November 2022

PERFORMANCE AUDIT OF THE

CITY’S TOWING PROGRAM

Office of the

City Auditor

City of San Diego

Finding 1: The City should strengthen the public

oversight and transparency of the vehicle towing

program by publicly reporting on the program’s

outcomes, impacts to residents, and potential

revisions to tow policies and practices.

Finding 2: Internal oversight of the towing

program is strong and SDPD should continue to

conduct performance evaluations in compliance

with the City’s contract guide.

OCA-23-005 November 2022

Performance Audit of the City’s Towing Program

Why OCA did this study

Vehicle towing provides public benefits, such as ensuring streets are

clear for street sweeping, parking is available for all, parking rules and

laws are followed, and vehicles are registered. However, towing can

also have disproportionate impacts on vulnerable populations, such as

people who are low-income or are experiencing homelessness. For

some people, a vehicle tow may result in the permanent loss of their

vehicle, loss of employment, loss of access to education and medical

care, and other consequences.

California State law gives cities the ability to tow vehicles and permits

them to adopt additional laws and policies regulating the towing of

vehicles in their own jurisdiction. Consequently, a local government’s

policies may impact how various types of infractions are enforced.

Our audit included the following objectives:

1. Evaluate the financial, equity, and public benefit effects of the

City’s vehicle towing program, and how those effects may vary

under alternative vehicle towing policy and fee models; and

2. Determine the extent to which the City monitors and

evaluates contractor performance, in accordance with the

City’s Contract Compliance Guide, Council Policy 500-03, and

the contract.

What OCA found

Finding 1: The City should strengthen the public oversight

and transparency of the vehicle towing program by

publicly reporting on the program’s outcomes, impacts to

residents, and potential revisions to towing policies and

practices.

The San Diego Police Department (SDPD) is primarily responsible for

overseeing the City’s towing program. Per City Council Policy 500-03,

SDPD should provide annual updates regarding the City’s towing

program to City Council and the public; however, SDPD has not

provided a comprehensive update since 2013.

Council Policy 500-03 does not specify what information on the

program and towing trends should be included in a report. However,

we found several important trends and takeaways from recent towing

practices that highlight program changes and potential effects to the

City and residents. For example, we found:

• From FY2017 to FY2021, towing declined by 39 percent in the

City;

• While the number of tows has been decreasing, the number

of parking complaints has been increasing; and

• SDPD regularly benchmarks its towing and storage rates with

other local jurisdictions and the City’s rates are the lowest

compared to four other jurisdictions.

In addition, Councilmembers have expressed concern over the

impacts the towing program has on vulnerable residents. We

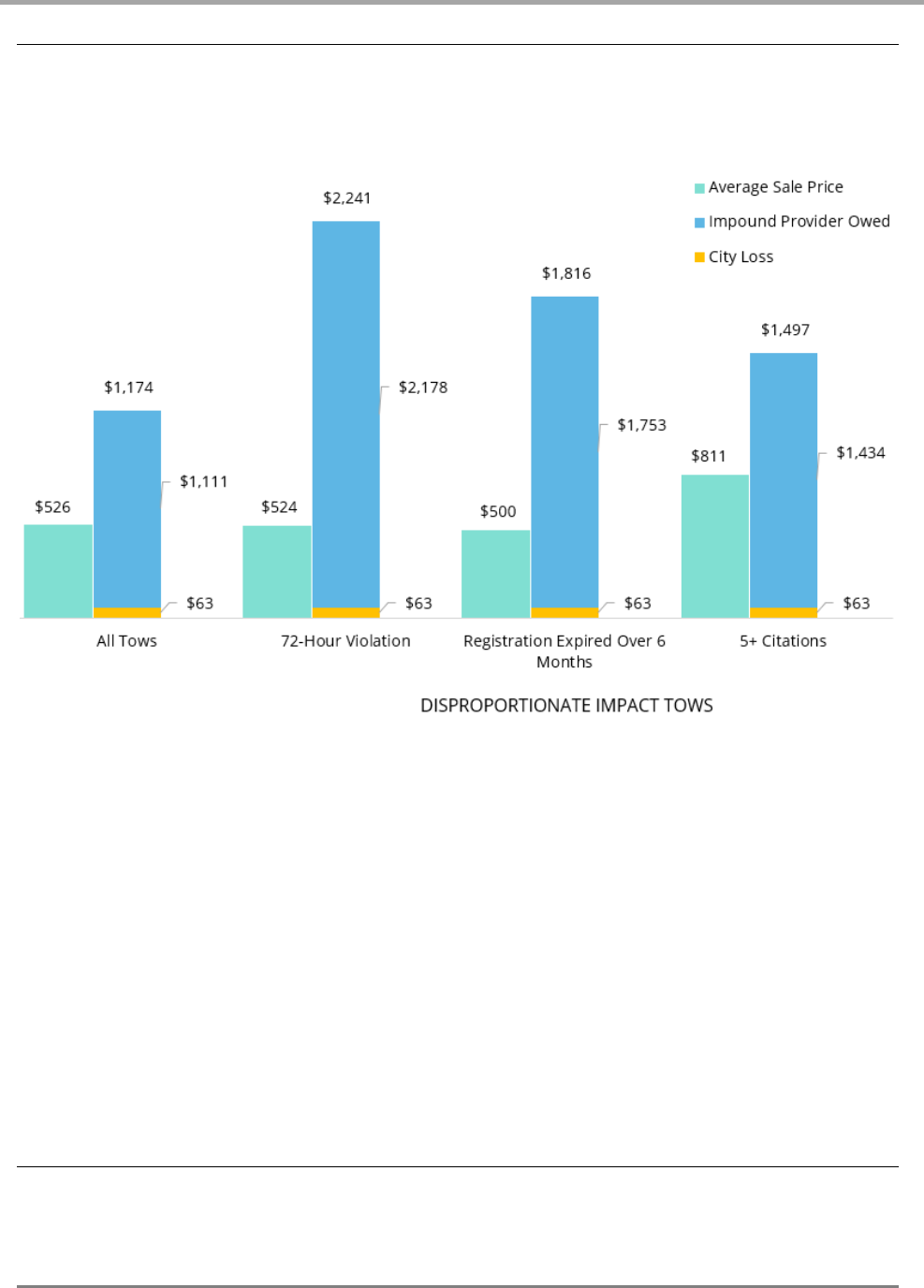

found that “Disproportionate Impact Tows”—expired registration

over six months, 72-hour parking violations, and five or more

unpaid parking citations—lead to increased likelihood of people

losing their vehicles via lien sales, which can mean unrecovered

costs for the City, the impound provider, and potentially severe

impacts on some vehicle owners, as shown in Exhibit 13.

Exhibit 13: Lien Sales May Result in Costly Impacts to Multiple Parties

Source: Auditor generated based on review of SDPD’s towing manual, SDPD’s

towing data, and Towed into Debt.

In early 2022, the City Council decided to postpone increases to

the towing program’s administrative fees. According to figures

provided by SDPD, we estimate this has resulted in a program

subsidization of approximately $1 million in foregone

administrative revenue for FY2023.

We also found that SDPD has not historically calculated and

reported the towing program’s full costs and revenues. This

information should be included in future reports to City Council.

We estimate that the City’s overall subsidy of the program is closer

to approximately $1.5 million. This is partly because approximately

27 percent of tows result in lien sales, which limit the City’s and

impound providers’ ability to recover accrued costs. We also

found that the City’s top two towing reasons—expired registration

over six months and 72-hour parking violations—are types of

Disproportionate Impact Tows. These reasons are approximately 3

to 5 times more likely to result in a lien sale, and are another

reason why the City’s towing program is not currently cost

recoverable.

Report Highlights

OCA-23-005 November 2022

Finding 1, continued

Given the City Council’s concern over the impacts of the program and

the significant financial, equity, and quality of life implications we

found exist, City leadership should evaluate its options and articulate a

policy direction on enforcement and fees for the towing program going

forward. We found other agencies have employed alternative towing

models and practices that City policymakers could consider to

balance the City’s competing goals—for example, a “text before tow”

option, updating or restructuring of fees, alternative enforcement

efforts such as “booting,” or community service instead of fees.

To inform the City’s decision making, SDPD should periodically and

publicly report on numerous aspects of the program’s financial,

equity, and quality of life implications for the City and its residents. In

addition to providing general information on the towing program and

overall trends, SDPD should inform City leadership on how the towing

program disproportionately affects vulnerable residents.

