Fire Aboard Small Passenger Vessel Conception

Platts Harbor, Channel Islands National Park,

Santa Cruz Island, 21.5 miles South-Southwest of

Santa Barbara, California

September 2, 2019

Marine Accident Report

NTSB/MAR-20/03

PB2020-101011

National

Transportation

Safety Board

NTSB/MAR-20/03

PB2020-101011

Notation 65936

Adopted October 20, 2020

Marine Accident Report

Fire Aboard Small Passenger Vessel Conception

Platts Harbor, Channel Islands National Park, Santa Cruz Island,

21.5 miles South-Southwest of Santa Barbara, California

September 2, 2019

National

Transportation

Safety Board

490 L’Enfant Plaza SW

Washington, DC 20594

National Transportation Safety Board. 2020. Fire Aboard Small Passenger Vessel Conception

Platts Harbor, Channel Islands National Park, Santa Cruz Island, 21.5 miles South-Southwest of

Santa Barbara, California, September 2, 2019. Marine Accident Report NTSB/MAR-20/03.

Washington, DC.

Abstract: This report discusses the September 2, 2019, fire on board the 75-foot-long small

passenger vessel Conception, operated by Truth Aquatics, Inc., in Platts Harbor on the north side

of Santa Cruz Island, 21.5 nautical miles south-southwest of Santa Barbara, California. Thirty-

three passengers and one crewmember died. Safety issues identified in this report include the lack

of small passenger vessel regulations requiring smoke detection in all accommodation spaces, the

lack of a roving patrol, small passenger vessel construction regulations for means of escape, and

ineffective company oversight. As part of its accident investigation, the National Transportation

Safety Board makes ten new safety recommendations to the US Coast Guard, associations that

have members operating small passenger vessels with overnight accommodations, and Truth

Aquatics, Inc.; the NTSB reiterates one safety recommendation to the Coast Guard.

The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) is an independent federal agency dedicated to promoting aviation,

railroad, highway, marine, and pipeline safety. Established in 1967, the agency is mandated by Congress through the

Independent Safety Board Act of 1974, to investigate transportation accidents, determine the probable causes of the

accidents, issue safety recommendations, study transportation safety issues, and evaluate the safety effectiveness of

government agencies involved in transportation. The NTSB makes public its actions and decisions through accident

reports, safety studies, special investigation reports, safety recommendations, and statistical reviews.

The NTSB does not assign fault or blame for an accident or incident; rather, as specified by NTSB regulation,

“accident/incident investigations are fact-finding proceedings with no formal issues and no adverse parties … and are

not conducted for the purpose of determining the rights or liabilities of any person” (Title 49 Code of Federal

Regulations section 831.4). Assignment of fault or legal liability is not relevant to the NTSB’s statutory mission to

improve transportation safety by investigating accidents and incidents and issuing safety recommendations. In

addition, statutory language prohibits the admission into evidence or use of any part of an NTSB report related to an

accident in a civil action for damages resulting from a matter mentioned in the report (Title 49 United States Code

section 1154(b)).

For more detailed background information on this report, visit the NTSB investigations website and search for NTSB

accident ID DCA19MM047. Recent publications are available in their entirety on the NTSB website. Other

information about available publications also may be obtained from the website or by contacting—

National Transportation Safety Board

Records Management Division, CIO-40

490 L’Enfant Plaza, SW

Washington, DC 20594

(800) 877-6799 or (202) 314-6551

Copies of NTSB publications may be downloaded at no cost from the National Technical Information Service, at the

National Technical Reports Library search page, using product number PB2020-101011. For additional assistance,

contact—

National Technical Information Service

5301 Shawnee Rd.

Alexandria, VA 22312

(800) 553-6847 or (703) 605-6000

NTIS website

NTSB Marine Accident Report

i

Contents

Contents .......................................................................................................................................... i

Figures and Tables ....................................................................................................................... iii

Acronyms and Abbreviations .......................................................................................................v

Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................... vi

1 Factual Information ..............................................................................................................1

1.1 Background .............................................................................................................................1

1.2 Accident Narrative ..................................................................................................................7

1.3 Search and Rescue ................................................................................................................13

1.4 Injuries ..................................................................................................................................18

1.5 Vessel Information ................................................................................................................20

1.5.1 Applicable Regulations .............................................................................................20

1.5.2 Main Engines and Propulsion ...................................................................................20

1.5.3 Electrical Generation and Distribution .....................................................................20

1.5.4 Air Conditioning System and Ventilation.................................................................23

1.5.5 Auxiliary Systems .....................................................................................................25

1.5.6 Galley Equipment .....................................................................................................26

1.5.7 Maintenance and Repair ...........................................................................................26

1.5.8 Certification, Inspections, and Examinations ...........................................................27

1.6 Accident Damage ..................................................................................................................29

1.7 Operations .............................................................................................................................32

1.7.1 Charter Company ......................................................................................................32

1.7.2 Company Information ...............................................................................................32

1.7.3 Company Loss Control Program ..............................................................................34

1.7.4 Watchstanding...........................................................................................................37

1.8 Survival Factors ....................................................................................................................38

1.8.1 Station Bill ................................................................................................................39

1.8.2 Passenger Manifest and Accountability ....................................................................40

1.8.3 Safety Briefing ..........................................................................................................40

1.8.4 Smoke Detectors and Firefighting Equipment ..........................................................41

1.8.5 Means of Escape and Egress .....................................................................................44

1.8.6 Lifesaving Appliances ..............................................................................................46

1.8.7 Emergency Drills ......................................................................................................47

1.9 Personnel Information ...........................................................................................................48

1.9.1 Crew Recruitment and Training ................................................................................48

1.9.2 Crew Licensing and Certification .............................................................................49

1.9.3 Toxicological Testing ...............................................................................................50

1.10 Waterway Information ..........................................................................................................51

1.11 Meteorological Information ..................................................................................................51

1.12 Postaccident Actions .............................................................................................................51

1.13 Similar Small Passenger Vessel Accidents and Related NTSB Safety Recommendations

Previously Issued ...........................................................................................................................53

NTSB Marine Accident Report

ii

1.13.1 Passenger Ferry Andrew J. Barberi – 2003 ..............................................................53

1.13.2 Passenger Ferry Andrew J. Barberi – 2010 ..............................................................54

1.13.3 Seastreak Wall Street – 2013 ....................................................................................54

1.13.4 Island Lady – 2018....................................................................................................54

1.13.5 Vision – 2018 ............................................................................................................55

1.13.6 Red Sea Aggressor – 2019 ........................................................................................56

2 Analysis ................................................................................................................................57

2.1 General ..................................................................................................................................57

2.2 Exclusions .............................................................................................................................57

2.2.1 Weather .....................................................................................................................57

2.2.2 Alcohol and Other Drugs ..........................................................................................57

2.3 Origins and Potential Sources of the Fire .............................................................................57

2.3.1 Area of Origin ...........................................................................................................58

2.3.2 Ignition ......................................................................................................................60

2.4 Cause of Death ......................................................................................................................62

2.5 Fire Detection........................................................................................................................62

2.6 Roving Patrol ........................................................................................................................65

2.7 Means of Escape ...................................................................................................................67

2.8 Search-and-Rescue Efforts....................................................................................................69

2.9 Oversight ...............................................................................................................................69

3 Conclusions ..........................................................................................................................74

3.1 Findings.................................................................................................................................74

3.2 Probable Cause......................................................................................................................75

4 Recommendations ...............................................................................................................76

4.1 New Recommendations ........................................................................................................76

4.2 Recommendation Reiterated in this Report ..........................................................................77

Appendix A Investigation ............................................................................................................78

Appendix B Consolidated Recommendation Information .......................................................81

Appendix C Small Passenger Vessel Casualty Data Study ......................................................84

References .....................................................................................................................................87

NTSB Marine Accident Report

iii

Figures and Tables

Figure 1. Preaccident photo of Conception .................................................................................... 1

Figure 2. Port side of Conception's salon looking aft .................................................................... 2

Figure 3. Conception simple plan and profile views. .................................................................... 3

Figure 4. Aft main deck of Conception during a previous voyage ................................................ 4

