1

City of Los Angeles

Alternatives to Traffic Enforcement

Study and Community Task Force

Recommendations

September 2023

Prepared for the Los Angeles Department of Transportation

ITEM 4A

2

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Executive Summary | 3

I. Context and Framing | 12

II. Project Overview | 17

III. Research Findings | 20

IV. Recommendations | 77

V. Appendices | 86

3

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

This report explores options for the City of Los Angeles to pursue “alternative models and

methods that do not rely on armed law enforcement to achieve transportation policy

objectives.”

1

The study is the final deliverable in response to Council Motion CF-20-0875, which

directed the Department of Transportation (LADOT) to manage the production of this document.

This report represents the culmination of over a year’s worth of work undertaken at the behest

of Council and in coordination with the City Working Group, Consultant Team, and Advisory

Task Force. This report provides recommendations for the City Council to consider as it studies

the feasibility of proposed policy changes.. The executive summary includes context and

background for the study, provides an overview of research findings, and summarizes taskforce-

led recommendations.

A. Study Context and Background

This study was initiated in 2020 in the wake of national protests following the murder of

George Floyd. In response to communities’ persistent calls for public safety approaches

that limit the role of police, the Los Angeles City Council passed a motion in October 2020.

The Council Motion (CF-20-0875) directed the Los Angeles Department of Transportation

(LADOT) to oversee this study that evaluates opportunities for unarmed traffic enforcement

in the city.

B. Study Participants

This study included participants from three groups: (1) the City Working Group, (2) the

Consultant Team, and (3) the Traffic Enforcement Alternatives Advisory Task Force. The

role of each is summarized below.

1. City Working Group

The City Working Group includes representatives from City of Los Angeles

departments named in the Council Motion, including the Department of

Transportation (LADOT), Police Department (LAPD), City Administrative Officer

(CAO), City Attorney, and Chief Legislative Analyst (CLA). This working group

informed the project’s parameters, supported LADOT in selecting Advisory Task

Force members, and reviewed deliverables.

2. Consultant Team

The City Working Group selected the consultant team for this study. The team

included the following firms: Estolano Advisors, Equitable Cities, Nelson\Nygaard,

and the Law Office of Julian Gross. The consultant team developed the study in

collaboration with the City’s Traffic Enforcement Alternatives Advisory Task Force.

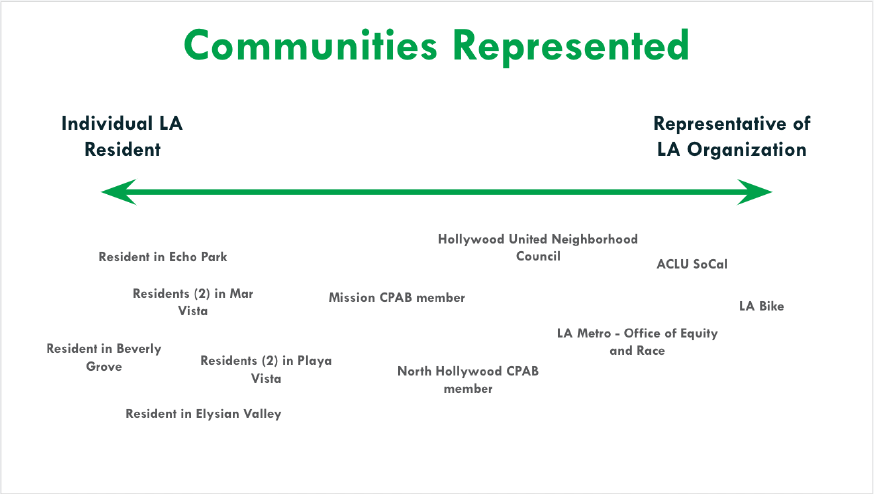

3. Traffic Enforcement Alternatives Advisory Task Force

City Council tasked LADOT with selecting and seating an advisory task force to co-

develop recommendations with the consultant team. The advisory body included 13

members with personal and professional experience related to traffic safety, public

health, mental health, racial equity, academia, and criminal justice. A full list of task

force members is included in Appendix B.

1

Los Angeles City Council (2021). Council File: 20-0875 – Transportation Policy Objectives/Alternative Models and

Methods/Unarmed Law Enforcement. Council Adopted Item. Retrieved March 30, 2023, from

https://cityclerk.lacity.org/lacityclerkconnect/index.cfm?fa=ccfi.viewrecord&cfnumber=20-0875

4

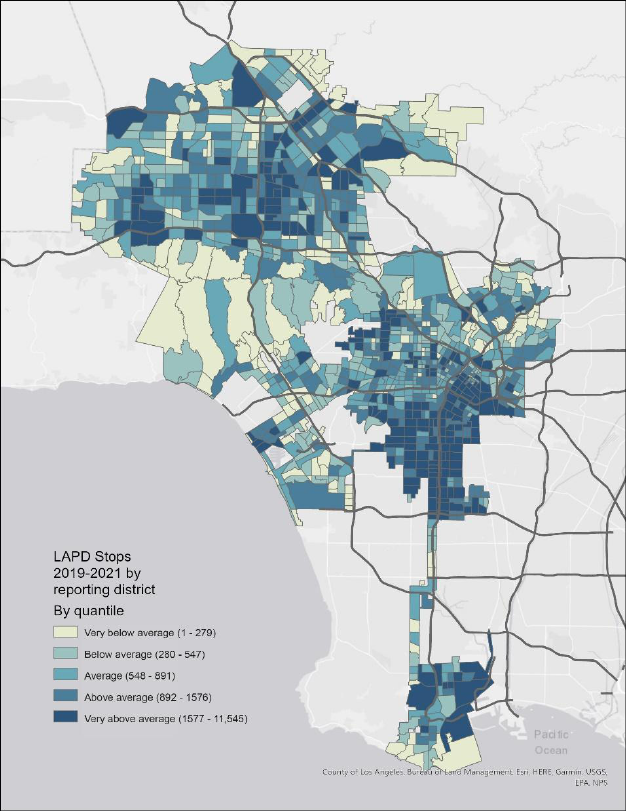

C. Quantitative Research Findings

The quantitative analysis focused on a descriptive analysis of California Racial and

Identity Profiling Act (RIPA) data. RIPA was enacted in 2015 to create a standard

set of data that police departments in California must report publicly. LAPD and

LADOT provided additional data for the quantitative analysis, including information

related to traffic-related collisions, injuries, and deaths. The consultant team

analyzed the last three years of available RIPA data (2019 – 2021) and did a sub-

analysis of data from April – September of 2022 to highlight changes linked to

LAPD’s revised pretextual stop policy. Please see Section IV.B for a detailed

methodology. The key findings are summarized below:

1. LAPD is making fewer stops overall, but traffic stops are

concentrated in certain neighborhoods.

The total number of traffic stops have dropped since 2019. Stops are

concentrated in neighborhoods in and around Hollywood, South Los Angeles,

and Downtown. Most stops are related to traffic violations, with speeding

being the most common infraction. However, stops for speeding only

represent 16% of all traffic violation stops, with slightly more than half of

speeding stops resulting in a driver being issued a citation.

2. Data show disproportionate stops by race.

Considering their share of the city’s population, Black drivers are stopped

more frequently than other racial/ethnic groups. Black travelers are also

subject to more actions (e.g., a police officer drawing a weapon or using force

against an individual) during stops. While police use of force is uncommon

during traffic stops, when these actions do occur, they are used

disproportionately against Black drivers.

3. The revised pretextual stop policy shifted traffic stop

patterns, but disparities persist.

LAPD’s revised pretextual stop policy of March 2022

2

requires officers to

state the reason for initiating a stop. In the six months since the policy change

went into effect, a higher percentage of stops were made for moving

violations compared to the same six-month period in the prior year. The

proportion of Black drivers who were stopped after the policy change declined

from the previous year, but Black drivers continue to be pulled over at higher

rates.

D. Qualitative Research Findings

The qualitative analysis focused on a series of community and practitioner

stakeholder focus groups. These focus groups were augmented by expert

interviews with academics and legal scholars. Please refer to Sections IV.D and

2

Los Angeles Police Department (2022). “Policy – Limitation on Use of Pretextual Stops – Established.” Office of the

Chief of Police. Retrieved from:

<https://lapdonlinestrgeacc.blob.core.usgovcloudapi.net/lapdonlinemedia/2022/03/3_9_22_SO_No._3_Policy_Limitati

on_on_Use_of_Pretextual_Stops_Established.pdf>

5

IV.E for a more detailed methodology and Appendices H-L for interview protocols

and summary presentations.

1. Focus Group Takeaways

While this study was specifically focused on traffic enforcement, many focus

group participants shared their perception of safety to be about more than

just traffic and traffic violence. For example, some expressed a desire for less

enforcement and more human services when discussing traffic safety issues.

Below is a summary of focus group feedback.

a. Traffic stops involve heightened emotions and power

imbalances.

Participants acknowledged that both drivers and police officers have

heightened emotions during stops. Yet, several participants felt that each

stop is rife with power imbalances with officers holding all the power.

b. Speeding and driver aggressiveness is a major concern.

Many participants defined speeding as the top traffic problem in Los

Angeles. Most participants expressed the sentiment that speeding got

worse during the pandemic.

c. Infrastructure improvements are needed.

This project was initially scoped to only speak to traffic enforcement-

related issues. However, in every focus group, the consultant team heard

from participants that they wanted to see the streets engineered

differently and more infrastructure built to combat the issues they were

identifying. Participants identified more protective infrastructure for non-

drivers as a key need.

d. We should bolster active transportation to increase safety.

Many participants opined that they felt unsafe in the city when they were

not in a car. To improve safety, participants suggested more investments

in modes of transportation other than private, single-occupancy vehicles.