Finding 2: Internal oversight of the towing program is

strong and SDPD should continue to conduct performance

evaluations in compliance with the City’s contract guide.

We found that SDPD has implemented strong internal controls over

the towing program. The City’s third-party vendor for data

management and dispatching, AutoReturn, allows for timely

monitoring of the contracted tow and impound providers. We found

that AutoReturn accurately tracks and calculates towing fees. This

provides reasonable assurance that tow and impound providers are

following policies and procedures set by the City.

One area for improvement is contractor performance evaluations. The

City’s contract compliance guide states that SDPD should conduct

contractor evaluations on a quarterly basis and provide the evaluations

to the Purchasing and Contracting Department and to the contractors.

The guide states that contractors should be evaluated on the service

they are responsible for providing, how they are supposed to provide

it, and if they met the City’s requirements. The evaluations may be

considered in evaluating future proposals and bids for contract award.

However, from FY2019 to FY2022, we found that SDPD had not been

conducting contractor evaluations as required by the contract guide.

During the course of this audit, in late FY2022, SDPD began conducting

the evaluations, which met the contract guide’s requirements.

Specifically, SDPD evaluated its contractors based on the performance

standards within the towing manual, such as impound response times,

tow truck driver requirements, customer service to citizens, and data

entry.

Monitoring and tracking performance is key to assessing program

outcomes and ensuring contract compliance. Performance evaluations

can help improve vendor performance and may minimize the City’s risk

of contracting with previously poor-performing vendors in future

contract solicitations.

Exhibit 16: SDPD Adheres to Best Practices for Contract Monitoring in Its

New Vendor Performance Monitoring Forms but had Not Yet Shared

Vendor Performance Forms with P&C Until FY2023

Source: Auditor generated based on the OCA’s 2015 Performance Audit of Citywide

Contract Oversight and SDPD’s Quarter 1 FY2023 Compliance Evaluations.

What OCA recommends

We make 4 recommendations to address the issues outlined

throughout the report. Key recommendation elements include:

• SDPD should present a comprehensive report on the

towing program’s operations to the Public Safety and

Livable Neighborhoods Committee and/or City Council

prior to each of the City’s comprehensive user fee

studies, as well as prior to issuing or renewing an RFP for

relevant towing and/or impound contracts.

• Prior to presentation of the next towing program update,

SDPD should work with City leadership to present a new

or updated Council Policy 500-03 for City Council’s

approval. This policy should outline specific information

that should be included in the report.

• SDPD should solicit, compile, and report information to

City Council on potential policy options for the towing

program, with input from other City departments such as

City Treasurer’s, Homelessness Strategies, and others.

• SDPD should continue to conduct quarterly performance

evaluations for its licensed towing and impound

contractors and submit these forms to the Purchasing and

Contracting Department for monitoring.

City Management agreed with 3 of the 4 recommendations. SDPD

did not agree to compile and report information on alternative

policy options.

For more information, contact Andy Hanau, City Auditor at (619)

533-3165 or CityAuditor@sandiego.gov

December 20, 2022

Honorable Mayor, City Council, and Audit Committee Members

City of San Diego, California

Government Auditing Standards (section 9.68) state that if, after a report is issued,

auditors discover information that affects the findings or conclusions, they should

communicate with appropriate entities and known users to update the report.

After the November 14 publishing of our Performance Audit of the City’s Towing

Program, our office received an inquiry raising an issue regarding the estimated fiscal

impact to the City from lien sales. The party was able to provide additional evidence

substantiating their position, and we confirmed the information with SDPD before

updating and re-issuing our report. Although we have revised the data, the report’s

overall findings and recommendations remain. In fact, we believe this matter

underscores our stated point and recommendations about the importance of more

periodic and transparent program monitoring in compliance with existing Council Policy.

The high-level takeaway from the change is the estimated amounts for the fiscal loss to

the City in the event of lien sales of impounded vehicles decreases from approximately

$808,000 per year to $309,000 per year. The amount that impound providers lose is

correspondingly higher. The impacts to vehicle owners are the same as previously

reported.

Specifically, the City’s uncollected costs in the event of a lien sale include the Tow

Impound Cost Recovery Fee, but do not include the towing and dispatch fees. This new

information affects calculated figures within Exhibits 11, 12, and 13 of the report. For

Exhibit 11, our estimated towing program deficit for FY2023 changes from

approximately $2 million to $1.5 million. In Exhibits 12 and 13, our overall titles and

takeaways stay the same. However, the amounts owed to/lost by the City in the event of

a given lien sale decrease from $150 to $63.

We make diligent efforts to ensure information we publish is as accurate as possible

before a report is made public, including sharing draft versions with relevant City

departments, and meeting to discuss potential discrepancies, inaccuracies, and other

issues. The information regarding this issue that was initially included in the report was

based on statements and data provided and reviewed by SDPD. After we made the

revisions, we confirmed the revised information with SDPD before re-issuing our report.

OFFICE OF THE CITY AUDITOR

600 B STREET, SUITE 1350 ● SAN DIEGO, CA 92101

PHONE (619) 533-3165 ● CityAuditor@sandiego.gov

TO REPORT FRAUD, WASTE, OR ABUSE, CALL OUR FRAUD HOTLINE: (866) 809-3500

Although this issue did not come to light until after publishing, we take seriously our

duty to provide the most accurate and complete information we are aware of in the

interests of the public and in conformance with Government Auditing Standards.

Respectfully submitted,

Andy Hanau

City Auditor

cc: Eric K. Dargan, Chief Operating Officer

David Nisleit, Chief of Police, San Diego Police Department

Honorable City Attorney, Mara Elliot

Matt Vespi, Chief Financial Officer

Jessica Lawrence, Director of Policy, Office of the Mayor

Christiana Gauger, Chief Compliance Officer

Charles Modica, Independent Budget Analyst

November 14, 2022 (updated version issued December 20, 2022)

Honorable Mayor, City Council, and Audit Committee Members

City of San Diego, California

Transmitted herewith is a performance audit report of the City’s towing program. This report

was conducted in accordance with the City Auditor’s Fiscal Year 2022 Audit Work Plan, and the

report is presented in accordance with City Charter Section 39.2. Audit Objectives, Scope, and

Methodology are presented in Appendix B. Management’s responses to our audit

recommendations are presented starting on page 46 of this report. Per Government Auditing

Standards Section 9.52, our response to Management’s comments is on page 50.

We would like to thank staff from the San Diego Police Department for their assistance and

cooperation during this audit. All of their valuable time and efforts spent on providing us

information is greatly appreciated. The audit staff members responsible for this audit report

are Niki Kalmus, Megan Jaffery, Nathan Otto, and Matthew Helm.

Respectfully submitted,

Andy Hanau

City Auditor

cc: Eric K. Dargan, Chief Operating Officer

David Nisleit, Chief of Police, San Diego Police Department

Honorable City Attorney, Mara Elliot

Matt Vespi, Chief Financial Officer

Jessica Lawrence, Director of Policy, Office of the Mayor

Christiana Gauger, Chief Compliance Officer

Charles Modica, Independent Budget Analyst

OFFICE OF THE CITY AUDITOR

600 B STREET, SUITE 1350 ● SAN DIEGO, CA 92101

PHONE (619) 533-3165 ● CityAuditor@sandiego.gov

TO REPORT FRAUD, WASTE, OR ABUSE, CALL OUR FRAUD HOTLINE (866) 809-3500

Table of Contents

Background ................................................................................................................ 1

Audit Results .............................................................................................................. 7

Finding 1: The City should strengthen the public oversight and

transparency of the vehicle towing program by publicly reporting on the

program’s outcomes, impacts to residents, and potential revisions to tow

policies and practices. ...................................................................................... 7

Recommendations 1–3 ............................................................................... 32

Finding 2: Internal oversight of the towing program is strong and SDPD

should continue to conduct performance evaluations in compliance with

the City’s contract guide. ................................................................................ 36

Recommendation 4 ..................................................................................... 39

Appendix A: Definition of Audit Recommendation Priorities ............................ 40

Appendix B: Objectives, Scope, and Methodology ............................................... 41

Appendix C: The City of San Diego’s Towing Rates and Fees as of FY2022 ........ 45

Management Response……………………………………………………………………….……… 46

City Auditor’s Comments to the Management Response…………………………….. 50

Performance Audit of the City’s Towing Program

OCA-23-005 Page 1

Background

Towing is intended to

provide public benefits

but can also

disproportionately

impact certain

populations.