Figure 5. Conception bunkroom arrangement ............................................................................... 5

Figure 6. Vision's and Conception's escape hatches ....................................................................... 6

Figure 7. Conception accident voyage ........................................................................................... 8

Figure 8. Devices charging in Conception's salon. ........................................................................ 9

Figure 9. Conception forward salon windows ............................................................................. 11

Figure 10. Conception on fire ...................................................................................................... 12

Figure 11. Accident site in relation to emergency response assets .............................................. 14

Figure 12. Conception prior to sinking ........................................................................................ 17

Figure 13. Salvaged hull of Conception ....................................................................................... 21

Figure 14. Bunkroom emergency lighting and public address system speaker on Vision ........... 22

Figure 15. Starboard-side main deck of Conception.................................................................... 23

Figure 16. Port side of Conception’s bunkroom. ......................................................................... 24

Figure 17. Truth Aquatics Engine Room Check Log .................................................................. 27

Figure 18. Toilets and stairway to upper deck of Conception ..................................................... 29

Figure 19. Conception wreckage layout at Port Hueneme........................................................... 30

Figure 20. Below-deck areas of Conception ................................................................................ 30

Figure 21. Conception main deck wreckage ................................................................................ 31

Figure 22. Postaccident photo of bunkroom ................................................................................ 32

Figure 23. Power cable for lighting routed through ventilation grille ......................................... 34

Figure 24. Fire at sea emergency instructions .............................................................................. 39

NTSB Marine Accident Report

iv

Figure 25. Truth Aquatics “Welcome Aboard” information ....................................................... 41

Figure 26. Galley of Conception .................................................................................................. 42

Figure 27. Interior view of Conception bunkroom ...................................................................... 43

Figure 28. Staircase from salon leading down to bunkroom ....................................................... 45

Figure 29. Conception bunkroom escape hatch ........................................................................... 45

Figure 30. Conception firefighting equipment, lifesaving appliances, and evacuation plan ....... 46

Figure 31. Postaccident photo of Conception's skiff ................................................................... 47

Figure 32. Postaccident modifications made to Vision ................................................................ 53

Figure 33. Battery charger that caught fire on Vision. ................................................................. 55

Table 1. Initial VHF distress communications between the captain of the Conception and Coast

Guard Sector Los Angeles/Long Beach ........................................................................................ 13

Table 2. VHF communications between Coast Guard Sector Los Angeles/Long Beach and the

Grape Escape ................................................................................................................................ 15

Table 3. Summary of resources assigned in the initial response .................................................. 18

Table 4. Injuries sustained in the Conception accident ................................................................ 19

Table 5. Number of small passenger vessels by initial event type based on the NTSB

classification’s ten most common vessel types ............................................................................. 85

Table 6. Fatalities and injuries by vessel type .............................................................................. 86

NTSB Marine Accident Report

v

Acronyms and Abbreviations

AC alternating current

AIS automatic identification system

ATF Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives

cfm cubic feet per minute

CFR Code of Federal Regulations

COI Certificate of Inspection

CPR cardiopulmonary resuscitation

DC direct current

EMT emergency medical technician

FBI Federal Bureau of Investigation

FRP fiberglass-reinforced plastic

GPS global positioning system

hp horsepower

mph miles per hour

MSD Marine Safety Detachment

MSIB Marine Safety Information Bulletin

NAVTEX Navigational Telex

NBVC Naval Base Ventura County

NTSB National Transportation Safety Board

OCMI Officer in Charge, Marine Inspection

OSC on-scene coordinator

POB persons on board

RB-M response boat-medium

SCC sector command center

SMS safety management system

UMIB Urgent Marine Information Broadcast

VCFD Ventura County Fire Department

VHF very high frequency

NTSB Marine Accident Report

vi

Executive Summary

Accident

About 0314 Pacific daylight time on September 2, 2019, the US Coast Guard received a

distress call from the Conception, a 75-foot-long small passenger vessel operated by Truth

Aquatics, Inc. The vessel was anchored in Platts Harbor on the north side of Santa Cruz Island,

21.5 nautical miles south-southwest of Santa Barbara, California, when it caught fire. When the

fire started, 5 crewmembers were asleep in their bunks in the crew berthing on the upper deck, and

1 crewmember and all 33 passengers were asleep in the bunkroom below. A crewmember sleeping

in an upper deck berth was awakened by a noise and got up to investigate. He saw a “glow” outside.

Realizing that there was a fire rising up from the salon compartment directly below, the

crewmember alerted the four other crewmembers sleeping on the upper deck.

The captain was able to radio a quick distress message to the Coast Guard. Crewmembers

jumped down to the main deck and attempted to access the salon to assist the passengers and

crewmember in a bunkroom below the main deck but were blocked by fire and overwhelmed by

thick smoke. The five surviving crewmembers jumped overboard. Two crewmembers swam to the

stern, re-boarded the vessel, and found the access to the salon through the aft corridor was also

blocked by fire, so, along with the captain who also had swum to the stern, they launched the

vessel’s skiff and picked up the remaining two crewmembers in the water. The crew transferred to

a recreational vessel anchored nearby where the captain continued to radio for help, while two

crewmembers returned to the waters around the burning Conception to search for possible

survivors.

The Coast Guard and other first responder boats began arriving on scene at 0427. Despite

firefighting and search and rescue efforts, the vessel burned to the waterline and sank just after

daybreak, and no survivors were found. Thirty-three passengers and one crewmember died. The

surviving crew were transported to shore, and two were treated for injuries. Loss of the vessel was

estimated at $1.4 million.

Probable Cause

The National Transportation Safety Board determines that the probable cause of the

accident on board the small passenger vessel Conception was the failure of Truth Aquatics, Inc.,

to provide effective oversight of its vessel and crewmember operations, including requirements to

ensure that a roving patrol was maintained, which allowed a fire of unknown cause to grow,

undetected, in the vicinity of the aft salon on the main deck. Contributing to the undetected growth

of the fire was the lack of a United States Coast Guard regulatory requirement for smoke detection

in all accommodation spaces. Contributing to the high loss of life were the inadequate emergency

escape arrangements from the vessel’s bunkroom, as both exited into a compartment that was

engulfed in fire, thereby preventing escape.

Investigative Constraints

The Office of the US Attorney is conducting a criminal investigation of this accident. The

Assistant US Attorney assigned to the case requested the National Transportation Safety Board

(NTSB) not interview the captain of the Conception out of concern that the interview could hinder

the ability of their office to bring criminal charges against the captain. The NTSB obtained

significant information from the other crewmembers; however, the Conception’s captain had many

NTSB Marine Accident Report

vii

years of experience on the same vessel, so the owner and surviving crewmembers referred many

of investigators’ questions to the captain, which remain unanswered. The Office of the US Attorney

also requested that NTSB investigators not interview the first galley hand, who was hospitalized

at the time, or any Truth Aquatics employee responsible for operations.

From September 8 to 10, 2019, the Office of the US Attorney served search warrants on

the offices and two remaining vessels of Truth Aquatics; the NTSB was not invited to participate.

The search warrants resulted in the seizure of thousands of pages of documents and records.

Computers, security camera servers, and items such as fans, smoke detectors, and heat sensors

from each vessel were also seized. Truth Aquatics was not able to provide records or information

to NTSB investigators after the search warrants were executed. Scans of the seized documents and

records were not provided to NTSB investigators until February 2020, and no electronic evidence

recovered from computers and servers was included in the materials provided.

These impediments delayed and complicated the NTSB’s investigation, but they did not

affect its quality, as investigators used the factual information collected to complete an accurate,

safety-focused investigation (see Appendix A for more details on the investigation).

Safety Issues

The safety issues identified in this accident, some of which have been identified in previous

accidents involving passenger vessels, include the following:

• Lack of small passenger vessel regulations requiring smoke detection in all

accommodation spaces. In accordance with the fire safety regulations applicable to the

Conception in Title 46 Code of Federal Regulations Subchapter T, the only compartment

that was required to be fitted with smoke detectors was the passenger bunkroom, since it

was the vessel’s only overnight accommodation space.

