACT score to be admitted to the honors

college.

Scholarships were merit-based by the fact that they use ACT or SAT scores as well as

HSGPA for initial eligibility. Duffourc (2006) reviewed state-funded scholarships that were

available at the time of her publication. Of the 14 state-funded scholarships, 11 had a minimum

ACT or SAT requirement for eligibility and 10 had a minimum HSGPA requirement. In

Tennessee, the Hope Scholarship was a state operated merit-based scholarship that was first

awarded in the fall semester of 2004 (Tennessee Higher Education Commission, 2013). High

school graduates were eligible for the Tennessee Hope Scholarship if they had either a 21 ACT

Composite score, or a 3.0 HSGPA (Tennessee Higher Education Commission, n.d. b). In

addition to the Hope Scholarship, students who had a 3.75 or higher HSGPA and a 29 or higher

ACT Composite score were eligible for the General Assembly Merit Scholarship (GAMS).

Individual institutions also offered a range of scholarships, merit based and need based. Some

examples of merit-based scholarship were:

• East Tennessee State University (2020b, 2020c) offered the Academic Performance

Scholarship with varying levels of award depending on eligibility based on ACT

Composite scores and HSGPA.

• East Tennessee State University (2020d) offered a selective Honors College Scholarship

with a minimum ACT Composite score requirement of 29 and a 3.5 or above unweighted

HSGPA.

31

• The University of Tennessee (2020d) offered the Volunteer Scholarship with varying

levels of award depending on ACT/SAT Composite scores, beginning with an ACT score

of 28.

• Milligan College (2020b) offered Academic Merit Scholarships of varying award

amounts depending on eligibility based on ACT Composite scores and HSGPA.

As highlighted by these examples, student ACT scores and HSGPA were found to be of high

importance at many colleges and universities for admission purposes and for scholarship

eligibility. Fields and Parsad (2012) found that postsecondary institutions solely use college

readiness test scores to determine placement in remedial classes. This was evident in 3 out of the

13 postsecondary institutions researched and referenced above. East Tennessee State University

used the ACT English, ACT Reading and ACT Math subscores for placement in Learning

Support courses (East Tennessee State University, 2020a). The University of Tennessee (2020a)

determined students’ mathematical level using the ACT Math subscore and mandates

prerequisite courses based on the identified level. While only three listed the use of ACT scores

to determine course placement, all required ACT or SAT scores for admission, and more could

be using these scores for placements while not actually publishing this on their admission

information pages. The reliance on a single data point to make the determination for remedial

placement increases the likelihood of student being placed in remedial classes when they did not

need to be, thereby potentially adding time and cost to students’ attainment of a bachelor’s

degree. Hodara and Lewis (2017) reported that community colleges are changing their policy on

remedial course assignments to include multiple data points.

32

Bachelor’s Degree Attainment

The research outlined in this section supports that the attainment of a bachelor’s degree

makes a significant difference in an individual’s qualify of life. The benefits do not stop there:

having more educated citizens has benefits for society as a whole. Postsecondary institutions also

benefit from students completing their programs of study and earning a degree.

Importance for Society

Stewart (2012) and Rolfhus et al. (2017) made the argument that earning a degree is

important not just for the student, but also for society as a whole. For society, having uneducated

citizens results in higher unemployment rates, which in turn results in a slower economy and

higher costs of law enforcement, prisons, and welfare. Educated citizens are more likely to be

employed, contribute more to the economy and pay more taxes, and raise healthier children

(Stewart, 2012). Carnevale and Desrochers (2002) reported that 60% of jobs are filled with

workers with some postsecondary training. Workers with a high school education or less

therefore have fewer opportunities at being hired for a job where they can make a living wage.

According to a policy report completed by ACT (2005a) in 2005, the prediction for 2008 was

that there would not be enough postsecondary graduates to fill the available jobs. The cost of

having uneducated citizens is more than the cost of investing in education to improve the

outcomes (Greene, 2000). Barth (2003) also argued that normal everyday life has gotten more

complicated and requires citizens to be able to reason at an increased intellectual level than

previously needed. Barth furthermore made the point that the preparation needed for college has

become more and more similar to the preparation needed to be successful in the workplace.

Additionally, education has been found to be an equalizer that closes the income gaps between

citizens of various ethnic backgrounds (Barth, 2003; Finn et al., 2015; French et al., 2015).