All San Diegans benefit from services that reflect the needs of

residents and communities. Towing is a public service that

benefits communities by ensuring public safety and that parking

availability is equitable. Towing provides public benefits, such as

ensuring the streets are clear for street sweeping, parking is

available for all, parking rules and laws are followed, and

vehicles are registered.

California State law gives cities the ability to tow vehicles and

permits them to adopt additional laws and policies regulating

the towing of vehicles in their own jurisdiction. Consequently, a

local government’s policies may impact how various types of

infractions are enforced. Therefore, the City of San Diego (City)

can make policy decisions to alter its towing practices within its

jurisdiction. In San Diego, the City can tow for obstructing flow of

traffic or causing a hazard, preventing access to a fire hydrant,

and for parking on City streets for over 72 hours, among several

other reasons.

Towing can also have disproportionate impacts on vulnerable

populations, such as people who are low-income or are

experiencing homelessness. Some towing reasons that

disproportionately affect low-income people and people who are

experiencing homelessness are often associated with higher

towing and impound fees and are more likely to result in a lien

sale.

1

For some people, a vehicle tow may result in the

permanent loss of their vehicle, loss of employment, loss of

access to education and medical care, and other consequences.

In fact, this audit was prompted by Councilmembers’ concerns

over the towing program’s impact on low-income San Diegans.

1

As discussed in Finding 1, Disproportionate Impact Tows—five or more unpaid parking citations, expired

registration over six months, and 72-hour parking violations—disproportionately affect low-income people and

persons experiencing homelessness.

Performance Audit of the City’s Towing Program

OCA-23-005 Page 2

SDPD administers the

City’s towing program.

The San Diego Police Department (SDPD) authorizes the towing

of approximately 20,000 vehicles each year from public streets

and highways. SDPD’s Tow Administration Unit is a specialized

unit that manages the City’s towing program for City-initiated

tows—tows ordered by a sworn police officer or City entity on

public streets and highways.

2

Unlike many other cities, the Tow

Administration Unit is a dedicated unit with an administrative

sergeant who oversees the towing program’s operations

including towing, impound, storage, release, disposal, and billing

for City-initiated tows.

The City is not responsible for towing from

a privately-owned parking lot unless there is a violation of the

law. In addition, according to SDPD, any tow that could be

considered predatory, such as a tow company proactively towing

a vehicle in violation of the law without a request from SDPD, is

investigated in the same way as any other crime.

The organization of the towing program allows the City to

provide program transparency and have control over the

program’s billing and costs. The towing program seeks full cost

recovery, collection of accurate towing data, accurate billing, and

to protect citizens from being taken advantage of by towing and

impound providers.

The City contracts with

third-party vendors to

provide towing services.

The City contracts with licensed towing and impound providers

to perform towing services, impounds, releases, storage

services, and vehicle disposal services. In fiscal year (FY) 2017,

the City contracted with eight companies for towing services and

four companies for impound services using one-year contracts

with four one-year extensions. According to the Chief Operating

Officer, due to City Council’s request for this audit, the contracts

were extended for an additional year in FY2023.

The City also contracts with AutoReturn, a towing dispatch

provider, to provide dispatch, billing, and data management

services. AutoReturn randomly selects and dispatches the

closest towing provider to perform a tow based upon the

location of the incident. AutoReturn also monitors the type and

size of the tow, equipment necessary versus what was used,

2

According to SDPD, tows ordered by SDPD at the scene of an accident are considered private tows. Private

property owners will call a towing provider to initiate tows on private property.

Performance Audit of the City’s Towing Program

OCA-23-005 Page 3

mileage, response times, vehicle information, towing reasons,

and any other pertinent information.

The City’s towing

contractors work with

SDPD to tow and

impound vehicles.

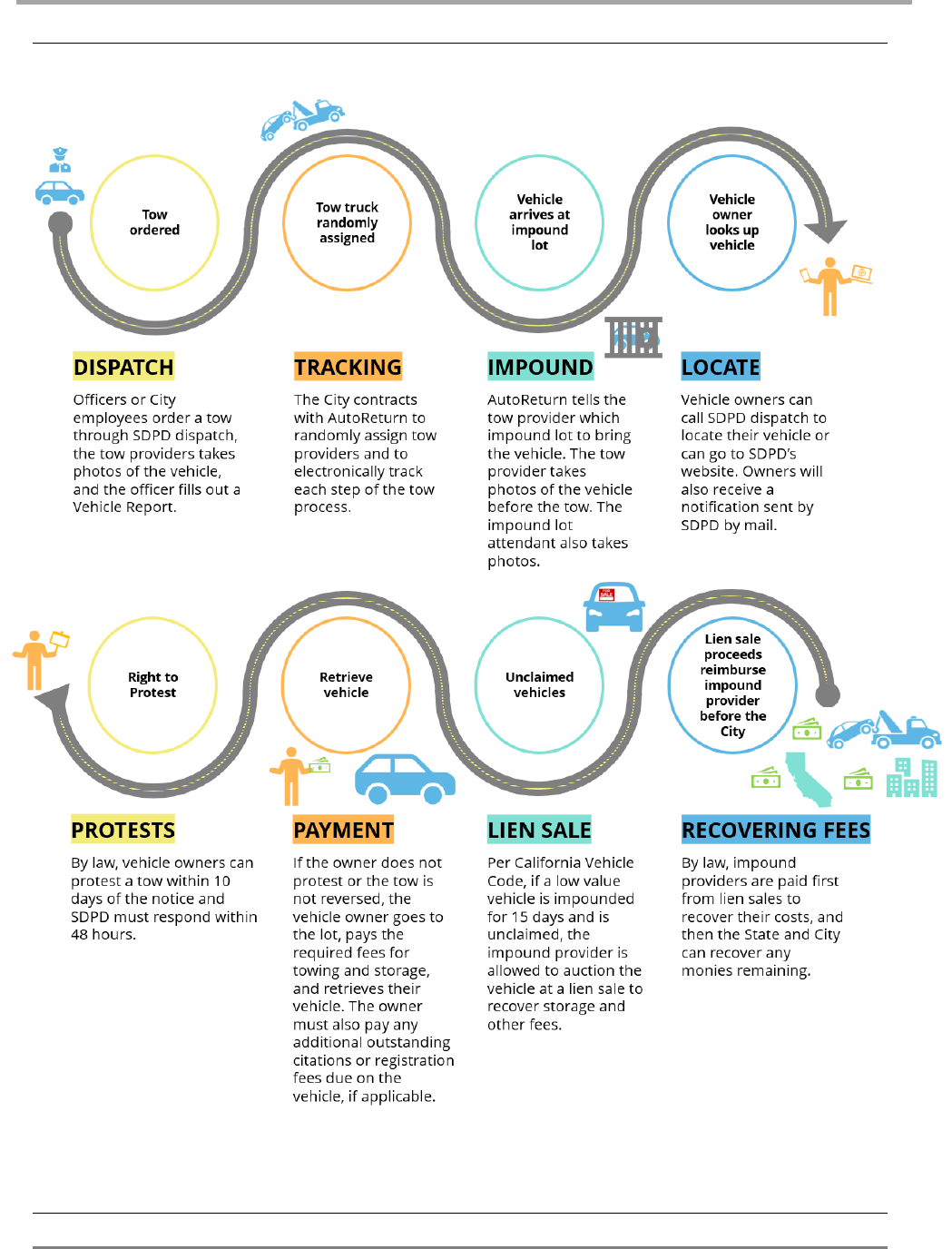

Exhibit 1 provides a high-level overview of the towing process.

When an officer or City employee orders a tow, a towing

provider tows the vehicle to the nearest impound lot (as directed

by AutoReturn). If a vehicle owner suspects their vehicle has

been towed, they can call AutoReturn or SDPD, or they can visit

SDPD’s website and search for their vehicle. According to SDPD,

within 48 hours of any vehicle being impounded by SDPD, the

Records Unit mails a notice to the registered vehicle owner

informing them of the impound and of their right to a tow

hearing, which must be requested within 10 days of the notice.

Vehicle owners must pay all applicable fees for the vehicle to be

released.

If a vehicle owner cannot pay or does not retrieve their vehicle,

the impound provider can auction the vehicle at a lien sale. The

impound provider is required by law to send the registered

owner lien notices and to request a lien sale from the California

Department of Motor Vehicles. Upon sale of the vehicle,

California law allows the impound provider to use the profit to

reimburse itself first for outstanding storage fees, and then if the

proceeds of the sale are greater than the storage expense, the

impound provider is required to satisfy debts to the legal owner,

the holder(s) of any liens, or written interest in the vehicle. Then,

once all other interests are addressed, the funds will go to the

State, and finally to the City for any fees accrued.