1

The Conception was equipped with

two modular smoke detectors in the bunkroom—one mounted on the overhead of each of

the port and starboard aisles. The Conception had no smoke detectors anywhere in the main

deck salon area where crewmembers reported seeing the fire. The nearest heat detector was

well forward in the galley, a deck above the bunkroom, and was not intended to be utilized

as a fire detector for the entire salon. Additionally, all detectors aboard the vessel only

sounded locally. Although the Conception met the regulatory compliance for smoke

detectors in the bunkroom where the passengers and crewmember slept, the fire above them

in the salon would have been well developed before the smoke activated these detectors.

• Lack of a roving patrol. NTSB investigators found that, prior to the accident, the

Conception and other Truth Aquatics vessels were regularly operating in contravention of

the regulations and the vessel’s Certificate of Inspection, which required a roving patrol at

night and while passengers were in their bunks to guard against, and give alarm in case of,

a fire, man overboard, or other dangerous situation. During the investigation, NTSB staff

visited other dive boats operating from Southern California ports and harbors and spoke

with their owners/operators. During informal discussions, all owners/operators stated that

night patrols were assigned whenever passengers were aboard, but the procedures for the

patrols varied greatly. When asked by investigators, Coast Guard inspectors stated that they

1

According to Title 46 Code of Federal Regulations 175.400, accommodation spaces include those spaces used

as a public space, dining room or mess room, lounge or café; overnight accommodation space; or washroom or toilet

space. On board the Conception, the accommodation spaces included the salon, bunkroom, and shower room.

NTSB Marine Accident Report

viii

could not verify compliance with the roving patrol requirement, since inspections were not

conducted during overnight voyages with passengers embarked.

• Small passenger vessel construction regulations for means of escape. The

Conception was designed in accordance with the regulations in Subchapter T in force at

the time of construction. As such, the vessel was required to have at least two emergency

egress pathways from all areas accessible to passengers. The Conception had two means

of escape from the bunkroom: spiral stairs forward and an escape hatch aft, accessible from

either port or starboard aisles by climbing into one of the top aftermost inboard bunks.

However, both paths led to the salon, which was filled with heavy smoke and fire, and the

salon compartment was the only escape path to exterior (weather) decks. Therefore,

because there was fire in the salon, the passengers were trapped, and the crew was not able

to reach them. If regulations had required the escape hatch to exit to a space other than the

salon, optimally directly to the weather deck, the passengers and crewmember in the

bunkroom would have likely been able to escape.

• Ineffective company oversight. During the investigation, the NTSB found several unsafe

practices on company vessels, including a lack of crew training, emergency drills, and the

roving patrol. In reviewing the company’s policies and procedures, along with the Coast

Guard regulations, it is clear that Truth Aquatics had been deviating from required safe

practices for some time. If the company had been actively involved in ensuring the safe

practices required by regulations were enforced, most notably the requirement for a roving

patrol, it is likely this accident would have not happened. Had a safety management system

been in place at Truth Aquatics, it would have likely included procedures for roving patrols

that complied with regulations and a company-involved audit process for identifying and

correcting when non-conformities with the patrol requirements existed.

Findings

1. Weather and sea conditions were not factors in the accident.

2. The use of alcohol or other tested-for drugs by the Conception deck crew was not a factor in

the accident.

3. The origin of the fire on the Conception was likely inside the aft portion of the salon.

4. Although a definitive ignition source cannot be determined, the most likely ignition sources

include the electrical distribution system of the vessel, unattended batteries being charged,

improperly discarded smoking materials, or another undetermined ignition source.

5. The exact timing of the ignition cannot be determined.

6. Most of the victims were awake but could not escape the bunkroom before all were overcome

by smoke inhalation.

7. The fire in the salon on the main deck would have been well developed before the smoke

activated the smoke detectors in the bunkroom.

8. Although the arrangement of detectors aboard the Conception met regulatory requirements,

the lack of smoke detectors in the salon delayed detection and allowed for the growth of the

fire, precluded firefighting and evacuation efforts, and directly led to the high number of

fatalities in the accident.

NTSB Marine Accident Report

ix

9. Interconnected smoke detectors in all accommodation spaces on Subchapter T and

Subchapter K vessels would increase the chance that fires will be detected early enough to

allow for successful firefighting and the evacuation of passengers and crew.

10. The absence of the required roving patrol on the Conception delayed detection and allowed

for the growth of the fire, precluded firefighting and evacuation efforts, and directly led to

the high number of fatalities in the accident.

11. The US Coast Guard does not have an effective means of verifying compliance with roving

patrol requirements for small passenger vessels.

12. The Conception bunkroom’s emergency escape arrangements were inadequate because both

means of escape led to the same space, which was obstructed by a well-developed fire.

13. Subchapter T regulations (Old and New) are not adequate because they allow for primary

and secondary means of escape to exit into the same space, which could result in those paths

being blocked by a single hazard.

14. Although designed in accordance with the applicable regulations, the effectiveness of the

Conception’s bunkroom escape hatch as a means of escape was diminished by the location

of bunks immediately under the hatch.

15. The emergency response by the Coast Guard and municipal responders to the accident was

appropriate but was unable to prevent the loss of life given the rapid growth of the fire at the

time of detection and location of the Conception.

16. Truth Aquatics provided ineffective oversight of its vessels’ operations, which jeopardized

the safety of crewmembers and passengers.

17. Had a safety management system been implemented, Truth Aquatics could have identified

unsafe practices and fire risks on the Conception and taken corrective action before the

accident occurred.

18. Implementing safety management systems on all domestic passenger vessels would further

enhance operators’ ability to achieve a higher standard of safety.

Recommendations

New Recommendations

As a result of its investigation of this accident, the NTSB makes the following ten new safety

recommendations:

To the US Coast Guard

Revise Title 46 Code of Federal Regulations Subchapter T to require that newly

constructed vessels with overnight accommodations have smoke detectors in all

accommodation spaces. (M-20-14)

Revise Title 46 Code of Federal Regulations Subchapter T to require that all vessels

with overnight accommodations currently in service, including those constructed

prior to 1996, have smoke detectors in all accommodation spaces. (M-20-15)

Revise Title 46 Code of Federal Regulations Subchapter T and Subchapter K to

require all vessels with overnight accommodations, including vessels constructed

NTSB Marine Accident Report

x

prior to 1996, have interconnected smoke detectors, such that when one detector

alarms, the remaining detectors also alarm. (M-20-16)

Develop and implement an inspection procedure to verify that small passenger vessel

owners, operators, and charterers are conducting roving patrols as required by Title

46 Code of Federal Regulations Subchapter T. (M-20-17)

Revise Title 46 Code of Federal Regulations Subchapter T to require newly

constructed small passenger vessels with overnight accommodations to provide a

secondary means of escape into a different space than the primary exit so that a single

fire should not affect both escape paths. (M-20-18)

Revise Title 46 Code of Federal Regulations Subchapter T to require all small

passenger vessels with overnight accommodations, including those constructed prior

to 1996, to provide a secondary means of escape into a different space than the

primary exit so that a single fire should not affect both escape paths. (M-20-19)

Review the suitability of Title 46 Code of Federal Regulations Subchapter T

regulations regarding means of escape to ensure there are no obstructions to egress

on small passenger vessels constructed prior to 1996 and modify regulations

accordingly. (M-20-20)

To the Passenger Vessel Association, Sportfishing Association of California, and National

Association of Charterboat Operators

Until the US Coast Guard requires all passenger vessels with overnight

accommodations, including vessels constructed prior to 1996, to have smoke

detectors in all accommodation spaces, share the circumstances of the Conception

accident with your members and encourage your members to voluntarily install

interconnected smoke and fire detectors in all accommodation spaces such that when

one detector alarms, the remaining detectors also alarm. (M-20-21)

Until the US Coast Guard requires small passenger vessels with overnight

accommodations to provide a secondary means of escape into a different space than

the primary exit, share the circumstances of the Conception accident with your

members and encourage your members to voluntarily do so. (M-20-22)

To Truth Aquatics, Inc.