33

According to Barth (2003), 73% of African American students who begin postsecondary studies

with a strong high school preparation earn a bachelor’s degree. Conversely, less than half of all

African American students who begin postsecondary studies earn a bachelor’s degree. For Latino

students, 61% who begin postsecondary studies earn a bachelor’s degree, but for those who enter

college with an adequate preparation, 79% of them earn a bachelor’s degree. French et al. (2015)

found that when compared to white students with the same HSGPA scores, same school

characteristics and background characteristics, African American students do better in the formal

educational system as measured by degree completion.

Importance for Postsecondary Institutions

The importance of degree completion for higher education institutions has increased

recently with a shift toward a performance-based funding model and accountability based on

output such as degree completion (ACT, 2008b). Banta and Fisher (1984) found that the 1980s

saw a shift of evaluation of higher education institutions from input to an evaluation based on

output. Before this shift, universities’ success was evaluated by such factors as the number of

faculty members holding a terminal degree, library collection size, and money spent per student

among others, all of which are measures of how much an institution invests into its students. In

1979, the Tennessee Higher Education Commission began experimenting with funding based on

performance standards, which measure the impact that institution has on students. Tennessee

higher education institutions could earn an additional 5% of their state allocation for meeting set

performance standards (Banta & Fisher, 1984; Dougherty & Reddy, 2011). While the new focus

was not based on graduation rates, it was mostly based on program quality, student learning, and

the presence of a mechanism for stakeholder feedback and consistent improvement (Banta &

Fisher, 1984). Dougherty and Reddy (2011) established that there were two rounds of

34

performance-based funding, which they called Performance Funding (PF) 1.0 and 2.0. PF 1.0

funding models were established in the 1980s and 1990s in Tennessee, Florida, Ohio and

Washington. These programs were set up as incentives available in addition to the state

allocations already in place. Dougherty and Reddy (2011) established that what they call PF 2.0

funding models are different from the earlier versions. PF 2.0 funding models have performance

requirements that are a part of the state funding formula and are no longer a supplement to the

base funding. Increased accountability on 2-year and 4-year institutions have resulted in more

importance being placed on degree completion (Radunzel & Noble, 2012). Lawmakers across

the country are demanding justification of the public resource investments in higher education

resulting in an increased importance of graduation rates and other output measures rather than

enrollment numbers and other input measures (Dougherty & Reddy, 2011; Radunzel, 2012).

Tennessee implemented the first performance funding policy in 1979, and several states

followed this example (Dougherty & Reddy, 2011). Dougherty and Reddy reported there was an

initial implementation of performance funding policy which was recently replaced by revised

performance funding policies in each respective state. The initial policies have in common the

fact that they reward higher education institutions based on performance indicators with

additional funding. The updated and more recent policies include performance funding into

higher education funding policies and have actually resulted in reduction of overall funding in

some cases. In Tennessee, the revised performance-based funding policy was implemented in

2010 as the Complete College Tennessee Act. Since then, higher education funding is no longer

predominantly based on enrollment numbers. The new funding focus is on performance with

emphasis on course and degree completion (Dougherty & Reddy, 2011). Dougherty and Reddy

determined that there was not a significant increase in graduation rates stemming from

35

performance funding. However, performance funding did have impacts on higher education

institution policies. Braxton (2001) found that a high percentage of students who begin

postsecondary studies but leave before completing a bachelor’s degree caused problems for

institution budgets and public perceptions of the institution. Dougherty and Reddy (2011)

described several examples of policy changes attempting to alleviate the loss of students prior to

degree completion. These policies mostly fit into two categories. Some institutions pass students

through the programs whether they meet the standards or not, thereby weakening their academic

standards. Other institutions developed more selective admission policies in order to select only

students who met the qualifications necessary to be successful allowing the institutions to

maintain program quality but becoming more selective.

