Association of Women Surgeons

Pocket Mentor

A Manual for Surgeons in Training

and Medical Students

Fifth Edition

2013

Association of Women Surgeons

E-mail: [email protected]

Website: www.WomenSurgeons.org

1

POCKET MENTOR

Fifth Edition

Annesley Copeland MD, FACS

This edition was prepared with

input from many individuals.

Special thanks to the AWS Resident

and Medical Student Committees for

their thoughtful insights and contributions.

Fourth Edition

Mary Hooks MD, MBA, FACS

Third Edition

Danielle Walsh MD, FACS

First and Second Editions

Joyce Majure MD, FACS

Published by the

Association of Women Surgeons

WomenSurgeons.org

© 2013 The Association of Women Surgeons. All rights reserved. This book and all its contents are protected by

copyright. No part of it may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any

means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher.

Made in the United States of America.

2

The Association of Women Surgeons, founded in 1981, is an organization whose

mission is to inspire, encourage, and enable women surgeons to realize their

professional and personal goals. This publication represents two of our goals:

advancing

the highest standards of competence

, and

promoting professional growth and

development

. At the time the first edition was written, there was a very small number

of women faculty in most Departments of Surgery, and many women residents found it

difficult to identify appropriate role models and advisors to facilitate their surgical

education. The first three editions were therefore written primarily for women students

and residents. Over the years the wisdom contained in this publication has become a

resource for both male and female trainees, and the fourth edition was intentionally

gender-neutral. With this, the fifth edition of this publication, we have updated and

expanded the information and advice contained herein. We expect that all surgical

residents as well as medical students will find this book to be a valuable resource. It is

the intent of this book to provide practical information and advice, which we believe will

make your surgical training experience more rewarding. We hope it will help you

improve communication with your peers and attendings and inspire you to develop

confidence in your skills and abilities. We encourage those who derive benefit from this

publication to pass along the wisdom and share it with colleagues. We would like to

invite all who have benefited from this publication to join our organization.

3

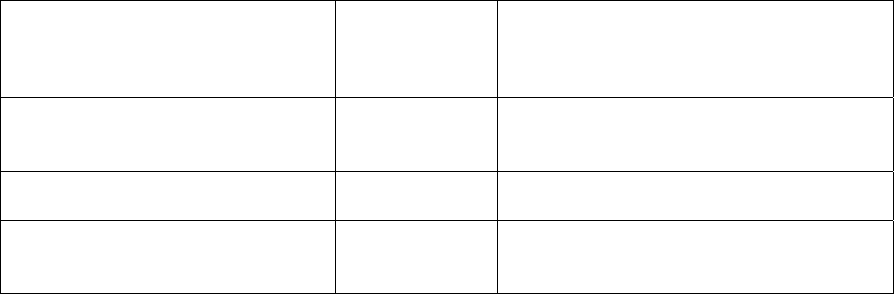

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Preface……........................................................................................................1

Introduction......................................................................................................2

Chapter 1: Learning to be a Surgeon ...............................................................5

Professional Behavior

Knowledge and Patient Care

Making Decisions

Rounds

Presentations

Call

References

Chapter 2: Getting The Work Done ................................................................17

Internship

Junior Resident

Chief Resident

Residency Calendar

References

Chapter 3: In the Operating Room ................................................................26

Technical Skills

Operating Room Strategies

When a Case Is Not Going Well

References

Chapter 4: Care and Feeding of Your Surgical Education ..............................32

Core Competencies

Seeking and Using Feedback

ABSITE

Who’s Who in the Hierarchy

Mentors

References

Chapter 5: Problems and Pitfalls ...................................................................41

When You Make a Mistake

When a Patient Does Badly

Substance Abuse

Discrimination

Sexual Harassment

Reproductive Issues

Personal Relationships

4

Conflict Resolution

Resident Rights

If you Think You Want to Quit

References

Chapter 6: Taking Care of Yourself.................................................................54

Basics of Self-Preservation

Locker List

Life Balance

Occupational Hazards

Maintaining Relationships Outside the Hospital

References

Chapter 7: Directing Your Future....................................................................59

Research Experience

Non-traditional Experience

Fellowships

Board Certification

Practice Options

References

Chapter 8: For the Medical Student ...............................................................74

Introduction

The Junior Surgery Clerkship

Fourth Year Concerns

FAQs for Medical Students

Appendix.........................................................................................................85

Electronic Resources and References

ABSITE Resources

Surgical Bibliography

Quotes...........................................................................................................105

5

Chapter 1: LEARNING TO BE A SURGEON

PROFESSIONAL BEHAVIOR AND APPEARANCE

Appearance

Attendings, residents, nurses, and patients will be forming an opinion of you as a doctor

and as a coworker. You must learn to be professional and businesslike in your affect

and attire if you expect to be taken seriously as a surgeon. Begin with always being

clean, neat, well-groomed, and dressed in a professional and practical manner. Find out

exactly what the customary attire is for each institution participating in your particular

program. In some institutions, for example, scrubs are only to be worn in the operating

room (OR) or on call, but not on rounds, in clinic, or at conference. In other programs,

everyone wears scrubs most of the time. Some ORs have strict policies regarding the

wearing of jewelry in the OR, so check with the OR supervisor. Many programs will

have specific dress codes. Dress codes for men generally run to the collared shirt and

tie, which is easy enough to adhere to. Dress codes for women tend to be less specific,

and it may be more difficult to decide what is within the norm. Do not wear anything

that can remotely be considered seductive. Avoid short skirts, half shirts, low necklines,

sheer fabrics, dangling earrings and anything tight. Fingernails must be clean, and

trimmed or filed short. Comfortable shoes are a must in and outside the OR. Open-toe

shoes in clinic may be both a health hazard and prohibited in your institution. It is

possible to have style and flair – and dress like a professional. Ours is generally a

conservative profession; leave the green hair dye and glitter nail polish to your time off.

If in doubt, use this good rule of thumb: dress the part of the surgeon whom your

grandmother would be at ease to see as her surgeon. You can be yourself, but be

comfortable, and be practical. Remember that during the course of a day, you may be

seeing patients in clinic, pulling chest tubes, and helping out with a fresh trauma in the

Emergency Department (ED). Take this into consideration when dressing for the day.

NEVER continue to wear your white coat, shoes, scrubs, or any article of clothing if it is

visibly soiled by blood or other body fluids. It is not only unprofessional, it is a health

hazard. Store an extra outfit and shoes in your locker as backup.

Attitude

Be upbeat and positive. Treat everyone with respect, including nurses, fellow residents,

medical students, ancillary personnel, and other specialists, as well as your patients and

your superiors. Surgery is a team sport; nobody wants a whiner or complainer on their

team. Show enthusiasm for your chosen specialty; enthusiasm to learn begets

enthusiasm on the part of your senior residents and attendings to teach. Be open to

“The reward for work well done is the opportunity to do more.”

-- Jonas Salk, MD

6

learning from every situation you encounter; even a “negative” experience can serve as

an example of what NOT to do. Confidence on the one hand is a good thing, and

should come to you naturally as you gain greater clinical experience; arrogance,

however, is a dangerous character trait at any level. When you are tired and stressed,

you will be faced with all kinds of situations that will test your personal integrity,

judgment, and stamina. Try to view each challenge as a learning opportunity and do

your very best to avoid becoming defensive and hostile.