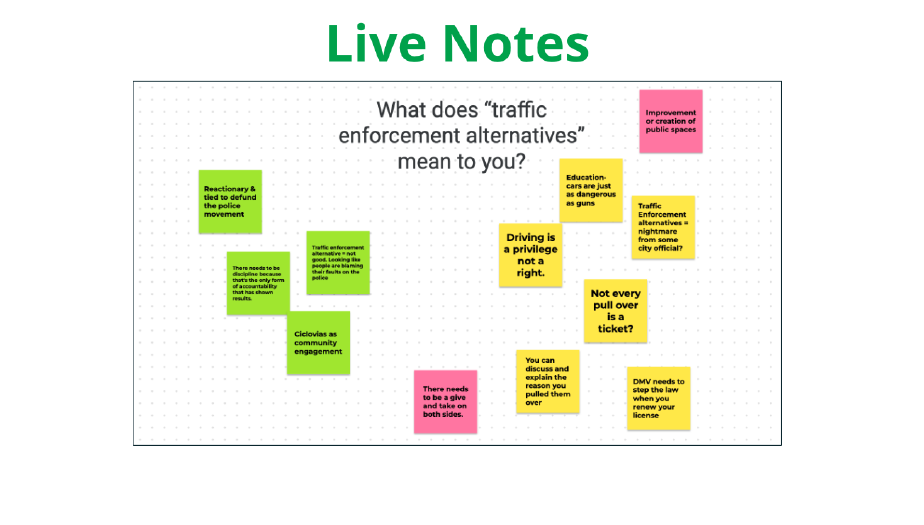

e. There are terminology concerns re: “enforcement

alternatives.”

Not all participants are sure what “enforcement alternatives” mean. In

each focus group, participants asked facilitators to offer more explanation

about the term’s definition. After the facilitators offered more context,

many participants expressed a desire for the City to be clearer messaging

on this topic.

2. Expert Interview Takeaways

In addition to the focus groups, the consultant team conducted a series of

interviews with traffic safety experts. Interviewees had experience working

with jurisdictions attempting to reduce the use of armed police officers

performing traffic enforcement. The key takeaways are summarized below:

6

a. Adopt a comprehensive approach to traffic safety.

Interviewees suggested that traffic safety and Vision Zero frameworks

should consider a holistic understanding of traffic violence. In addition to

promoting physical safety, this approach would also account for the role

that racial discrimination plays in enforcement. It would acknowledge the

stress that people experience related to biased enforcement (e.g., an

individual’s fear of being stopped by police).

b. Shift the focus from enforcement to prevention.

Interviewees emphasized shifting focus from enforcement to prevention.

Prevention could include improving infrastructure or expanding social

programs, and these measures should be treated as an important

component of traffic safety. Rather than rely on increased enforcement,

police can defer to the department of transportation to solve street design

problems and ultimately increase traffic safety.

c. Training has its limits.

Interviewees shared that training alone is an insufficient reform

mechanism for addressing the disparities in traffic enforcement. They

note that years of training reforms have not had the effect of significantly

reducing disparities or meaningfully building community trust. These

trainings fail to critically interrogate the history of traffic stops; instead,

they focus on improving enforcement agencies’ work within the existing

context.

d. Bring employee unions into the conversation early.

Bring unions into conversations about shifting staff responsibilities early in

the process to mitigate potential conflict and promote successful

implementation. Jurisdictions should consider strategies to engage all

affected unions to define how (or if) roles will change, surface key labor

concerns, and work with union leadership to address issues.

3. Legal Considerations

City Council requested that this study include a review of relevant state and

local laws, and interviews with legal experts to assist the consultant team and

the Task Force in developing recommendations. The legal team reviewed the

Los Angeles Municipal Code, the California Vehicle Code, the California

Penal Code and other relevant traffic laws (for a more detailed methodology,

please see Section IV.F). Please note that references to specific code

sections are included in the report’s footnotes. The legal backdrop informs

the scope of recommendations. The legal team focused on the following: (a)

Options to shift enforcement from police, (b) Collective bargaining

considerations, (c) Options to reduce fines, and (d) Laws related to automatic

enforcement.

7

a. Options to Shift Traffic Enforcement Authority Away from

Police Officers

The legal team considered mechanisms that the City of Los Angeles may

consider if it chooses to move to an alternative traffic enforcement model.

Below, is a description of each option:

i. Utilize local employees who are not “peace officers” – for traffic

enforcement generally, or for enforcement of “infractions.”

The City may consider full “civilianization” of traffic enforcement –

i.e., utilizing workers who do not constitute “peace officers” under

state law. Whether the City has discretion to do this broadly under

the Vehicle Code is an open question of state law.

ii. Employ “peace officers” outside of LAPD.

Another option is to utilize employees outside of LAPD, but with

peace officer status to enforce traffic violations. However, only the

employees listed in the penal code as peace officers can have peace

officer status.

iii. Establish a new unarmed unit of LAPD officers.

Third, LAPD could establish a new unit of police officers that

enforces traffic laws but does not carry firearms. State law does not

require any police officers to carry firearms, but rather permits local

agencies to decide if and to what extent they will allow their officers

to carry firearms.

3

b. Public Sector Collective Bargaining

Legal experts and legal research indicated that lengthy, contested

collective bargaining procedures often delay or sideline efforts to revise or

reform law enforcement practices. This issue has affected police reform

efforts to the degree that multiple national advocacy organizations have

established dedicated public websites and databases to track the effects

of police union contracts on reform efforts.

4

Like every public entity in

California, the City of Los Angeles, including both its Department of

Transportation and its Police Department, is subject to state law

regarding collective bargaining negotiations with employees.

5

c. City’s Authority to Reduce Fines for Various Traffic Violations

Some recommendations in this report include consideration of reducing

fines, or creating progressive or means-based fine structures, for various

low-level traffic violations. Within parameters set by the State, local

jurisdictions have discretion over the amount of fines and can set fines to

amounts below the State-allowed maximums for most infractions. As

such, the City may lower fines and/or create a progressive or means-

based fine structure as long as the new fine amounts comply with the

limitations set forth in the Vehicle Code.

3

See e.g., id. at §§ 830.33(c), 830.3(c)-(k), 830.38.

4

See, e.g., NAACP Legal Defense Fund Toolkit, August 2020 (summary); Police Union Contracts & Police Bill of

Rights Analysis, Campaign Zero, 2016 (summary).

5

See Meyers-Milias-Brown Act (“MMBA”) (Gov. Code § 3500 et seq.).

8

d. State Law Regarding Automated Traffic Enforcement

Although not reflected in the final recommendations, the task force

considered a recommendation related to automation of traffic

enforcement. State law permits automated systems at traffic light

intersections, commonly known as “red light cameras,”

6

however it

prohibits the use of automated systems to enforce speeding violations.

7

At this time, the City could only use automated enforcement for red light

violations, but not for speeding, unless there is a change in state law

E. Recommendations

Below is a summary of the recommendations developed by the community

advisory task force and consultant team (see Section V for a more detailed

summary of how the recommendations were developed). In framing the

recommendations, task force members acknowledged that robust community

engagement should be a guiding principle underpinning each action. Additional

research and analysis will also be needed before implementation. If the City

Council chooses to move forward with any of the recommendations listed below,

the City should engage in broad, authentic, and robust community engagement

before, during, and after implementation to ensure sustained community support.

These recommendations inform a set potential pilots described in Section V.C.

1. Prioritize Self-Enforcing Infrastructure

Increase and prioritize self-enforcing infrastructure investments (without

increasing surveillance) in high-injury network corridors, low-income

communities, and communities of color. This recommendation calls for

increased investment in “self-enforcing infrastructure,” which refers to road

features that naturally slow traffic and discourage drivers from breaking traffic

rules. These improvements increase safety and reduce the need for active

enforcement (See Appendix E for a Task Force-led literature review on this

topic).

2. Eliminate Police Enforcement of Non-Moving and

Equipment-Related Traffic Violations

LAPD’s 2022 Pretextual Stop Policy limits traffic enforcement to violations that

have a nexus to public safety. We recommend eliminating enforcement of all

non-moving and equipment-related traffic violations by police. Ultimately, the

goal of this recommendation is to limit interactions between police and

motorists by eliminating police enforcement of non-moving and equipment-

related violations. This recommendation expands on LAPD’s March 2022 policy

change,

8

which limits pretextual stops. It is also informed by policies enacted in

other cities like Philadelphia, where they limited the ability of police to stop

motorists for specific minor violations.

6

Vehicle Code § 21455.5(a).

7

Id. at § 40801.

8

Los Angeles Police Department (2022). “Policy – Limitation on Use of Pretextual Stops – Established.” Office of the

Chief of Police. Retrieved from:

<https://lapdonlinestrgeacc.blob.core.usgovcloudapi.net/lapdonlinemedia/2022/03/3_9_22_SO_No._3_Policy_Limitati

on_on_Use_of_Pretextual_Stops_Established.pdf>

9

3. Implement Alternative Traffic Fine and Fee Models

Consider alternative fine and fee models (e.g., means-based) that advance

traffic safety objectives and do not perpetuate enforcement disparities. This

recommendation aims to ensure that enforcement promotes traffic safety

objectives and does not reinforce disproportionate burdens for low-income

communities and communities of color. Alternatives to traffic fines can help

shift enforcement away from punitive fines and toward prevention. Where

possible, Council may consider a system where local fines for safety-related

infractions are tied to incomes, a practice that is used in other jurisdictions

globally.

4. Improve Local Officer Accountability Mechanisms

Identify local obstacles that limit officer accountability and reduce the ability of

the Chief of Police to discipline officers for misconduct (e.g., excessive use of

force, racial profiling, and other violations); identify strategies to overcome

these obstacles. This recommendation emphasizes the importance of enforcing

penalties for officer misconduct and the removal of local obstacles that limit

officer accountability and discipline.

10

5. Deploy Unarmed Civilians and Care-Centered Teams to

Address Traffic Safety Issues

Use unarmed civilians, who are focused exclusively on road safety, to enforce

safety-related traffic violations (e.g., speeding). Create care-based teams

responsible for responding to traffic-related calls for service. The main goal of

this recommendation is to transfer traffic enforcement responsibilities to

unarmed teams as a means of eliminating lethal and less-lethal weapons from

traffic enforcement. This recommendation also calls for unarmed teams of care-

centered, behavioral health specialists to respond to traffic-related calls for

service when a clear behavioral health issue is present. The proposed

recommendation builds on efforts in several cities reviewed for this study— (1)

Berkeley, California; (2) Oakland, California; and (3) Philadelphia,

Pennsylvania—that are working to transfer specific traffic enforcement

responsibilities to unarmed civilians.