Importance for Students

It is general knowledge that it has become a necessity for students to earn some sort of

credentials beyond the high school diploma in order to compete for middle-class jobs that

provide a stable income (Carnevale & Desrochers, 2002; Jimenez et al., 2016; Joy, 2017; Kuh et

al., 2008; Rolfhus et al., 2017; Trusty & Niles, 2004). Barth (2003) found that a majority of high

school students planned on attending a postsecondary institution and earn a degree. ACT (2019)

found that for the 2019 high school cohort, 73% of graduates planned to continue their studies

past high school. For students, earning a bachelor’s degree increased the probability of

significantly higher income over their lifetime. According to Carey (2005), ACT (2005a), and

Carnevale and Desrochers (2002), individuals whose highest education level was a high school

diploma earned about half of what individuals who earned a bachelor’s degree earn. Individuals

who completed an advanced degree earned even more than individuals whose highest education

level was a bachelor’s degree (Carey, 2005). Mayhew et al. (2016) reported that individuals with

36

a bachelor’s degree earned 15% to 27% more than individuals without postsecondary education.

According to Barth (2003), students who did not complete high school earned $2,000 less

annually than high school graduates. High school graduates earned $4,000 less than students who

completed an associate degree, but about $18,000 less than students who earned a bachelor’s

degree. For every unemployed individual with a bachelor’s degree, there are two unemployed

high school graduates. Barth (2003) found that workers with a bachelor’s degree earned on

average $2.1 million over their careers compared to $1.2 million for workers whose highest

education level is a high school diploma. While there was a time when high school graduates

could find a job and work their way up internally to a better pay, today’s higher paying jobs

required additional education and training past the high school diploma from the get-go (Barth,

2003). Carnevale and Desrochers (2002) found that while in 1959, 20% of jobs were filled with

workers who had some postsecondary education, that number was up to 60% in 2002.

According to Tinto (1993, as cited in Braxton, 2001) about 25% of students attending a

4-year institution left during their first year. Bradburn (2002) reported that almost 20% of

students attending a 4-year institution left without completing a bachelor’s degree, more so

during the first year than during their second or third year. Bradburn (2002) found that not all

students who begin postsecondary studies at a 4-year institution were planning on attaining a

bachelor’s degree upon beginning their postsecondary studies which influenced whether they

completed a degree. Of the students who did not complete a degree, 40% did not plan on getting

a degree initially, but 16% did plan on completing a bachelor’s degree. Bradburn found that

students who did not have a regular high school diploma, did not have standardized test scores

(ACT or SAT), delayed their studies after graduating from high school, were part time students,

worked full time while attending college, had to take remedial courses, or had a GPA lower than

37

2.75 were significantly less likely to complete a bachelor’s degree. Trusty and Niles (2004)

studied a group of 3,116 students who were eighth graders in 1988, and who had academic

promise and planned to attain a bachelor’s degree after high school. Of the total participants,

64% attained a bachelor’s degree within eight years after graduating from high school. Trusty

and Niles found that the three most important factors that affected students attaining a bachelor’s

degree were the intensity of the high school preparation, the students' behavior while in high

school, and their socio-economic status.

When looking at the numbers of students not completing a degree, one must keep in mind

that other factors may affect the numbers. For example, Adelman (2006) made the argument that

researchers have not taken into account students who leave one postsecondary institution and

enroll in another. Adelman studied data from a national sample representative of the high school

class of 1992. He observed that of the 1992 graduating cohort, about 60% attended more than

one institution thereby questioning the validity of using college dropout rates as a valid measure

since students leaving one institution to attend another were not taken into account in the data.

Witteveen and Attewell (2017) studied data from almost 9,000 students who began

postsecondary studies at a 4-year institution in the fall of 2004 and accounted for students

changing institutions. They found that students who attained a bachelor’s degree within six years

had certain criteria in common: they varied the intensity of the course work from semester to

semester, and they also took less courses while taking more challenging classes. The students

who did not attain a bachelor’s degree did not show any variation in intensity from semester to

semester or lighter loads while taking more challenging courses.

There are many reasons students do not complete a degree (Kuh et al., 2008). One reason

is that they may graduate from high school underprepared for the expectations of postsecondary

38

work (Barth, 2003; Cohen, 2001; Jimenez et al., 2016; Kuh et al., 2008). Bradburn (2002) found

evidence that lack of preparation affects students completing a bachelor’s degree. Trusty and

Niles (2004) found that math preparation of at least Algebra 2 increased the potential of students

to meet their goal of attaining a bachelor’s degree by 73%. ACT (2005a) and Cohen (2001)

reported that of the 75% of high school graduates who enroll in postsecondary institutions,

almost 30% needed remedial courses (one or more) in math, reading and writing, before being

able to enroll in classes that count toward a degree. From the 1990s to the early 2000s, high

numbers of students enrolled in at least one remedial course (ACT, 2005b). Bailey et al. (2010)

found that 33% of students took remedial English courses and 59% took remedial math classes.