Implement a safety management system for your fleet to improve safety practices

and minimize risk. (M-20-23)

NTSB Marine Accident Report

xi

Recommendation Reiterated in this Report

As a result of its investigation of this accident, the NTSB reiterates Safety Recommendation

M-12-3, which is currently classified as “Open—Unacceptable Response”:

To the US Coast Guard

Require all operators of U.S.-flag passenger vessels to implement SMS, taking into

account the characteristics, methods of operation, and nature of service of these

vessels, and, with respect to ferries, the sizes of the ferry systems within which the

vessels operate. (M-12-3)

NTSB Marine Accident Report

1

1 Factual Information

1.1 Background

Figure 1. Preaccident photograph of the Conception. (Source: www.seawayboats.net)

Owned by the Fritzler Family Trust and operated by Truth Aquatics, Inc. (hereafter referred

to as Truth Aquatics), the 75-foot-long small passenger vessel Conception was constructed in 1981

by Seaway Boats, Inc, in Long Beach, California. The dive vessel was purpose-built to take

recreational divers on one-day and overnight trips to dive sites around the Channel Islands. The

Conception was constructed of fiberglass laid over plywood and had three decks: the upper deck,

main deck, and below deck.

Vessel particulars of the Conception were as follows:

Length: 75 feet

Beam: 26 feet

Draft: 4 feet

Tonnage: 97 gross register tons

Crew: 6

Passenger capacity: 99 (or 46 overnight passengers)

Engine: Two 550-horsepower (hp), 2-stroke, turbo-charged, 92 series, V8 Detroit

Diesel engines

NTSB Marine Accident Report

2

Figure 2. Port side of the Conception's salon looking aft. (Source: M. Ryan)

The Conception’s main deck ran the full length of the vessel, with exterior (open) decks

and an enclosed salon and galley.

2

The salon had food service counters along the centerline and

fixed dining tables on either side. Installed benches along the port and starboard bulkheads

provided seating outboard of the tables, and plastic (outdoor-type) chairs provided seating inboard

of the tables. The galley was forward of the seating area. The center window of three windows on

the forward bulkhead of the galley could be opened from the inside by turning a hand screw and

pushing the window outward at the bottom, since it was hinged at the top. On the forward starboard

side of the salon, two sets of spiral stairways led down below to a shower room (forward) and a

bunkroom (aft). Doors at the aft end of the salon opened to a large, open aft deck. According to

the owner, the doors were always kept open when passengers were on board. There were no other

doors to the exterior from the salon.

2

During interviews, the crew of the Conception referred to the entire salon and galley space as the “galley.” For

clarity, this report will refer to the full space as the “salon,” unless specifically referring to the food preparation area.

NTSB Marine Accident Report

3

Figure 3. Conception simple plan and profile views.

NTSB Marine Accident Report

4

Three small restrooms, each with a single toilet and a small sink, were located just aft of

the salon. Aft of the portside restroom door, a sign posted on the bulkhead identified the location

as the muster area. Exterior walkways on either side of the salon and restrooms extended from the

bow to the aft open deck. Fire hose stations were located on both port and starboard walkways

adjacent to the restrooms (see figure 30 for the location of all firefighting equipment and lifesaving

appliances).

The open deck aft of the salon had a raised platform centerline with racks on either side for

storing scuba tanks and other gear. The raised platform also contained hatches for accessing the

engine room (forward) and lazarette (aft).

3

On the stern of the vessel, a large swim platform

accessible by stairs from the open deck was raised and lowered using an electrically powered

hydraulic winch. When in the raised position, the metal swim platform served as a cradle for a

small outboard-powered inflatable skiff.

Figure 4. Aft main deck of the Conception during a previous voyage. (Source: Profundo no Mundo,

YouTube, annotated by NTSB)

Below the main deck, the vessel was divided into four compartments. The forwardmost

space was an anchor room that was accessible via a small hatch on the forward weather deck. The

shower room was aft of the anchor room, followed by the bunkroom. The bunkroom contained

33 bunks, arranged around 2 aisles, with bunks on either side of each aisle (figure 5). Twelve

double bunks, which allowed two people to sleep in the same bunk, were stacked two-high and

located on the outside of the aisles. One additional double bunk was located underneath the forward

stairway on the starboard side. The remaining 20 bunks were single bunks, with 4 sets of bunks

3

A vessel’s lazarette is its aftermost compartment below the main deck, typically accessed by a deck hatch.

NTSB Marine Accident Report

5

stacked three-high arranged along the centerline, and 2 sets arranged athwartship (across the ship

from side to side) along the aft bulkhead. A two-high set of single bunks was located along the

forward bulkhead on the port side (the upper bunk was reserved for a crewmember). The maximum

occupancy of the bunkroom was 46 persons. Each of the bunks had a privacy curtain that could be

pulled fully across the aisle-accessible side of the bunks.

Figure 5. Conception bunkroom arrangement, with escape hatch location added by NTSB. (Source: Truth

Aquatics; annotated by NTSB)