11

I. CONTEXT AND FRAMING

A. Los Angeles City Council Motion and Impetus for

This Study

In 2020, the murder of George Floyd, a Black man, by a Minneapolis police

officer led to protests across the country, including in Los Angeles.

9

As a result of

local protests and persistent calls for non-law enforcement alternatives, the Los

Angeles City Council passed a motion in October 2020. The Council Motion (CF-

20-0875) directed the Los Angeles Department of Transportation (LADOT) to

conduct a study that evaluates opportunities for unarmed traffic enforcement in

the city.

Since the launch of this study in February 2022, several developments have

influenced the study’s findings and approach. In March 2022, the Los Angeles

Police Commission approved a policy limiting pretextual stops to safety-related

incidents and setting requirements for officers that pursue these types of stops.

10

11

Further, in October 2022, City Council approved a motion to explore an Office

of Unarmed Response and Safety for the city.

12

13

More recently, LAPD’s largest employee union noted that they are “looking to

have officers stop responding to more than two dozen types of calls, transferring

those duties to other city agencies while focusing on more serious crimes.”

14

9

City of Minneapolis. (2023). 38th and Chicago. 38th and Chicago - City of Minneapolis. Retrieved March 7, 2023,

from https://www.minneapolismn.gov/government/programs-initiatives/38th-chicago/

10

Rector, K. (2022, March 2). New limits on 'pretextual stops' by LAPD officers approved, riling police union. Los

Angeles Times. Retrieved March 7, 2023, from https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2022-03-01/new-limits-on-

pretextual-stops-by-lapd-to-take-effect-this-summer-after-training

11

Los Angeles Police Department (2022). “Policy – Limitation on Use of Pretextual Stops – Established.” Office of the

Chief of Police. Retrieved from:

<https://lapdonlinestrgeacc.blob.core.usgovcloudapi.net/lapdonlinemedia/2022/03/3_9_22_SO_No._3_Policy_Limitati

on_on_Use_of_Pretextual_Stops_Established.pdf>

12

Los Angeles City Council (2021). Council File: 20-0875 – Transportation Policy Objectives/Alternative Models and

Methods/Unarmed Law Enforcement. Council Adopted Item. Retrieved March 30, 2023, from

https://cityclerk.lacity.org/lacityclerkconnect/index.cfm?fa=ccfi.viewrecord&cfnumber=20-0875

13

KCAL-News Staff. (2022, October 8). La City Council to consider 'office of unarmed response'. CBS News.

Retrieved March 7, 2023, from https://www.cbsnews.com/losangeles/news/la-city-council-to-consider-office-of-

unarmed-response/

14

Zahnisher, D. (2023, March 1). LAPD should stop handling many non-emergency calls,the police union says. Los

Angeles Times. Retrieved March 20, 2023 from https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2023-03-01/lapd-officers-

want-to-stop-responding-to-nonviolent-calls

12

B. History and Origins of Traffic Enforcement

This report explores options for the City of Los Angeles to pursue “alternative

models and methods that do not rely on armed law enforcement to achieve

transportation policy objectives.”

15

In a motion presented to the Ad Hoc

Committee on Police Reform, councilmembers noted that the impetus for this

study is a legacy of racialized policing in the City of Los Angeles and nationwide,

where police officers “have long used minor traffic infractions as a pretext for

harassing vulnerable road users and profiling people of color.”

16

In keeping with

Council’s stated intent, this section offers an abridged overview of the history of

policing, beginning in the 20

th

Century with the advent of the automobile. This

history is not exhaustive; it is intended to ground readers in the larger historic and

social contexts that inform this report’s analysis and the accompanying

recommendations. Additional information can be found in Appendix R: History

and Origins of Traffic Enforcement.

1. How Cars Transformed Policing

The twentieth century saw the rise of the automobile as a primary mode of

travel; with it, came a transformation in how the public interacted with police

officers. In many respects, the ubiquity of the automobile – and the reliance on

armed law enforcement to address traffic safety concerns – meant that traffic

stops “became one of the most common settings for individual encounters with

the police.”

17

Driving presented new hazards in public spaces, leading local governments to

pass a raft of laws to regulate space, assign rights of way, and govern the use

of vehicles.

18

The language in these new laws was often vague. For example,

California’s Motor Vehicle Act of 1915 “prohibited driving ‘at a rate of speed . .

. greater than is reasonable and proper.’”

19

Determining what was considered

“reasonable” or “proper” necessarily relied on the discretion of the enforcing

body. But police enforcement of these norms was not a foregone conclusion,

with some police departments actively resisting the task of enforcing traffic

laws.

20

In some cases, “police chiefs complained that traffic control was ‘a

separate and distinct type of service’ – i.e., it was not their job.”

21

While

15

Los Angeles City Council (2021). Council File: 20-0875 – Transportation Policy Objectives/Alternative Models and

Methods/Unarmed Law Enforcement. Council Adopted Item. Retrieved March 30, 2023, from

https://cityclerk.lacity.org/lacityclerkconnect/index.cfm?fa=ccfi.viewrecord&cfnumber=20-0875

16

Los Angeles City Council (2020). Council File: 20-0875 – Transportation Policy Objectives/Alternative Models and

Methods/Unarmed Law Enforcement. Motion Document(s) Referred to the Ad Hoc Committee on Police Reform.

Retrieved March 30, 2023, from

https://cityclerk.lacity.org/lacityclerkconnect/index.cfm?fa=ccfi.viewrecord&cfnumber=20-0875

17

Seo, S. (2016). The New Public. Yale Law Journal. Retrieved on April 3, 2023 from

https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3825&context=faculty_scholarship: p. 1625

18

Seo, S. (2016). The New Public. Yale Law Journal. Retrieved on April 3, 2023 from

https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3825&context=faculty_scholarship: p. 1635

19

Seo, S. (2016). The New Public. Yale Law Journal. Retrieved on April 3, 2023 from

https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3825&context=faculty_scholarship: p. 1636

20

Seo, S. (2016). The New Public. Yale Law Journal. Retrieved on April 3, 2023 from

https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3825&context=faculty_scholarship: p. 1637

21

Seo, S. (2016). The New Public. Yale Law Journal. Retrieved on April 3, 2023 from

https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3825&context=faculty_scholarship: p. 1637

13

separate bureaucracies had been created to enforce certain types of laws

(e.g., postal inspectors and secret service agents), “a lack in political will to

foot the bill for yet another bureaucratic entity" meant that traffic regulation

would fall on the police.

22

This represented an expansion of police powers over the traveling public. It

embedded a system where traffic safety issues are first and foremost handled

by police, and it established the broad discretionary powers that police

departments use when enforcing voluminous and complex traffic safety laws.

Indeed, it represented a transformation in how police and policing showed up

in the daily lives of all Americans.

23

Given the history of law enforcement in the

U.S., the implications for marginalized groups (e.g., Black communities,

Indigenous populations, Latino communities, migrants, low-income

communities) were particularly dire.

C. Los Angeles’ Context

In Los Angeles, police brutality against Black residents during traffic stops has

been tied to multiple uprisings, leading to local, state, and national calls for police

reform. In the 1960s, the Watts Rebellion made headlines as part of the larger,

nationwide movement against police brutality. The arrest of a 21-year-old Black

man, Marquette Frye, for drunk driving close to the Watts neighborhood, and the

ensuing struggle, sparked six days of unrest. The uprising resulted in 34 deaths,

over 1,000 injuries, nearly 4,000 arrests, and the destruction of property valued

at $40 million.

24

As a result of the rebellions, Governor Jerry Brown appointed a

commission to study the underlying factors and identify recommendations in

various policy areas, including police reform. In its report, the Commission cited

the lack of job and education opportunities and the resentment of the police as

key contributors to the uprisings, which were ignited by the brutal actions taken

against Frye during the traffic stop.

25

The report also recommended a

strengthened Board of Police Commissioners to oversee the police department.

Likewise, the report supported recruiting more Black and Latino police officers as

a means of improving the community-police relationship.

26

Despite the lessons gleaned from the Watts Rebellion, the 1990s saw another

uprising in response to police brutality during a traffic stop. In 1992, Rodney King,

a 25-year-old Black man, was brutally beaten and arrested by four police officers

22

Seo, S. (2016). The New Public. Yale Law Journal. Retrieved on April 3, 2023 from

https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3825&context=faculty_scholarship: p. 1637-8

23

Seo, S. (2016). The New Public. Yale Law Journal. Retrieved on April 3, 2023 from

https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3825&context=faculty_scholarship: p. 1638

24

Stanford University. (2018, June 5). Watts Rebellion (Los Angeles). The Martin Luther King, Jr., Research and

Education Institute. Retrieved March 7, 2023, from https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/encyclopedia/watts-rebellion-los-

angeles

25

California. Governor's Commission on the Los Angeles Riots. (1965). Violence in the city: An end or a beginning?:

A report. HathiTrust. The Commission. Retrieved 2023, from

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433081793618&view=1up&seq=12.

26

California. Governor's Commission on the Los Angeles Riots. (1965). Violence in the city: An end or a beginning?:

A report. HathiTrust. The Commission. Retrieved 2023, from

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433081793618&view=1up&seq=12.

14

and later charged with driving under influence.

27

The four officers were charged

with excessive use of force, but were all acquitted one year later. The widely

circulated video of King’s beating and the news about the officers’ acquittal

ignited days of violent unrest in the city, especially in the Historic South Central

neighborhood. The city employed a curfew and the National Guard to respond to

the uprising. While the 1992 unrest shared parallels with the Watts uprisings, “the

conflagration that took hold after the King trial wasn’t constrained to that

neighborhood and was not restricted to Black Angelenos.”

28

Instead, the ensuing

unrest “constituted the first multiethnic class riot in American history, an eruption

of fury at the socioeconomic structures that excluded and exploited so many in

Southern California.”