When you find yourself rotating on a subspecialty that you do not care for, or working

with a particularly difficult attending, do not let this affect how hard you work or how

well you work with others. Grit your teeth, keep your head down and your nose to the

grindstone. You can learn something by observing the strengths and weaknesses of

each of your colleagues. The world of surgery is amazingly small and the attending you

operate with today may be old friends with the head of that fellowship program you

want in a few years. Don’t burn any bridges. Keeping your goals in mind can help you

maintain perspective and keep you on track.

Behavior

Probably the most highly-valued characteristics of interns and junior house staff are

honesty, hard work, the ability to accept feedback and, particularly in the era of

resident work hour restrictions, efficiency (See Chapter 2, “Getting the Work Done”).

The greatest sins are laziness and being untrustworthy.

Beyond cultivating efficiency, you should identify and consciously emulate

characteristics of the surgeons you most admire. Do not imitate negative or juvenile

behaviors. Behave so that your honesty, integrity, sense of responsibility, and reliability

are never called into question.

Surgical residency is a long road with a number of physical and emotional challenges.

There is no doubt that at times you will feel overwhelmed. Don’t let it drag you down.

Do the best that you can and don’t be afraid to ask for help if you need it.

Professionalism

The ACGME (Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education)

1

has identified the

specific knowledge, skills, behaviors and attitudes, and the appropriate educational

experiences required of residents to complete Graduate Medical Education (GME)

programs. These are known as the six competencies (surgeons consider technical skills

to be the

seventh

competency). One of these (see Chapter 4) is “Professionalism”.

While there is considerable debate within the educational community regarding exactly

“You never know when you’ll be in need

of those you’ve despised.”

-- Cormac McCarthy, All the Pretty Horses, Knopf 1992

7

how professionalism should be taught, assessed, and remediated, it goes without

saying that you do not want your professionalism ever to be questioned.

Professionalism captures the essence of the physician’s duty to the public. The

construct includes such virtues as honesty, altruism, service, commitment, suspension

of self-interest, commitment to excellence, communication, and accountability.

Cultural Sensitivity

In your training and in your professional life, you will inevitably encounter attendings,

co-workers, and patients with very different cultural, religious, and political beliefs from

your own. In the professional setting, you must be respectful of these individual

differences. Avoid jokes or comments that degrade any member of society, be it an

alcoholic patient or a person who doesn’t speak English. Be aware of imposing your

own biases on others and letting these biases determine how you treat others. Keep an

open mind, learn about the challenges others face, and set a good example to others of

the sensitive, caring surgeon.

For more information, the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) has a

number of useful resources.

2

Do Not Gossip!

Hospitals can be miniature soap operas. Remember the walls have ears! Think before

you speak or act. Never malign one colleague to another, and avoid bad-mouthing your

fellow residents under any circumstances. Be mindful of what you say of others; it will

reflect on you.

Profanity

Profane language is simply unprofessional. Don’t use it.

KNOWLEDGE AND PATIENT CARE

Medical Knowledge and Patient Care are two of the six ACGME competencies. Surgery

residents are required to demonstrate knowledge of established and evolving

biomedical, clinical, epidemiological and social behavioral sciences, as well as the

application of this knowledge to patient care.

3

This includes an ability to critically

evaluate and demonstrate knowledge of pertinent scientific information and a

knowledge of the fundamentals of basic science as applied to clinical surgery. In terms

of Patient Care, residents must be able to provide patient care that is compassionate,

appropriate, and effective for the treatment of health problems and the promotion of

health. In addition, residents must demonstrate level-appropriate manual dexterity; and

develop and execute patient care plans.

Our character is what we do when no one is looking.

--

H. Jackson Browne

8

The obvious professional activity that distinguishes surgeons from other physicians is

performing operations. While good operative technique is critical to competence, the

fundamental ability surgeons MUST possess is incisive clinical reasoning and decision-

making. This allows surgeons not only to make an accurate diagnosis, but also to

conduct the operative procedure and manage the patient’s clinical course. The care of

the surgical patient is accomplished by a series of clinical decisions – some large, most

small – often in the face of incomplete data. Developing the ability to make reasoned

and prompt judgments under stress with overt confidence is essential to independent

surgical practice.

One of the criteria universally used to evaluate surgical residents is “fund of medical

knowledge”. An assessment of medical knowledge is made based on performance on

standardized tests such as the ABSITE (American Board of Surgery In-Training

Examination)

4

and on direct observation of your clinical behavior and decision making.

You will be assessed, usually at the end of each rotation, on whether you know what

you ought to know at a given stage in your training. If you are simply carrying out a

series of assigned tasks with no understanding of why, you will never become a

competent surgeon. Some knowledge is gained simply from experience. Nurses, scrub

technicians, x-ray technicians, and other ancillary personnel can be excellent sources of

practical tips. You can learn a lot by both watching and speaking with your attendings

and senior residents. Morbidity and Mortality (“M&M”) conference is an invaluable forum

to learn from the mistakes of others and how to handle complications when they arise.

Grand Rounds and other academic conferences are useful for reviewing certain clinical

topics and for staying abreast of new developments in the specialty.

Reading

Reading is an essential component of residency training. You will never gain a thorough

understanding of the complexities of surgery without spending time reading. Both

textbooks and surgical journals must become part of your own personal library. Surgery

is not a static profession – it is constantly changing and improving. New technologies

and advances in basic sciences have transformed the specialty of surgery just in the

past few decades. One of the great joys of being a surgeon is that you never get bored.

There is always something new to learn, so get into the habit of reading daily. Most of

the major texts and journals are readily available online and an entire library can be

carried in your pocket on your smartphone or electronic tablet, so there is no excuse for

not reading!

Reference Materials

Most surgery training programs subscribe to the SCORE (Surgical Council on Resident

Education) curriculum,

5

the American College of Surgeons Fundamentals of Surgery

Program,

6

and/or UpToDate.

7

Every surgery resident should USE at least one standard

surgical text and a good atlas. (See the Appendix for suggestions.) Review every

surgical diagnosis and procedure preoperatively in your preferred text and atlas.

Prepare for every elective surgical case, particularly the first time you encounter a

9

problem or procedure. Adults remember best those things that they learn experientially.

Learning that is motivated by reading about your patients is likely to be remembered for

a lifetime. Besides having a general idea of the operative steps, you should also know

the indications for and possible risks and complications of a given operation or

procedure, and alternatives.

Study Habits

As a medical student, you could spend a week in the library and “cram” for an

examination. In residency this amount of protected time will not be an option, and this

approach is not recommended in any case. Therefore, you need to adapt your study

habits and find a way to study in shorter but more frequent time periods. Here are

some hints for reading during residency:

Carry a pocket copy of one of the major surgical texts (or an electronic

version) with you at all times. This will help you learn the basics and serve as

a reference for you to understand your patients’ problems, and can alert you

to related concerns.

Formulate a reading program that will ensure adequate coverage of the

relevant material for the service on which you rotate. Read all the pertinent

material. Set a specific goal for your reading every day,

and stick to it!

Don’t

underestimate the amount that can be learned in short periods of study.

Utilize the quiet times when you are on call to read.

Pick one journal and read it each month, even if you only skim it.

The

Archives of Surgery

and

American Journal of Surgery

are good choices. Read

through the abstracts or the summaries, and if there is time you can read the

articles in full. You will likely receive a few “throw away” journals in the mail

for free. Tear out the better articles and keep them in your coat pocket for

reading during down-time.

Review

Selected Readings in General Surgery

, and make sure you read

the overview each month (see Appendix).

Look upon your reading time as a treat, not as a chore.

Ask for suggestions on specific reading from your attending or senior

residents, particularly if you encounter something new that is not covered in

your texts.