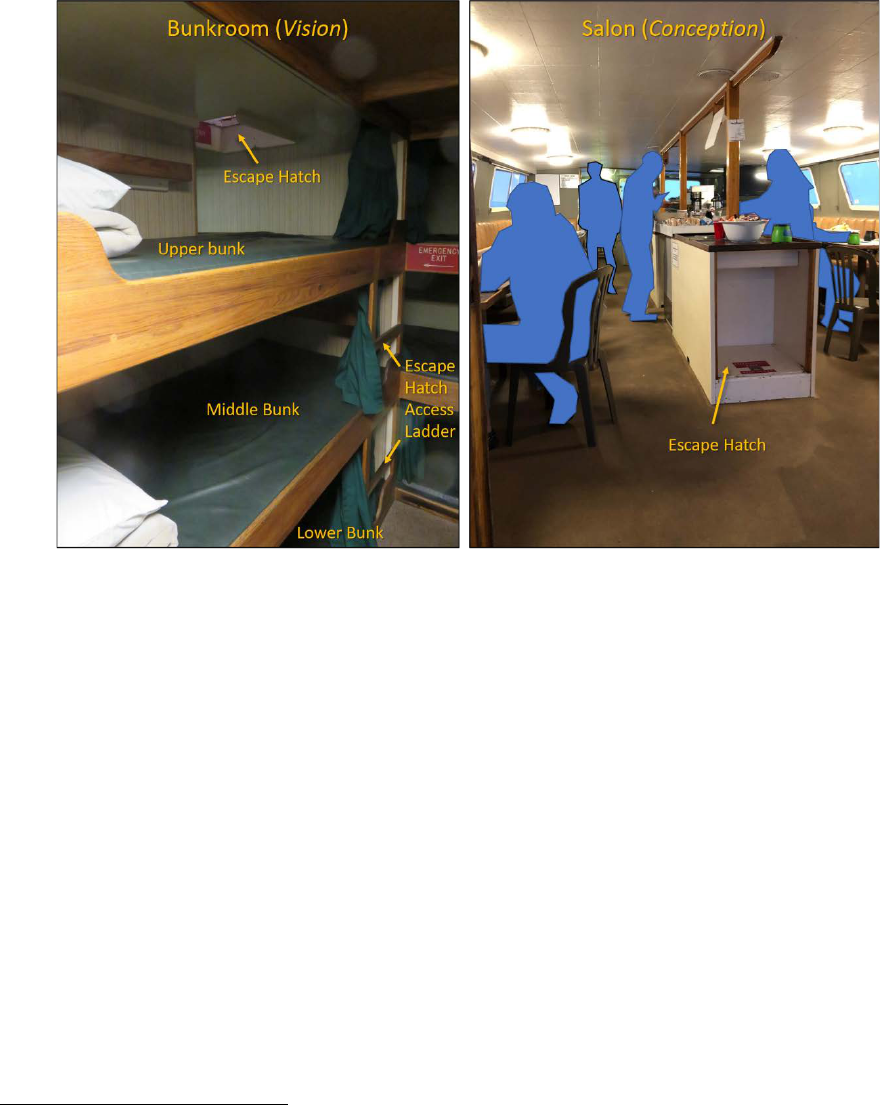

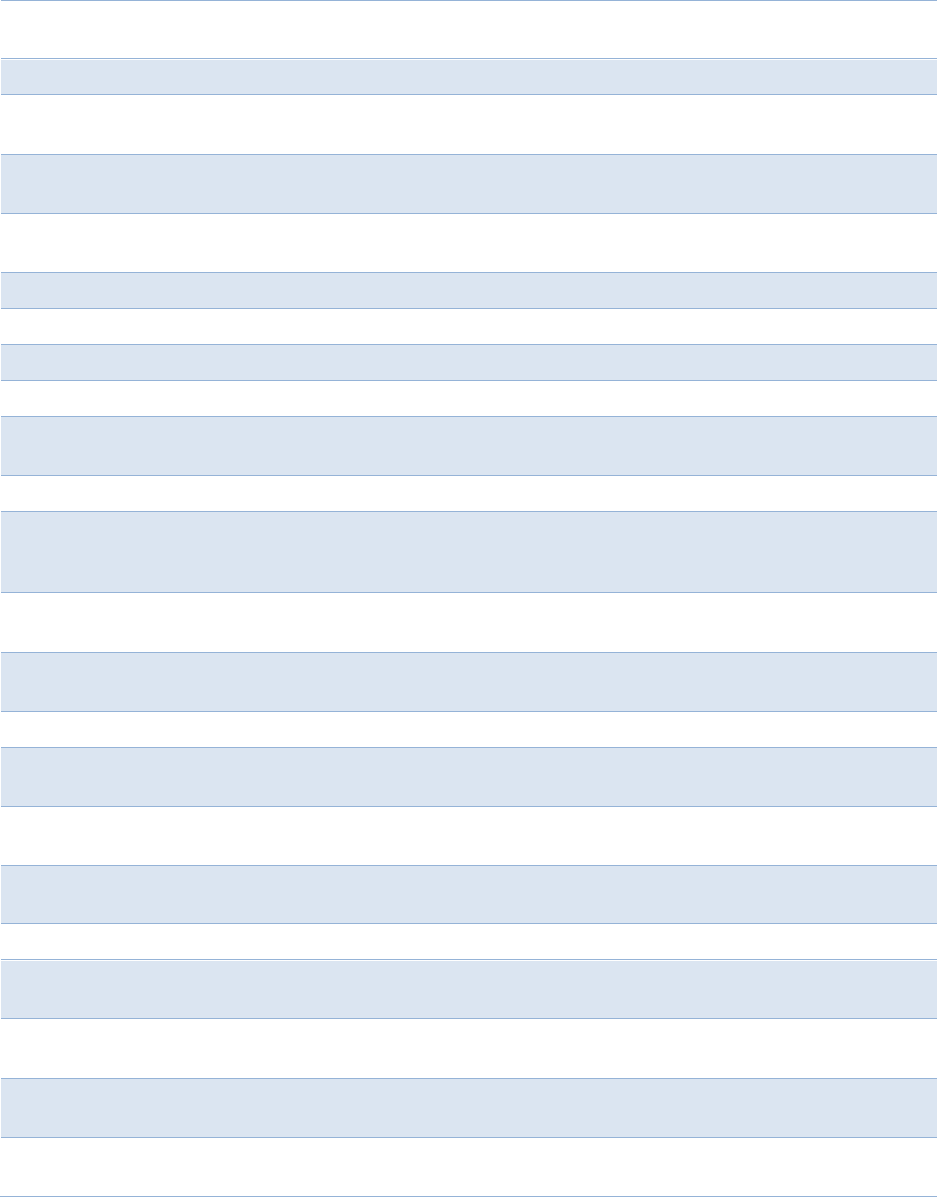

An escape hatch provided an alternate means of exiting the bunkroom (the stairway at the

forward end was the primary means). The escape hatch, which consisted of a removable wooden

panel that was about 22 inches by 22 inches in size, was located in the overhead between the

aftmost centerline bunks.

4

It could be reached from either aisle by climbing a wooden ladder

installed on the side of each centerline aft set of bunks. The hatch exited into the aft end of the

4

The measurements for the escape hatch are from Truth Aquatics’ similar vessel, the Vision, which was built

from the design of the Conception. There was no difference in the design of the escape hatch between both vessels.

NTSB Marine Accident Report

6

salon, and thus both escape routes from the bunkroom exited into the salon. The upper bunks

nearest the emergency escape hatch had passengers assigned to them during the accident voyage.

Figure 6. Photo left is the escape hatch, viewed from the bunkroom, on the Vision, a Truth Aquatics dive

vessel with arrangements nearly the same as the Conception. (Source: NTSB) Photo right, taken during a

previous voyage, shows the escape hatch, viewed from aft in the salon, on the Conception. (Source: J.

Palmer, annotated by NTSB)

A watertight bulkhead divided the bunkroom from the engine room, which contained the

vessel’s two main propulsion engines and a single electrical generator. Fuel tanks that supplied the

engines and generator were located forward in the engine room, outboard of each of the main

propulsion engines. The generator was located aft of the port main propulsion engine. Two air

compressors used for filling scuba diving tanks were mounted aft of the starboard main propulsion

engine. A 40-gallon, 220-volt electric hot water heater was located in the engine room forward of

the starboard main engine.

The lazarette was the aftmost space below the main deck and contained the steering gear

for two rudders, a refrigerator/freezer for storing seafood caught during dives, a clothes dryer, and

a generator/compressor for enriched-oxygen air—commonly referred to as nitrox—used in

diving.

5

The generator produced nitrox on demand and did not store the compressed gas within

the system. (Compressed air and nitrox were stored only in scuba tanks brought on board by

5

Nitrox, with respect to underwater diving, is an air mixture composed of nitrogen and an elevated percentage of

oxygen (when compared to atmospheric air). It is created by passing compressed air through a semi-permeable

membrane, which removes a portion of nitrogen, thus increasing the amount by volume of oxygen in the resultant air

mixture. Typical oxygen percentages used in recreational diving are 32 and 36 percent by volume. Using nitrox-

enriched oxygen air while diving is advantageous because the diver is exposed to less nitrogen and its negative effects.

Divers aboard the Conception paid an extra fee in order to be supplied with nitrox.

NTSB Marine Accident Report

7

passengers and secured in the outer main deck racks.) In addition to the mechanical equipment,

wet suits were dried and stored in the lazarette.

On the upper deck, the Conception’s wheelhouse sat atop the forward end of the salon. In

addition to controls for the engines and rudders, the wheelhouse contained radar and depth sounder

displays, global positioning system (GPS) receivers, a very high frequency (VHF) radio, and an

electronic charting system. Two crew bunks with privacy curtains were installed at the back of the

wheelhouse. A short passageway led aft from the wheelhouse to a door out to the sun deck. Two

small crew staterooms were located on either side of the passageway; the portside room contained

two crew bunks, and the starboard side room held a single bunk. A small shower room on the

starboard side aft was also accessed from the passageway. The sun deck contained benches and

large boxes for storing the vessel’s lifejackets and life floats, and there were two additional life

floats on top of the wheelhouse.

6

A single staircase on the starboard side of the sun deck, aft,

provided access between the main deck and the sun deck.

1.2 Accident Narrative

The Conception had been chartered by Worldwide Diving Adventures, Inc., a scuba diving

tour, instruction, and guide company, to take a group of 33 passengers on a 3-day dive trip to

locations around the Channel Islands, California, over the 2019 Labor Day weekend. The voyage

was scheduled to get under way from Santa Barbara, California, at 0400 on Saturday, August 31,

and return by 1700 on Monday, September 2. Truth Aquatics encouraged customers to board the

vessel the night before early morning departures, and passengers for the accident voyage began

arriving in the evening on August 30, embarking via the main deck. Per Truth Aquatics’ website

and the company’s General Information Handbook, passengers were instructed to sign a posted

manifest upon boarding, store their gear, and then proceed to their bunks below deck.

7

On the accident voyage, all bunks had assigned occupants, except for numbers 7U, 9L,

24U, and 26L (these were the upper and lower bunks of the three-high single bunks running

athwartships on the aft bulkhead). Four of the ten double bunks were occupied with two

passengers; the remaining double bunks had a single occupant. A Conception deckhand told

investigators that passengers on the accident voyage kept to the posted sleeping arrangements.

