University of Montana

ScholarWorks at University of Montana

Institute for Tourism and Recreation Research

Publications

Institute for Tourism and Recreation Research

11-2018

! $ #%$'( %#$"&! !

! $"%$! %#$"& $ &##

"&

University of Montana - Missoula

"$""

University of Montana - Missoula

!""#!

University of Montana - Missoula

Let us know how access to this document bene>ts you.

Follow this and additional works at: h?ps://scholarworks.umt.edu/itrr_pubs

Part of the Economics Commons, and the Leisure Studies Commons

=is Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Institute for Tourism and Recreation Research at ScholarWorks at University of Montana.

It has been accepted for inclusion in Institute for Tourism and Recreation Research Publications by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at

University of Montana. For more information, please contact scholarworks@mso.umt.edu.

Recommended Citation

Sage, Jeremy L.; Bermingham, Carter; and Nickerson, Norma P., "Montana's Out>?ing Industry - 2017 Economic Contribution and

Industry-Client Analysis" (2018). Institute for Tourism and Recreation Research Publications. 376.

h?ps://scholarworks.umt.edu/itrr_pubs/376

Montana’s Outfitting Industry

2018

Montana’s Outfitting

Industry

2017 Economic Contribution and Industry-Client

Analysis

Jeremy Sage, Carter Bermingham, Norma Nickerson

11/25/2018

This study evaluates the state of Montana’s outfitting and guiding industry in 2017. Characterizations of

both the guides themselves and their clients are provided.

ii

Montana’s Outfitting Industry: 2017 Economic

Contribution and Industry-Client Analysis

Prepared by

Jeremy Sage

Carter Bermingham

Norma Nickerson

Institute for Tourism & Recreation Research

College of Forestry and Conservation

The University of Montana

Missoula, MT 59812

www.itrr.umt.edu

Research Report 2018-16

November, 2018

This study was funded by the Lodging Facility Use Tax.

Copyright© 2018 Institute for Tourism and Recreation Research. All rights reserved.

Montana’s Outfitting Industry

2018

iii

Abstract

In recent years, nonresident visitor spending on outfitters and guides has surpassed that of spending on

retail goods, making it the fourth highest spending category behind only fuel, lodging, and dining out.

This rise comes despite only five to six percent of the visiting population taking part in these activities.

This observation reiterates findings from the 2007 Montana Outfitter and Guide study characterizing the

outfitting industry as high value, low impact.

In 2017, the $3.4 billion in spending by nonresidents in Montana produced a total economic impact of

$4.7 billion in economic output. Though a small percent of visiting groups take part in some type of

guided or outfitted experience, those who do stay longer and spend more per day. In 2017, the 5.4

percent of all visitors that had a guided or outfitted experience spent a total of $791 million dollars while

in Montana, accounting for nearly a quarter of all visitor spending. Spending by visitor groups taking part

in outfitted or guided experience generates more than 16,000 jobs and nearly $1.3 billion in economic

output.

The 1,450 identifiable entities providing guided and outfitted services generate an average of $158,900

in revenue while serving 728,900 clients, 63 percent of whom are from out of state. These activities take

place across a wide spectrum of landscapes and waterways. Sixty-one percent of land based activities

utilized public lands. USFS and BLM lands led the way with 32 and 20 percent respectively of outfitted

trips. When it comes to Montana’s waterways, 79 percent of responding outfitters indicated their

activities relied in some fashion on waterways.

Highlights

Over 700,000 individuals took a guided or outfitted trip in 2017 in Montana.

Visiting groups who took a guided trip spent on average $3,501 per trip, while the average

visiting group spends $606.

In 2017, 5.4% of all visitors participated in a guided trip and spent $791 million while in

Montana, accounting for nearly a quarter of all visitor.

Water based activities including rafting/floating/canoeing/kayaking (283,600 clients) and fishing

(160,400 clients) represent the largest guided trip sectors when ranked by volume of clients.

Fishing ($76.7 million) and hunting ($55.3 million) represent the largest revenue generating trip

types for the outfitters and guides themselves. 90 and 85% of these clients, respectively, are

from out-of-state.

61% of outfitted or guided trips that were land based took place on public lands.

28% of water based guided and outfitted trips accessed the waterways through a Montana Fish,

Wildlife, and Parks Fishing Access site.

Montana’s Outfitting Industry

2018

iv

Montana’s Outfitting Industry: 2017 Economic

Contribution and Industry-Client Analysis

Executive summary

In 2017, 728,900 clients experienced Montana’s outdoors via a guided or outfitted experience. These

experiences were provided by one of roughly 1,450 different entities who offer such trips as at least a

portion of their business or through a nonprofit. Water based activities led the way in clients served,

while fishing and hunting lead the way in total revenue generated.

Outfitted Activity

Total

Clients

Served

Average

Trip Length

(Days)

Rafting/Floating/

Canoeing/Kayaking

283,600

1.09

Fishing

160,400

2.03

Day Trail/Horseback Rides

151,200

0.81

Hiking

32,100

0.93

Snowmobiling

21,200

0.84

Hunting

17,400

4.51

Wildlife viewing

12,400

0.47

Other (Backcountry Horse,

Outdoor Education,

Backpacking, Photography,

etc.)

50,600

2.04

Total

728,900

1.03

Table ES- 1. Client Volume and Trip Length.

Outfitted Activity

Total Outfitter

Revenue

Fishing

$76,742,200

Hunting

$55,295,900

Rafting/Floating/Canoeing/Kayaking

$51,068,400

Other (Backcountry Horse, Outdoor Education, Backpacking, Photography, etc.)

$29,832,700

Day Trail/Horseback Rides

$10,587,000

Wildlife Viewing

$2,820,000

Snowmobiling

$1,733,200

Hiking

$1,401,200

Total

$229,480,600

Table ES- 2. Total Outfitter Revenue, 2017.

Licensed hunting and fishing outfitters

routinely provide a wide diversity of

experiences beyond just hunting and

fishing. Outfitters licensed by the Montana

Board of Outfitters as hunting only receive

approximately 6 percent of their outfitting

revenue from non-hunting sources. Those

outfitters licensed as fishing only, receive

13 percent from non-fishing activities,

while those licensed for both collect 37

percent from non-fishing or hunting

activities. Combined, 20 percent of

revenue for board certified outfitters is

from non-fishing or hunting sources.

Montana’s Outfitting Industry

2018

v

In 2017, the $3.4 billion in spending by nonresidents in Montana produced a total economic impact of

$4.7 billion in economic output. Though only 5-6 percent of visiting groups take part in some type of

guided or outfitted experience, those who do stay longer and spend more per day.

Expenditure Category

(Average Daily Per Group)

All Visitor Groups

Visitor Groups who Hired

an Outfitter or Guide

Gasoline, Diesel

$29.12

$15.23

Restaurant, Bar

$25.38

$49.45

Hotel, B&B, etc.

$17.03

$22.25

Outfitter, Guide

$14.29

$228.50

Retail Sales

$11.27

$27.68

Groceries, Snacks

$9.08

$10.06

Licenses, Entrance Fees

$7.50

$54.85

Auto Rental

$4.57

$15.95

Rental Cabin, Condo

$3.19

$37.78

Made in MT

$2.66

$5.04

Campground, RV Park

$1.48

$3.81

Misc. Services

$1.12

$9.94

Auto Repair

$0.93

$ -

Gambling

$ 0.35

$0.17

Farmers Market

$0.14

$0.21

Transportation Fares

$0.01

$0.05

Total Daily Spending

$128.12

$480.95

Total Trip Spending

$606.01

$3,501.32

Table ES- 3. Visitor Expenditures.

Total Economic Contribution

Industry Output

$1,254,369,400

Employment (# of Jobs)

16,300

Labor Income

$453,648,000

Value Added

$658,791,500

State & Local Sales

$53,866,342

Table ES- 4. Economic Contribution of Visitors who Take Guided Trips.