If your program has enrolled residents with the American College of

Surgeons Resident and Associate (RAS) Program,

8

this will give you

access to many online resources such as

Access Surgery

.

9

MAKING DECISIONS

Seasoned judgment is the consequence of making decisions, observing the results, and

learning from both successes and failures. Much more is learned from mistakes,

particularly one’s own, than from things that go well. It is all too easy for the intern and

junior resident to focus on pragmatic immediate tasks to be accomplished for the

10

patient, chief resident, or attending, rather than considering the problem the patient

presents as an exercise in diagnosis and management. Only by actually making

judgments and observing the consequences of those judgments will you develop the

confidence to function independently. With each new patient, try to evaluate the

problem, make a differential, and formulate a plan of action in your own mind, even

though others may have presented the case signed, sealed, and delivered.

Be complete in your work-ups; you will often find things that others miss, such as

identifying a colon cancer by rectal exam on a hernia patient. Quality almost always

trumps speed. If your findings are not in agreement or you identify something not

previously documented, speak up and pass on the information in a respectful and

discrete manner. Many of your senior residents primarily will appear to value the

speediness with which you complete your work. But in the long run, you will learn more

if you force yourself to think past the admission H&P. If an operation is indicated,

decide which one, the ideal timing of the procedure, if any additional studies are

needed preoperatively, and the alternatives to surgery. Do not stop thinking! This

sounds kind of funny but it can be a real challenge when you are trying hard to

complete a long list of daily tasks. Review the radiographs of your patients with a

radiologist so you learn to read films yourself. Go to the pathology lab and view the

slides of specimens. Follow up on autopsy results when patients die; this is a very

useful and usually underutilized learning opportunity. Ask attendings for follow-up on

patients who have been discharged if you don’t have an opportunity to see a patient

yourself. This is increasingly important given the compromised continuity in patient care

that may result from work hour restrictions.

Plan of Action

When presenting a new case to the chief or attending, have a plan of action already in

mind and suggest it. Only by demonstrating your own problem-solving abilities will you

be judged capable of being a surgeon. At the very least, whenever a new diagnosis

comes up, review the appropriate section in your preferred pocket resource.

ROUNDS

The style of rounds will vary with your program and the hospital service on which you

are rotating. Chief resident morning rounds tend to be devoted primarily to patient

care, while attending rounds serve the dual purpose of teaching as well as keeping the

staff informed of patients’ progress. If you are in a private hospital, you may find you

only make rounds with individual surgeons to whom you have been assigned. This can

get challenging if several round at the same hour, but won’t round together; if this

happens, always inform your attending(s) of this conflict so they know where you are.

If you are not sure how to choose which attending to accompany on rounds, ask a

senior resident.

11

Your behavior and performance on rounds is of utmost importance during internship

since this will be your first and best chance to prove yourself. It will also be your most

frequent exposure to staff, and the decision of whether or not to assign cases to you

can depend on it. Be sure to read Chapter 2 on “Getting The Work Done.” Here are

some additional tips:

• Be on time.

• Pay attention. Idle chitchat and socializing is a great way to miss important details

of patient care that could have an adverse impact on patient safety and on your

evaluation by the attending.

• Know the patients and be able to give a BRIEF description of their

problems. This usually consists of the patient’s age, current surgical diagnosis

and procedure (planned or completed), date of the procedure, current status and

clinical plan going forward. However, the preferred format may vary within

specialties so observe how the senior residents present to the attending. Be ready to

review vital signs and their trends, pertinent labs and imaging studies, pertinent

physical exam findings, etc. Formulate a plan for dealing with any problems you

have identified and present them for approval.

• Make sure people can see and hear you. Move to the front if someone else has

been presenting before you. Use note cards as needed, but don’t “read” everything;

show you know the patient. Speak up and speak clearly. Make

declarative statements, bringing your voice down at the end of a sentence. Do not

end your remarks, ideas, and treatment plans with a tag question such as “don’t you

agree?” “Okay?” “You know?” These expose your uneasiness and need for

reassurance. Hedging phrases, for example “sort of, kind of, and could be” also

diminish your impact. Use strong verbs such as “I will...” and declarative statements

like “my plan is to...” rather than “you could...”, “maybe I would...” or “I would like

to...”

• Stay organized. Present patients in a logical, orderly fashion. Know what you are

going to say before you say it. Give the patient summary, vital signs, physical

examination, lab results, radiology results, assessment and plan in a consistent

manner. Jumping all over the place makes you look disorganized in your approach

to clinical problems and your ability to formulate a plan for further work up and

treatment. It also makes it difficult for those listening to understand what’s really

happening with a patient.

• Keep track of tasks. Use an organized patient list to take notes on rounds. Make a

checklist of tasks to do and test results to follow up on at a later time. Run this list

prior to leaving for the day to ensure that all of your patient care has been

completed and that the appropriate information has been checked out to the on-call

resident. S

ome procedures require specific preoperative order sets (such as a bowel

prep for colon surgery – see the chapter on “Getting the Work Done”). Your chief or

attending may forget to mention the orders to you, assuming you already know

them. If it is an emergency, look it up, but at the very least get some experienced

help if you are unclear about anything you are tasked to do.

12

• Don’t be afraid to say “I don’t know” or “I haven’t done that yet.” NEVER

make up lab values or x-ray reports if you don’t know them, even when you

should

know them. NEVER say you have done something if you have not. This is both

unethical and dangerous, and will get you fired. If you normally work hard, pay

attention, and show interest, your superiors understand that some details will get

lost in the shuffle and they will not hold it against you. Lying is not the solution and

may be grounds for dismissal.

• Keep an online resource text in your coat pocket (or app on your mobile

electronic device), such as the Mont Reid Surgical Handbook

10

(see Appendix for

other references), in case you need to look up some basic information as you are

walking to the bedside of a more complicated case. For example, you might want to

double-check the correct weaning parameters on a patient who is about ready for

extubation.

• Anticipate needs on working rounds to make them more efficient. For

example, keep dressing supplies handy if you know a wound is going to need to be

checked. Everyone appreciates a timesaver.

• Keep a neat and clean appearance. If the attendings don’t wear scrubs on

rounds, you probably shouldn’t. Do not carry food or drinks with you on rounds.

• Have a good attitude. If good-natured bantering occurs, respond assertively, not

defensively. Learn to laugh at yourself. Don’t whine or pout.

PRESENTATIONS

Throughout your residency you will be required to present at various conferences, such

as M&M and Grand Rounds. The manner in which you do this will play an important role

in how you are perceived by your colleagues. Presentations should be viewed as an

opportunity to learn and enhance your reputation, and they require definite effort on

your part beforehand. If you are not well prepared, you will lose ground fast. For all

presentations:

Discuss the presentation beforehand with a more senior resident. They

have experience giving presentations and are an invaluable tool for which format

to use, what topic to present, what information needs to be included, and

questions that might come up from the attendings. Learn from their experience.

Always inform the attending responsible for the patient if their case is to be

presented in M&M.

Make sure you are on time. If you are detained in the OR or have an

emergency, arrange for another resident to present the case.

“If all my powers and possessions were to be taken from me with one exception,

I would choose the power of speech, for by it I could recover all else.”

-- Nathaniel Webster

13

Be concise. Speak clearly and precisely. Present only the data that is

pertinent to the specific conference or rounds at which you are speaking. More of

the H&P details will be required at a case presentation conference than for a

Morbidity & Mortality conference, where the main issues are the surgery

performed and the complications.