According to the deckhand, luggage was stowed below some of the bunks and above them, in a

designated area, and the aisles between the bunks were clear of luggage at all times. Some

passengers kept personal items and effects, such as purses and backpacks, with them in their bunk

spaces.

The second captain (mate) was the first of the vessel’s six crewmembers to arrive at the

Conception, embarking sometime between 2200 and 2300.

8

The first and second galley hands were

next to arrive, boarding separately between 2300 and midnight. They each told investigators that

after boarding, they went to their bunks on the upper deck and went to sleep. The first deckhand

stated that he and the second deckhand arrived at the vessel at 0320 the next morning, and,

according to crewmembers interviewed after the accident, the captain boarded about 10 minutes

6

Life floats are buoyant primary lifesaving devices designed to support a number of persons partially immersed

in the water, unlike life rafts that keep people completely out of the water.

7

According to crewmembers, passenger bunks were generally assigned by the charterer.

8

The vessel was required to have a credentialed master and mate, although there is no mate’s credential for

vessels of this size. “Second captain” was the term used by Truth Aquatics and the Conception crew in lieu of mate.

NTSB Marine Accident Report

8

later.

9

Once on board, the deck crew began conducting pre-underway checks of the vessel’s

equipment. The generator was then started and shore power removed, a visual inspection of the

bilges was performed, and the main engines were started and tested. The deckhands cast off lines,

and, according to the vessel’s automatic identification system (AIS), the Conception was under

way at 0404 outbound from Santa Barbara Harbor.

10

The captain took the helm for the outbound

voyage, while the rest of the crew went to sleep until about 0600.

During Truth Aquatics’ dive trips, the destinations were at the discretion of the captain and

based on weather conditions and the charterer’s preferences. For this voyage, the captain of the

Conception chose to head toward Santa Cruz Island, which provided dive sites that were protected

from moderate-to-high winds in the area. The vessel transited to the south side of the island and

anchored at a dive site near Albert Anchorage at 0830 that morning. Once anchored, the passengers

gathered in the salon to eat breakfast and listen to a safety brief.

Figure 7. Conception accident voyage reconstructed from AIS data, with selected diving and anchoring

sites at Santa Cruz Island. (Background source: Google Earth)

The standard safety brief included information on the lifejackets and other lifesaving

equipment, escape routes from the passenger bunkroom and salon, the location for mustering in

the event of an emergency, and dive safety information. During the accident voyage, the safety

briefing, which was being conducted by the first deckhand, was interrupted when a passenger

9

The agency’s investigation of this accident was conducted in parallel with the Office of the US Attorney’s

ongoing criminal investigation. The criminal investigation resulted in the NTSB having limited access to key

personnel of Truth Aquatics working at the time of the accident, including the captain of the Conception, the first

galley hand, or any employee responsible for operations. While on scene, investigators interviewed the remaining

surviving Conception crewmembers; the owner of Truth Aquatics, former Truth Aquatics crewmembers, passengers,

contractors, and service providers; and several first responders. See Appendix A

for more details regarding the

investigation.

10

AIS is a maritime navigation safety communications system. At 2- to 12‑second intervals on a moving vessel,

the AIS automatically transmits vessel information, including the vessel’s name, type, position, course, speed,

navigational status, and other safety‑related information, to appropriately equipped shore stations, other vessels, and

aircraft. The rate at which the AIS information is updated depends on vessel speed and whether the vessel is changing

course. AIS also automatically receives information from similarly equipped vessels.

NTSB Marine Accident Report

9

fainted. After the passenger was revived and his vital signs checked, the remainder of the safety

brief was conducted by the captain, who, according to the deckhand, provided “an abridged

version” of the dive safety section of the brief.

Over the next two days, the Conception transited between sites around Santa Cruz Island,

anchoring at each location to allow the passengers to dive. The vessel spent the first night anchored

at Smugglers Cove on the eastern side of the island. The next day, Sunday, September 1, the vessel

transited to various dive sites on the north side of the island.

Between 2030 and 2130, seventeen divers conducted a night dive at a location known as

Quail Rock on the northwest side of the island. While the divers were in the water, the second

galley hand opened the electrical circuit breakers for the galley burners and griddle. (He told

investigators that this had been the normal practice each night, ever since a burner had been left

on inadvertently on a previous voyage.) He also closed the circuit breakers for the air conditioning

unit to allow the bunkroom to cool before the passengers went to sleep.

Once the divers were back on board,

the flashlights and cameras that they used

during the dive were stowed on the two aft

tables in the salon. During interviews,

crewmembers stated that some of these

electronics, along with cell phones and tablets,

were plugged in to recharge via 110-volt

alternating current (AC) receptacle outlets

located between the bench seat padding and on

the aft bulkhead (figure 8). Crewmembers

remembered seeing at least one passenger-

owned power strip being used to recharge the

electronics.

After the night dive, the Conception

relocated to Platts Harbor, a natural,

semi-protected anchorage to the east of

Quail Rock, to anchor for the night. The

second captain remembered seeing a large

sportfishing boat (later identified as the

Grape Escape) in the anchorage when the

dive boat arrived about 2300. According to the

second captain, the crew conducted a

walkthrough of the main deck to check for trip

hazards and to stow loose gear. The doors to

the salon remained open, as they always were when passengers were on board. Sometime before

midnight, each of the crewmembers went to bed: the second deckhand slept in the passenger

bunkroom, and the other crewmembers slept in berths on the upper deck. Crewmembers reported

that a few passengers were still awake when they left the salon to head to their berthing. There

were no crewmembers assigned to monitor the position of the Conception while it rode at anchor

(according to the second captain, there was an alarm in vessel’s wheelhouse to notify the crew if

the anchor was dragging).

Figure 8. Photo taken during accident voyage

(August 31, 2019) of devices plugged in to charge

at the port side aft corner of the salon on the

Conception. (Source: J. Dignam).

NTSB Marine Accident Report

10

According to the second galley hand, he woke up about 0130 on Monday, and, as was his

usual practice when he awoke in the middle of the night, he went down to the galley to collect and

wash any used coffee cups and other dishes and to conduct general cleaning. He told investigators

that there were no passengers or crew awake or in the salon at the time he was working in the

galley. After cleaning up, he used one of the restrooms on the aft main deck and went to his bunk

on the upper deck to go back to sleep. He stated that as he came out of the restroom, he looked up

at a wall clock and noted that it was 0235.

Sometime later, the second galley hand was awoken by the sound of what he thought was

a plastic chair sliding on the salon deck. He stated that then he heard a noise that “sounded like

someone fell.” He considered getting up, concerned that a person might be injured, but then heard

what he thought to be the sound of the restroom door shutting. He continued to lay in his bunk,

and next heard what he thought was a person yelling, “ahhh!” The second galley hand got out of

his bunk to go check on the person and, looking out through the door to the sun deck, saw a yellow

glow emanating from the main deck below the aft starboard side of the sun deck. Realizing what

he was seeing, the second galley hand turned around and yelled “fire! fire!” to wake up the four

other crewmembers sleeping on the upper deck.

The first galley hand told investigators that he had heard “a pop, and then a crackle

downstairs.” He then heard the second galley hand jump down from his bunk, and shortly

thereafter yell, “fire!”

After warning the crew, the second galley hand ran to the staircase at the aft end of the sun

deck to attempt to get down to the main deck. He stated that when he reached the staircase and

looked down, the restroom at the bottom of the staircase was on fire, and flames blocked the way

down. He returned to the upper deck stateroom area, told the other crewmembers that the way was

blocked, and then proceeded to the port side of the sun deck. There, he climbed over the railing

and lowered himself down onto the main deck.

The second galley hand stated that he ran back to the open deck, intending to enter the

salon through the open rear doors to retrieve fire extinguishers. However, he could not get into the

salon because the entire entryway was on fire. He told investigators that the area where the

bunkroom escape hatch was located was engulfed in flames and was not visible, and the fiberglass

on the ceiling of the entryway to the salon was melting and dripping down. He said that he ran aft

toward the stern, but, realizing there was nothing that he could do there, he turned around again.