29

In 2000 the City of Los Angeles entered a consent decree with the federal

government. Instead of fighting a federal civil rights lawsuit “alleging a ‘pattern-

and-practice’ of police misconduct, the Mayor, City Council, Police Commission,

and Police Department signed a ‘consent decree’ with the U.S. Department of

Justice, giving the Federal District Court jurisdiction to oversee the LAPD’s

adoption of a series of specific management, supervisory, and enforcement

practices.”

30

In an evaluation of the effectiveness of the decree, researchers

found that the strong police leadership and oversight brought by the consent

decree have made policing in Los Angeles more respectful and effective,

although there is still more to be done.

31

In 2009, 83 percent of residents

reported that LAPD was “doing a good or excellent job,” up from 71 percent two

years prior. In 2005, 44 percent of surveyed residents reported that the police

“treat members of all racial and ethnic groups fairly ‘almost all of the time’ or

‘most of the time.’”

32

By 2009, that figure increased to 51 percent. The underlying

reforms driving these changes included the following:

▪ Implementing new data systems to track officers’ performance and

proactively alert supervisors if there are indicators that officers are violating

protocol.

▪ Updating policies, rules, definitions, and management strategies to govern

the use of force by officers.

▪ Tracking stops “of motor vehicles and pedestrians, breaking down the

patterns by race and ethnicity, by the reasons for the stops, and by the

27

Krbechek, A. S., and Bates, K. G. (2017, April 26). When La erupted in anger: A look back at the Rodney King

Riots. NPR. Retrieved March 7, 2023, from https://www.npr.org/2017/04/26/524744989/when-la-erupted-in-anger-a-

look-back-at-the-rodney-king-riots

28

Muhammad, I. (2022). What Were the L.A. Riots? The New York Times Magazine. Retrieved on April 4, 2023 from

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2022/04/28/magazine/la-riot-timeline-photos.html

29

Muhammad, I. (2022). What Were the L.A. Riots? The New York Times Magazine. Retrieved on April 4, 2023 from

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2022/04/28/magazine/la-riot-timeline-photos.html

30

Stone, C., Foglesong, T., and Cole, C. M. (2009). (rep.). Policing Los Angeles Under a Consent Decree: The

Dynamics of Change at the LAPD. Harvard Kennedy School. Retrieved 2023, from

https://www.hks.harvard.edu/publications/policing-los-angeles-under-consent-decree-dynamics-change-lapd: 2.

31

Stone, C., Foglesong, T., and Cole, C. M. (2009). (rep.). Policing Los Angeles Under a Consent Decree: The

Dynamics of Change at the LAPD. Harvard Kennedy School. Retrieved 2023, from

https://www.hks.harvard.edu/publications/policing-los-angeles-under-consent-decree-dynamics-change-lapd.

32

Stone, C., Foglesong, T., and Cole, C. M. (2009). (rep.). Policing Los Angeles Under a Consent Decree: The

Dynamics of Change at the LAPD. Harvard Kennedy School. Retrieved 2023, from

https://www.hks.harvard.edu/publications/policing-los-angeles-under-consent-decree-dynamics-change-lapd: 1.

15

results of the stops in terms of crime detected” (like the data analyzed for this

study).

▪ Implementing new policies and management systems for the anti-gang unit

and other special divisions

33

With these updated systems in place, the LAPD reported reductions in use of

force incidents, while also seeing reductions in overall crime levels. While the

study notes significant improvements, the authors also provide caveats, noting

that there are “many LA residents, police officers, and arrestees who remain

deeply unhappy with the performance of the police department and who want to

see more improvement.” They also note that administrative data indicated some

uneven results; “for example, the use of force is down overall, but not in every

division.”

34

Still, the independent evaluation finds that the overall trend is positive,

with growing community trust and reduced use of force incidents overall.

33

Stone, C., Foglesong, T., and Cole, C. M. (2009). (rep.). Policing Los Angeles Under a Consent Decree: The

Dynamics of Change at the LAPD. Harvard Kennedy School. Retrieved 2023, from

https://www.hks.harvard.edu/publications/policing-los-angeles-under-consent-decree-dynamics-change-lapd: 5.

34

Stone, C., Foglesong, T., and Cole, C. M. (2009). (rep.). Policing Los Angeles Under a Consent Decree: The

Dynamics of Change at the LAPD. Harvard Kennedy School. Retrieved 2023, from

https://www.hks.harvard.edu/publications/policing-los-angeles-under-consent-decree-dynamics-change-lapd: 2.

16

II. PROJECT OVERVIEW

A. City Working Group

The City Working Group includes representatives from City of Los Angeles

departments named in the Council Motion (CF-20-0875) and directed by Council

to perform the work (See Appendix A for full Council Motion). Participating City

departments include Department of Transportation (LADOT), Police Department

(LAPD), City Administrative Officer (CAO), City Attorney, and Chief Legislative

Analyst (CLA). The City Working Group informed the development of the

Request for Proposals, supported LADOT in soliciting and selecting members of

the Traffic Enforcement Alternatives Advisory Task Force, and reviewed draft

project deliverables. LAPD, LADOT, and City Attorney’s Office consistently

attended Task Force meetings, made presentations to the Task Force on various

topics related to traffic enforcement, and provided data sources to the consultant

team to inform the quantitative and qualitative analyses. The City Attorney’s

Office attended Task Force meetings, provided legal guidance on an ongoing

basis, and guided LADOT on how to approach issues related to the Task Force

and the Brown Act. The working group were given the opportunity to review and

provide feedback at various stages of the study and project deliverables.

B. Consultant Team

The City Working Group selected the consultant team for this study. The team

consisted of the following firms with the associated scopes of work:

▪ Estolano Advisors: Consultant team project manager and responsible for

providing Task Force meeting facilitation support.

▪ Equitable Cities: Research team responsible for conducting a case study

literature review, quantitative analysis, and qualitative analysis.

▪ Nelson\Nygaard: Research team support responsible for leading the expert

interviews, supporting Equitable Cities with the focus groups, and identifying

next steps for outreach.

▪ Law Office of Julian Gross: Legal team responsible for conducting

interviews and research on legal questions arising from the study’s proposed

recommendations.

The consultant team developed the study and executed the scope of work

described above in collaboration with the City’s Traffic Enforcement Alternatives

Advisory Task Force (See Section III.C).

C. Traffic Enforcement Alternatives Advisory Task

Force

1. Background and Task Force Selection

The City Council motion directed LADOT to develop an advisory task force to

provide recommendations on traffic safety alternatives. The resulting Traffic

Enforcement Alternatives Advisory Task Force provided guidance and

feedback on the consultant team’s deliverables and co-developed study

17

recommendations with the consultant team. The Task Force met eleven (11)

times from June 2022 through August 2023.

The Task Force consisted of thirteen (13) members with personal and

professional experience in traffic safety, public health, mental health, racial

equity, academia, and criminal justice (See Appendix B for a full Task Force

roster). Members were selected through a two-step process, which began

with a Google Form application, followed by interviews with representatives

from the City Working Group (LADOT and LAPD) and the consultant team

(See Appendix C for the application form). To recruit participants, LADOT

conducted outreach via its existing listserv. The City received 76 applications

and interviewed 11 applicants to learn more information. The City Working

Group ultimately selected 13 applicants to serve as Task Force members.

Eight applicants were selected on the strength of their initial application; four

members went through an interview process conducted by the City Working

Group; and one member was appointed from the Community Police Advisory

Board (C-PAB). A minimum of three (3) slots were made available for

members of the C-PAB, but only one member expressed interest and

responded to the call to participate in the Task Force. The applicants were

selected based on selection criteria and score (See Appendix C for selection

criteria).

2. Public Task Force Meetings

The Task Force served as a public body, which required the City and

members to comply with requirements outlined in California’s Ralph M. Brown

Act. These requirements included ensuring that the City posted meeting

materials at least 72 hours prior to each meeting and providing time during

each meeting for public comment. Task Force members also needed to

identify a President and Vice President, whom they elected during the

September 2022 meeting (See Appendix B for elected members). Task Force

President and Vice President were responsible for facilitating meetings,

including calling for the start of each meeting, calling for votes, monitoring

timing for general public comment, and calling for meeting adjournment. The

consultant team facilitator was also available to facilitate specific agenda

items, dependent on the content.

To comply with the AB 361 requirements for teleconferencing for Brown Act

bodies, Task Force meetings took place on a roughly monthly basis and

lasted between 90 minutes and two hours. To kick start this project, the

research team and Task Force held preparatory meetings starting in June

2022. Meetings covered a range of topics related to the study, including the

following (See Appendix D for Task Force meeting summary):

▪ Task Force responsibilities and administrative requirements

▪ Problem statement discussion

▪ Review of and feedback on consultant team deliverables

▪ LAPD’s existing and new policies, including the March 2022 pretextual

stops policy

▪ Task Force-led self-enforcing streets literature review

▪ Review of draft study findings and recommendations

18

3. Task Force Research Subcommittee

To increase coordination with the consultant team and provide a dedicated

space for the Task Force to share input on consultant team deliverables,

members voted to create a Research Subcommittee during the November

2022 meeting. The committee, which consisted of five members, met five

times between December 2022 and March 2023. Meeting topics were closely

aligned with previous or upcoming Task Force meeting topics and were

designed to preview consultant team deliverables for feedback from this

smaller group prior to presentations to the full Task Force.

4. Self-enforcing Infrastructure Literature Review

During the October 2022 Task Force meeting, several members called for the

study to include discussion and recommendations related to self-enforcing

street design as a method of alternative traffic enforcement. The City’s initial

Task Order did not include an analysis of infrastructure-related policies as a

component of the study. Members emphasized that street design treatments

– including narrower streets, wider sidewalks, enhancements for pedestrian

crossings, protected bike lanes, landscaping, etc. – can compel individuals to

abide by traffic laws by using design interventions to slow traffic.