1

Montana’s guided and outfitted activities are intimately entwined with the quantity and quality of

natural amenities available. This connection deepens the importance of continued accessibility and

preservation of quality public lands and waterways. Actions or events that lead to a real or perceived

degradation of the natural resource quality of the rivers or forests pose inherent threats to foundational

components of Montana’s tourism industry.

1

Note: This report displays all spending by nonresidents who participated in a guided or outfitted activity

regardless of their primary reason for visiting Montana. As such, we use the term “contribution” rather than

“impact”. Subsequently, comparison of industry output and jobs between this report and the 2007 report is not

advised.

In 2017, the 5.4% of all

visitors who took a guided

experience spent a total of

$791 million while in

Montana, accounting for

nearly a quarter of all

visitor spending.

Montana’s Outfitting Industry

2018

vi

Contents

Abstract ........................................................................................................................................................ iii

Executive summary ...................................................................................................................................... iv

List of Tables and Figures ............................................................................................................................ vii

Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 1

Purpose ..................................................................................................................................................... 1

Outfitting’s Place in the Outdoor Industry.................................................................................................... 2

Outdoor Recreation and Tourism in Montana ......................................................................................... 2

Outfitting and Guiding in US and Montana .............................................................................................. 4

Methods ........................................................................................................................................................ 6

Survey Design – Outfitters and Guides ..................................................................................................... 6

Limitations............................................................................................................................................. 6

Response Rate ....................................................................................................................................... 7

Survey Design - Clients .............................................................................................................................. 7

Response Rate ....................................................................................................................................... 8

Results ........................................................................................................................................................... 9

A Profile of Outfitters in Montana ............................................................................................................ 9

Outfitting Business Description ............................................................................................................ 9

Land Use by Outfitters ........................................................................................................................ 12

Business Operations ............................................................................................................................ 13

A Profile of Outfitted Clients in Montana ............................................................................................... 16

Respondent Demographic Characteristics .......................................................................................... 16

Guided Trip Group Characteristics ...................................................................................................... 17

Client Expenditures ............................................................................................................................. 19

Economic Contribution of Outfitted Trips in Montana ....................................................................... 19

Conclusions & Recommendations .............................................................................................................. 21

Improving Data Collection ...................................................................................................................... 22

Appendix A: Outfitter Survey Instrument .................................................................................................. 23

Montana’s Outfitting Industry

2018

vii

List of Tables and Figures

Table 1. Response Totals by Necessity to License with Montana Board of Outfitters. ................................ 7

Table 2. Nonresident Groups in which at least One Group Member Hired an Outfitter. ............................ 8

Table 3. Characteristics of the Outfitting Business. .................................................................................... 10

Table 4. Employment Profile. ...................................................................................................................... 11

Table 5. Types of Land and Water Access Used for Outfitted Trips. .......................................................... 12

Table 6. Clients and Client Days by Activity Type. ...................................................................................... 13

Table 7. Total Outfitter Revenue.. .............................................................................................................. 14

Table 8. 2017 Outfitter Expenses. ............................................................................................................... 15

Table 9. Economic Components of the Outfitting Industry. ....................................................................... 16

Table 10. Residency Comparison Between Guided Visitors and All Visitors. ............................................. 18

Table 11. Primary Reason for Visiting if on Vacation. ................................................................................. 18

Table 12. Average Daily Expenditures. ....................................................................................................... 19

Table 13. 2017 Economic Contribution of Nonresident Visitor Engaging in Guided Experiences. ............. 20

Table 14. Outfitted Group Comparison 2015-2017. ................................................................................... 20

Figure 1. Household Income Comparison of All Visitors to Those who Hired an Outfitter. ....................... 17

Montana’s Outfitting Industry

2018

1

Introduction

To provide a current, detailed cross-section of the outfitting industry in Montana, this report updates

and expands upon a 2007 Montana Outfitting Industry report produced by the Institute for Tourism and

Recreation Research (ITRR).

2

To accomplish this, we utilized two primary data sources; the first is based

on a survey of outfitting and guiding businesses and the other draws from nonresident visitors who

indicated they hired an outfitter or guide during their Montana visit. In line with the previous report,

the information is presented in four sections. The first section is a review of the outdoor recreation

industry in the US, with a particular emphasis on the outfitting and guiding industry in Montana. The

second section contains the results of the outfitter business survey including an estimate of the number

of outfitters, employment data, types of trips, number of clients, revenues and expenses. This

assessment is the result of an online survey, delivered via the Qualtrics platform, to all known outfitters

in the spring of 2018 regarding their business activity in 2017. The third section of this report contains

an assessment of people who participate in guided trips in Montana – the clients. This assessment was

drawn from those respondents in ITRR’s annual nonresident survey who indicated they hired an

outfitter or guide of any type. Finally, the fourth section contains an analysis of the economic

contribution of the outfitting industry on Montana. It combines the total trips estimated by all outfitters

and the client-stated expenditures by utilizing IMPLAN’s input-output model.

3

Purpose

The purpose of this study is to assess the current structure of the outfitting and guiding industry through

an analysis of 1) the economic contribution of nonresident client expenditures, 2) industry supply and

diversity of outfitted and guided experiences, and 3) a thorough characterization of the attributes of

both the clients and outfitters within the industry.

Objectives:

1. To estimate the number of outfitters and guides working in the state of Montana across all

outdoor recreation activities.

2. To inventory the number, type, and duration of trips provided by outfitters and guides.

3. To identify client demographics and outfitted trip characteristics.

4. To estimate the economic contribution of the Montana outfitting/guiding industry on

Montana’s economy.

5. To compare similarities and differences between the 2006 and 2017 outfitting industry and

clients in Montana.

2

Nickerson, Norma P.; Oschell, Christine; Rademaker, Lee; and Dvorak, Robert, "Montana's Outfitting Industry:

Economic Impact and Industry-Client Analysis" (2007). Institute for Tourism and Recreation Research Publications.

212. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/itrr_pubs/212

3

IMPLAN Group LLC, (DATE of our program). IMPLAN System (data and software), Huntersville, NC

www.IMPLAN.com

Montana’s Outfitting Industry

2018

2

Outfitting’s Place in the Outdoor Industry

In November of 2016, The United States Department of Agriculture released a report titled Federal

Outdoor Recreation Trends: Effects on Economic Opportunities.

4

In the report, the USDA analyzed 17

different outdoor recreation activities, broken down into seven categories. Their goal was to not only

identify recent trends in outdoor recreation, but also to generate projections for outdoor recreation

activity in the US for the year 2030. This report piggybacked on a prior USDA analysis completed in

2012.These analyses were primarily based on the National Survey on Recreation and the Environment

(NRSE). The NRSE was a general population telephone survey of people 16 years or older designed to

measure participation in outdoor recreation activities and people’s environmental behaviors and

attitudes.

5

The USDA reports found that from 1999-2009, the number of people who participated in

nature-based outdoor recreation grew by 7.1 percent over the decade and the number of activity days

grew by about 40 percent. In addition, the clear growth areas that were identified were activities

oriented towards viewing and photographing nature, both in terms of the number of participants and

activity days of participation. Other areas of outdoor recreation that exhibited clear growth were Off-

Highway Vehicle (OHV) usage, which increased by 34 percent during the same period. Several physically

challenging activities, such as kayaking, snowboarding, and surfing, also had relatively large increases in

participation throughout the same period.

As of February 2018, the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) has begun measuring and publishing the

economic contribution outdoor recreation makes to US Gross Domestic Product (GDP). This information

is intended to add to the public understanding of the outdoor recreation economy and to inform

decision-making by policy makers, businesspeople, and the managers of public lands and waters.

6

For

the 2016 report, the BEA separated outdoor recreation activities into three main categories:

“conventional core activities” (things like bicycling, hiking, hunting), “other core activities” (like

agritourism, outdoor festivals, and even amusement parks), and “supporting activities” (travel,

government, and construction).

7

In total, the Value Added by Industry (the industry’s contribution to

the US economy, or GDP) in 2016 accounted for $373.7 billion or 2 percent, of overall GDP. Since 2012,

the Value Added by Industry has increased by $59 billion or 18.77 percent. Additionally, the Gross

Output by Activity (a measure of outdoor recreation-related sales) accounted for $673.1 billion to the

US economy.