Speak loudly enough to be heard by everyone present. If a microphone is

available, use it. Make a conscious effort to improve a soft voice, stammer, or

language difficulty. Practice speaking in a similar room, with a friend or two to

critique your efforts. Nothing makes a worse impression than if you can not be

heard or understood. Avoid talking too fast or using a high-pitched tone; these

are dead giveaways that you are nervous. Serious performance anxiety can

sometimes be treated medically; we advise seeking professional advice regarding

the medical treatment of anxiety if you feel your situation warrants it.

Check the dress code for presenters. Abide by it.

Plan what you are going to say carefully. Speak from note cards with key

words until you gain experience and confidence. Avoid memorizing a script, as

you are more likely to lose your place this way. Aim for brevity and clarity.

Continue on if you stumble. There is no need to profusely apologize, as this

tends only to draw attention to the error.

Think in advance of questions you may be asked. Either include the

answers to these questions in your presentation, or be prepared with the

answers at the end. If there is a visiting professor, ascertain his or her area of

expertise ahead of time and be prepared for more esoteric questions. Do not

guess an answer to a question or make an excuse for why you can not answer.

Simply reply that you do not know, but that you will make an effort to find out, if

that appears to be required. Be certain that you know the evidence-based

medicine to support your decisions.

After the conference, seek feedback on your performance by asking

senior residents and/or trusted friends. If you make mistakes, try not to

repeat them at the next presentation.

Preparing for higher profile meeting presentations (local, regional or

national).

11

• Practice, practice, practice. Plan on giving at least one “practice”

presentation, complete with slides, to your mentor well in advance of the

meeting. Check out the podium set up in the break before the talk so that you

know how to advance the slides and use the pointer. If necessary adjust the

microphone to your height. If water is provided, hide a glass under the podium

so that you can access it if needed.

• The first thirty seconds of your presentation are CRUCIAL. Unless you

are otherwise instructed, the usual format for a research presentation is:

Background, Purpose, Methods, Results, Conclusions and Study Limitations.

14

• If presenting from slides, standardize the background and color

formats of your slides. Studies show that light color backgrounds with dark

color letters are the easiest on the eyes. The Society or Organization to which

you are presenting may ask you to use a specific format or PowerPoint template.

Alternatively, your institution might mandate a specific institutional format, so

check with your mentor in advance. Stick with three or fewer colors for word

slides and use picture slides in place of text slides whenever possible. The font

should be at least 24pt and avoid more than about ten lines of text on the slide.

Avoid reading your slides. The bullet points on slides should give the key words –

you provide the explanation.

• If using a laser pointer or computer mouse pointer, balance your hand on the

podium or with your other hand to minimize the appearance of tremors. Be

judicious in your consumption of caffeine before your presentation. Use the

pointer economically; there is nothing more annoying or distracting than sitting

through a presentation where the speaker points to every word on a slide.

• Prepare for questions. Begin answering the question with eye contact to the

questioner, then move to the rest of the room.

• Project confidence! Remember, you will usually know more about your topic

than anyone else in the room.

CALL

Taking call is an essential part of surgical training, whether it’s overnight call or a “night

float” system. However the ACGME no longer permits interns to take call and these

work periods should be referred to as “duty periods” whether during the day or at

night.

3

While the days of a trainee sitting at a patient’s bedside for 36 hours straight

are definitely over, there is no doubt that the hospital is a different place at night and

on weekends. You will have to make critical decisions with fewer senior residents and

fewer ancillary staff to support you. At the start of each rotation, establish expectations

with the chief resident about when you should call him/her. When you are new, a good

plan is to set up a specific time to call and “run the list”. This avoids calling with each

minor issue but provides you with a safety net.

ACGME requires that each program provide guidelines for resident supervision and

these should be made available to you at orientation. If in doubt, call a senior person!

There is ALWAYS backup and communication is essential. Often you will have your first

opportunities to participate in more difficult cases at night, as there are fewer senior

residents available to assist in the operating room. Night time duty periods translate

into caring for more patients, including those who are not personally known to you.

When an issue arises with a patient,

go see the patient

, especially if you are unfamiliar

with his or her hospital course or the issue is new to that particular patient. Efficiency,

prioritization, and triaging care are essential skills when you are covering many

services. Use your time wisely and call for help if it becomes overwhelming or any time

patient care is at risk.

15

While the duty schedule should be as fair as possible, it may not always come out equal

for a variety of reasons. If you feel that there is a systematic pattern of unequal or

inequitable night or weekend duty, ask for clarification from the person responsible for

making the schedule. If the problem persists, your program director is the next best

person to approach. You and your fellow residents will need to perform as a team.

Adjustments in the schedule may be necessary to cover unexpected absences. You

never know when you will require emergency leave and they will pick up the slack for

you. In general, surgery is a team sport and being selfish is not appreciated.

Call provides an opportunity to gain some independence in decision-making and triage.

Maintain a good attitude about why you’re there and take advantage of any

opportunities you have to learn new skills and management strategies. In the morning,

shower and try to look as fresh and alert as possible, no matter how little sleep you got

the night before. Most people will know you were up all night, but that is no excuse for

a disheveled appearance. You can do it!

Duty Hour Restrictions

Residency Programs must ensure their trainees strictly adhere to an 80-hour work week

to maintain accreditation. You are required to document your hours and you must

speak up if you are scheduled to work more than the ACGME regulations permit or if

you are encouraged to enter your duty hours dishonestly. Training programs are

penalized for duty hour infringements, so the program director should be appreciative

when a problem is brought to his/her attention. Use your best judgment regarding the

use of your time, and let your chief resident know in advance if you think that you will

not be able to comply with the hours. Your program should be setting up rotations to

facilitate compliance, and you should be encouraged to speak up when you are not able

to comply. Adjustments may be necessary on occasion to successfully do this, and you

should discuss this with your chief resident if the schedule for the week or events have

arisen that would put you over the 80-hour limit. This may mean sacrificing cases;

hopefully good planning and foresight will help prevent this.

Patient Hand-Offs

Patient hand-offs are an integral element of patient care, and regularly passing off

information about your patients and associated “to-dos” is the rule. It will benefit you to

gain a reputation as a resident who takes care of the necessary tasks during the day.

Knowing your patients well and communicating this will be critical to the best care of

your patients, and will contribute to your reputation as reliable, thoughtful, and

considerate of others. Organization and communication are extremely important skills to

ensure optimal quality patient care.

12-14

REFERENCES

1. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)

http://www.acgme.org/acWebsite/home/home.asp. Accessed 6/6/12

16

2. American Association of Colleges of Medicine (AAMC).

https://www.aamc.org/download/54340/data/tacctbibalpha.pdf. Accessed 6.6.12

3. Surgery Residency Review Committee Program Requirements

http://www.acgme.org/acWebsite/downloads/RRC_progReq/440_general_surgery_01

012008_07012012.pdf. Accessed 6.6.12

4. American Board of Surgery http://www.absurgery.org/. Accessed 6.6.12

5. Surgical Council On Resident Education (SCORE) Curriculum.

https://portal.surgicalcore.org/. Accessed 6.6.12

6. American College of Surgeons Fundamentals of Surgery Curriculum.

http://www.facs.org/education/fsc/index.html. Accessed 6.6.12

7.

UpToDate

. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed 6.6.12

8. American College of Surgeons Resident and Associate Society.

http://www.facs.org/ras-acs/index.html. Accessed 6.6.12

9. Access Surgery. http://www.accesssurgery.com/. Accessed 6.6.12

10. The Mont Reid Surgical Handbook, 6

th

Edition. (Scott Berry et al., 2008, Mosby

Yearbook, Inc.)