In response, the Task Force voted in November 2022 to produce a Task

Force-led literature review for the final study. One member led the

development of this study, with feedback from the Task Force and Research

Subcommittee at several touch points. The Task Force approved the final

literature review during the February 16, 2023 meeting (See Appendix E)

19

III. RESEARCH FINDINGS

The consultant team worked with the Traffic Enforcement Alternatives Advisory Task

Force, LADOT staff, and City stakeholders, to develop a research approach focused on

providing comprehensive and effective solutions to traffic enforcement disparities that

are responsive to Los Angeles’ unique context. As part of the study approach, the

consultant team worked with the Task Force to define and confirm the research problem

statement. The team utilized the problem statement to build out three main research

questions:

▪ What are other cities, counties, police departments, and governmental bodies doing

about traffic enforcement nationwide?

▪ What does the reported LAPD policing data show about near-recent (2019-2021)

traffic stops?

▪ How do Angelenos respond to the potential of removing traffic enforcement

responsibilities to an unarmed, civilian government unit?

The consultant team explored the research questions through a three-pronged approach

which included identifying case studies, analyzing quantitative data (e.g., data on traffic

stops, demographics, and outcomes), and examining qualitative data (i.e., community

stakeholder focus groups, expert interviews). The following section outlines the research

process, methodology, and findings.

The consultant team also conducted research and analysis regarding the legal

implications of the recommendations in this report. These findings are described at the

end of this section.

A. Case Study Review Findings

1. Purpose

The consultant team conducted a nationwide scan of publicly available

literature and sources that focused on innovative and emerging international,

U.S. state, and local policies, programs, and initiatives aimed at eliminating

discriminatory and biased traffic safety and enforcement. The case study

review sought to answer the research question: “What are other cities,

counties, police departments, and governmental bodies doing about traffic

enforcement nationwide?”

The purpose of this scan was to compile a set of example cities where city

agencies had or were exploring various approaches to transitioning, reducing,

or limiting traffic enforcement. Upon review by LADOT, LAPD, and the Task

Force, a few cities were identified for further exploration through expert

interviews. The expert interview findings are detailed in Section IV.D. of this

report.

2. Methodology

The case studies focused specifically on preventative measures to limit

interactions between residents and police under the premise of traffic or

20

vehicle-related stops. The consultant team categorized the identified case

studies into the following tiers:

▪ Tier 1: Government at-large has transitioned powers of police enforcement

to a Department of Transportation (DOT) or another municipal unit.

▪ Tier 2: Government at-large is in the process of transitioning powers of

police enforcement to DOT or another municipal unit.

▪ Tier 3: Government entities have made policy or protocol changes to

reduce traffic safety enforcement via other means such as banning minor

traffic enforcement, non-police alternatives, or decriminalizing minor traffic

violations.

▪ Tier 4: Government entities are exploring either of the tiers above but have

not implemented anything to date.

▪ Tier 5: Non-governmental entities have examined how to decriminalize

mobility through guidelines, reports, podcasts, etc.

The tiers are organized based on the status of actions taken to mitigate traffic

enforcement. Tiers 1 and 2 include case studies where the city, state, or

county has or is actively transitioning police powers of traffic enforcement to a

non-police alternative. Tiers 3 and 4 outline case studies where a

governmental entity, such as the police department, has or is actively reducing

or limiting the extent of traffic enforcement within their jurisdiction. Altogether,

Tiers 1 through 4 can be considered as examples of top-down efforts to

ameliorate harm in traffic enforcement. Tier 5 includes case studies of non-

governmental organizations that are calling for changes in traffic enforcement

through guides, reports, tools, etc. These case studies can be considered as

examples of formal, organized community efforts to advocate for changes in

traffic enforcement practices. It should be noted that the search included traffic

enforcement of all individual transportation mode types, including people using

mobility devices, public transit, bicycling, walking, and driving.

3. Findings

The case studies were organized into tiers based on the degree to which the

city, state, county, or other governmental agency has made efforts to reduce,

limit, or transition traffic enforcement to non-police alternatives. Where

available, this report includes any concrete outcomes or independent analyses

of a program or policy’s effectiveness. Many of the case studies are in-

progress or newly-implemented, so outcomes are not fully documented.

Case studies in New Zealand (Tier 1) and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (Tier 2)

represent the most advanced examples of harm reduction through shifts in

power for traffic enforcement. Both governmental bodies decided to use non-

police alternatives to enforce certain types of traffic laws. In New Zealand,

non-moving violations and minor moving violations were enforced by the

Traffic Safety Service, a civilian governmental unit, for 30 years. While the unit

has since merged with the New Zealand Police, the case study shows that

specific traffic enforcement duties can be conducted successfully by unarmed,

civilian units.

21

In Philadelphia, city leadership and residents voted to move towards an

adaptation of the New Zealand example where minor traffic violations are

enforced by unarmed public safety “officers” housed within the Department of

Transportation. Philadelphia restructured traffic violations into “primary” and

“secondary” classifications and prohibited police from making traffic stops for

“secondary” traffic violations.