8

Outdoor Recreation and Tourism in Montana

In regards to Montana, tourism and outdoor recreation have been identified as one of the main

contributors to the recent economic success of the state. According to the latest report issued by the

Outdoor Industry Association (OIA), outdoor recreation in Montana accounted for $7.1 billion in

consumer spending, 71,000 direct jobs, $2.2 billion in wages and salaries, and $286 million in state and

4

Eric M. White et al., Federal Outdoor Recreation Trends: Effects on Economic Opportunities, technical paper no. PNW-GTR-945,

The United States Department of Agriculture, November 2016, , accessed June 25, 2018.

5

Cordell, H. Ken. 2012. Outdoor recreation trends and futures: a technical document supporting the Forest Service 2010

RPAAssessment. Gen. Tech. Rep. SRS-150. Asheville, NC: U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Southern Research

Station, 167 p.

6

US Department of Commerce, BEA, and Bureau of Economic Analysis, "Bureau of Economic Analysis," U.S. Bureau of Economic

Analysis (BEA). Accessed June 27, 2018, https://www.bea.gov/outdoor-recreation/.

7

Frederick Reimers, "Government Puts Outdoor Industry Size at $373 Billion," Outside Online, February 15, 2018, , accessed

June 27, 2018, https://www.outsideonline.com/2281581/government-puts-outdoor-industry-size-673-billion.

8

U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis. 2018. “Outdoor Recreation Satellite Account: Prototype

Statistics for 2012–2016.” News release, February 14.

Montana’s Outfitting Industry

2018

3

local tax revenue in 2017.

9

The OIA also stated that spending on outdoor recreation in Montana exceeds

the value of statewide agricultural crop, livestock, and poultry products sold ($4.3 billion).

10

In addition to the economic contribution outdoor recreation generates for Montana residents, tourism

by nonresident visitors creates an additional economic boost to the state. According to information

collected by the Institute for Tourism and Recreation Research (ITRR), nonresident visitors to the state

accounted for $3.04 billion in total expenditures for 2016.

11

,

12

Although these numbers are expected to continue to increase over the next few years,

13

there are

contributing factors that could limit or deter visitors from choosing Montana as a destination. In 2017,

Montana endured an extended wildfire season that negatively impacted several businesses associated

with tourism or outdoor recreation. In a 2018 ITRR report, 56 percent of tourism businesses said

wildfires decreased their business volume, while 26 percent had no change in volume due to fires.

Twelve percent experienced an increase in volume, many indicating it was because they housed

firefighters. Furthermore, 25 percent of businesses had to cancel or postpone an event due to fires or

smoke and thirteen percent had to cancel guided trips.

14

If this trend of prolonged and damaging fire

seasons continues, many of the businesses surveyed expressed concerns over their ability to adapt. Of

the 135 respondents who wrote in answers to what their businesses could do to adapt to the wildfire

season, 40 of the respondents said, “There is nothing I can do.” Of the 141 different people who wrote

in their views on what the tourism industry could do to adapt to wildfire season, 36 of the respondents

said, “there was nothing the industry could do; that Mother Nature will do what it will do; or they simply

don’t know what adaptations the industry could make.”

In addition to the complications that arise surrounding fire season, rivers in Montana have experienced

their own battles with Mother Nature in recent years. In a 2016 White Paper, ITRR examined the

economic contributions of the Yellowstone River to Park County in order to understand the effects a

temporary closure (2-3 weeks depending on the particular stretch of water) had on the local economy.

In August of 2016, a temporary emergency closure of all water-based recreation was issued on 183 miles

of the Yellowstone River and its tributaries between the northern Yellowstone National Park boundary

near Gardiner, MT and Laurel, MT. The closure was instigated by the presence of an invasive parasite

known to cause proliferative kidney disease (PKD) that was thought to have caused the death of

thousands of mountain whitefish. While the presence of such a parasite is not universally a cause for

such action, a number of confounding conditions added to the severity of the situation and the mortality

of the fish. Low river flows, elevated water temperatures, and recreational pressure on the fisheries all

added to the stress on the fish and pose longer term impacts if not effectively addressed. Montana’s

Fish, Wildlife and Parks (FWP) stated at the time that a major goal of the closure was to minimize stress

9

Outdoor Industry Association, "Montana", accessed June 27, 2018:

https://outdoorindustry.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/OIA_RecEcoState_MT.pdf .

10

U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis. 2018. “Outdoor Recreation Satellite Account:

Prototype Statistics for 2012–2016.” News release, February 14.

11

Grau, Kara, "2016 Nonresident Visitation, Expenditures & Economic Impact Estimates" (2017). Institute for

Tourism and Recreation Research Publications. 358. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/itrr_pubs/358

12

NOTE: The OIA and the ITRR reports are not additive. Significant overlap between the reports exist, thus adding

the two together would include double counting.

13

Sage, Jeremy L., "Montana Tourism Trends and Forecasting" (2018). Institute for Tourism and Recreation

Research Publications. 370. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/itrr_pubs/370

14

Nickerson, Norma P., "2017 Trends & 2018 Outlook: Montana Tourism Business Survey" (2018). Institute for

Tourism and Recreation Research Publications. 364. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/itrr_pubs/364

Montana’s Outfitting Industry

2018

4

to infected fish. Angling and other recreation adds to the stress already felt due to the low water levels

and high temperatures, thus removing the human based stressors is believed to increase their survival

to the following year.

15

Should the need to increasingly curtail or restrict water-based recreation arise,

significant economic impacts are likely to be felt across the region; total direct annual spending by

anglers on the Upper Yellowstone River accounted for $69.9 million in 2013.

16

Serving as such a large

contributor to the local economy, it is easy to see how such a closure, or the potential of one, would

negatively affect the economic potential of resource dependent businesses moving forward, such as

outfitters and guides.

This sentiment was echoed by the previously mentioned 2016 USDA report on outdoor recreation

trends. In the report, the USDA outlined their recreation projections for 2030 based on four contributing

factors: demographic changes, economic factors, land use, and climate factors (such as climate change).

In their projection models, climate variables were added to assess whether participation and

participation intensity were sensitive to climate effects. Overall, 14 of 17 activities showed average

declines in total days of participation when accounting for climate change. The percentage point decline

was greatest for three activities: snowmobiling, undeveloped skiing (cross-country skiing, snowshoeing),

and floating (canoeing, kayaking, rafting), accounting for average net decreases of 39, 36, and 9

percentage points, respectively.

17

If these projections are accurate, they could have a potential negative

impact on the economic outlook for year-round Montana tourism moving forward.

Outfitting and Guiding in US and Montana

As a component of outdoor recreation, hunting, fishing, and wildlife watching are significant

contributors to the success of the outdoor recreation economy. More specifically, outfitting and guiding

comprises a significant portion of the hunting, fishing, and wildlife viewing economy. In 2016, the US

Fish and Wildlife Service and the US Census Bureau found that guide fees for fishing, hunting, and

wildlife watching were $924.9 million, $658.4 million, and $108.3 million, respectively.

18

These figures

do not include other trip costs associated with these activities, such as pack trip or package fees, public

and private land use fees, equipment rental, boating costs, bait, ice, and heating and cooking fuel. If all

these costs are compiled, they total roughly $11.7 billion, or $297 per person, in expenditures.

In Montana, outfitting and guided activities have also significantly contributed to the local economy.

Such guided or outfitted activities in Montana include: hunting, fishing, hiking, backpacking, wildlife

viewing, rafting, horseback riding, and snowshoeing, just to name a few. According to information

collected by ITRR, outfitter and guided expenditures by nonresident travelers in 2017 accounted for

$373,780,000, or 11 percent of total nonresident visitor expenditures. The economic contribution made

by the outfitting and guiding industry has increased significantly, even in recent years. As of 2017,

outfitter and guided expenditures by nonresident travelers eclipsed that of retail sales, groceries and

snacks, and licenses/entrance fees, trailing only the expenditures made for fuel, restaurants/bars, and

15

Sage, Jeremy L., "Economic Contributions of the Yellowstone River to Park County, Montana" (2016). Institute

for Tourism and Recreation Research Publications. 346. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/itrr_pubs/346

16

FWP, 2015. Montana Statewide Angling Pressure 2013. Angling pressure in angler days by drainage by lake or

stream shown in Tables 5, 7 and 9.