11. Taylor K et al. “Effective Presentations; How can we Learn from the Experts?”

Medical Teacher

1999; (21):5-11

12. Greenberg CC, et al. “Patterns of Communication Breakdowns Resulting in Injury

to Surgical Patients.”

JACS

2007; 204: 533-540.

13. Singh H, et al. “Medical Errors Involving Housestaff: A Study of Closed

Malpractice Claims from 5 Insurers.”

Arch Intern Med

2007; 167: 2030-2036

14. Arora V, Johnson J. “A Model for Building a Standardized Hand-Off Protocol.”

Jt

Comm J Qual Patient Saf.

2006; 32(11):646-655.

17

Chapter 2: GETTING THE WORK DONE

The balance between service and education is a fine one because residency training

was founded on an apprenticeship model where both are important.

1

In addition,

residents are hospital employees who are paid to provide services that include ordering

tests and completing paper work. Occasionally this work will appear to be demeaning,

but it is essential to appreciate and value service to the patient as part of your

education to become a health care professional.

2

INTERNSHIP

The keys to surviving internship are organization, efficiency, and prioritization of tasks.

Time is a precious commodity and must be managed expertly or you will be lost – a

dangerous situation both for an intern and patients. The primary and essential role of

an intern is to be the gatherer of data, keeper and communicator of information, and

doer of tasks. The intern’s role is to learn about surgical disease processes and to

acquire the basic surgical skills necessary for a career in surgery. (However, more

senior residents rarely perceive operating as a priority for the intern.) Internship is an

exciting time filled with new educational experiences, including adjusting to a new role.

It is vital to recognize that as an intern you are the team’s foundation. The intern truly

is the eyes, ears, and hands of the surgical team outside of the operating room. If you

recognize the importance of this role, you will be able to find reason and purpose in the

sometimes mundane and sometimes overwhelming number of tasks to complete.

Remember the entire team and its patients rely on a good intern getting the work done.

Pay Attention. Truly listen to what is being said on rounds about the patients and

their proposed plans of care, both short- and long-term, and write it down. Important

information is communicated, and understanding it and relaying it accurately are

essential for optimal patient care. Not only does paying attention to patient plans help

make you efficient and organized in completing tasks, but it can also be seen as a

learning opportunity on pre- and post-operative patient care. It is beneficial to learn

and remember the patient care preferences of individual attendings with whom you

work. (Also see “Rounds” in Chapter One.)

Write it All Down in One Place. As soon as a plan is formulated, put it in writing.

You will NOT remember everything that is supposed to happen every day to every

patient. Many programs have interns use clipboards, patient lists, etc. Whatever system

you use, be consistent and always write it down in one place.

“I long to accomplish a great and noble task, but it is my chief duty to accomplish

humble tasks as though they were great and noble. The world is moved along, not

only by the mighty shoves of its heroes, but also by the aggregate of the tiny

pushes of each honest worker.” -- Helen Keller

18

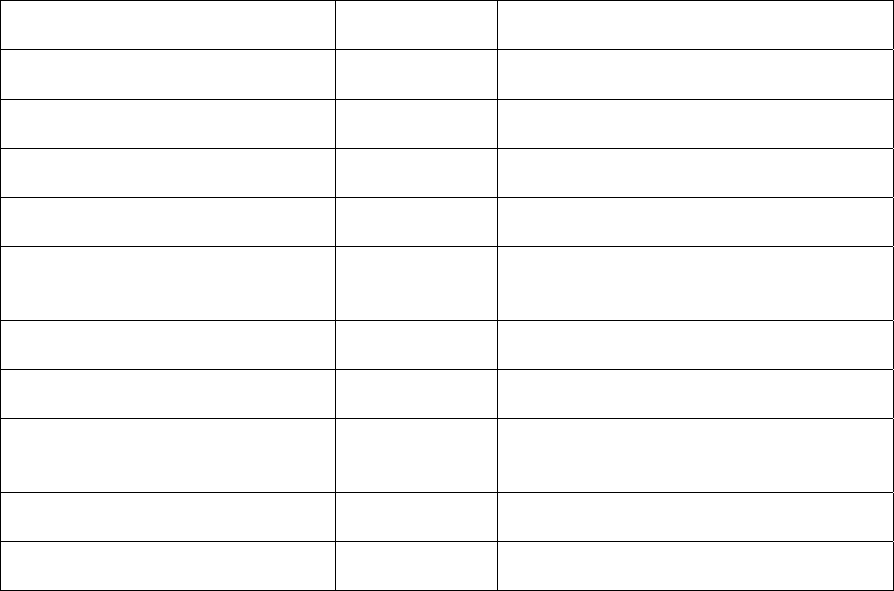

At a minimum, you should always have the following information at hand:

• Patients – name, age, diagnosis, location, attending, ID number, significant

medical history, post-operative day, diet status (NPO/clears/regular), drains/lines,

and pertinent medications, including antibiotics, etc.

• Labs – which tests on which patients, and when results should be ready.

• Radiology – which tests, which patients, when results should be available, who

needs to be scheduled, when the test will be performed, and what prep, if any, is

required.

• Consults – what consulting service, which patients, which resident or attending

to call, and most importantly, the reason for a consult. Descriptions of key clinical

issues, the reason for and urgency of the consult are all important in

communicating with consultants. Ascertain if any specific tests should be ordered

for a patient so that the results are available for the consultant. For example, if a

patient needs a cardiology consult, often an ECG and Echo should be ordered/

completed. Also, be sure to ask when the consultant will be able to see a patient,

and the name and pager number of the individual to contact for follow up. Always

treat consultants with respect and never criticize their recommendations in front

of the patient. Also, avoid preempting a consultant decision; for example when

consulting a cardiologist do not tell the patient that the cardiologist will want to

do a cardiac cath as this will create mistrust if the consultant offers an alternate

management plan.

• If you have trouble scheduling tests and procedures or obtaining a

consult, let your senior resident or attending know as early as possible. Leave

the decision up to them regarding whether to wait or press the issue. They may

also have better persuasive ability than you do by virtue of their seniority.

• Other studies – ECGs, Echos, etc.

• Bedside Procedures: dressing changes, IV starts, CVP lines, NG tubes, drain

tubes to be pulled, etc.

• OR schedule – who needs pre-op and post-op checks (and on what cases you

have an opportunity to be in the operating room).

• Admissions – scheduled and emergent. Don’t forget to add these patients to the

service list and check their labs, etc.

• Paperwork – dictate discharge and transfer summaries, contact primary care

physicians, prepare prescriptions, and any special needs for discharge such as

physical therapy, ostomy teaching, home TPN, etc.

• Attending, resident, and ancillary staff contact information, commonly

used phone numbers, door codes, etc. Make sure you know your attendings’

preferred mode of communication; some may not wear pagers and prefer to be

contacted by other means.

An important note: Cross coverage and sign outs (or hand offs) are increasingly

important (see “Patient hand-offs” in Chapter 1). Make sure that your notes are

complete, clear and legible so that anyone taking care of your patient can pick up

19

where you left off without skipping a beat. Be complete in your sign out. Note the

recurring themes of how important organization and communication skills are. This

applies to both verbal and written forms of communication.