3

3

Discussed in detail in Finding 1, lien sales often do not make enough profit to reimburse the Licensed

Impound Provider for their storage services. Average lien sale price garners 45 percent of the total amount of

fees owed (storage, tow, and the City’s cost-recovery fee).

Performance Audit of the City’s Towing Program

OCA-23-005 Page 4

Exhibit 1

The City of San Diego’s Towing Process

Source: Auditor generated based on review of SDPD’s towing manual and relevant sections of the

California Vehicle Codes.

Performance Audit of the City’s Towing Program

OCA-23-005 Page 5

The towing program’s

fees and rates must be

approved by City

Council and/or City

Management.

The cost of the towing program is divided between the towed

vehicle’s registered owner and the contracted impound

providers. The City establishes and sets the towing and storage

rates paid by vehicle owners. The applicable rates are stated

within the towing contracts and SDPD’s towing program manual.

According to contract documents, the rates are based on

estimates of aggregate impound provider costs and fees.

Appendix C details the City’s towing rates and fees, who sets the

amount, and who receives each payment.

When a vehicle is not sold in a lien sale, the vehicle owner pays

the impound provider the City’s tow impound cost-recovery fee

(cost-recovery fee), storage fees, and a towing rate (i.e., cost of

the tow). The impound provider recovers its storage expenses

through the fees it charges the vehicle owner upon the vehicle’s

release. The impound provider then pays the City a franchise fee

for each vehicle impounded, and the City pays the towing

provider and AutoReturn their contracted rates for their

respective services. This structure assures that the towing

provider and impound provider cannot collude or create side

agreements for rerouting vehicles and provides a transparent

financial transaction for the safety of all parties involved. Exhibit

2 illustrates an example of a standard tow stored for one day

overnight and how much money the City, impound provider, tow

provider, and AutoReturn would receive from the vehicle

owner’s payment.

Performance Audit of the City’s Towing Program

OCA-23-005 Page 6

Exhibit 2

The Vehicle Owner Pays to Retrieve Their Vehicle and Payment is Split Among the

City, Impound Provider, Towing Provider, and AutoReturn

Note: The impound provider pays the City the $63 cost-recovery fee, originally paid by the vehicle

owner, and an $83 franchise fee for the privilege of contracting with the City.

Source: Auditor generated based on review of SDPD’s towing manual. Graphic is generated based on

an example of a standard duty vehicle (i.e., light duty or average vehicle) located in an urban zone

and picked up the day after it was towed.

In cases where a vehicle is lien sold, the City may recover its cost-

recovery fee from sale proceeds only if the sale price is greater

than the storage fees accrued, as discussed in Finding 1.

The cost-recovery fee and franchise fee allow the City to recover

all (but not exceed) actual and reasonable towing program

expenses. Under California law, the City cannot capture any

revenue that exceeds its actual program expenses relating to the

removal, impound, storage, or release of an impounded vehicle.

These fees are periodically adjusted via the City’s user fee

update process and must be approved by City Council.

Performance Audit of the City’s Towing Program

OCA-23-005 Page 7

Audit Results

Finding 1: The City should strengthen the public oversight

and transparency of the vehicle towing program by

publicly reporting on the program’s outcomes, impacts to

residents, and potential revisions to tow policies and

practices.

A general program

overview is necessary

for City leadership to

make informed

decisions regarding the

towing program’s

performance.

Several elements are critical to monitoring the towing program’s

performance, such as monitoring performance measures,

assessing outcomes, and informing City leadership of the

program’s outcomes. Per City Council Policy 500-03, the San

Diego Police Department (SDPD) should provide annual updates

regarding the City’s towing program to City Council and the

public; however, SDPD has not provided a comprehensive

update since 2013.

Without fundamental program information and regular updates,

City leadership cannot assess the towing program’s performance

and take informed action to alter the program’s outcomes. We

found that while SDPD monitors and assesses the towing

program’s performance and that of its contractors, it does not

regularly report basic program information and performance

measures to City Council. Therefore, City leadership should be

informed of key performance measures on overall towing

trends, such as:

Program overview including Tow Administration Unit

activities, such as training, inspections conducted, and

operational changes or upgrades;

Volume of tows, including number of tows per reason,

number of vehicles impounded per year, number of

vehicles sold per reason, and number of vehicles

towed/impounded by location per year;

Demand for parking enforcement in the City as

measured by number of Get It Done requests for

parking violations, including 72-hour violations;

Response times for licensed tow providers;

Performance Audit of the City’s Towing Program

OCA-23-005 Page 8

Number of bad tows/post-storage hearing reversals;

4

and

Distribution of time from vehicle impound to release.

SDPD’s 2013 Update to

the Public Safety and

Livable Neighborhoods

Committee included

information on the

towing program’s

performance; however,

additional information

should be provided in

future reports.

SDPD made a good faith effort to meet the spirit of Council

Policy 500-03 (CP 500-03) with its last comprehensive update to

the City Council

5

in 2013, even though CP 500-03 lacks specific

requirements for certain critical information to be included in

the updates.

6

The 2013 update included a high-level overview of

the Tow Administration Unit’s operations and training activities;

towing program data, such as tow provider response times and

number of vehicles towed by towing reason; and operational

upgrades, such as AutoReturn’s provision of smartphones to

licensed towing providers to improve response times.

The 2013 update from SDPD showed a multi-year trend of the

declining number of tows per year. More importantly, the report

gave context to this trend. It stated that the decline was due to

changes in operational policy that allowed greater discretion

among officers to decide whether to tow a vehicle, as well as a

decrease in the number of sworn officers, which reduced

proactive patrol that generates tows. This kind of context is

particularly relevant and should be relayed to City Council given

SDPD’s policy of reduced enforcement during COVID-19, as

discussed later in this finding. While the 2013 report included a

good amount of general information on the towing program, we

found that the report lacked more detailed information

contextualizing the towing program’s effects on residents and

the City, discussed in the following sections.

4

Post-storage hearing reversals occur when the City reimburses or waives a vehicle owner’s towing fees as a

result of a “bad tow,” (i.e., an error made by an officer and/or tow provider in which the vehicle was legally

parked and/or should not have been towed).

5

Council Policy 500-03 specifically requires that SDPD report to the Public Safety and Livable Neighborhoods

Committee (PSLN). However, for general use, we refer to the City Council throughout this report in lieu of PSLN

because the committee is ultimately an arm of the City Council.

6

https://docs.sandiego.gov/reportstocouncil/2013/13-015.pdf

Performance Audit of the City’s Towing Program

OCA-23-005 Page 9

Council Policy does not

specify that high-level

towing program trends

and performance—

including demand for

towing in the City, time

a vehicle is impounded,

and the geographical

distribution of tows—

should be included in

the annual updates.

Since Council Policy 500-03 does not provide direction on what

should be presented, SDPD is not required to present specific

towing trends or program information. However, we found

several important trends and takeaways from recent towing

practices that highlight towing program changes and potential

effects to the City and residents. From FY2017 to FY2021, as

shown in Exhibit 3 below, towing has declined by 39 percent in

the City of San Diego. Some recent reasons for this include

discretion among officers when deciding to tow a vehicle and

reduced enforcement during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Exhibit 3

The Volume of City-Initiated Tows per Fiscal Year Has Been Decreasing

Note: Private tows and tows/transfers of City vehicles are excluded. Data reflects July 1, 2016 to June

30, 2021.

Source: Auditor generated based on towing data provided by SDPD.

While the number of tows has been decreasing, the number of

parking complaints has been increasing on the City’s Get It Done

platform.

7

Parking complaints demonstrate the demand for

parking in the City and highlight how SDPD must balance the

public’s desire for enforcement with the consideration of

disproportionate impacts to vulnerable populations. Exhibit 4

demonstrates trends in the demand for all parking enforcement

7

Get It Done is the City’s platform that can be used to report problems related to City assets via a mobile

application or through the Get It Done website.