17

Eric M. White et al., Federal Outdoor Recreation Trends: Effects on Economic Opportunities, technical paper no.

PNW-GTR-945, The United States Department of Agriculture, November 2016, accessed June 25, 2018.

18

U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and U.S. Department of Commerce, U.S. Census

Bureau. 2016 National Survey of Fishing, Hunting, and Wildlife-Associated Recreation.

Montana’s Outfitting Industry

2018

5

hotel/motels.

19

These figures indicate the important economic contribution nonresident visitors make

to the state, particularly on guided or outfitted outdoor recreation activities.

Although these figures have increased over time, recreation management plans have been enacted by

FWP on several rivers throughout the state to help combat issues of overcrowding perceived by

Montana residents. Rivers like the Big Hole, Bitterroot and West Fork of the Bitterroot have seen

management plans enacted that limit the number of guides allowed on the river, in addition to

limitations on where those guides can operate each day during the peak season. Currently, Montana

FWP is working on implementing a recreation management plan on the Madison River to deal with

similar issues.

According to information collected by Montana FWP, since 2003, significant increases in angling

pressure have been observed on the Madison. Over the last four years, the Madison has seen a steep

increase in use, doubling from 88,000 to 179,000 angler days. In 2016, Montana FWP conducted a mail

in survey focusing on angler satisfaction. Data were collected from 1,335 residents of Montana and

1,545 non-residents. The survey questioned both residents and non-residents on several factors related

to their overall angling experience in two reaches of the upper Madison River- Hebgen Dam to Lyons

Bridge and Lyons Bridge to Ennis Reservoir. The most striking data indicates that 54 percent of residents

and 30 percent of non-residents feel that the number of float users from Lyons Bridge to Ennis Lake is

either “Very Unacceptable” or “Unacceptable”.

20

Perhaps the first example of regulating guided activities was the I-161 initiative passed by the voters of

Montana, 53.8 percent to 46.2 percent in 2010. I-161 was a citizen-initiated state statute to increase

nonresident big game license fees and abolish outfitter-sponsored licenses. Until then, hunting outfitters

were guaranteed a certain number of licenses for their clients. Clients paid almost double the price of a

nonresident fee for that guarantee. Ultimately, Montana FWP lost revenue from nonresident licenses

until 2017. The intent by many backers of I-161 was to open private lands to hunting by residents but it

appears the opposite affect happened.

21

If this type of pushback continues against guided or outfitted outdoor recreation experiences,

particularly from residents, other rivers or areas of the state may see management plans enacted to

help preserve the experience for those local individuals recreating. This could create a plateauing effect

on the economic contributions of guides and outfitters to expenditures by nonresident visitors to

Montana because their economic potential will essentially be capped. It is difficult to say with any

certainty that this effect could take place anytime soon, if at all, but it appears to be something that

those involved in the outdoor recreation community, particularly angling, should take note of moving

forward.

19

Grau, Kara, "2017 Nonresident Visitation, Expenditures & Economic Impact Estimates" (2018). Institute for

Tourism and Recreation Research Publications. 367. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/itrr_pubs/367

20

Montana Fish Wildlife and Parks. "Madison River: Draft Recreation Management Plan- Environmental

Assessment." April 19, 2018. Accessed June 27, 2018.

https://bloximages.chicago2.vip.townnews.com/bozemandailychronicle.com/content/tncms/assets/v3/editorial/7

/9a/79a8cea4-b6f5-5b21-aecb-18a05d8fcb0a/5acd4edbe5525.pdf.pdf

21

Tipton, Michael and Nickerson, Norma P., "Assessment of Hunter Access on Montana Private Lands" (2011).

Institute for Tourism and Recreation Research Publications. 210. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/itrr_pubs/210

Montana’s Outfitting Industry

2018

6

Methods

This report approaches the outfitting and guiding industry of Montana from two perspectives: that of

both the businesses and the clients. Each group provides a unique, and complementary, information set

about the influence of the industry on the state. Their combined perspectives permit an assessment of

the overall economic contribution to the state. Both populations were separately surveyed. Client

information was drawn from individuals indicating they hired an outfitter/guide on ITRR’s survey of

nonresident visitors to Montana.

22

The outfitters and guides themselves were surveyed in the spring of

2018. The timing of the survey of outfitters and guides sought to roughly coincide with timing of federal

income tax filing, such that needed information would be more readily available. Each survey

methodology is detailed below.

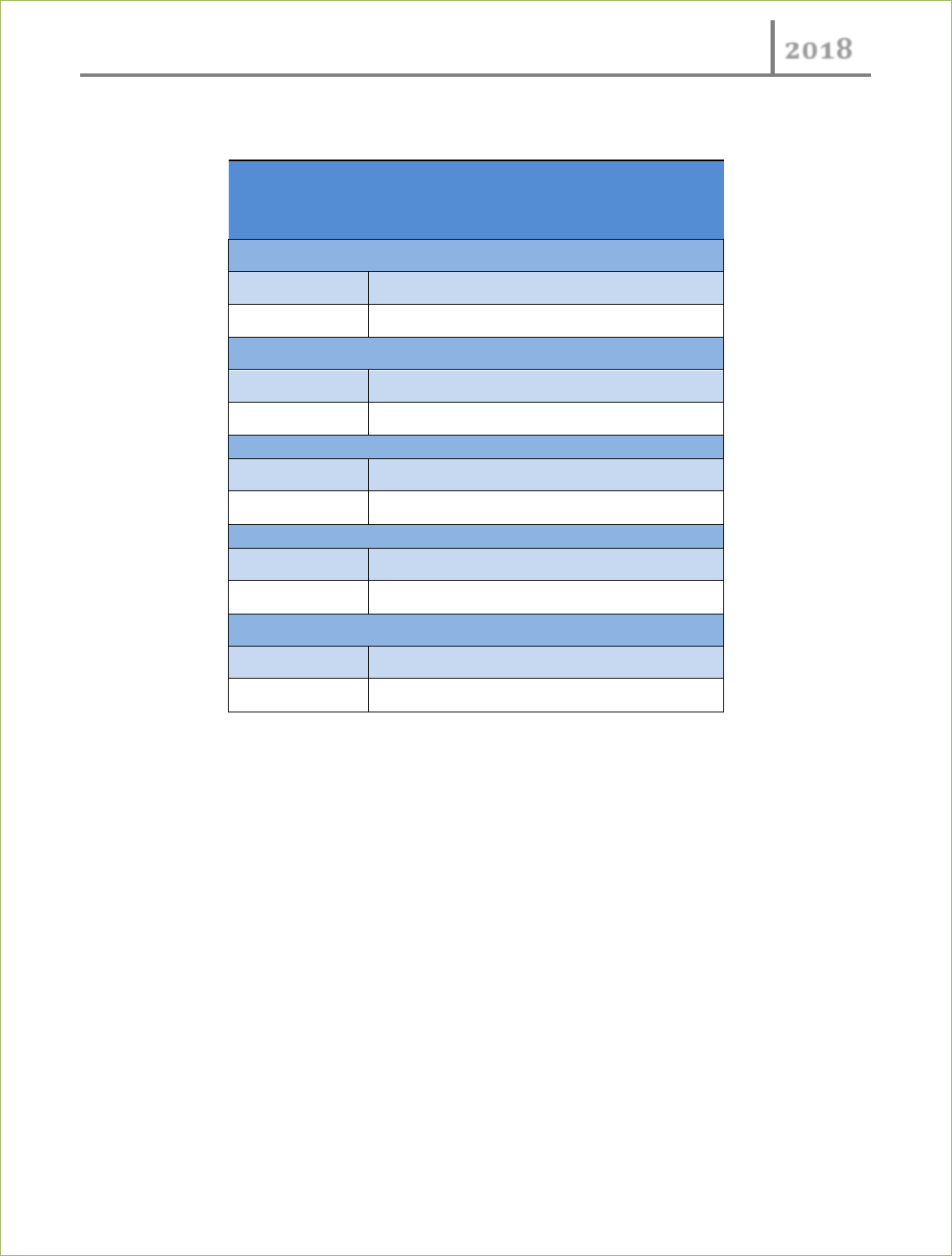

Survey Design – Outfitters and Guides

To address the outfitter and guide-side objectives of this study, a survey instrument was designed using

the previous 2007 ITRR outfitter survey as an initial base. Rather than a paper survey mailed to the

businesses, the instrument was created in Qualtrics, an online survey platform, and delivered to the

business email on record. The email request to complete the survey was sent to all known outfitters and

guides thought to be operating in the state, and for whom a reliable email address could be readily

obtained. The realm of “known”, also known as the sampling frame, was derived from either registration

lists or records of special use permits from the following sources:

The Montana Board of Outfitters (MBO);

23

The Montana Office of Tourism and Business Development (MOTBD);

The US Forest Service (USFS).