Do It Now. Following morning rounds, begin the day’s work

immediately

. Organize the

day by looking at the list of things noted on rounds and consolidating as many as

possible, as well as prioritizing which tasks need to be completed first. For example, sit

down and make all phone calls at once; if lab results are available by 10 AM, check

them at 10:15. Waiting until the afternoon to check morning lab results may create an

avoidable situation of discovering that the wrong lab was sent (or was never actually

sent), or finding critical lab values that are not addressed for several hours after being

available. Do not procrastinate, even on a light day! Your goal should be to have all the

“routine” work completed before noon. Tasks such as consultations and imaging

studies, which depend on others, should be scheduled first. The early bird does catch

the worm; tests scheduled first thing after rounds will usually be run earlier than if you

wait until the afternoon. Begin the discharges as soon as the above orders have been

entered. Getting people on their way allows rooms to be turned over, nurses to be

freed up, and admissions to come in. You never know what disaster lurks in the ED or

when a surprise admission from clinic may wreck plans to do things later. If a patient is

planned for discharge the next morning, complete the discharge paperwork the day

before if possible. Delegate where you can, but be sure to follow-up on your assistants

(e.g. medical students or physician assistants).

Always Make Waiting Times Productive Times. While waiting for the next case to

begin, write post-operative orders, make phone calls, read your pocket textbook or

study from an online resource. It may be tempting to sit in the lounge and socialize, but

most lounge conversations are rarely educational unless you make a point to turn the

conversation to the case at hand. (On the other hand, occasional social conversations

may keep you from appearing stand-offish.) While scrubbing, ask the attending or

senior resident about post-operative management, any preferences regarding orders,

dressings, drains, tubes, etc. Also use the time to develop and discuss your learning

objectives for the case.

3

Start Admission H&Ps, even if you don’t think you have time to complete them. You

may think you need more time than turns out to be necessary and you are apt to never

feel you have a large enough block of time. Just Do It! This can be especially

important if you need a translator or some family member who may not be there when

you come back, prolonging the time required. You may also discover tests that have not

yet been ordered that will need to be expedited after you get the patient’s history and

medication list.

“The surest way to be late is to have plenty of time.” -- Leo Kennedy

20

Make Learning a Priority. Work must be completed, and sick patients tended to, but

always remember that you are there to learn the art and science of surgery. You must

be proactive about your surgical learning experience. Make every effort to spend as

much time in the OR as possible. Your presence there can only be interpreted as

enthusiasm for surgery, and your absence a lack thereof. Attending surgeons are

important to your evaluations and your future. They will be more likely to give you

better cases and to assume a more active mentoring role if you take the initiative to be

in the OR.

Know Your Cases. Be sure to obtain the case assignments at least the day before.

Always make time to read about the operation beforehand. Meet the patient before the

surgery, and be sure you know the indication for the operation, pertinent anatomy, and

main surgical steps. Never go to a scheduled case unprepared; this will leave a poor

impression on the attending and senior residents, and most importantly, will cheat you

from a full learning experience. (For surgical resources, see Appendix.) Also, team

members unfamiliar with the patient history can pose a risk to the patient.

Keep a Case Log and Copies of Your Operative Reports. You will need a

complete list of ALL your defined category cases, especially ones in which you are the

primary surgeon or the first assistant, in order to sit the American Board of Surgery

Examinations.

4

Most residency programs require residents to submit a list of cases at

regular intervals. You must also keep track of procedures, including chest tubes

inserted, central lines and Swan-Ganz catheters placed, endoscopies, etc., as well as

non-operative trauma and ICU cases that you have managed. (For your own

information and edification, also record any complications you may have had.) For each

of these procedures record the patient’s name, medical record number, date, attending

surgeon, service (general surgery, plastics, etc.), the procedure, and what role in the

procedure you played (primary surgeon, first-assistant, teaching resident, etc.). Some

residencies will also require you to list the CPT code assigned to that procedure. Some

residents do this by imprinting an index card with the patient and case information;

others use stickers in a logbook, or personal organizers. (If you use a computer system,

be sure to have an updated backup at all times! Many residents have lost their case

logs this way.) Cases are logged in to the ACGME Website

5

electronically. Make sure to

enter your cases in a timely fashion and be disciplined about it. It is very easy to lose

track of cases. The American College of Surgeons also has a Website for logging cases.

6

Delegate. Let other people do their jobs. Learning to delegate is an important

component of being organized and establishing a leadership style. There is a tendency

for interns to believe that they alone need to solve all patient problems, such as

arranging transportation and/or dealing with social situations. Remember that social

workers, ostomy nurses, and other ancillary personnel are trained to take care of

certain aspects of patient care and you should let them do it.

21

Inform Your Superiors. Make a point of informing your chief resident and attending

of tasks accomplished and any significant changes or abnormal results identified

throughout the day. If something you think is very important comes up, inform your

chief between cases, or go in to the operating room. Be careful that you are not

interrupting at a critical point in a case. (Try asking the circulating nurse if it is a good

time or not, or just wait quietly off to the side within the peripheral vision of the

attending, who may speak to you when ready. Better yet, ask how your chief prefers

these types of things handled

before

such a situation arises.) Many times your

appearance in the OR will give you a chance to see something interesting, and it

informs your attending that you are both interested in the case and are staying on top

of things on the ward. Remember the importance of good communication. This is

essential when a patient’s condition deteriorates or there is critical information to share.

Teach the Medical Students. During your internship you will be acquiring the skills

you will need to teach students, which may continue throughout your career. You are

not expected to lecture, but you are expected to explain things and to be a role model

for them. Students are typically happiest when they are doing something they feel is

useful for patient care or contributing to the team, so assign them tasks within the

constraints of your institutional policies (e.g. in some institutions medical students are

forbidden to write in the medical record). Instill a sense of responsibility in the students,

but don’t jeopardize your reputation or your patients’ care by relying entirely on medical

students. When assigning tasks, establish a subsequent time to review what has been

accomplished. Recognize that

any

tasks you delegate to a medical student are

ultimately

your

responsibility. When students ask questions (academic or practical) to

which you do not know the answer, tell them where to find out. Don’t forget to specify

when you expect them to share the answers with the team. Keep in mind that medical

students are present to learn and to be part of the surgical team. For many, it is their

only exposure to a surgical service during their entire careers. Do not underestimate the

potential you have to positively influence their experience. Many programs recognize

outstanding resident teachers each year, or conduct “Resident as Teacher” Courses for

the residents. If a course is not available in your program, ask to participate in the

American College of Surgeons Resident as Teachers and Leaders Program.

7

Document Your Actions. In this litigious society, it didn’t happen if it’s not in the

chart. Every time you have a significant interaction with a patient, especially with a

critically ill patient, briefly note it in the chart. Not only is this good for medico-legal

reasons, it lets your attending and others know you are following the case closely. It

takes two minutes to write: you were called to the patient’s bedside for (x problem),

the patient was seen and examined, the pertinent findings, the assessment and plan

(labs, tests, or observation only), and the senior-level resident with whom you

discussed the problem and plan. Never use the patient record to argue with a

colleague. If you disagree with an entry, go and have a conversation.

22

Keep the Nurses Informed and Involved. The nursing staff is often stretched thin

in these days of managed care. By spending five minutes after rounds to inform the

nurses about the day’s plan for patients and answer questions, you will reap the

rewards of better teamwork, and from a practical standpoint may avoid unnecessary

pages. It’s important to communicate not just what needs to be done with a patient for

the day, but why, as it instills a sense of cooperation and allows the nurses to prioritize

their aspects of patient care. You will find that most nurses will work in the patient’s

best interest as well as yours when they understand why a certain task needs to be

completed sooner rather than later. A collaborative approach usually is the best

approach.