35

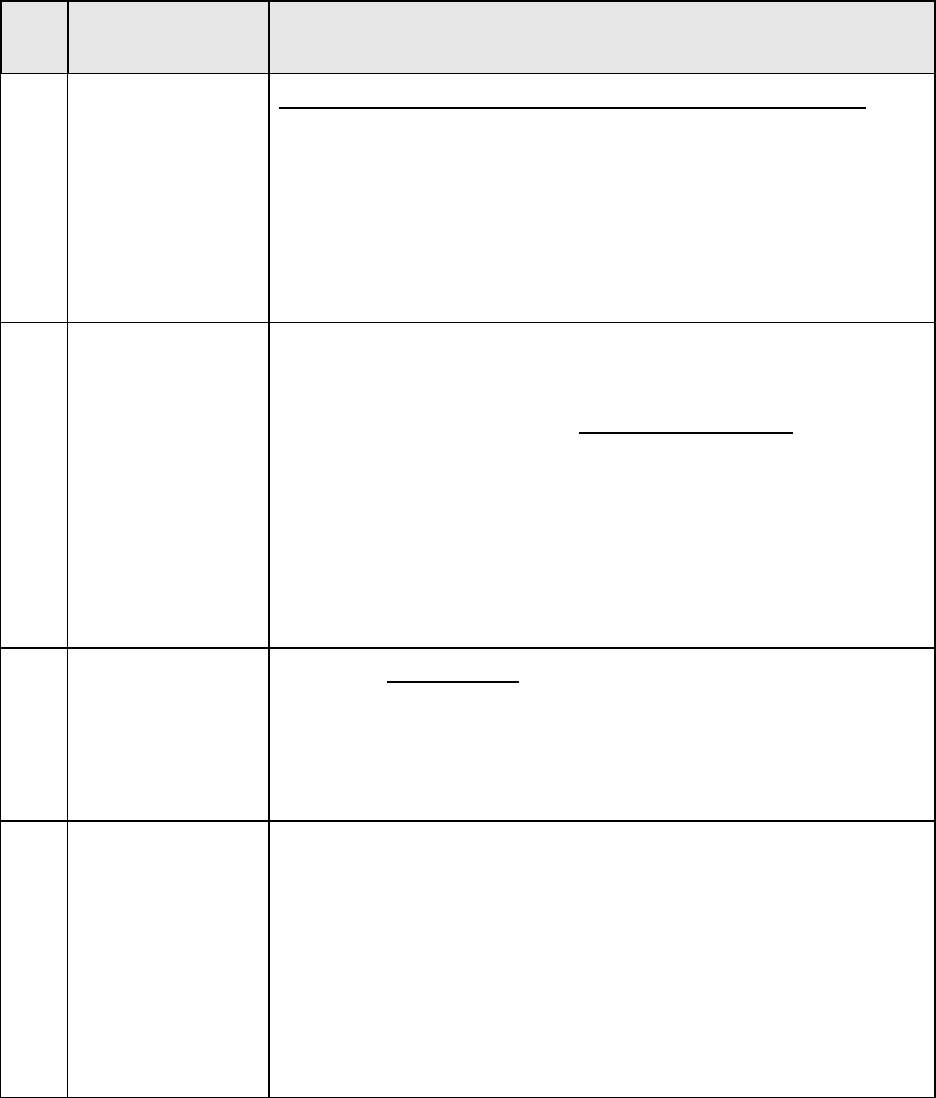

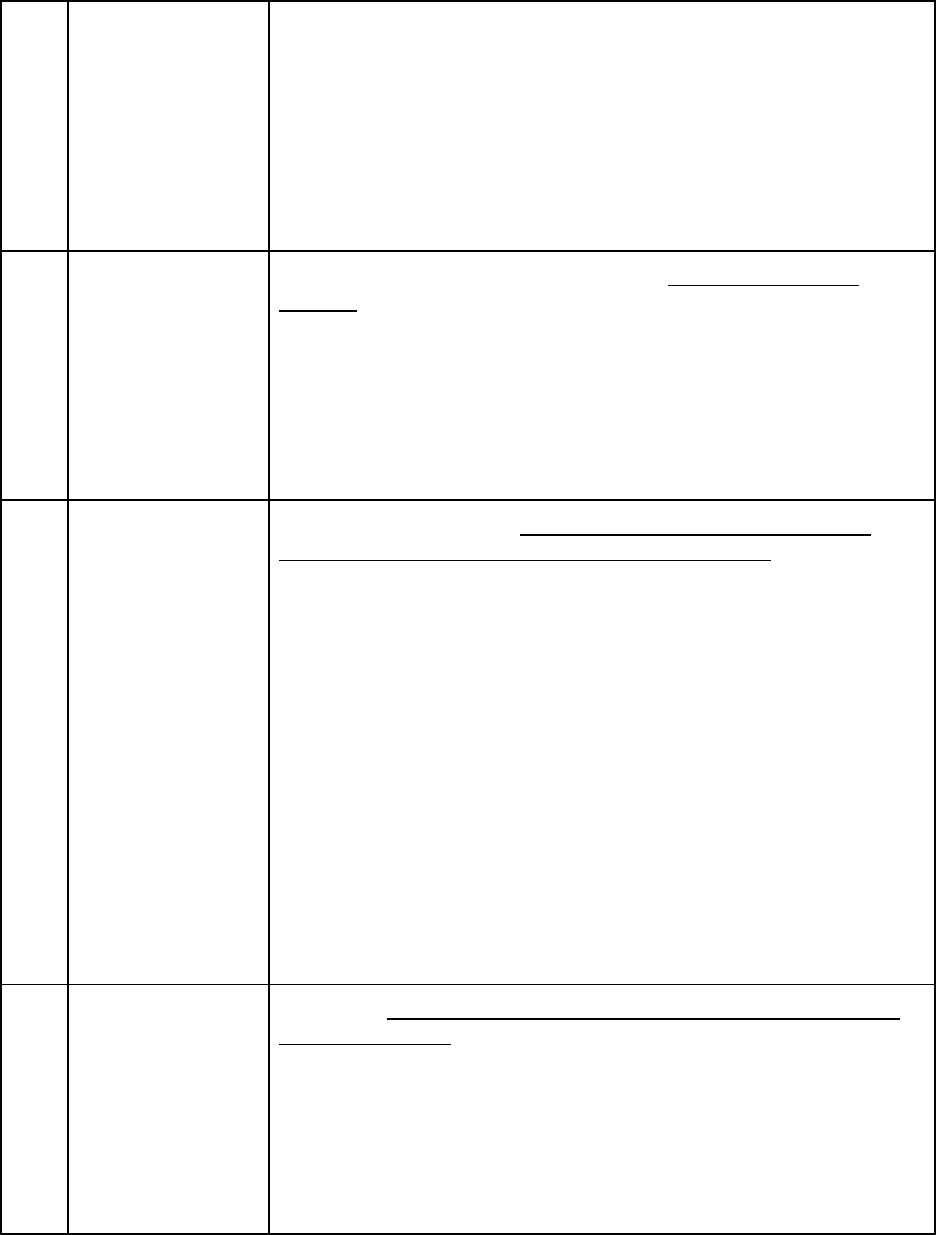

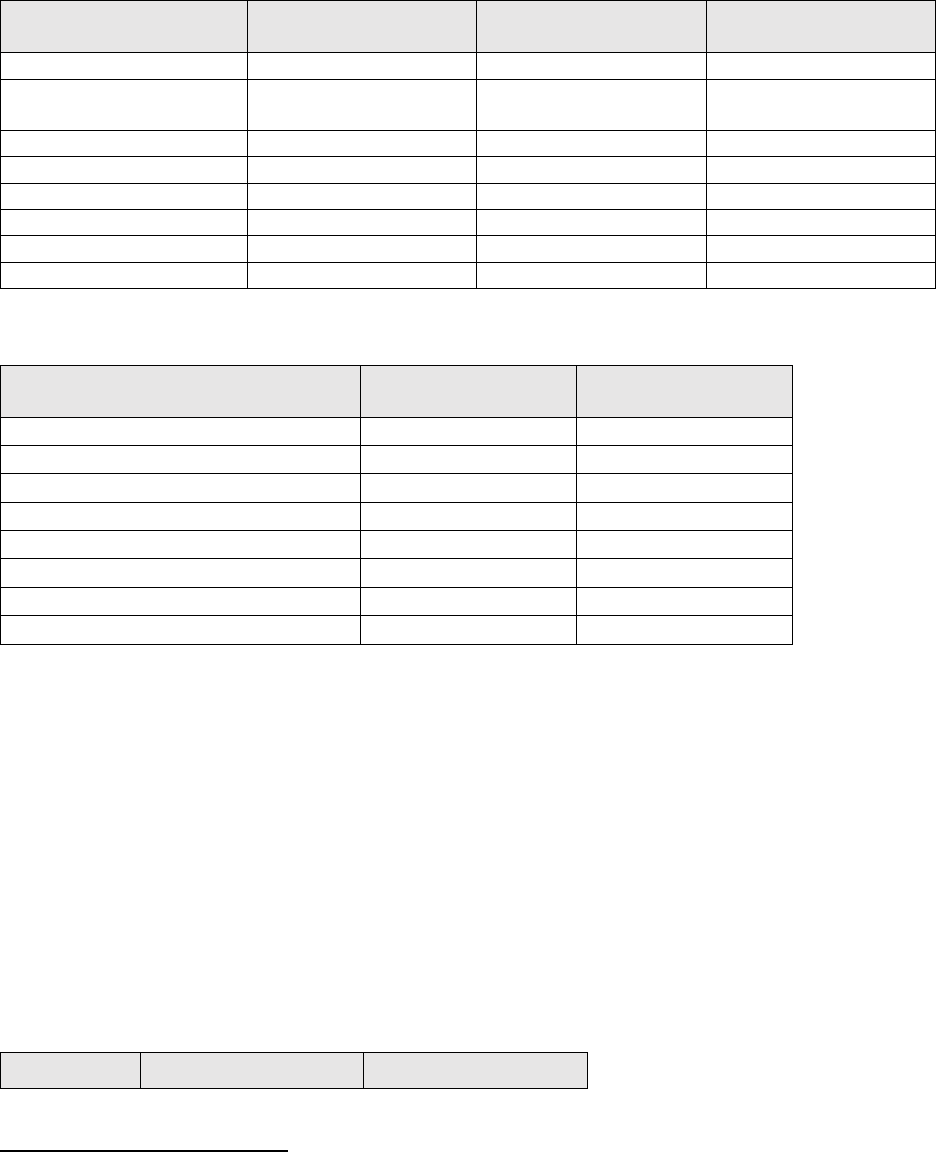

Table 1: Tiers 1 and 2 Case Studies

Tier

Location

Key Findings, Policy, Program or Funding Considerations

1

New Zealand

Nationwide, New Zealand used a non-police governmental

agency to enforce traffic laws between 1936 and 1992. The

agency was tasked with traffic enforcement of non-moving

violations and minor moving violations. The non-police

governmental agency dissolved due to the personnel costs, not

traffic safety concerns, associated with maintaining the agency.

It is important to note that the financial constraints were a result of

staffing the non-police governmental agency with transferred

police officers and not hired civilians. Traffic enforcement remains

a responsibility of the New Zealand Police, though it should be

noted that New Zealand Police “do not normally carry guns” on

their person.

2

Philadelphia, PA

Under the Driving Equality Act, police are permitted to make traffic

stops for “primary” violations that compromise public safety but

stops will no longer be used for “secondary” violations, like a

damaged bumper or expired registration tags.

There are several examples of cities, states, counties, or other governmental

units that have decided (Tier 3) or are considering (Tier 4) limits, reductions, or

restrictions in traffic enforcement. A bulk of Tier 3 case studies in the U.S.

have altered enforcement practices or policies to reduce the number of

potential traffic stops. In several examples, this looks like prohibiting police

from making traffic stops solely for non-moving violations – such as a broken

taillight – or decriminalizing driving with a suspended license if the reason for

suspension was solely for late or non-payment of fines. In addition, other Tier

3 case studies include governmental entities that have repealed or amended

laws to decriminalize specific types of traffic violations. By doing so, the

potential for pretextual stops by police is decreased overall. The case studies

in Tier 4 represent governmental entities that have reviewed police reform

recommendations or city-appointed task forces that have provided formal

35

The City of Philadelphia Code §12-1702 defines ”primary“ violations as any violation within the Pennsylvania

Vehicle Code that is not defined as a “secondary“ violation. “Secondary“ violations, defined within the City of

Philadelphia Code §12-1702, reference specific provisions of the Pennsylvania Vehicle Code, including Title 75 Pa.

C.S. § 1301, Registration of Vehicles; § 1310.1(c), Temporary Registration Permits; § 1332(a), Display of

Registration Plate; § 4302, Periods For Requiring Lighted Lamps; § 4524(c), Other Obstruction; § 4536, Bumpers; §

4703, Operation of Vehicle Without Official Certificate of Inspection; and, § 4706(c)(5), Unlawful Operation Without

Evidence of Emission Inspection. https://codelibrary.amlegal.com/codes/philadelphia/latest/philadelphia_pa/0-0-0-

285759

22

recommendations for police reforms. These examples explicitly outline

recommendations to limit, reduce, or transition traffic enforcement from police

to non-police alternatives.