The combined and cleaned list resulted in a distribution of the survey to 1,257 email addresses. Of those

emails sent, 167 were found to be undeliverable, resulting in a final distribution of 1,090 surveys. In

addition to the announcements of the survey sent out by ITRR, the two primary hunting and fishing

outfitter associations (Montana Outfitter and Guide Association (MOGA) and the Fishing Outfitters

Association of Montana (FOAM)) included announcements of the forthcoming survey in their

newsletters and actively encouraged their members to participate. In addition to the direct email sent

out by ITRR, both MOGA and FOAM included the survey link in emails to their membership. Their

membership lists overlap with the lists generated from the Montana Board of Outfitters.

Limitations

While we can be reasonably confident that nearly all, if not all, hunting and fishing outfitters with valid

email addresses were provided an opportunity to complete the survey, less confidence is warranted in

other types of outfitting and guiding activities. This reduced confidence stems from the lack of any

formal requirements on the part of these businesses to register with any state or other licensing board.

As such, those businesses contacted are limited to those who voluntarily register with MOTBD or

provided services on federal lands requiring a use permit. However, given the volume of registered

22

Grau, Kara, "2017 Nonresident Visitation, Expenditures & Economic Impact Estimates" (2018). Institute for

Tourism and Recreation Research Publications. 367. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/itrr_pubs/367

23

Only fishing and hunting outfitters and guides are required to be registered with the MBO.

Montana’s Outfitting Industry

2018

7

businesses in comparison to observable data from business reference lists

24

, we believe we have

captured the majority of providers of outfitting and guiding services. Additionally, as will be reported in

detail later, many of those who are fishing and hunting outfitters also provide other guiding services,

which further broadens the scope of reach to these sectors.

Response Rate

In total, 388 surveys were completed for a response rate of 35.6 percent. Of those completed surveys,

252 came from the direct email from ITRR, 116 came from the link provided by FOAM, and the

remaining 20 came from the link provided by MOGA. Eighty-nine percent of respondents indicated they

provided some type of outfitting or guiding service in 2017. This leaves 11 percent of respondents

indicating they did not provide such a service in 2017. In addition to those indicating no services were

provided, multiple calls or emails to ITRR by recipients (approximately 7) of the emailed survey indicated

they were unsure of why they were on this list. Upon further discussion, all of these individuals had

obtained a special use permit from the USFS; however, their use did not align with outfitting and

guiding. As shown in Table 1, the vast majority of respondents were licensed by the MBO either as

outfitters (n=122), guides (n=81), or both (n=94).

Table 1. Response Totals by Necessity to License with Montana Board of Outfitters.

Frequency

Valid

Percent

I am a Board of Outfitters licensed guide in Montana (applies to hunting

and fishing only).

81

25%

I am a Board of Outfitters licensed outfitter in Montana (applies to hunting

and fishing only).

122

37%

I am both a Board of Outfitters licensed guide and outfitter in Montana

(applies to hunting and fishing only).

94

29%

I am an outfitter/guide for other types of activities (not hunting or fishing).

32

10%

Total Responses

329

100%

Missing

59

Total

388

Survey Design - Clients

To address the client-side objectives of the study, data specific to nonresident visitors who indicated

they hired an outfitter or guide was drawn from the quarterly nonresident visitor survey. This annually

conducted survey began in 2009, and has been continuously conducted since. (See footnote for data

collection methods, analyses, and limitations for the nonresident travel survey.

25

) Intercepted

nonresidents are asked on-site (Front End Survey) whether they took a guided or outfitted trip during

any portion of their trip while in Montana. Respondents indicating such an activity were further asked

where the trip took place and how much they spent. Additionally, respondents were asked if they would

be willing to provide additional information via a paper survey that may be mailed back or filled out

24

Reference USA accessed and reviewed via the Montana State Library system. Businesses in Montana with NAICS

codes of 713990 (All other amusement & recreation activities) and 487210 (Scenic & sightseeing transportation,

water) were reviewed and compared against obtained email lists.

25

Nonresident travel survey and visitation and spending estimation models:

http://itrr.umt.edu/files/NonresTravelSurvey-Methods-Analysis.pdf

Montana’s Outfitting Industry

2018

8

online. Within this additional (Back End) survey, respondents are provided an opportunity to expand

upon their activities and sites visited within the state.

Response Rate

In 2017, 11,135 front-end surveys were completed equating to 12.5 million nonresident visitors to

Montana. Of these front-end surveys, 2,565 respondents completed and satisfactorily returned the

follow-up paper survey. These sample sizes are typical of most years of data collection. Table 2 shows a

steady five to six percent of nonresident groups report at least one group member hired a guide or

outfitter during their Montana trip. Reported characteristics in the following client results section draw

from 2017 respondents.

Table 2. Nonresident Groups in which at least One Group Member Hired an Outfitter.

Year

Proportion of Respondents Hiring an Outfitter

Visitors Represented

2017

5.4% (n=132)

675,076

2016

5.3% (n=143)

651,789

2015

5.7% (n=217)

668,007

2014

5.1% (n=159)

557,913

2013

5.3% (n=151)

584,808

Montana’s Outfitting Industry

2018

9

Results

A Profile of Outfitters in Montana

This section presents a profile of Montana outfitters as they described their 2017 outfitting business.

The outfitter profile includes a basic description of Montana outfitters followed by a discussion of their

revenues and expenses.

Outfitting Business Description

In 2017, there were 1,450 identifiable businesses or individuals providing outfitting services of any type

in Montana.

26

,

27

Within this group, there were 740 known fishing and hunting outfitters who had

renewed their licenses with the MBO. Of these outfitters, 340 were licensed as fishing only, 200 as

hunting only, and 200 licensed for both hunting and fishing. There were an additional 25 new outfitter

licensees. Additionally, 1,500 guides renewed their licenses with the MBO, and 300 new guides became

licensed.

On average, outfitters have been in business 18 years and expect to continue in business for an average

of 16 more years (Table 3). The “average” outfitter took 172 clients on an outfitted trip in 2017. Three

outfitters exceeded 10,000 clients served during 2017.

28

After adjusting for the weighted average

between the different categories of guided activities, outfitters estimated that 63 percent of their clients

were nonresidents of Montana. A further analysis of where clients were from appears in the “Outfitted

Clients” section.

26

Additional entities were identified via comparison of known lists with recorded business listings found in

ReferenceUSA database.

27

1,450 should be considered an estimate of the number of active outfitters of any type in the state. Given the

diversity of outfitting businesses and business structure in the state, an exact number is not readily identifiable. In

trying to assess the total number of businesses, we identified that the businesses are classified in no less than 12

different Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) Codes. These include: River Trips, Fishing Parties, Boat-Excursions,

Raft Trips, Guide Service, Outfitter, Hunting Trips, and Amusement & Recreation.

28

Inputs into the Qualtrics survey platform were capped at 4 digits, resulting in slightly lower estimates in regards

to the number of clients and number of client days in comparison to the 2007 report.