Patients First. There will be times when you are needed in multiple places at the

same time and you just can’t do it all. A general rule for staying out of trouble is to

“keep the interest of the patient foremost in your mind.” If a patient is critical and you

are expected at a conference, for example, ask a nurse or someone else to call the

appropriate superior (senior resident or attending) and let him or her know where you

are and why you can’t be there. If conference attendance is truly required, make sure

your attending knows of any significant changes in your patient’s condition, particularly

if the patient is deteriorating. Few attendings will get upset when you miss conference

if they see you were putting the interest of a sick patient first. (This does NOT apply to

non-critical issues and things that should have been done previously, like discharge

summaries.)

Maintain a Positive Attitude. Residency and hospitals can be extremely frustrating

and aggravating. Internship is filled with many challenges, including learning how to

work with ancillary staff during stressful and overwhelming situations. By learning the

names of support staff, returning pages in a cordial manner, and treating nurses as

colleagues (even if at times they may be hostile or even question your abilities as a

physician), you will be amazed at how much you will benefit. There will be times when

your ability to maintain a positive attitude will be challenged. These are the moments to

really shine by remaining steadfastly professional and composed. If needed, take a

minute alone during times of chaos to refocus and refresh, whether it’s in a restroom or

call room.

Take care of yourself. Integrate taking care of yourself into your daily work schedule.

It is important to make sure you eat more than one meal a day; eating healthy gives

you energy to get your work done and you will be less tired. See Chapter 6, “Taking

Care of Yourself” for additional advice.

Integrate study time into your daily routine. Even when you come home dead tired,

make it a point to read an article from PubMed about a topic you encountered in a

consult, or keep flashcards at your bedside.

23

Again, the keys to surviving surgical residency are organization, efficiency, and

prioritization of tasks. Follow the suggestions above, and remember that you can and

will make it through surgical training!

JUNIOR RESIDENT

As you move up the hierarchy of the surgical team you are expected to assume

increasing levels of responsibility for patient care. It is very important that you know all

the critical history of patients on the entire service whether you were the resident

surgeon on that case or not. This is imperative to providing good care, and models

behavior for the intern.

You will be expected to take a more active role in the decision-making process,

particularly in the diagnostic work-up and treatment planning for patients coming

through the emergency room. It is also a reasonable expectation that you will facilitate

this process for the interns. The expectation that you will take more responsibility as

you become more senior extends to the operating room, and you are expected to start

taking initiative (i.e. asking for instruments). In surgery you are expected to take

charge and be more assertive than in other specialties. If you aren’t, you just get

ignored. As Junior Resident you are also expected to be able to “fill in” for the Chief

Resident whenever he or she is detained in the OR or otherwise unavailable to make

decisions and report to the respective attendings.

CHIEF RESIDENT

As Chief Resident you are the official surgical team leader. You are expected to

organize the team in an effective and efficient manner to ensure that patient care is

optimal. This requires a great deal of organization and coordination. It is important to

orient all team members, including medical students and interns, to the team as early

as possible in the rotation. Inform them of the team schedule and explicitly state your

expectations and preferences. Make sure everyone knows the importance of his or her

role on the team. It is important to remember that junior residents and students will be

looking to you as an advisor and mentor. Recognize that your behavior is constantly

being observed and sets the tone for the team.

Patient issues must be identified and addressed on morning rounds, and responsibilities

are clarified and delegated at this time. It is important to be sure at the end of patient

rounds that all team members fully understand what is expected of them that day. An

open forum for communication is essential to good team dynamics. This is the best way

to ensure that the team is functioning as a system of checks and balances instead of

inefficient redundancy. Team members will not work to their full capacity if they do not

have the sense that they are making significant contributions and getting back a sense

of accomplishment. Giving feedback is another essential role of the team leader.

24

Remember that effective feedback should be FAST: Frequent, Accurate, Specific and

Timely. In addition, it should be delivered in a private environment.

RESIDENCY CALENDAR

Here is a list of things you can be doing to simplify your future as residency progresses.

Internship:

• Begin keeping a case log.

• Begin keeping an OR diary.

• Keep copies of your op reports. Don’t forget to record and dictate procedures such

as CVP lines, chest tubes, etc.

• Pick a mentor, or at least identify some potential ones.

• Scrub and do all the cases you can while still getting your ward work done. Even

being a second assistant can be a valuable experience.

• Begin looking for a topic of interest for research time. If you plan to go into research

after your second year, apply now for grant funding.

• Apply for membership in the American College of Surgeons, Resident and Associate

Society.

Second Year:

• Request fellowship information from several programs if there is a remote possibility

of you seeking subspecialty training.

• Arrange a lab year if you plan to do one (or two). Apply for grants.

• Continue your case log.

• Continue your OR diary.

• Scrub and do all the cases you can.

• Start developing your skills as a teacher to lower-level residents

Third Year:

• Begin the fellowship application process in earnest. Identify which programs will be

best for you, find people to write letters of reference, and make sure you have met

all the prerequisites.

• Finalize arrangements for a lab year.

• Continue your case log and OR diary.

• Scrub and do all the cases you can.

Fourth Year:

• Decide more definitely about your career path. Send for information on places

where you might be interested in practicing.

• Apply for fellowships.

• Continue your case log and OR diary.

• Scrub and do all the cases you can.

25

Fifth Year:

• Meet with the residency coordinator to discuss the requirements (including

paperwork) necessary for you to apply for your Boards and license. NOTE THE

IMPORTANT DEADLINES.

• Start looking for a job if you are not going to do a fellowship. Consider signing on

with a search firm or doing Locum Tenens if you don’t find the job you want.

• Get a permanent medical license in at least one state. The license you practice

under as a resident is usually conditional or temporary. You will need a permanent

license to take your Boards after completing residency. The application process

often takes 3-6 months.

• Fill out the preliminary application for the ABS Exam.

• Scrub and do all the cases you can. Before long, you will be on your own – possibly

alone. Offer to take a Junior Resident through a case while the attending supervises

without scrubbing. Ask the attending to give you more autonomy within the

constraints of patient safety.

REFERENCES

1. Reines, HD; et al. “Defining service and education: the first step to developing

the correct balance.”

Surgery

2007; 142 (2): 303-310.

2. Sanfey et al. “Service or Education: In the Eye of the Beholder?”

Arch Surg.

2011;146(12):1389-1395

3. Roberts, NK et al. “The Briefing, Intraoperative Teaching, Debriefing Model for

Teaching in the Operating Room.”

J Am Coll Surg.

2009 Feb;208(2):299-303.

4. American Board of Surgery http://www.absurgery.org/. Accessed 6.6.12

5. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)

http://www.acgme.org/acWebsite/home/home.asp. Accessed 6.6.12

6. American College of Surgeons Case Entry System.

http://www.facs.org/members/caselogquickstart.pdf. Accessed 6.6.12

7. American College of Surgeons Residents as Teachers and Leaders Course.

http://www.facs.org/education/residentsasteachersandleaders.html. Accessed

6.6.12

26

Chapter 3: IN THE OPERATING ROOM

Obviously, what distinguishes the specialty of Surgery is what we as surgeons do in the

Operating Room.

TECHNICAL SKILLS

Economy of Motion

A universal characteristic of the best technical surgeons is not speed per se, but

economy of motion

. You will be better off at first with slow, deliberate movements than

if you rush. Fidgeting around and multiple trial movements waste time and make for

poor technique. Proficiency and speed will come with repetition. Listen attentively and

try to implement technical suggestions that are offered during your cases. If you do not

understand a technical instruction, ask for clarification or for the attending to

demonstrate for you.