The second captain and first deckhand slept in the bunks in the wheelhouse, and when

awakened by the second galley hand, they had both proceeded aft toward the door to the sun deck

and saw the flames on the aft starboard side. They were met at the door by the second galley hand,

who told them that the staircase to the main deck was blocked. Returning to the wheelhouse, the

second captain and the first deckhand were instructed by the captain to lower themselves to the

main deck via the wheelhouse wing stations. In a statement to investigators, the captain wrote that

he opened the wing station doors on either side of the wheelhouse.

The second captain exited through the wing station door on the port side and lowered

himself down to the main deck. From there, he looked to go aft, but he said that the exterior

passageway was blocked by smoke and flames emanating from the salon windows. He stated that

he proceeded forward and opened the bow gate on the port side, reasoning that if passengers could

escape the bunkroom and get to the main deck bow, they would be able to more easily evacuate

through the open gate.

NTSB Marine Accident Report

11

From the aft deck, the second galley hand saw a crewmember lowering himself down to

the main deck, so he ran forward through the smoke along the port exterior passageway. About the

same time, the first galley hand was attempting to jump down to the main deck from the port

wheelhouse wing station. The first galley hand told investigators that he misjudged the distance to

the deck and landed with all his weight on his left leg, breaking his leg as he hit the deck. He

landed in front of the second galley hand, who leapt over him and continued forward to the bow.

The first deckhand had also exited the wheelhouse via the port wing station. Once on the

main deck, he looked aft and saw that the port exterior passageway was blocked by smoke and

flames coming out of the salon windows and wrapping around the sun deck above. He proceeded

to the bow and tried to open the center window on the forward bulkhead of the salon, which looked

into the galley area, in an attempt to reach the passengers. The center window was the only window

on the front of the salon that was designed to open, but it was secured from the inside by threaded

knobs (it was not a designated emergency exit). The deckhand, aided by the second galley hand,

struggled to pry the window open, but could not. The two crewmembers told investigators that the

window was warm, but not hot, and when they looked through the window, the view was

completely obscured by thick, black smoke.

Figure 9. Preaccident photo of Conception forward salon windows. In this photo, the center window is open.

However, during the accident, the window was closed and secured as the crew attempted to access the

space. The port and starboard windows were not designed to be opened. (Source: T. Thompson)

During this time, the captain was in the wheelhouse making a distress call over VHF radio.

At 0314, he transmitted, “Mayday, Mayday, Mayday. Conception, Platts Harbor, north side Santa

Cruz.” When Coast Guard Sector Los Angeles/Long Beach watchstanders responded to the distress

call, the captain transmitted, “39 P-O-B. I can’t breathe. 39 P-O-B. Platts.” The smoke filling the

wheelhouse then forced the captain out of the space, and he jumped into the water from the

starboard side wheelhouse wing station.

As the first deckhand continued to try to open the forward salon window, he remembered

a fire axe mounted in the wheelhouse. He looked up to the wheelhouse and was about to yell to

the captain to get the axe when he and the second captain saw the captain leap into the water. As

the captain jumped, smoke followed him down to the water. Both the first deckhand and the second

captain believed the captain was on fire as he jumped. Consequently, the second captain dove into

the water on the starboard side to attend to the captain.

NTSB Marine Accident Report

12

Attempting to find another way to reach passengers, the first deckhand opened the anchor

locker hatch on the bow. Looking inside, he saw that there was no access aft to the shower room

and bunkroom below, and there was no smoke in the space at the time. He then checked the port

and starboard exterior passageways, and both were blocked by smoke and flames.

According to the first deckhand, the captain then told the remaining three crew on the bow

to jump into the water. The first galley hand was in a great deal of pain due to his broken leg, but

he eventually entered the water through the port bow gate. The second galley hand and the first

deckhand also entered the water. The first and second galley hand then swam away from the vessel,

while the first deckhand swam toward the stern.

After finding that the captain was unharmed, the second captain swam to the stern and re-

boarded the Conception via the vessel’s swim platform, which was in the raised position with the

inflatable skiff stowed on it. He proceeded up onto the open main deck and toward the salon, where

he found that the entire deckhouse was being consumed by fire. He said that he “could see the aft

escape was fully engulfed in flames.” He stated that he opened the engine room hatch but was

blocked from entering by black smoke, though he did not see flames.

The second captain’s next thought was to launch the skiff so that the crew could pick up

any survivors that had made it off the Conception. He stated that as he proceeded aft, he noted that

the lights were still on in the lazarette (the hatch was normally left open), so he knew that the

vessel still had electrical power. He energized the hydraulic pump for the winch that raised and

lowered the swim platform and prepared to lower the skiff into the water. By this time, the first

deckhand had also climbed up on the stern of the Conception, and he assisted the second captain

in launching the skiff.

Once the boat was in the water, the second captain assisted

the captain, who had swum to the stern of the Conception, into the

boat. Meanwhile, the first deckhand went up onto the back deck

of the dive boat to once again look for a way to help any

passengers. The fire had continued to consume the vessel, and he

found no way to get into the salon or to the bunkroom below. The

fire also prevented the deckhand from accessing the fire hose and

the fire pump remote start control, which were located on the port

side of the vessel. He next attempted to reach the fire pump in the

engine room but was prevented from entering the space due to

smoke at the hatchway. (He also reported seeing no flames in the

engine room.) The captain yelled at him to get in the skiff, so he

went aft and boarded the small boat.

After the three crewmembers got the engine on the skiff

running, they drove to where the two galley hands had swum away

from the Conception and helped both into the boat. The first

deckhand then took the controls and drove the skiff over to the

anchored sportfishing boat Grape Escape. When they arrived at

the vessel, the crewmembers yelled and banged on the hull and

back door to the salon until the Grape Escape’s owners were

awakened. The Grape Escape owners described their first sight of

the Conception as “completely on fire from one end to the other. It

was already completely engulfed. There wasn’t a spot on that boat

Figure 10. Cell phone photo of

Conc

eption

on fire, taken from

sportfish

ing boat Grape Escape

.

(Source: S. Hansen)

NTSB Marine Accident Report

13

that wasn’t on fire.” One of the owners then took the captain and second captain up to the

wheelhouse to make radio calls to the Coast Guard shortly before 0329, while the other owner

assisted the remaining crewmembers. The first deckhand and second galley hand assisted the

injured first galley hand onto the Grape Escape.

1.3 Search and Rescue

The Coast Guard Sector Los Angeles/Long Beach Command Center (SCC), located in San

Pedro, California, maintained command, control, and communications for Coast Guard operations

in the area. The SCC received the Conception’s initial distress call by VHF radio at 0314:23. The

SCC made repeated call-outs, which went unanswered after the crew abandoned the vessel. Using

the VHF radio direction finder, the SCC was able to estimate the vessel’s position and issued an

Urgent Marine Information Broadcast (UMIB) at 0322:54.

11

Table 1. Initial VHF distress communications between the captain of the Conception and Coast Guard

Sector Los Angeles/Long Beach.

Time

(PDT)

Originator Message

03:14:23 Conception Mayday, mayday, mayday! Conception. Platts Harbor, north side Santa

Cruz. Help.

03:14:34 Coast Guard Vessel under distress, this is Coast Guard Sector Los Angeles on Channel

one-six. What is your position and number of persons on board? Over.

03:14:42 Conception [unintelligible] three-nine P-O-B. I can't breathe.

Three-nine P-O-B. Platts.

03:14:54 Coast Guard Vessel in distress, Coast Guard Sector Los Angeles. Roger. You have 29

persons on

board and you can't breathe. What is your current GPS

position? Over.

03:15:20 Coast Guard Vessel in distress, Coast Guard Sector Los Angeles on Channel one-six.

What is your GPS position? Over.

03:16:06 Coast Guard Vessel in distress, Coast Guard Sector Los Angeles on Channel one-six.

The SCC then telephoned Coast Guard Station Channel Islands Harbor at 0323 and

requested that they proceed to the scene for a medical emergency, based on the Conception

captain’s transmission of “I can’t breathe.”