Montana’s Outfitting Industry

2018

10

Table 3. Characteristics of the Outfitting Business.

All Outfitting

Years in the business of outfitting

Mean

17.62 years

Range

1 - 70 years

More years expecting to continue to outfit

Mean

16.35

Range

1– 99 years

Number of clients

Mean

172

Range

0 - 9,999*

Number of client days

Mean

207

Range

0 - 9,999*

Percent of clients from out-of-state

Mean

63%

Range

0-100%

* Inputs into the Qualtrics survey platform were capped at 4

digits, resulting in slightly lower estimates in regards to the

number of clients and number of client days in comparison to the

2007 report.

The outfitting business primarily consists of small entrepreneurs. Just over 43 percent of reporting

businesses were organized as a Sole Proprietorship, while nearly 32 percent were Limited Liability

Companies (LLC). The remaining respondents were comprised of S Corps, Partnership Corporations, and

Non-Profits. Nearly 50 percent of all labor hired by responding outfitters and guides were hired as

contract laborers. Guides are typically hired as independent contractors by the outfitter. The average

outfitter held 4.8 contractors annually. The next closest category of labor type was that of employees

who were hired full time for less than 150 days, which made up 25 percent of all hires with an average

of 3.3 hires per outfitter. Listed below in Table 4 are the remaining categories of employment type from

which outfitters and guides generally categorize their hires. All categories below other than “Hired as

contract labor” are employment figures that exclude contract labor hires in order to avoid any possibility

of double counting employees.

Montana’s Outfitting Industry

2018

11

Table 4. Employment Profile.

Contract Labor

Mean # of Contractors

4.8

Range of Contracted Laborers

0-80

% with Contract Laborers (N*=224)

0 Contractors

38%

4 Contractors

5%

1 Contractor

8%

5 Contractors

7%

2 Contractors

5%

6 Contractors

6%

3 Contractors

5%

7 or more Contractors

26%

Full Time - Year Round Employees (>150 days)

Mean # of Full Time-Year Round

0.8

Range of Full Time-Year Round

0-15

% with Full Time-Year Round Employees (N=175)

0 Employees

76%

4 Employees

2%

1 Employees

7%

5 Employees

1%

2 Employees

9%

6 Employees

1%

3 Employees

2%

7 or More Employees

2%

Full Time - Seasonal Employees (<150 Days)

Mean # of Full Time-Seasonal

3.3

Range of Full Time-Seasonal

0-120

% with Full Time-Seasonal Employees (N=181)

0 Employees

72%

4 Employees

3%

1 Employees

4%

5 Employees

2%

2 Employees

6%

6 Employees

2%

3 Employees

2%

7 or More Employees

9%

Part Time - Year Round Employees (>150 Days)

Mean # of Part Time-Year Round

0.3

Range of Part Time-Year Round

0-15

% with Part Time-Year Round Employees (N=172)

0 Employees

90%

4 Employees

1%

1 Employees

3%

5 Employees

1%

2 Employees

3%

6 Employees

1%

3 Employees

0%

7 or More Employees

1%

Part Time - Seasonal Employees (<150 Days)

Mean # of Part Time-Seasonal

2.1

Range of Part Time-Seasonal

0-40

% with Part Time-Seasonal Employees (N=183)

0 Employees

63%

4 Employees

2%

1 Employees

8%

5 Employees

2%

2 Employees

6%

6 Employees

5%

3 Employees

4%

7 or More Employees

9%

N=number of respondents completing specified labor force question.

Montana’s Outfitting Industry

2018

12

Land Use by Outfitters

Outfitted trips occur across a wide variety of lands. Forty-five percent of outfitters and guides stated

that their outfitting/guiding involved land based activities. Sixty-one percent of outfitters and guides

stated their land based guiding days took place on public land followed by 32 percent who guide on

private land not personally owned. Of those guided trips that took place on public land, the usage rates

for each land type are displayed below in Table 5, with US Forest Service land representing the highest

usage rate at 32 percent.

In terms of water-related trips, 79 percent of responding outfitters and guides disclosed that their

outfitting/guiding activities involved Montana waterways. Of those guided trips that took place on

Montana waterways, the usage rates for each type of waterway are displayed below in Table 5, with

Montana FWP fishing access sites representing the highest usage rate at 28 percent.

Table 5. Types of Land and Water Access Used for Outfitted Trips.

Proportion of Land Based Outfitted Trips on Public

Lands by Ownership

US Forest Service

32%

US Bureau of Land Management

20%

Montana Department of Natural

Resources & Conservation

13%

Montana Fish, Wildlife, & Parks

11%

National Park Service

11%

Other State Land

5%

Other Federal Land

3%

US Fish & Wildlife Service

3%

Other Local Government

1%

Proportion of Water Based Outfitted Trips by

Ownership Access Type

Montana Fish, Wildlife, & Parks

Fishing Access Site

28%

Federal Land Access Site

18%

Water Access Through Private

Property

16%

Local/County Public Water Access Site

14%

Other State Land Water Access Site

12%

A Montana State Park Boat Launch

10%

Other

2%

Montana’s Outfitting Industry

2018

13

Business Operations

Ninety-one percent of all reported clients are involved in rafting/floating/canoeing/kayaking, horseback

riding, fishing, hiking, snowmobiling, or hunting. The total number of guided clients in 2017 was

728,900 while the total number of guided client days was 918,500 (Table 6). Outfitters and guides

involved in hunting and fishing must be licensed by the Montana Board of Outfitters (MBO). Licensees

may be registered in either fishing, hunting, or both. These outfitters and guides routinely engage in

providing other types of guided activities in addition to their licensed activities. MBO licensed outfitters

served nearly half of all outfitted trips in 2017; 49 percent. Those that are licensed in both served the

majority of clients in both snowmobiling and day trail/horseback rides.

Table 6. Clients and Client Days by Activity Type.

Outfitted Activity

Total

Clients

Served

Proportion of

all Outfitted

Clients

Total

Client

Days

Average

Trip Length

(Days)

Rafting/Floating/

Canoeing/Kayaking

283,600

39%

311,200

1.09

Fishing

160,400

22%

260,800

2.03

Day Trail/Horseback Rides

151,200

21%

120,400

0.81

Hiking

32,100

4%

29,700

0.93

Snowmobiling

21,200

3%

17,000

0.84

Hunting

17,400

2%

76,000

4.51

Wildlife viewing

12,400

2%

5,900

0.47

Other (Backcountry Horse,

Outdoor Education,

Backpacking, Photography,

etc.)

50,600

7%

97,500

2.04

Total

728,900

100%

918,500

1.03

Altogether, outfitted activities in Montana combined to total $229,480,600 in gross revenue to the

outfitters for 2017 (Table 7), for an average of $158,000. Hunting and fishing outfitting revenues

comprise 58 percent of all outfitted revenue. Additionally, large majorities of both hunting (85 percent)

and fishing (90 percent) clients are from out-of-state. Outfitters licensed by the MBO as hunting only

receive approximately 6 percent of their outfitting revenue from non-hunting sources. Those outfitters

licensed as fishing only receive 13 percent from non-fishing activities, while those licensed for both

collect 37 percent from non-fishing or hunting activities. Combined, 20 percent of these outfitters’

outfitting revenue is from non-fishing or hunting sources.

29

29

Identified revenue sources only account for actual outfitting activities. Revenue collected from other sources is

not included here (e.g. Fly shops).

Montana’s Outfitting Industry

2018

14

Table 7. Total Outfitter Revenue..

Outfitted Activity

Total Outfitter

Revenue

Fishing

$76,742,200

Hunting

$55,295,900

Rafting/Floating/Canoeing/Kayaking

$51,068,400

Other (Backcountry Horse, Outdoor Education, Backpacking, Photography, etc.)