28,216

23,367

20,147

16,897

17,169

2017 2018 2019 2020 2021

NUMBER OF TOWS

FISCAL YEAR

Performance Audit of the City’s Towing Program

OCA-23-005 Page 10

in San Diego as measured by Get It Done requests from the

public, including 72-hour parking violations, abandoned vehicles,

and parking zone violations. In 2017, after Get It Done first came

online, about 30,000 requests for parking enforcement were

received. This increased to more than 60,000 in 2019. A

significant drop in requests occurred in 2020, likely due to the

COVID-19 pandemic, and requests rebounded to more than

50,000 in 2021. SDPD expects the number of requests likely to

remain above 50,000 as received in 2021.

Exhibit 4

Parking Requests from Get It Done Demonstrate the Demand for Parking

Enforcement

Note: Data includes any requests submitted through Get It Done, and includes 72-hour violations,

abandoned vehicles, and parking zone violations.

Source: Auditor generated based on Get It Done data from the City’s Open Data Portal, filtered to

parking requests.

Furthermore, reporting on the number of post-storage hearing

reversals per year would also help City leadership assess

potential patterns of improper tows and evaluate SDPD’s

performance. Between FY2017 and FY2022, SDPD reversed 316

tows out of 119,059 total tows, or approximately 1 in 357 tows.

This, in part with additional controls discussed in Finding 2,

indicates strong controls over the towing program.

28,557

39,410

61,384

35,737

54,622

2017 2018 2019 2020 2021

NUMBER OF REQUESTS

CALENDAR YEAR

Performance Audit of the City’s Towing Program

OCA-23-005 Page 11

Over half of impounded

vehicles in the City are

released in less than 24

hours of impound.

Information on the amount of time a vehicle is stored in City

impound lots before release can help policymakers determine

the relationship between the time in storage and fees accrued.

Exhibit 5 shows that most vehicles are released from impound

in less than 24 hours. Data also shows that one-fourth of

vehicles released in San Diego are retrieved within 4 hours of

impound.

Exhibit 5

Vehicles Released Were Most Commonly Retrieved from Impound Lots in Less Than

24 Hours

Note: Only vehicles towed, impounded, and then released from impound are included. Data reflects

July 1, 2016 to March 20, 2022.

Source: Auditor generated based on towing data provided by SDPD.

SDPD should report to

City Council on the top

towing reasons,

number of vehicles

sold, and geographic

distribution of tows to

assess the program's

impacts on residents.

City leadership can use the number of vehicles sold per tow

reason to estimate the likelihood that a tow will result in a

greater number of vehicles sold in lien sales. For example,

Exhibit 6 shows that the top two towing reasons for FY2017 to

FY2022—expired registration and 72-hour parking violations—

were more likely to result in a lien sale. Specifically, for expired

registration tows, 47 percent were eventually sold, and for 72-

hour parking violations, 57 percent were eventually sold.

Performance Audit of the City’s Towing Program

OCA-23-005 Page 12

Exhibit 6

The Top Two Towing Reasons—Expired Registration and 72-hour Parking Violations—

Were More Likely to Result in a Lien Sale Than Most Other Types of Tows (FY2017–

FY2022)

Note: According to SDPD, in 2021 there were approximately 1.4 million registered vehicles in the City

of San Diego.

Source: Auditor generated using towing program data provided by SDPD. Data reflects July 1, 2016

to March 20, 2022.

Finally, the number of tows per year by location would provide

City leadership with general geographic knowledge of the towing

program’s outcomes. For example, Exhibit 7 shows that most

tows occurred in Council Districts 2 and 3 between FY2017 and

FY2022. We also found that the top towing reason in Districts 2

and 3 combined were for violations of special event signs, which

made up 30 percent or approximately 12,500 of the tows in

those districts. Districts 2 and 3 comprise downtown San Diego

and several beach areas, which may correlate to the high

number of special event tows. This information provides

additional context for City leadership to understand the

geographical distribution of tows and their reasons. SDPD could

0 5,000 10,000 15,000 20,000 25,000 30,000

Displaying real registration related decal belonging to other vehicle

5 or more parking citations

Blocking a private driveway

Recovered stolen vehicle

Driver required by law to be arrested and taken into custody

Violation of special event posted signs 24 hours before

Traffic accident - no injury

Vehicle parked on street preventing cleaning / repair to street

Driving without a valid driving license

Violation of special event with permament signs

72 hour parking on public property

Registration expired over 6 months

Sold Not Sold

Performance Audit of the City’s Towing Program

OCA-23-005 Page 13

work with the City’s Geographic Information System (GIS) team

to geolocate the towing points and provide a map to City

leadership.

8

Exhibit 7

Most Tows Occurred in District 2 and District 3 Between FY2017 and FY2022

Note: Only towing points with data able to be geolocated are included. Private tows and City

maintenance and transfers between impound lots are excluded. Data reflects July 1, 2016 to March

20, 2022.

Source: EGIS geospatial analysis of geolocated towing events.

8

We worked with the City’s GIS team to analyze geographical tow data. See the Objectives, Scope, and

Methodology section of this report for more detail.

Performance Audit of the City’s Towing Program

OCA-23-005 Page 14

Certain tows have

disproportionate

impacts on vulnerable

residents and should be

presented to City

leadership.

While towing is a public service, some towing reasons can also

disproportionately affect people who are low-income or who are

experiencing homelessness. Research shows the following

towing reasons, which we refer to as Disproportionate Impact

Tows, are often associated with higher towing and impound fees

and are more likely to result in a lien sale.

9

Specifically, they are

tows for:

Five or more unpaid parking citations;

Expired registration over six months; and

72-hour parking violations.

In addition to providing general information on the towing

program and overall trends, SDPD should inform City leadership

on how the towing program disproportionately affects

vulnerable residents. City leadership can use this information to

make informed decisions to balance the program’s competing

goals of enforcement and fairness. Information that appears

highly relevant to Council concerns, and which SDPD should

strongly consider presenting, includes:

Number and percentage of Disproportionate Impact

Tows;

Number and percentage of Disproportionate Impact

Tows resulting in a lien sale; and

Percentage of Disproportionate Impact Tows by

Council District.

Two of the three

Disproportionate

Impact Tows are by far

the most common

towing reasons in the

City.

The City’s top two towing reasons—expired registration over six

months and 72-hour parking violations—are also types of

Disproportionate Impact Tows. Knowing the volume of

Disproportionate Impact Tows in the City allows policymakers to

assess the extent to which towing adversely affects low-income

residents. It also allows policymakers to assess the proportion of

9

The 2019 study, Towed into Debt, is an in-depth collaborative analysis examining towing practices throughout

the State of California. The study examines towing practices in the context of local jurisdictions within the State,

and details the significant and disproportionate effects that several towing reasons in particular—five or more

unpaid parking citations, expired registration over six months, and 72-hour parking violations—can have on

people who are low-income or experiencing homelessness. Available at: https://wclp.org/wp-

content/uploads/2019/03/TowedIntoDebt.Report.pdf

Performance Audit of the City’s Towing Program

OCA-23-005 Page 15

Disproportionate Impact Tows relative to other tows in the City.

For example, Exhibit 8 shows that the number of

Disproportionate Impact Tows has remained relatively steady,

even as the overall number of tows has declined in the City since

FY2017.

Exhibit 8

The Number of Disproportionate Impact Tows Has Remained Relatively Steady Since

FY2018 Even as the Number of Overall Tows Has Decreased

Note: Disproportionate Impact Tows are tows for five or more unpaid citations, expired registration

over six months, and 72-hour parking violations. Private tows and tows of City vehicles for

maintenance or transfer between impound lots are excluded from the Other Tows category. Data

reflects July 1, 2016 to March 20, 2022.

Source: Auditor generated based on towing data provided by SDPD.

27%

35%

38%

40%

37%

0

5,000

10,000

15,000

20,000

25,000

30,000

2017 2018 2019 2020 2021

NUMBER OF TOWS

Disproportionate Impact Tows Other Tows

Performance Audit of the City’s Towing Program

OCA-23-005 Page 16

Disproportionate

Impact Tows are much

more likely to result in

a lien sale.

While only 12 percent of non-Disproportionate Impact Tows

result in a lien sale, Disproportionate Impact Tows are

approximately 3–5 times more likely to result in a lien sale, as

shown in Exhibit 9.

10

Exhibit 9

Disproportionate Impact Tows Were About 3 to 5 Times More Likely to Result in Lien

Sales Than All Other Tows

Note: Disproportionate Impact Tows are tows for five or more unpaid citations, expired registration

over six months, and 72-hour parking violations. Private tows and tows of City vehicles for

maintenance or transfer between impound lots are excluded. Data reflects July 1, 2016 to March 20,

2022.

Source: Auditor generated based on towing data provided by SDPD.