12

While the crew prepared to get under way, the

Station’s Officer of the Day called the Ventura County Fire Department dispatch by radio to request

support (at least one paramedic and advanced life support equipment) to get under way with them.

At 0324, the SCC requested Coast Guard air assets located at Naval Base Ventura County (NBVC)

Point Magu conduct search and rescue. The SCC also directed the Coast Guard cutter Narwhal,

which was 5 hours away, about 6.5 miles southeast of Long Beach and already under way, to

proceed to the accident location.

13

11

An Urgent Marine Information Broadcast (UMIB) is a request for assistance from any available mariners. It is

broadcasted on VHF Channel 16 and by Navigational Telex (NAVTEX).

12

Unless otherwise noted, “Station” in this report refers to Coast Guard Station Channel Islands Harbor.

13

USCGC Narwhal (WPB87335) was an 87-foot patrol boat homeported in Corona Del Mar, California.

NTSB Marine Accident Report

14

Figure 11. The accident site in relation to emergency response assets. The red triangle marks the site of

the Conception fire. (Background: Google Maps)

At 0329, the owner of the Grape Escape called the Coast Guard on VHF radio, stating “We

have a Mayday. I have a commercial boat on fire. Santa Cruz Island.” This was the first notification

to the Coast Guard that the nature of the distress was a fire. He gave the position of the vessel, and

then the second captain got on the radio and reported to the Coast Guard that there were “33 souls”

trapped in the bunkroom.

14

The Conception captain took over the radio from the second captain

and explained the situation in more detail to the SCC.

The second captain and first deckhand next re-boarded the skiff to go search for survivors,

while the two galley hands and the captain remained on the Grape Escape. The second captain

stated that while the skiff circled the burning Conception, he and the first deckhand heard several

“explosions.” The crew did not locate any survivors, and they returned to the Grape Escape. Later,

at the SCC’s request, they made additional searches, also without success.

14

The SCC watchstander misheard the Conception captain say the passengers were “locked” below deck when

they were actually “blocked” by fire. The second captain mistakenly omitted the missing crewmember in his initial

report by radio, stating there were “33 souls” still aboard.

NTSB Marine Accident Report

15

Table 2. VHF communications between Coast Guard Sector Los Angeles/Long Beach and the Grape

Escape.

Time

(PDT)

Originator Message

03:29:30 Grape Escape Pan-Pan, Pan-Pan, Coast Guard, Coast Guard.

03:29:35 Coast Guard

Vessel Conception, Coast Guard Sector Los Angeles on Channel

one-six. Over.

03:29:39 Grape Escape This is a -- actually it's a mayday. I have a commercial boat on fire.

It's on Santa Cruz Island at ah --

03:29:57 Coast Guard Vessel hailing Coast Guard Sector Los Angeles, come back or say

again your last. Couldn't understand it. Over.

03:30:05 Grape Escape We're at Platts Harbor on Santa Cruz Island.

03:30:12 Coast Guard Say again the harbor name. Over.

03:30:17 Grape Escape Platts Harbor. Platts Harbor.

03:30:20 Coast Guard Roger, Captain. What is the, what is the emergency? Over.

03:30:30 Coast Guard

Vessel Conception, Coast Guard Los Angeles. What is the

emergency? Over.

03:30:35 Grape Escape Hang on just a second.

03:30:40 Conception second

captain on Grape

Escape

Hello. This is crew of Conception. Our boat is on fire. We are on a

neighboring vessel. We have 33 souls on board down below trapped

in the bunkroom. We cannot evacuate them off the vessel.

03:30:57 Coast Guard Vessel reporting a vessel on fire. Roger, Captain. Your vessel is on

fire; is that correct?

03:31:07 Conception Second

Captain

The vessel's on fire, the vessel's name is Conception.

03:31:10 Coast Guard Roger. Are you on board the Conception?

03:31:13 Conception Second

Captain

We're on board a neighboring vessel. We abandoned ship.

03:31:19 Coast Guard Roger. And there's 33 people on board the vessel that's on fire; they

can't get off?

03:31:24 Conception Second

Captain

That is correct.

03:31:27 Coast Guard Roger. Are they locked inside the boat?

03:31:32

Conception Second

Captain

That’s correct, sir.

03:31:37 Coast Guard Roger. Can you get back on board and unlock the boat or unlock the

doors so they can get off?

03:31:43 Conception Second

Captain

Every escape path was on fire.

03:31:48 Coast Guard Roger. You

don’t have any firefighting gear at all? No fire

extinguishers or anything?

NTSB Marine Accident Report

16

Time

(PDT)

Originator Message

03:32:05 Conception Captain [The captain relieved the second captain on the radio.] Coast Guard

Sector LA, we could not get to the bunkroom. The fire absorbed the

wheelhouse and --

03:32:26 Coast Guard Roger, that. Is this the captain of the Conception?

03:32:30 Conception Captain

Yes. My name is [redacted]. I got one mayday out. Smoke, in the

wheelhouse there was flames at the back door and the side door. We

had to jump from the wheelhouse off the boat.

03:32:59 Coast Guard Roger. Was that all the crew that jumped off?

03:33:04 Conception Captain Five of the crew from the wheelhouse jumped out. One crew is down

in the bunkroom. Thirty-four people still on board, okay?

03:33:22 Coast Guard Roger. Is the vessel fully engulfed right now?

03:33:26 Conception Captain To the deck. Fully engulfed to the deck.

At 0335, the SCC broadcast another UMIB with the name and position of the vessel and

indicating that the vessel was on fire. The crew at Coast Guard Station Channel Islands Harbor

overheard the radio conversation between the Conception crew on board the Grape Escape and

the SCC, and between 0342 and 0349, they launched two 45-foot response boats-medium (RB-

Ms). At 0343, the Ventura County Fire Department (VCFD) Engine 53 company captain requested

an additional engine company respond aboard Channel Islands Harbor Patrol Boat 15, a 32-foot

fire boat jointly operated with the VCFD.

Channel Islands Harbor Patrol overheard the Coast Guard radio traffic on both VHF and

VCFD frequencies, retrieved the Conception’s AIS position from an online source, and

immediately prepared its Boat 15 to respond once an engine company arrived. Boat 15 was under

way with the crew of Engine 54 at 0404 (Ventura City Harbor Patrol’s fireboat, Boat 1, later got

under way, with Engine 26, at 0448).

Multiple additional agencies responded to the Coast Guard Channel Islands Station, where

an Incident Command Post was set up at 0358.

15

The first Coast Guard RB-M arrived on scene at 0427 after travelling 27 miles and crossing

the channel through conditions of reduced visibility; they found the Conception completely

engulfed in flames and began searching for survivors. The second Coast Guard RB-M, with VCFD

Engine 53 embarked, arrived on scene immediately after and assumed the role of on-scene

coordinator (OSC).

16

Two firefighters (a paramedic and an emergency medical technician [EMT])

from the second RB-M boarded the Grape Escape to assess the injured Conception crewmembers,

and then the boat began searching the area for any other survivors.

15

Agencies responding to Coast Guard Channel Islands Station included the VCFD, Channel Islands Harbor

Patrol, Ventura County Sheriff’s Department, VCFD Public Affairs, Ventura County Coroner’s Office, Channel

Islands Parks Service, and the owner of the Conception.

16

The on-scene coordinator is the designated vessel or aircraft assigned to coordinate the activities of all

participating search units.

NTSB Marine Accident Report

17

Each RB-M was equipped with a P6 portable dewatering pump, which was the only

equipment that could be used for firefighting.

17

Since Boat 15 was en route with more pump

capacity and the firefighting foam required to fight a fire of this size, the two RB-Ms searched for

survivors in the water, deeming it a higher priority after concluding that there were likely no

survivors in the wreck given the mass conflagration.

A Coast Guard helicopter arrived on scene about the same time as the Coast Guard RB-Ms.

When the paramedic and EMT from the RB-M had boarded the Grape Escape, they determined

that the first galley hand needed to be evacuated. However, due to the risk of entanglement with

the rescue litter and the Grape Escape’s rigging, the Engine 53 crew determined that it was safer

to leave the injured crewmembers on the Grape Escape rather than transfer them to the helicopter.