$29,832,700

Day Trail/Horseback Rides

$10,587,000

Wildlife Viewing

$2,820,000

Snowmobiling

$1,733,200

Hiking

$1,401,200

Total

$229,480,600

In 2017, the average outfitting business encumbered $146,300 in expenses on employees, contractors

and other inputs to their production (Table 8). Within Table 8, all expenses except for payroll comprise

the intermediate expenditures shown in Table 9. Payroll, proprietor income, other property income, and

tax on production and imports make up the value added components of the total $229 million in

production value.

30

Expenses paid for by outfitters vary from an average low of $1,900 for insurance to an average high of

$55,400 on payroll. As in many service industries, payroll is a major portion of a business expenses.

Outfitters pay 35 percent of their expenses to payroll, followed by another 23 percent to contracted

labor, six percent for travel related expenses and five percent for land leases.

30

Values produced in Table 8 and Table 9 are generated through a combination of survey data reported by

outfitters and industry data contained in IMPLAN.

Montana’s Outfitting Industry

2018

15

Table 8. 2017 Outfitter Expenses.

Activity

% of Total

Outfitter

Expenses

Average

Expense by

Outfitter

Payroll (not including FICA, workers’ comp., unemployment taxes)

35%

$ 55,400

Contract labor

23%

$ 36,400

Travel (food, gas, lodging)

6%

$ 7,600

Land leases

5%

$ 6,600

Food, fuel, equipment supplies

4%

$ 5,600

Legal and professional services

4%

$ 4,700

Office expenses (including utilities)

3%

$ 4,200

Repair and maintenance

2%

$ 2,100

Advertising (printing, web sites, trade shows)

1%

$ 1,800

Insurance (liability, vehicle, property)

1%

$ 1,900

Other expenses (mortgage interest, licenses, livestock, etc.)

15%

$ 20,000

Total

$ 146,300

Montana’s Outfitting Industry

2018

16

Table 9. Economic Components of the Outfitting Industry.

Output (Value of Production)

$ 229,480,700

Value Added:

31

Employee Compensation

32

$ 79,605,700

Proprietor Income

33

$ 6,336,700

Other Property Type Income

34

$ 15,493,100

Tax on Production and Imports

35

$ 5,446,300

Total Value Added

$ 106,881,800

Intermediate Expenditures

36

$ 122,598,900

NOTE: All footnoted definitions are based on those found

in IMPLAN’s glossary of terms.

A Profile of Outfitted Clients in Montana

Like all nonresident respondents, clients reporting hiring a guide or outfitter were asked about

demographic information, trip characteristics, expenses and experiences. The following descriptions

compare the typical Montana visitor to those who participate in guided activities.

Respondent Demographic Characteristics

Though respondents whose travel party took a guided trip were on average the same age, 57, as the

typical respondent, they were more likely to be male; 63 percent compared to the total average of 56

percent. Montana visitors taking part in guided or outfitted activities possess several notable differences

in comparison to the average visitor. Figure 1 identifies the first notable difference: reported household

income. Those visitors’ households who participated in some type of guided or outfitted activity in 2017

tended higher than the average visitor. Nearly a quarter of those taking a guided or outfitted trip report

a household income of more than $200,000. Similar income breakouts exist in previous years as well for

those hiring a guide or outfitter. In 2016 and 2015, proportions of visitors reporting more than $200,000

in household income was 27 percent and 24 percent respectively.

31

Value Added = The difference between an industry's total output and the cost of its intermediate inputs. It

equals gross output (sales or receipts and other operating income, plus inventory change) minus intermediate

inputs (consumption of goods and services purchased from other industries or imported); it is a measure of the

contribution to GDP made by an individual producer, industry or sector

32

Employee Compensation = Employee Compensation in IMPLAN is the total payroll cost of the employee paid by

the employer. This includes wage and salary, all benefits (e.g., health, retirement) and payroll taxes (both sides of

social security, unemployment taxes, etc.)

33

Proprietor Income = payments received by self-employed individuals and unincorporated business owners. This

income also includes the capital consumption allowance and is recorded on Federal Tax form 1040C.

34

Other Property Type Income = Represents Gross Operating Surplus minus Proprietor Income. OPI includes

consumption of fixed capital (CFC), corporate profits, and business current transfer payments (net).

35

Tax on Production and Imports = Includes taxes on sales, property, and production, but it excludes employer

contributions for social insurance and taxes on income.

36

Intermediate Expenditures = Purchases of non-durable goods and services such as energy, materials, and

purchased services that are used for the production of other goods and services rather than for final consumption.

Montana’s Outfitting Industry

2018

17

Figure 1. Household Income Comparison of All Visitors to Those who Hired an Outfitter.

Guided Trip Group Characteristics

Groups taking part in guided or outfitted activities are twice as likely to report that they are in Montana

primarily for vacation, recreation or pleasure compared to the average visitors: 72 percent versus 36

percent. The average travel group with guided activities was 2.87 people compared to all visitors who

average 2.23 people per group. Only 14 percent of guided respondents indicated they were in Montana

alone, while 29 percent of all respondents indicated such. Additionally, 37 percent of guided

respondents indicated they were a group consisting of a couple and 37 percent said their immediate

family was their group, while nine percent were with friends. Among all respondents, these proportions

change to 32, 26, and six percent respectively.

A key difference arises when considering how long visitors stay in the state on their visits. Those visitors

who took a guided trip stayed on average 7.28 nights, while the average among all visitors was 4.73

nights. This sharp difference is in part reflective of the large difference in the likelihood that those taking

guided trips are on vacation compared to the average visitor.

Visiting groups from Washington State routinely outpaced other states. In 2017, Washington residents

comprised 10 percent of visiting groups who hired a guide and 13 percent of all visitors. Looking at the

remaining nine states that make up the top ten represented states in guided visitors, Table 10 shows

that six of those ten are also in the top ten for all visitors. The remaining four drop out. This observation

suggests, particularly for states like Maryland, that these visitors have a high propensity to take outfitted

or guided trips.

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

30%

Less than

$50,000

$50,000 to

less than

$75,000

$75,000 to

less than

$100,000

$100,000 to

less than

$150,000

$150,000 to

less than

$200,000

$200,000 or

greater

All Visitors Visitors Who Hired an Outfitter

Montana’s Outfitting Industry

2018

18

Table 10. Residency Comparison Between Guided Visitors and All Visitors.

Rank by

Guided

Participation

State

Visitors

Who Hired

an Outfitter

All

Visitors

Rank of

All

Visitors

1

Washington

10%

13%

1

2

Texas

7%

3%

11

3

California

7%

6%

5

4

Minnesota

6%

4%

8

5

Wyoming

6%

5%

6

6

Oregon

5%

3%

10

7

Wisconsin

5%

2%

13

8

Illinois

4%

2%

16

9

Utah

4%

4%

9

10

Maryland

3%

1%

38

Glacier National Park tops the list for primary reason to visit Montana for both those visitors taking

guided trips and the general visiting population who are in the state for vacation, recreation, or

pleasure. Table 11 shows similarities between visitors who take guided trips and those average visitors,

across many of the potential primary reasons to visit Montana for vacation. However, there are several

notable differences, including guided visitors who are four times more likely to indicate fishing as the

primary reason compared to the average visitor. Further, 31 percent of those visiting groups who

reported hiring a guide and who indicated they fished during their trip indicate that fishing was their

primary reason for visiting the state. A third of all groups who hired a guide also fished during their trip.

Table 11. Primary Reason for Visiting if on Vacation.

Primary Attraction

Visitors

Who

Hired an

Outfitter

All

Visitors

Glacier National Park

27%

22%

Fishing

16%

4%

Yellowstone National Park

14%

18%

Ski/Snowboard

8%

3%

Mountains/Forest

6%

12%

Open Space/uncrowded

Areas

5%

13%

Lakes

4%

2%

Hunting

4%

3%

Wildlife

3%

1%

Rivers

3%

1%

Montana’s Outfitting Industry

2018

19

Client Expenditures

Visitors to Montana who took guided or outfitted trips in Montana in 2017 spent, on average, $3,501

while in the state based on the previously reported 7.28 average nights spent (Table 12). Meanwhile,

the average visitor spent $606 on their Montana trips, based on their 4.73 average nights. The amount

and time spent by these types of visitors even out paces that of all vacationers. Vacationers as whole

spent 6.17 nights and $172.69 per day in 2017.