Silva et al. (2015) found that 60% of students attending community colleges take remedial math

classes. Barth (2003) argued that the reason that 25% of first-year college students do not return

for a second year of college is that 50% of college students have to take at least one remedial

course. Taking remedial classes adds more cost and time to the pursuit of a degree since those

classes do not count toward the attainment of a degree. Taking remedial classes has an adverse

effect on students completing the coursework necessary to earn a degree (Adelman, 2004; Barth,

2003; Cohen, 2009; Jimenez et al., 2016). Witteveen and Attewell (2017) found that the

percentage of students who took remedial English, math or other courses was higher for students

who did not complete a bachelor’s degree than for those who did. ACT (2005a) reported that of

the students who took remedial courses in reading, 70% did not earn a postsecondary degree.

For students who took remedial courses in math, 58% did not earn a postsecondary degree.

These statistics are even worse for some subgroups. According to Jimenez et al. (2016), while

35% of white students take remedial courses, the percentages for African American (56%) and

Latino (45%) students are higher, thereby reducing their likelihood of completing a college

39

degree. Jimenez et al. calculated the financial impact of remedial classes to be $1.3 billion per

year, a staggering cost that could be greatly reduced by increasing the college readiness of high

school students.

According to ACT (2005b; 2019) and Barth (2003), the reasons why students do not

complete a college degree can be synthesized into one main reason: the education students

received prior to entering a postsecondary institution did not prepare them for the demands and

expectations of postsecondary work. More than 70% of students graduating from high school

intended at one point or another to go on to college, but the reality is that they were not

adequately prepared to do so (ACT, 2005b; ACT, 2019; Barth, 2003).

Importance for High Schools

To understand the importance of this study for high school teachers, counselors and

administrators, it is important to understand the purpose of high schools. Barth (2003) found that

one of the problems for high school students and their parents is that many assumed that earning

a high school diploma equated with being ready for postsecondary expectations, which was not

always the case.

Purpose of High School and High School Accountability. The purpose of high school

is to prepare students for both the workplace and postsecondary educational opportunities

without the need for remediation (ACT, 2005b; Barth, 2003; Cohen, 2001). More and more, it is

becoming evident that graduates entering the workplace after high school need to be exposed to

similar curriculum and expectations as those entering postsecondary institutions so that they are

successful and enjoy a higher quality of life than less prepared high school graduates (ACT,

2005b; Barth, 2003; Cohen, 2001). Despite this need, many high school graduates lack the

preparation necessary for college as well as the skill necessary to succeed in the workplace

40

(Barth, 2003; Cohen, 2001). One of the problems leading to the lack of preparation, is that while

high schools offer the courses providing adequate preparation for postsecondary work and

continuing studies, these courses are not required to graduate from high school. As a result,

between 30% to 50% of students attending a postsecondary institution after high school did not

take these courses (Barth, 2003). According to Barth, failure to expose students who are not

college bound to foundations that prepare them for postsecondary training and learning is closing

the door to future opportunities. High school graduates might not immediately want to pursue

additional education and training, but as circumstances change and they want to better their lives,

the opportunities would be non-existent without strong foundational knowledge and skills. How

high school preparation is measured is also important because many postsecondary institutions

use both nationally normed tests such as the ACT or SAT for admission and scholarship

determination in addition to high school data such as transcript of coursework, grade point

average, and class ranking. Carnevale and Desrochers (2002) argued that there was a missing

link between secondary school preparation and what was needed to successfully complete

postsecondary education and enter the workforce. They found that this gap began in high school.

High school students preparing for college are taught disconnected academic subjects without an

understanding of the relevance and importance or the connections to postsecondary education

and employment. Students preparing for the work force are not exposed to the academic

background necessary to complete postsecondary education and training thereby closing the door

to future opportunities. Carnevale and Desrochers argued that there is a disconnect between

secondary and postsecondary education that negatively impacts students in their transition from

secondary school to postsecondary institutions or employment.

41

Recommended Areas of Improvement for High Schools. Finding out what high school

administrators, counselors and teachers can do to better prepare students to complete a bachelor’s

degree is important foremost for students. The benefits do not stop there, however. Society as a

whole, secondary and postsecondary education institutions benefit as well. Below are several

areas that secondary institutions can improve upon as discussed in the literature.