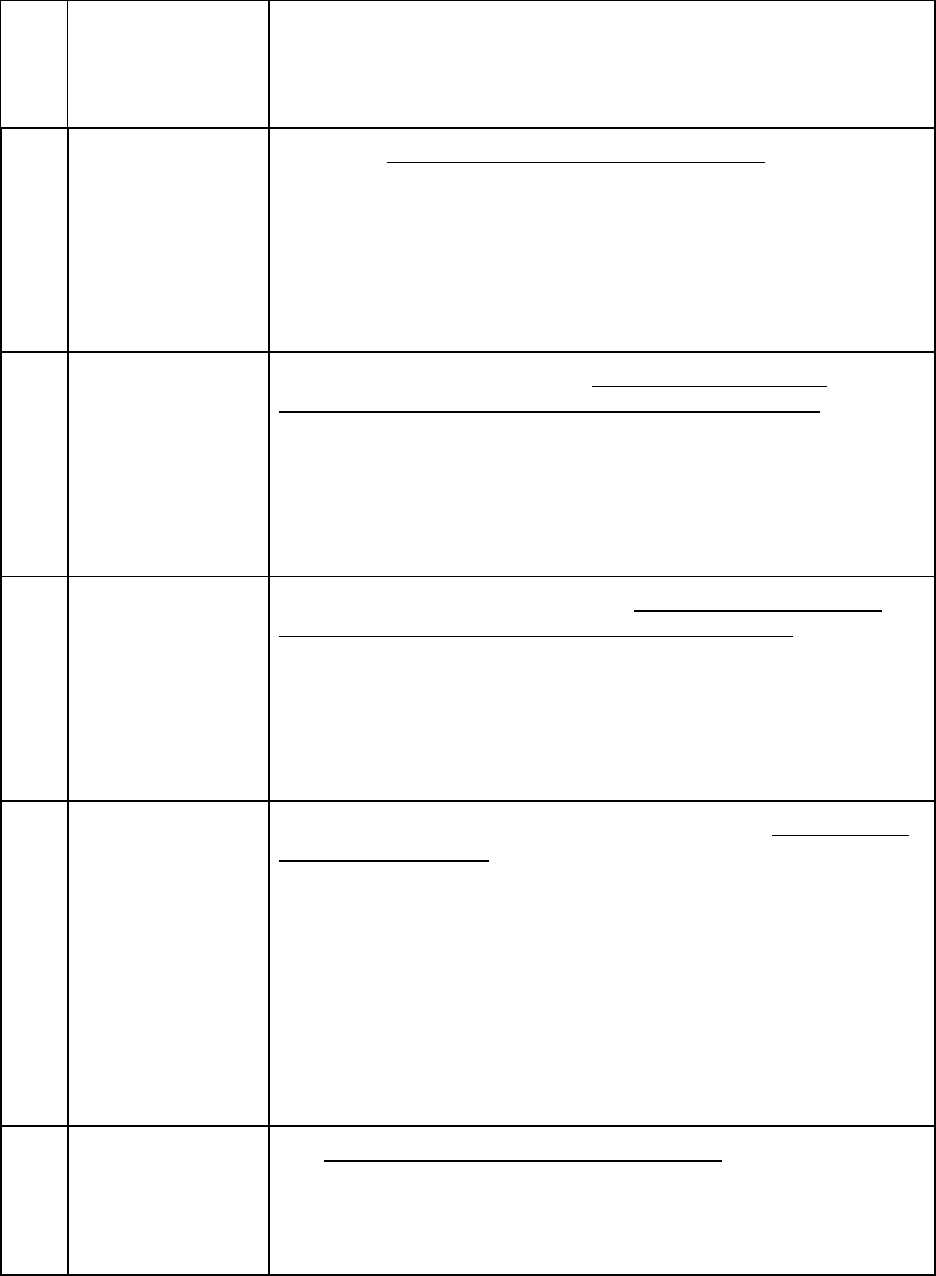

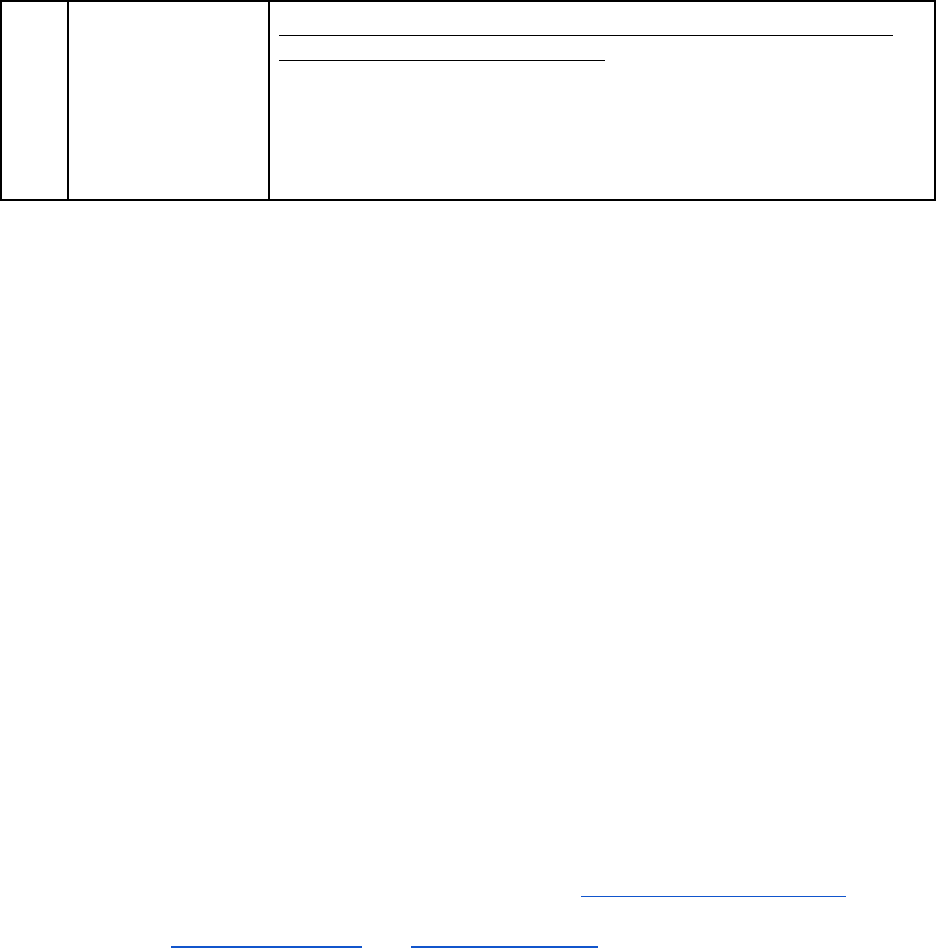

Table 2: Tiers 3 and 4 Case Studies

Tier

Location

Key Findings, Policy, Program or Funding Considerations

3

Berkeley, CA

The City of Berkeley passed a package of reforms in February

2021 that included prohibiting police from making traffic stops for

minor traffic infractions. The reforms include requiring written

consent for searches, precluding police from asking about parole

or probation status in most circumstances, looking into the legality

of reviewing officers’ social media postings to fire officers who

post racist content, and implementing an “Early Intervention

System” to get biased officers off the street.

3

Oakland, CA

Oakland City Council passed the 2021-2023 Fiscal Year budget in

May 2021 with several items for investing in policing alternatives.

The list included shifting some traffic enforcement responsibilities

to the Oakland Department of Transportation (OakDOT). The

OakDOT is reorganizing its parking division and is now

responsible for identifying and towing abandoned cars, as of April

2022. In addition, the approved budget also dedicates funds for

an audit of the Oakland Police Department (OPD), including a

goal to assess the feasibility of transitioning minor traffic

enforcement duties to civilian traffic officers. It should be noted

that OPD significantly reduced traffic stops related to minor traffic

violations by changing internal policy in 2016, which resulted in

traffic stops of Black drivers decreasing from 61% to 55% in three

years.

3

Pittsburgh, PA

The Pittsburgh City Council voted in December 2021 to prohibit

traffic stops for “secondary traffic violations,” such as broken

taillights or outdated registrations under a 60-day grace period--

meaning that a driver won't be pulled over for expired registration

unless the registration is more than 60 days out of date.

3

Seattle, WA

The Seattle Police Department updated traffic enforcement

practices based on recommendations from an equity-focused

working group. As of January 2022, Seattle Police are not allowed

to conduct traffic stops solely for minor, non-moving traffic

violations. The list of infractions that officers won't actively ticket

include:

● Vehicles with expired license tabs.

● Riders who are not wearing a bike helmet.

● Vehicles with a cracked windshield.

● Items hanging from a vehicle's rear-view mirror.

23

3

Portland, OR

The City of Portland, OR no longer allows police to conduct traffic

stops for non-moving violations that do not present an immediate

public safety threat, as of June 2021. Police are still allowed to

make stops for moving violations and stops related to ongoing

investigations.

3

King County, WA

Residents and visitors in the City of Seattle are no longer required

to wear a helmet while riding a bicycle. The King County Board of

Health voted in February 2022 to repeal its mandatory helmet

laws to reduce the potential for traffic stops related to the law.

3

Minneapolis, MN

The Minneapolis City Council passed a directive to city staff to

form an unarmed Traffic Safety Division housed outside of the

Police Department. Minneapolis began operating with new

policies on traffic enforcement in August 2021. Police Chief

Arradando is instructing officers not to stop drivers for minor traffic

violations. The Minneapolis City Attorney’s Office will no longer

prosecute people for driving with a suspended license, so long as

the sole reason for the suspension is failure to pay fines and fees.

3

Lansing, MI

The City of Lansing enacted new traffic stop guidelines in July

2020 to restrict officers from stopping drivers solely for secondary,

or non-moving, traffic violations. Police would still be able to

conduct a traffic stop if it is associated with a primary traffic

violation and a public safety risk.

3

Colorado

The state of Colorado passed a law in March 2022 that allows

bicyclists to conduct an “Idaho Stop” at intersections unless

otherwise stated. An “Idaho Stop” is generally a practice where

bicyclists can treat stop-signed intersections as stop-as-yield.

3

Nevada

The state of Nevada passed bills in 2021 that end license

suspensions solely for failure to pay fines and fees, and convert

minor traffic violations, such as broken taillights, from criminal

offenses into civil offenses. The change in license suspension

rules went into effect in October 2021, and the decriminalization of

minor traffic offenses will go into effect in 2023.

3

Idaho

The state of Idaho amended state law in 2018 to shift first or

second-time driver’s license violations from criminal infractions to

civil infractions, punishable by fines. In addition, violations for

driving with a suspended license are considered civil violations for

specific minor offenses, such as the failure to pay fines.

3

Virginia

The state of Virginia amended its laws to end debt-based license

suspensions in 2020. To address pretextual stops, Virginia

passed HB 5058 and SB 5029, which prohibit law-enforcement

officers from using common traffic and pedestrian violations as a

primary offense for stopping people for things such as jaywalking

or entering a highway where the pedestrian cannot be seen, as

24

well as vehicles with defective equipment, dangling lights, or dark

window tint. The laws took effect on March 1, 2021.

3

Brooklyn Center,

MN

The Brooklyn Center City Council voted in May 2022 to approve a

police reform package, which includes restricting police from

making minor traffic stops for non-moving violations, unless

required by law.

3

Kansas City, MO

The Kansas City City Council repealed municipal codes in May

2021 that allowed residents to be stopped by police for jaywalking

(Sec. 70-783), not having a clean bike wheel or tires “which carry

onto or deposit in any street, highway, alley or other public place,

mud, dirt, sticky substances, litter or foreign matter of any kind”

(Sec 70-268), or for a bicycle inspection “upon reasonable cause

to believe that a bicycle is unsafe or not equipped as required by

law, or that its equipment is not in proper adjustment or repair”

(Sec. 70-706).