Table 12. Average Daily Expenditures.

Expenditure Category

(Average Daily Per Group)

All Visitor Groups

Vacationers

Visitor Groups who

Hired an Outfitter or

Guide

Gasoline, Diesel

$29.12

$23.31

$15.23

Restaurant, Bar

$25.38

$32.84

$49.45

Hotel, B&B, etc.

$17.03

$20.25

$22.25

Outfitter, Guide

$14.29

$32.05

$228.50

Retail Sales

$11.27

$12.61

$27.68

Groceries, Snacks

$9.08

$11.80

$10.06

Licenses, Entrance Fees

$7.50

$18.94

$54.85

Auto Rental

$4.57

$5.86

$15.95

Rental Cabin, Condo

$3.19

$6.55

$37.78

Made in MT

$2.66

$2.99

$5.04

Campground, RV Park

$1.48

$2.49

$3.81

Misc. Services

$1.12

$1.79

$9.94

Auto Repair

$0.93

$0.78

$0.00

Gambling

$0.35

$0.20

$0.17

Farmers Market

$0.14

$0.19

$0.21

Transportation Fares

$0.01

$0.03

$0.05

Total Daily Spending

$128.12

$172.69

$480.95

Total Trip Spending

$606.01

$1,065.50

$3,501.32

Economic Contribution of Outfitted Trips in Montana

In 2017, the $3.4 billion in spending by nonresidents in Montana produced a total economic impact of

$4.7 billion in economic output.

37

Though only 5-6 percent of visiting groups take part in some type of

guided or outfitted experience, those who do stay longer and spend more per day. In 2017, the 5.4

percent of all visitors who had a guided or outfitted experience spent a total of $791 million dollars

while in Montana, accounting for nearly a quarter of all visitor spending.

To identify the economic contribution of this spending, this report uses identical strategies employed in

ITRR’s annual nonresident study. IMPLAN’s Input-Output model allows the evaluation of commodity

37

Grau, Kara, "2017 Nonresident Visitation, Expenditures & Economic Impact Estimates" (2018). Institute for

Tourism and Recreation Research Publications. 367. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/itrr_pubs/367

Montana’s Outfitting Industry

2018

20

flows from producers to intermediate and final consumers, thus generating estimates of direct, indirect,

and induced impacts. The models are driven by final demand (spending) by nonresidents.

Given that the outfitter and guide client spending information is drawn directly from the annual

nonresident dataset, a direct comparison of the economic contribution is practical. Note that economic

contribution, rather than economic impact, is used here to discuss outfitting and guiding activities. This

specific terminology is used as we do not differentiate between those visitors who are in Montana

primarily for their guided trip versus those who were here for another reason. An economic impact

estimate would only account for those primarily here for the outfitted or guided experience. Table 13

demonstrates that more than 16,000 jobs and nearly $1.3 billion in economic output are generated via

the spending of Montana visitors engaging in guided experiences.

Table 13. 2017 Economic Contribution of Nonresident Visitor Engaging in Guided Experiences.

Direct Effect

Indirect Effect

Induced Effect

Total Effect

Industry Output

$ 711,594,800

$ 258,828,300

$ 283,946,300

$ 1,254,369,400

Employment (# of Jobs)

12,100

1,800

2,400

16,300

Labor Income

$ 297,919,300

$ 67,701,500

$ 88,027,200

$ 453,648,000

Value Added

$ 374,990,900

$ 133,015,700

$ 150,784,900

$ 658,791,500

State & Local Sales

$ 53,866,342

Sample Size Concerns

As previously noted in Table 2, the sample size in any given year ranges from roughly 130-220

respondents. Ideally, a sample of 350-400 groups participating in a guided experience would be

achieved. To minimize concerns over sample size, we can evaluate multiple years of our sample to

identify if reported values vary substantially to that of 2017. Table 14 shows that though there is more

variation evident than would be found in the full sample of all visitors, the length of stay and spending of

visitors taking guided experiences remains consistently above seven nights and $400 per day on

average. A conservative assessment of spending could utilize the weighted average results. However, we

use the 2017 numbers in order to maintain a consistent comparison against the full visitor sample. The

2017 results should be considered as the top of the range of spending and contribution estimates for

this group.

Table 14. Outfitted Group Comparison 2015-2017.

Year

Average Nights Spent

Average Daily Spending

Average Trip Spending

2015

7.73

$ 416

$ 3,217

2016

7.49

$ 451

$ 3,375

2017

7.28

$ 481

$ 3,501

Weighted Average

7.54

$ 444

$ 3,339

Montana’s Outfitting Industry

2018

21

Conclusions & Recommendations

In recent years, nonresident visitor spending on outfitters and guides has surpassed that of spending on

retail goods, making it the fourth highest spending category behind only fuel, lodging, and dining out.

This rise comes despite only five to six percent of the visiting population taking part in these activities.

This observation reiterates findings from the 2007 Montana Outfitter and Guide study characterizing the

outfitting industry as high value, low impact.

38

The high value is generated via the high average daily

spending ($481) compared to the average visitor ($128) as well as the extended length of time spent in

the state (7.28 days) compared to the average visitor (4.73 days). The low impact is a statement to the

low volume of visitors making up the high economic contribution, thus minimally affecting the states

resources compared to high volume activities.

The most obvious spending difference between visitors who engage in guided activities and the average

visitor is spending on the outfitters and guides themselves, with 48 percent of the $481 spent per day on

the outfitter or guide. Other notable differences include the breakout of lodging spending, suggesting

differing lodging habits of this subgroup compared to the entire visiting population. Where the typical

visitor spends $17.03, $3.19, and $1.48 on Hotels, Rental Cabins, and Campgrounds respectively, the

groups that hire guides during their trips spend $22.25, $37.78, and $3.81 on these same lodging types.

Rental cabin expenditures remain consistently high among this group across years (2015-2017).

The $228 per day spending by these visitors is distributed across nearly 1,500 known entities providing

guiding or outfitting services. Based on the responses garnered from the outfitters and guides

themselves, 58 percent of revenue is attributable to hunting and fishing activities. These activities

further the high value, low impact mantra, as they make up only 24 percent of the total volume of

outfitted clients. With the exception of rafting/floating and wildlife viewing, those outfitters and guides

who are also involved in hunting and fishing provide the majority of outfitted trips across a wide variety

of activities. High among these other activities are horseback rides and snowmobiling. In total, activities

outside of hunting and fishing make up 20 percent of the revenue stream for MBO licensed outfitters;

not accounting for any retail activities like fly shops.

Across many types of outfitted activities, respondents indicated a significant reliance on public lands,

with 61 percent of land based activities utilizing public lands. USFS and BLM lands led the way with 32

and 20 percent respectively of outfitted trips. When it comes to Montana’s waterways, 79 percent of

responding outfitters indicated their activities relied in some fashion on waterways. Of these

respondents, Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks’ access sites were the most frequently cited (28

percent), point of access. Tracing the relationships backwards from the point of access or use to the

outfitter whose business heavily relies on them, to the visitors who hire these guides, to the magnitude

of economic contribution attributable to these type of visitors, a valuable picture can be constructed for

the importance of continued accessibility and preservation of quality public lands and waterways.

Actions or events that lead to a real or perceived degradation of the natural resource quality of the

rivers or forests pose inherent threats to foundational components of Montana’s tourism industry.

38

Nickerson, Norma P.; Oschell, Christine; Rademaker, Lee; and Dvorak, Robert, "Montana's Outfitting Industry:

Economic Impact and Industry-Client Analysis" (2007). Institute for Tourism and Recreation Research Publications.

212. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/itrr_pubs/212

Montana’s Outfitting Industry

2018

22

Recent events in the state – Mountain White Fish die off in the Yellowstone River in 2016

39

and in excess

of 1.2 million acres of wildlands burned in 2017

40

- have already demonstrated such effects.

Improving Data Collection

As previously identified, estimates of total outfitter revenue are based on reported activities and