The percentage of

Disproportionate

Impact Tows varies by

Council District.

Reporting on the percentage of Disproportionate Impact Tows

by Council District can serve as a useful monitoring tool for

decisionmakers on how tow policies and practices impact

various communities across the City. For example, we found

that, for the past five years, Districts 4 and 8 had a substantially

higher percentage of Disproportionate Impact Tows than the

10

By law, impound providers are paid first from lien sales to recover their costs, and then the State and City can

recover any fees remaining.

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100%

72 hour parking on public property

Registration expired over 6 months

5 or more parking citations

All Other Tows

Sold Not Sold

Performance Audit of the City’s Towing Program

OCA-23-005 Page 17

Citywide average of 29 percent, as shown in Exhibit 10. These

Council Districts also correspond with two of the three lowest

median household incomes per Council District. In 2020, District

8 had the second lowest median household income of just over

$50,000, while District 4 had the third lowest of approximately

$57,000. Comparatively, District 6 had a median household

income of about $75,000 and District 5 had a median household

income of $105,000.

Exhibit 10

Districts 4 and 8 Had a Substantially Higher Percentage of Disproportionate Impact

Tows Than the Citywide Average (FY2017–FY2021)

Note: Disproportionate Impact Tows are tows for five or more unpaid citations, unpaid registration

over six months, and 72-hour parking violations. Private tows and tows of City vehicles for

maintenance or transfer between impound lots are excluded. Data reflects July 1, 2016 to March 20,

2022.

Source: Auditor generated based on towing data provided by SDPD and geospatial analysis

conducted by the City’s EGIS team.

15%

23%

28%

28%

30%

32%

33%

39%

45%

Citywide Average, 29%

District 3

District 5

District 1

District 2

District 7

District 9

District 6

District 4

District 8

Performance Audit of the City’s Towing Program

OCA-23-005 Page 18

City policymakers

should be informed of

the towing program’s

fiscal impacts on the

City and its residents.

SDPD has not made required reports to the City Council on the

program in almost a decade. At the City’s FY2022 user fee

meeting, City Council expressed concern over the program’s

fiscal impacts, as well as the impacts the towing program has on

low-income people. As a result, City Council decided to postpone

approval of the program’s fee increases until it received more

information on program operations. According to figures

provided by SDPD, this has resulted in a program subsidization

of approximately $1 million in foregone administrative revenue

for FY2023.

11

Had the City Council known more about the

program’s operations, it may have approved the proposed fee

increases and/or considered other policy changes, such as

implementing reduced or waived fees for low-income vehicle

owners.

SDPD should capture

total program costs and

inform City leadership

of the true cost of

subsidizing the towing

program.

SDPD presents user fees for the towing program with an

intended cost recovery target. However, these fees appear to

only capture personnel, labor, and some administrative costs for

the personnel who administer the program. We found that SDPD

does not appear to capture the towing program’s full costs—for

example, by including additional lost revenues after a vehicle is

lien sold. SDPD has neither historically reported nor calculated

this information and did not present it in its 2013 update to City

Council.

SDPD should present the total costs of the towing program so

policymakers can make informed policy decisions. When SDPD

presents the towing program’s cost information at the City’s user

fee meeting, it only presents the anticipated expenses that its

administrative fees—cost-recovery fee and franchise fee—are

intended to recover. These program costs cover the

administrative expenses and labor of the Towing Administration

Unit employees and other SDPD personnel who administer the

program, as well as some lost revenue due to lien sales. While

the user fee update noted a small General Fund subsidy of

approximately $7,285, this amount does not capture the true

subsidy of the program. Furthermore, the anticipated program

costs presented do not account for other program costs that

11

The subsidized amount is the difference between SDPD’s projected revenue based on its proposed

administrative fees and estimated tows and the current administrative fees.

Performance Audit of the City’s Towing Program

OCA-23-005 Page 19

affect the program’s cost recovery—such as additional lost

revenues due to lien sales.

The City subsidizes the

towing program’s costs.

We found that the City subsidizes the towing program by

approximately $1.5 million, as shown in Exhibit 11. Because

SDPD only accounts for its labor costs associated with the

program, it does not account for the other factors that underlie

the true deficit. These factors include other unaccounted

program costs, such as lost revenue from cost recovery fees due

to lien sales and waived fees for bad tows.

Performance Audit of the City’s Towing Program

OCA-23-005 Page 20

Exhibit 11

Estimated Towing Program Deficit for City-Initiated Tows for FY2023 is $1.5 Million

Program Costs

City User Fee Costs

1

$ 4,055,446

Tow Fees Paid to Towing Providers

2

$ 1,375,335

Dispatch Fees Paid to Dispatch Provider

3

$ 465,498

Total Program Expenses

$ 5,896,279

Program Revenues

Cost-Recovery Fees

4

$ 2,631,298

Tow Fees

5

$ 1,375,335

Dispatch Provider Fees

6

$ 465,498

Total Program Revenues

$ 4,472,131

Program Loss

Total Loss for Below-Cost Fees

$ 1,115,148

Total Loss for Lien Sales

$ 309,000

Waivers

7

$ 46,100

Total Loss

$ 1,470,248

Notes:

1

Includes SDPD’s estimated personnel, administrative, and labor costs associated with program

operations for FY2023.

2

Tow rates are pass-through fees that the City collects from its contracted impound providers and

passes on to its contracted towing providers. Tow rates paid to the City’s towing providers vary

based on the type of vehicle towed (standard, medium, heavy) and the zone from where they are

towed—suburban or urban. This cost is based on the rate paid to the towing provider for a standard

duty vehicle towed from an urban zone. Thus, the cost here could be higher due to the variance in

fees based on the types of tows and zones where the tows occurred, and any costs incurred during

the tow.

3

The City’s dispatch fee ($22) is a pass-through fee that the City collects from its contracted impound

providers to pay its dispatch provider, AutoReturn, for every tow. The fee is reduced from the City’s

payment to the contracted towing provider.

4

SDPD’s anticipated revenue minus the $309,000 average amount lost in cost-recovery and

franchise fees from FY2017–FY2021.

5

Tow rates are pass-through fees that the City collects from its contracted impound providers and

passes on to its contracted towing providers. See note 2 for the explanation of why tow rates vary.

6

The City’s dispatch fee ($22) is a pass-through fee that the City collects from its contracted impound

providers to pay its dispatch provider, AutoReturn, for every tow.

7

Average amount the City waived in administrative fees from FY2017–FY2021.

Source: Auditor generated based on the towing program’s financial information from SDPD and

AutoReturn.

Performance Audit of the City’s Towing Program

OCA-23-005 Page 21

The towing program’s administrative fees fall far short of

covering the towing program’s anticipated labor costs. In FY2023,

the City will lose approximately $1.15 million due to the

difference between anticipated revenue and expected labor

costs (assuming that all fees are paid in full). This will only

recover approximately 73 percent of the towing program’s labor

costs. However, given that the City has lost an average of

$309,000 in unrecovered cost recovery fees from FY2017–FY2021

due to lien sales, the actual recovery rate is closer to

approximately 65 percent.

The decline in tows and increased personnel expenses also

affect the towing program’s level of cost recovery and subsidy

because the estimated costs and revenues are predicated on

estimated tow volume for the next fiscal year. Between FY2017

and FY2022, the number of tows in the City declined by 39

percent. However, program expenses have increased by 19

percent between FY2019 and FY2023 due to increased salary

and pension expenses for SDPD personnel. During this same

period, the cost recovery and franchise fees were increased

once, in FY2019, by 17 percent and 12 percent,

respectively. These factors, coupled with City Council’s decline of

SDPD’s proposed fee increases in FY2023, keep the program

operating below cost recovery.

Lien sales are costly to

multiple parties.

The City also loses money due to lien sales. With approximately

27 percent of all tows resulting in a lien sale from FY2017–

FY2021, the City stands to lose an average of approximately

$309,000 in FY2023.

12

This loss includes the cost-recovery fees

owed by the vehicle owner that are not recovered when the lien

sale amount falls short of the fees owed.

In fact, as Exhibit 12 shows, no matter how high the accrued

fees are for a vehicle that is sold via lien sale, the City is still out

the amount of its cost-recovery fee, while most of the costs

incurred by the vehicle owner are due to the impound provider.

The total accrued fees include the cost of storage, towing (from

which the tow and dispatch fees due to the City are derived), and

the City’s cost-recovery fee.