Barth (2003) found that while almost 80% of high school students expressed that they

wanted to attend a postsecondary institution after graduating from high school, high school

teachers thought that only about 50% of the students planned on continuing their studies. Barth

argued that there is a lack of communication to high school students and their parents about the

preparation necessary to be successful at the postsecondary level, resulting in students relying on

the high school diploma requirements as adequate preparation for postsecondary work. Barth

(2003) and Venezia et al. (2003) make the point that parents do not have a clear understanding

about the preparation needed to be successful in postsecondary institutions. Parents and students

mistakenly assume that graduating from high school equates to being ready for postsecondary

studies which is not always the case. High school teachers and counselors need to communicate

better with parents and students to inform them of the difference between high school graduation

requirements and college readiness. Trusty and Niles (2004) found that counselors have a crucial

role of helping individual students determine and plan for further education or career paths. ACT

(2008b) found that students who took both the PLANâ test in 10

th

grade and the ACTâ test in

11

th

and 12

th

grades have a high probability of enrolling in a higher education institution (ACT,

2008b).

According to ACT (2005a; 2005b; 2008b; 2017a; 2019), the more rigorous the

curriculum all students are exposed to, the higher their achievement on the ACT test, which

42

reflects their preparation for postsecondary expectations. ACT (2008b) also found that when

students take a more rigorous path, the gender and racial gaps for enrollment and success at

higher education institution are greatly reduced. ACT (2019) recommends a sequence of courses

that best prepares students for college level curriculum and leads to higher ACT subscores and

composite scores. The courses identified by ACT (2005a, 2005b) are: 9

th

, 10

th

, 11

th

and 12

th

grade English, Algebra 1, Geometry, Algebra 2 and at least one more math above the Algebra 2

level, Biology, Chemistry, Physics. Learning at least one foreign language and taking upper-level

math and science courses also benefit postsecondary preparation and result in higher ACT scores

(ACT, 2005a, 2005b). Taking Biology, Chemistry, Physics, and mathematics courses beyond the

Algebra 2 level give students the needed preparation to transition to postsecondary coursework

without needing to take remedial courses (ACT, 2005b). Getting students to take a college

preparatory course sequence while in high school is important. However, it is equally important

to examine the rigor of those courses. Even if students take these courses, the variation in rigor

from one school to another and even one teacher to another cause the outcomes in terms of

college readiness to greatly vary (ACT, 2005b; Adelman, 1999). The quality and rigor of high

school coursework directly affects college success (Adelman, 1999; Barth, 2003). Adelman

(1999) found that high school students who completed at least one math beyond the Algebra 2

level had a much better odds of earning a bachelor’s degree. The American curriculum is too

broad and disconnected compared to other countries scoring better than the United States on the

worldwide Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) assessment (ACT,

2005a; Schmidt et al., 2002; Schmidt, 2005). Other countries like Japan and Germany teach

fewer topics but teach these more in depth allowing for a thorough understanding of the most

important topics rather than a shallow familiarity of important and less important topics alike as

43

is the norm in the United States (Schmidt et al., 2002; Schmidt, 2005). Barth (2003) also argued

that in the United States, there is a tendency to not believe that all students can master more

rigorous coursework. This is another reason why not all students take a rigorous set of courses

that would prepare them for postsecondary work. Research shows that this belief is flawed: low

achieving students perform better in higher level courses than they do in lower level courses.

The transition from secondary to postsecondary has been found to be difficult due to the

disconnect between what students learn in high school and what postsecondary institutions

expect students to know (ACT, 2019; Barth, 2003; Stewart, 2012; Venezia et al., 2003). Trusty

and Niles (2008) recommended collaboration between high school and college counselors in

order to help students prepare adequately for their chosen paths. Radford and Ifill (2016) found

that secondary school counselors have influence on high school students’ postsecondary plans,

and it is important that counselors work with students and their parents on postsecondary plans,

especially at-risk students such as underrepresented students and first-generation college-going

students. There is a need for alignment between what is taught in high school and what is

required for admission to postsecondary institutions and for program completion (ACT, 2008b;

Barth, 2003; Carey, 2005; Cohen, 2001; Venezia et al., 2003).

There is also a need to increase rigor at the high school level (Cohen, 2001). According to

Greene (2000), basic study skills and expectations are lacking in K-12 schools. The expectations