Skills Lab/Simulation

The current training paradigm whereby residents learn in the operating room under

direct supervision through graded responsibility was introduced by William Halsted a

little over a century ago.

2

While teaching residents in the operating room is effective, it

is inefficient, costly, and may increase patient morbidity. In addition, the psychomotor

and perceptual skills required for the newer techniques of laparoscopic and robotic

surgery differ from traditional approaches. Therefore, surgical education has placed

increased reliance on simulation technology in order to improve and evaluate learner

proficiency, and provide controlled and safe practice opportunities.

3

All surgery training programs are now required to have a surgical skills lab and a skills

curriculum.

4

Ideally, the skills lab should be located close to the OR, with 24-hour

access to allow practice during down time between cases. The American College of

Surgeons and the Association of Program Directors in Surgery have established a three-

phase national skills curriculum for all surgery residents.

5

Phase 1 involves a number of

basic surgical skills modules each of which includes objectives for performance,

guidelines for practice and instructions for testing.

Proficiency-based training refers to

the concept of learners practicing certain surgical skills until testing shows them to be

at a predetermined level of ability. Trainees be allowed to progress to more demanding

technical skills only after achieving this predetermined level. Residents must

demonstrate proficiency in the Fundamentals of Laparoscopic Surgery prior to taking

the American Board of Surgery Examination.

6

This is the first example of proficiency-

based criteria for trainee assessment in a high stakes examination, and others will

follow.

Simulation is defined as ‘‘a person, device, or set of conditions which attempts to

present education and evaluation problems authentically.”

7

The trainee is required to

respond to the problems as he or she would under natural circumstances. Frequently

27

the trainee receives performance feedback either because this is built into a simulator,

or given by an instructor during a teaching session. Medical simulation comprises a wide

spectrum of tools and methods that vary in cost from cheap knot-tying boards to the

much more expensive virtual reality robotic models to team training simulations. For

basic laparoscopic skills, the training experiences increasingly rely on tools such as

laparoscopic video trainers and high-fidelity virtual reality laparoscopic simulators.

Simulation training has been demonstrated to have construct validity in a growing

number of studies.

3

More importantly, skills gained by simulation training have been

demonstrated to lead to improved performance in the OR.

3

Many programs have

specific laparoscopic trainers with which you can practice on your own time in addition

to dedicated laparoscopic skills labs. Knot-tying boards are available from the major

suture company representatives such as Ethicon or Davis & Geck. The OR Supervisor

should be able to give you contact information. If possible, get a board even before

you

start your internship so that you can practice during senior year in medical school.

Consider buying a used or cheap needle holder and forceps to practice instrument

handling. (Disposable instruments used by some ERs are satisfactory).

Practice

There is no substitute for practice, or as Arthur Rubinstein answered a stranger in New

York when asked how to get to Carnegie Hall, “Practice! Practice! Practice!” The same is

true for surgery. Just as pilots are not permitted to fly until there has been a clear

demonstration that predetermined criteria have been met or proficiency has been

achieved, surgery residents should achieve proficiency in the skills lab prior to entering

the operating room.

1

Nothing will dissuade an attending from passing down a case more than your bungling

basic tasks such as tying knots. Learn to tie two-handed knots proficiently before doing

them one-handed. It may not look as “slick”, but some attendings are critical of junior

house staff using one-handed techniques. When practicing suturing, be sure to follow

the curve of the needle. Grasp the tissues gently with your forceps. Learn to reset the

needle in your needle driver without grabbing it in your fingers. Become proficient in

releasing instruments with both hands. Deliberative practice does make perfect. Start

slowly and deliberately. Speed comes with frequent repetition of precise movements;

they become more and more automatic until you do not have to think about each one.

Be a good retractor-holder, and you will earn appreciation. Understand the importance

of your role and don’t take it as an insult. You can learn a lot from watching more

senior people operate, even observing a case you may not do yourself for another

several years. When you are retracting for a case, or operating the camera in a

laparoscopic case, observe

actively

. Watch the overall conduct of the case, listen and

try to learn the names of the various instruments and which instrument is used in which

circumstance. Observe how the instruments are held, and how the tissues, needles, and

sutures are manipulated. Ask a scrub tech to go over the names of instruments with

you quickly prior to or after the case if the instruments are not familiar to you. When

28

retracting, try to stand as still as possible. Try to anticipate how you can best help. If

you are not sure what to do, just keep doing exactly what you are doing, and don’t

move. Listen carefully when instructed. Don’t be afraid to ask questions at an

appropriate time. Let it be known that you are there to learn; not just putting in your

time, and not trying to catch up on your sleep. If you can not see the operative field,

don’t risk losing the surgeon’s view just to satisfy your own curiosity. Ask to see the

anatomy at an appropriate time, such as when things are going well, when waiting for

x-rays, or right after a stitch has been tied and cut and the surgeon is getting ready to

put in another. Try to correlate the anatomy you are seeing with the pictures in the

atlas you used. If it doesn’t make sense, ask the surgeon to explain it to you. Keep

asking until you get it straight. After each case, review the atlas once again to reinforce

what you have seen and done.

Observe

Find out who in your program is known to be the best

technical

surgeon; this may or

may not be the same person as the fastest or the best surgeon overall. Try to scrub on

that surgeon’s cases, or at least make it a point to observe his or her technique. You

will soon know which surgeons you want to imitate. The more you can learn about their

techniques, the better you will be able to visualize and practice those moves yourself.

Keep an OR Diary

In addition to the Case Log, develop an “OR Diary”, which serves a different purpose

than an operative log. After every operative case, take five minutes and jot down what

you learned during that case; write down “pearls” and the kinds of technical tips that

aren’t found in atlases. Making sketches to reinforce the surgical anatomy may be

helpful. Record the idiosyncrasies of the particular attending (e.g. suture preferences);

you can review this information in advance of the next case you do with him or her.

Make a note of what you think you did well operatively, and what you would specifically

like to improve the next time you do a similar case.

OPERATING ROOM STRATEGIES

It is important for all residents to scrub on as many cases as possible, and a

certain number of defined category cases.

4

Competing patient care obligations can pose

significant obstacles, but this must be a priority. Here are some strategies to help you

“get” cases:

• Read thoroughly on all assigned cases the night before. Even if you will only

assist on a case, try to read as much about it as possible. Review each patient’s

medical record, including the pre-operative workup and the indication for the

operation. There is something to be learned from every case you participate in; even

if you are doing 5 hernias in a day, use every case as an opportunity to learn

something new.

29

• Discuss the case with the attending at the scrub sink or in the lounge so that

she or he knows you have read about it and are prepared to do the case. Volunteer

a learning objective for the case; for example “today I would like to focus on

improving my dissection of the hernia sac.”

• Arrive early. Evaluate the patient in pre-operative holding and ensure that

everything is in order to go to surgery. Be in the OR ready to go even before the

patient is asleep. Show that you know how the patient should be positioned for the

case. Be gloved and gowned first so that you can immediately step to the position of

the operating surgeon (usually the right side of the patient) if invited.

• Don’t be shy. Ask if you may start the case, or if you can at least make the

incision. Find out the attending surgeon’s preference on incisions; some like to go

straight down to fascia with the first cut, while others prefer just cutting the dermal

layers with the knife, then cutting down to fascia with the electrocautery. Sometimes

just by starting the case, you will be allowed to continue on through the rest.

• Learn to anticipate. The major steps taken during any operative procedure should

be familiar to you, at least in general terms. Have an outline in your mind and try to

anticipate what the next step in the operation will be. This will make you a better