12

From FY2017–FY2021, SDPD lost an average of $309,000 in cost-recovery fees.

Performance Audit of the City’s Towing Program

OCA-23-005 Page 22

The situation is particularly worse for the City when lien sales do

not recover an excess amount that is enough to reimburse the

impound provider and the City for outstanding expenses.

13

As

shown in the exhibit, the average amount of accrued fees

(storage, tow, and the City’s cost-recovery fee) for all lien sold

vehicles is $1,174, which garners an average sale price of $526 or

only 45 percent of outstanding costs due from the vehicle

owner. The City’s top two towing reasons—72-hour violations

and unpaid registration tows—which are also Disproportionate

Impact Tows, most frequently result in a lien sale and the

average sale price for these recovers only 25 percent of fees

owed. In these cases, the impound provider recovers less than

half of its outstanding costs and the City will only recover the

franchise, towing, and dispatch fees. The loss to the City may be

even greater in cases where the vehicle owner has outstanding

parking citations that go unpaid.

13

By law, impound providers are paid first from lien sales to recover their costs, and then the State and City can

recover any fees remaining.

Performance Audit of the City’s Towing Program

OCA-23-005 Page 23

Exhibit 12

Average Accrued Fees Exceed Average Lien Sale Prices for All Tows and

Disproportionate Impact Tows; Fees Owed to the Impound Provider Make Up Most of

the Outstanding Costs (FY2017–FY2022)

Notes:

*In this example, the City loses its cost recovery fee, which is usually paid by the vehicle owner to the

City (via the impound provider) upon the vehicle's release or by the impound provider if there is an

excess amount from the lien sale.

**The total accrued fees include storage and lien fees for the impound provider and the City’s costs

directly related to the City’s towing program. The fees do not include outstanding registration fees

and unpaid parking citations that are due to the State and City, respectively. The City's estimated

costs shown here are for a basic tow from an urban zone. When a vehicle is lien sold, the City would

also likely lose out on any other unpaid fees, such as parking citations.

*** The impound provider pays the City fees for dispatch ($22), franchise ($83), and towing (variable)

for each vehicle impounded. Impound providers are required to pay these fees for all vehicles

impounded, regardless of whether they are sold at a lien sale. In instances of private tows, towing

fees are paid by the vehicle owner.

Source: Auditor generated based on data and interviews with AutoReturn, a licensed impound

provider, and SDPD.

Performance Audit of the City’s Towing Program

OCA-23-005 Page 24

Vehicle owners stand to experience the biggest loss when their

vehicle is sold. Not only do they lose their vehicle, but they may

also suffer lost wages or employment, missed medical

appointments, and for some, the loss of housing. Given that the

City’s top two towing reasons—72-hour violations and expired

registration over six months—which are also Disproportionate

Impact Tows, are more likely to result in a lien sale, these towing

types may be particularly harmful to the City’s vulnerable

residents.

A recent federal report states that when faced with a

hypothetical expense of $400, many Americans would pay using

a credit card and carry a balance, and a significant number

would be unable to pay at all. With the average amount of

accrued fees for Disproportionate Impact Tows at almost $2,000,

vehicle owners would be unlikely to afford the expense of

getting their vehicles released. According to an interview with an

impound company, vehicle owners may also be at risk of being

taken to small claims court by the impound provider to recoup

outstanding costs. Additionally, vehicle owners with five or more

unpaid parking tickets may be subject to wage garnishment or

having their tax refunds seized in order to pay for the

outstanding tickets and associated late fees.

Exhibit 13 below provides a simple example of lien sales’ costly

impact to multiple parties. For a vehicle that accrues $1,541 in

fees, the sale price of $526 only garners 34 percent of

outstanding costs. While the impound provider gets the sale

amount, it would still not recover its $952 in remaining

outstanding costs, the City would lose $63, and the vehicle

owner would not only lose their means of transportation but

may suffer additional hardships as mentioned above.

Performance Audit of the City’s Towing Program

OCA-23-005 Page 25

Exhibit 13

Lien Sales May Result in Costly Impacts to Multiple Parties

Note: This is an example based on 30 days of storage. Based on State law requirements, a vehicle

with a value greater than $500 must be stored for at least 30 days before a sale. This means that

impound providers usually incur the expense of 30 days of storage, plus the cost of auctioning the

vehicle before a lien sale.

Source: Auditor generated based on interviews with the City’s dispatch and licensed impound

providers and SDPD, review of SDPD’s towing manual and towing data, and Towed Into Debt.

It is important that SDPD capture all of its program costs to

make day-to-day operational decisions. Furthermore, it is

important that SDPD inform City leadership of the program’s

overall costs. With this information, City leadership can decide

how much of the program it wishes to subsidize to offset costs

to vehicle owners overall, and take actions, such as reducing the

cost-recovery fee, creating a formal subsidy program for

vulnerable people, adjusting enforcement of certain towing

reasons, and/or implementing other program changes.

Performance Audit of the City’s Towing Program

OCA-23-005 Page 26

Waivers for bad tows,

while infrequent, also

affect the towing

program’s level of cost

recovery.

Waivers for bad tows and other circumstances also factor into

the towing program’s level of cost recovery. As discussed later in

this finding, the Tow Administration Unit will waive fees typically

when it is determined that a tow was completed in error.

According to SDPD, the vast amount of the waiver cost stems

from the City paying for towing fees related to impounded

vehicles that belong to victims of crimes; for example, a victim’s

vehicle that is impounded for evidence collection reasons or for

court purposes due to its involvement in a crime. While waivers

are used in less than 1 percent of total tow events each year, the

City waived an average of $46,000 per year from FY2017 to

FY2021.

City leadership should

also know the full cost

of what residents pay

when they get their

vehicle towed.

Considering that towing and impound fees can rapidly accrue on

an impounded vehicle, it is important for City leadership to know

how the towing program’s towing and impound rates impact

residents. SDPD should also present information regarding what

residents pay when their vehicles are towed and impounded, as

well as how the towing program’s rates compare to other

jurisdictions.

We found that SDPD regularly benchmarks its towing rates with

other local jurisdictions. We confirmed the rates with these local

jurisdictions and found that the City of San Diego’s rates are the

lowest among the jurisdictions, as shown in Exhibit 14.

Performance Audit of the City’s Towing Program

OCA-23-005 Page 27

Exhibit 14

SDPD’s Towing and Storage Rates are Lowest Among Other California Jurisdictions

San Diego Chula Vista Oceanside San Jose San Francisco

Towing Rates $178 $235 $245 $250 $268

Storage Rates

$41 per day,

1

st

day $5.50

per hour

$64 per day

$65 outside,

$70 inside per

day

$100 per day*

First 4 hours

free

Light Duty:

24 hours after

first four: $58

Every full

calendar day

after: $69.50

Note: There may be differences in how these jurisdictions charge and assess fees based on how

their towing programs are operationally structured. Figures are provided for the purpose of material

comparison and approximation.

*Vehicle weight not specified in San Jose’s fee schedule.

Source: Auditor generated based on review of light duty towing and storage rates from the cities of

San Diego, Chula Vista, Oceanside, San Jose, and the City and County of San Francisco.

City leadership should

evaluate its options and

articulate a policy

direction on

enforcement and fees

for the towing program

going forward.

The towing program has significant financial, equity, and quality

of life implications for the City and its residents. As such, the City

may want to balance the competing goals of ensuring public

safety, ensuring parking availability is equitable, and mitigating

disproportionate impacts on low-income residents. City

policymakers can consider changes to the towing program

based on alternative models already in place in some California

cities to balance the competing goals of the towing program. We

benchmarked against other California cities’ towing programs to

examine alternative models and subsidy programs, as shown in

Exhibit 15.

15

These models aim to reduce costs and impacts on

vehicle owners.

15

We interviewed the cities of Chula Vista, Oceanside, San Jose, and the City and County of San Francisco.

Performance Audit of the City’s Towing Program

OCA-23-005 Page 28

Exhibit 15

There are Alternative Towing Models that City Policymakers Can Consider to Balance

the City’s Competing Goals

Towing Model/Policy

Benchmark Jurisdictions

that Implemented this Model/Policy

“Text Before Tow”

•

San Francisco

o Residents enroll in program to receive a text

message if their vehicle is subject to a tow

Fee waiver for extenuating

circumstances, often at the

discretion of the program

director/sergeant

• San Diego

• Chula Vista

o Negligent Vehicle Impound fee only*

•

Oceanside

Halted or reduced enforcement

for certain tow reasons

• San Diego

o Halted towing for vehicle habitation during

COVID-19

• San Francisco

o Halted towing for 72-hour violations during

COVID-19

Low Income Payment Plan

• San Diego

o Allows low-income residents to pay down

their outstanding parking citations and to

reduce the burden of accrued charges for late

payments

Subsidy for first time tows, low-

income residents, and persons

experiencing homelessness (PEH)

•

San Francisco**

o Reduced administrative fees for individuals

whose vehicle is towed for the first time and

no administrative fees for individuals who are

low-income or PEH

o Reduced towing fees for individuals who are

low income and a one-time waiver of towing

fees for PEH

Storage fee waiver based on

time of vehicle retrieval

•

San Francisco

o First 4 hours free, 15-day storage waiver for

low-income residents and PEH

“Boot” vehicle before tow

• San Francisco

o Vehicle owners have 72 hours from the time

the boot is affixed to pay the delinquent

citations and penalties and prevent the

vehicle from being towed

• Reduced boot removal fee for low-income

residents and PEH

Performance Audit of the City’s Towing Program

OCA-23-005 Page 29

Charge different rates for

different tow reasons (e.g., more

expensive administrative fee for

criminal offenses)

• Oceanside

o Higher administrative fee applies to criminal

offenses such as speeding contests,

suspended driver's license, etc.

Community Service as

Restitution

•

State of California

o California Penal Code allows a person

convicted of an infraction to elect to perform

community service in lieu of the total fine that

would otherwise be imposed, upon showing

that payment of the total fine would impose a

hardship on the person or their family.

Notes:

* The Negligent Vehicle Impound fee is the cost-recovery administrative fee for the City of Chula

Vista’s tow program. However, the fee is only charged for tow reasons due to the actions of the

driver or owner. For example, the Negligent Vehicle Impound fee is not charged on a stolen vehicle.

The fee can be waived and may include consideration of hardship.

** Some restrictions apply, such as eligibility requirements, including proof of income and/or

presentation of participation in one of the State’s entitlement programs (e.g., Women, Infants, and

Children program or Medi-Cal).

Source: Auditor generated based on benchmarking interviews with the cities of Chula Vista,

Oceanside, San Jose, and the City and County of San Francisco and research.

The City and County of

San Francisco is the

only benchmarked

jurisdiction we found

with a formal towing

subsidy program.

In San Francisco, public discontent over high towing fees

resulted in the development of waivers for first-time tows, low-

income and unhoused residents, and tows for evidence of

crimes or stolen vehicles. The San Francisco Municipal

Transportation Agency (SFMTA) manages the towing program

and conducts more than 40,000 tows per year at a higher cost to

vehicle owners than in San Diego. SFMTA works with its City and

County Treasurer’s Financial Justice Project to determine policy

measures that allow reprieves for those who cannot afford to

pay their fines and fees.

SFMTA’s waiver program includes reduced administrative fees

for first-time tows (i.e., individuals whose vehicle is towed for the

first time) and no fees for individuals who are low-income or

who are experiencing homelessness.

16

For example, repeat tows

16

Some restrictions apply such as eligibility requirements, including proof of income and/or presentation of

participation in one of the State’s entitlement programs (e.g., Women, Infants, and Children program or Medi-

Cal).

Performance Audit of the City’s Towing Program

OCA-23-005 Page 30

are 18 percent more expensive than first time tows. SFMTA also

offers up to 15 days of storage waivers for low-income and

persons experiencing homelessness, the first 4 hours of storage

free for everyone, and a reduced storage fee for the first 24

hours a vehicle is impounded. The City and County of San

Francisco also may “boot” vehicles with five or more delinquent

parking citations. However, the fee to remove the “boot” is

reduced by 85 percent for low-income residents and is waived

one-time for persons experiencing homelessness. In total,

SFMTA subsidizes about $4.5 million in waivers for low-income

and unhoused residents and first-time tows in addition to its $28

million program costs, while program fees and costs continue to

increase.

SFMTA also operates a “Text Before Tow” program that is

provided as a courtesy for residents who sign up for the service.

Users get a text message when their vehicle is in violation and at

risk of being towed for 72-hour parking violations, blocked

driveways, construction zone parking, and temporary no parking

for special events and moving trucks.

City decisionmakers

must also consider the

potential adverse

impacts of alternative

towing models.

When considering policy options, it is important to note the

impacts these models may have in terms of safety, the

environment, and other factors. For example, some of the

benchmarked cities expressed caution with creating subsidy

programs or waivers. SFMTA, for instance, noted that its towing

program’s high costs combined with its waiver and fee reduction

programs contribute to the program’s underfunding. In addition,

the use of booting as an alternative enforcement policy may not

be appropriate for some types of potential towing reasons, such

as 72-hour violations.

17

According to SDPD, the City has not

utilized booting in many years, and if the City were to use

booting, there may be extra costs to the City as well as potential

liability of damaging vehicles.

Halting enforcement of certain towing reasons can have other

impacts. In San Francisco, according to SFMTA, public complaints

increased when it stopped towing for 72-hour parking violations

and abandoned vehicles during the COVID-19 pandemic.

17

According to SDPD, 72-hour violations that are booted may remain on the street and would not mitigate the

concern of a car filling a parking spot for longer than 72 hours.

Performance Audit of the City’s Towing Program

OCA-23-005 Page 31

Similarly, SDPD stated that reduced enforcement of some

parking violations, such as towing for vehicle habitation or 72-

hour violations, can affect public safety. For example, SDPD

stated that reduced enforcement of 72-hour violations, which

are more likely to be abandoned vehicles, increases biohazards,

such as trash and hazardous waste. Finally, when enforcement is

stopped, the lack of an accountability mechanism can result in

more people committing parking violations. For example, one

city we benchmarked against shared that when California

changed legislation to allow a licensed driver to pick up a car

driven by an unlicensed driver instead of towing the vehicle,

officers reported more citations and more experiences with

unlicensed drivers.

Policy decisions

regarding potential

alternative models

should be publicly

presented along with

expected and observed

impacts to residents

and the City.

To evaluate policy impacts and alternative towing program

models, City leadership must be aware of current programs to

assist vehicle owners, and any policy changes with potential or

observed impacts. Therefore, SDPD should report to City Council

on:

The number of waivers given each year, including

reasons; and

The information on policy alternatives from

stakeholders’ input as described in Recommendation

3.

SDPD occasionally

waives towing fees and

has halted enforcement

of certain towing

reasons, but does not

report these

occurrences to City

Council.

Waivers to vehicle owners for towing fees are primarily given for

bad tows following a post-storage hearing; however, SDPD can

also offer a full or partial towing fee waiver to vehicle owners

facing extenuating circumstances at the discretion of the Tow

Administration Unit sergeant. According to SDPD, there have

been approximately five cases in one and a half years in which

citizens have requested reduced fees due to their personal

circumstances. While SDPD tracks waivers in AutoReturn, it does

not formally track when waivers are given in extenuating

circumstances. SDPD also does not report to City leadership or

the public on how, when, and how often these waivers are given.

Should City leadership decide to create a formal subsidy

program, SDPD would require the availability of a subsidized

waiver budget to pay fees for citizens. As such, the number of

waivers for extenuating circumstances given each year and the

Performance Audit of the City’s Towing Program

OCA-23-005 Page 32

reasons for waiving fees should be presented to the public as an

internal control for the use of this subsidy tool.

In April 2020, SDPD halted enforcement of towing for certain

offenses of any vehicles with obvious signs that the vehicle was

being used for habitation. As a result, towing decreased in

FY2020, and according to SDPD, the temporary halt of

enforcement led to people taking advantage of the situation and

accruing numerous parking tickets. This context may help

Councilmembers in their own policymaking, when interacting

with residents of their districts, and in evaluating the towing

program. Thus, SDPD should present information about

enforcement changes as well as any impacts observed to the

community and environment as a result of the policy change.

To address the issues outlined above, we recommend:

Recommendation 1

The San Diego Police Department (SDPD) should present a

report to the Public Safety and Livable Neighborhoods

Committee and/or City Council periodically on the towing

program’s operations. The frequency of the report should be

prior to each of the City’s comprehensive user fee studies

(currently conducted every 3 years), as well as prior to issuing or

renewing a request for proposal for relevant towing and/or

impound contracts. Based on City leadership’s input and City

Council’s approval of the revised Council Policy in

Recommendation 2, SDPD’s periodic report should include all

the following reporting elements and any others that SDPD