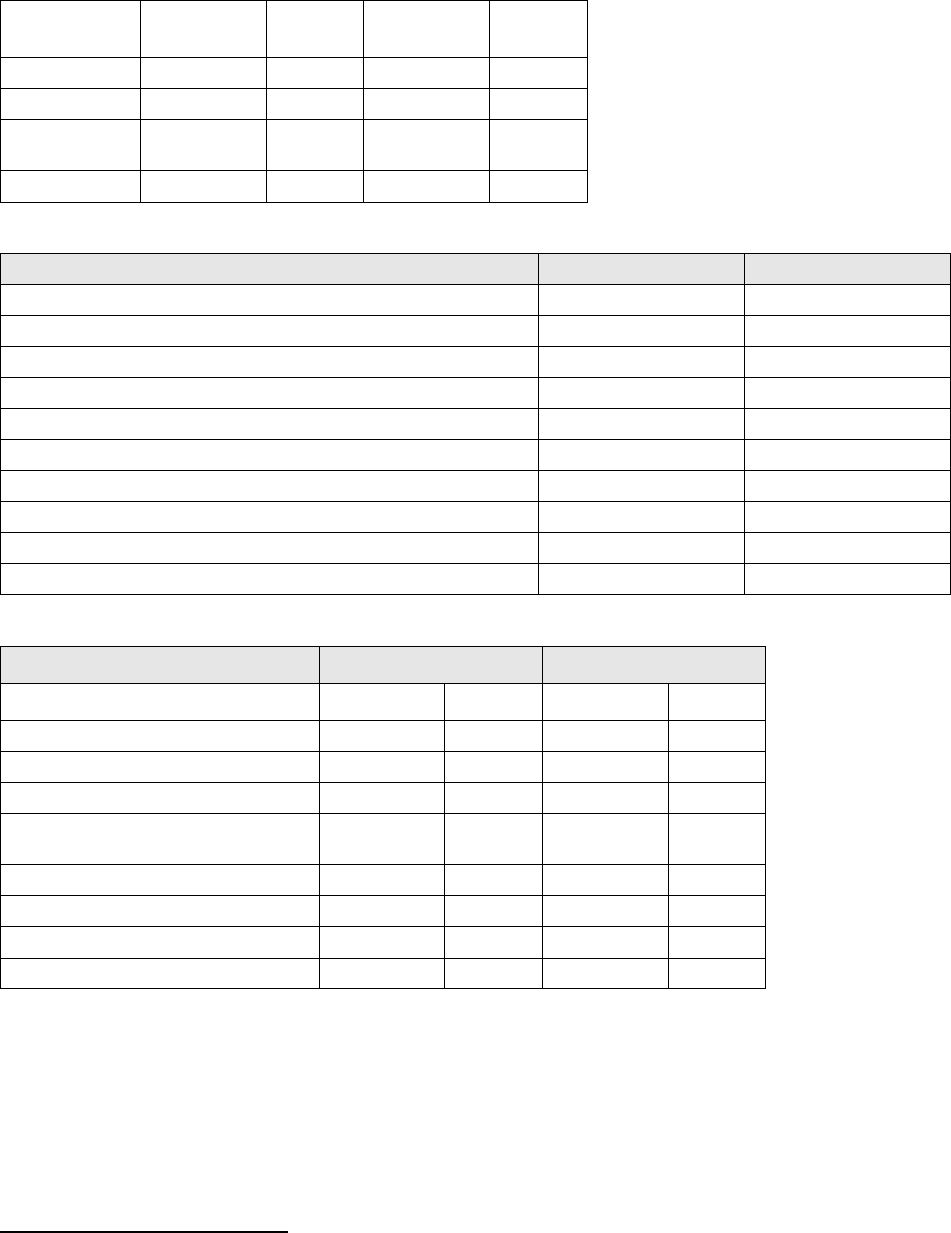

Tier

Location

Key Findings, Policy, Program or Funding Considerations

4

Washington, DC

The Police Reform Commission of Washington, DC

recommended several alternative policing methods for traffic

enforcement in DC. The recommendations included prohibiting

traffic stops and repealing or revising traffic laws for violations that

are not an immediate threat to public safety; restricting police to

approved pretextual stops for violent crimes; prohibiting safety

compliance checkpoints; and transferring police power for

enforcing non-threatening traffic violations to non-police municipal

units.

4

Denver, CO

A police reform task force in Denver provided many

recommendations to minimize unnecessary police interactions

with residents, including several that specifically address traffic

enforcement. Recommendations include decriminalizing minor

traffic violations that are often used for pretextual stops,

prohibiting searches during vehicle stops for minor offenses or

traffic violations, and shifting police power in traffic enforcement to

non-police alternatives. The following recommendations call for a

fundamental shift in the way traffic stops are handled:

● Decriminalize traffic offenses often used for pretextual

stops.

● Prohibit Denver Police from conducting searches in

relation to petty offenses or traffic violations.

● Remove police officers from routine traffic stops and crash

reporting and explore non-police alternatives that

incentivize behavior change to eliminate traffic fatalities.

● Eliminate the need for traffic enforcement by auditing and

investing in the built environment to promote safe travel

behavior.

25

● Invest in a community-based, community-led violence

prevention strategic plan that includes, but is not limited to,

traffic stop violence and government sanctioned violence.

4

Austin, TX

The Reimagining Public Safety Task Force in Austin, TX released

a report with several recommendations, including shifting traffic

violations to non-police trained professionals, decriminalizing

traffic offenses, and disarming traffic control officers.

4

Cambridge City

The Cambridge City Council is considering alternatives to traffic

enforcement. A proposal reviewed by the City Council would shift

traffic stop duties from police to unarmed, trained city staff.

4

New York City

In March 2021, The New York City Council approved a bill (File

No. Int 2224-2021) that would move the responsibility of traffic

crash investigations to the New York Department of

Transportation. The intent is to allow officers to “focus on more

serious crimes” and shift some responsibilities from the police to

civilian municipal units. A separate bill (File No. Int 1671-2019)

within the same reform package was also approved in March

2021. It requires a quarterly report on all vehicle stops, including

disaggregated demographic data, from NYPD.

4

Connecticut

The State of Connecticut passed a Police Accountability Bill in

2020 that prohibits police from asking for consent to search the

vehicle when conducting traffic stops. However, this does not

prevent a vehicle search altogether if the driver gives unsolicited

consent or the police acts upon probable cause. Additionally, the

bill directed the Police Transparency and Accountability Task

Force to consider whether traffic violations should be reclassified

into a primary-secondary system.

4

Los Angeles

County, CA

A motion by supervisors Hilda L. Solis and Janice Hahn requested

that the Board of Supervisors direct the Director of Public Health

to collaborate with Public Works, Sheriff’s Department, County

Counsel, California Highway Patrol, Los Angeles County

Development Authority, and the Los Angeles County Superior

Court to begin implementing the Vision Zero Action Plan

recommendations. A Vision Zero Action Plan was adopted by the

Los Angeles County Board of Directors to reduce the number of

unincorporated roadways and traffic fatalities by 2025. Some

recommendations include:

● Immediately implement the following recommendations

included in the County’s Vision Zero Action Plan in

partnership with community stakeholders:

o B-2: Identify process and partners for establishing

a diversion program for persons cited for infractions

related to walking and bicycling.

26

o B-3: Identify process and partners to consider

revising the Los Angeles County Municipal Code to

allow the operation of bicycles on sidewalks.

● Identify any other recommendations included in the Vision

Zero Action Plan that should be implemented in

partnership with community stakeholders to further

decriminalize and enable the use of non-vehicular and

alternative modes of transportation in unincorporated

communities.

● Instruct the Director of Public Health, in consultation with

the Chief Executive Office and relevant County

departments, to develop cost estimates and identify

funding needs and potential opportunities to support the

implementation of these Vision Zero recommendations.

4

San Francisco

The San Francisco Police Commission passed a policy to ban

police from making nine different types of pretextual stops. The

first draft of the policy had proposed 18 types of stops, but the

final policy removed five of them and edited seven for additional

specificity. It should be noted that this policy would still allow

police to make stops for the nine enumerated reasons, but in

limited circumstances.

4

Los Angeles, CA

The Los Angeles Police Department approved a pretextual stop

policy in February 2022 which prevents officers from initiating a

stop solely for a minor traffic violation. LAPD officers are still

allowed to make pretextual stops but must do so without basing it

“on a mere hunch or on generalized characteristics such as a

person’s race, gender, age, homeless circumstance, or presence

in a high-crime location.” (LAPD Departmental Manual, Policy

240.06)

4

Fayetteville, NC

In 2013, Police Chief Medlock of Fayetteville shifted traffic

enforcement in the department away from non-moving violations

and encouraged officers to focus on moving violations of

immediate concern to public safety. The number of investigative

stops for non-moving violations decreased dramatically for the

next four years, as did the number of Black drivers stopped and

searched. Peer-reviewed research using data from the

Fayetteville, NC case study shows that such changes in traffic

enforcement practices reduced traffic fatalities overall because

police were focused on moving traffic violations of immediate

danger to public safety, such as speeding (Fliss et al, 2020).

Finally, examples of non-governmental organizations (Tier 5) that have

produced reports directly related to reducing, limiting, or transitioning powers

of traffic enforcement from police to non-police alternatives represent calls

for action across the U.S. Tier 5 examples use case studies and evidence-

based practices to support their recommendations. The audience for these

reports range from formal governing bodies to community members. While

27

these reports do not formally or immediately impact traffic enforcement

practices, they include deeper and, in some cases, localized

recommendations. They can have a direct impact on local needs by

presenting supporting data and the lived experiences of people who are

affected by inequitable traffic enforcement.

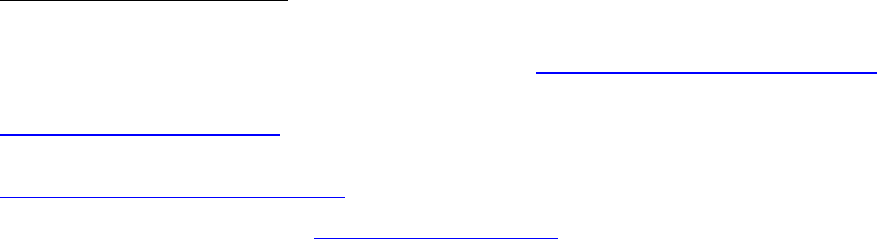

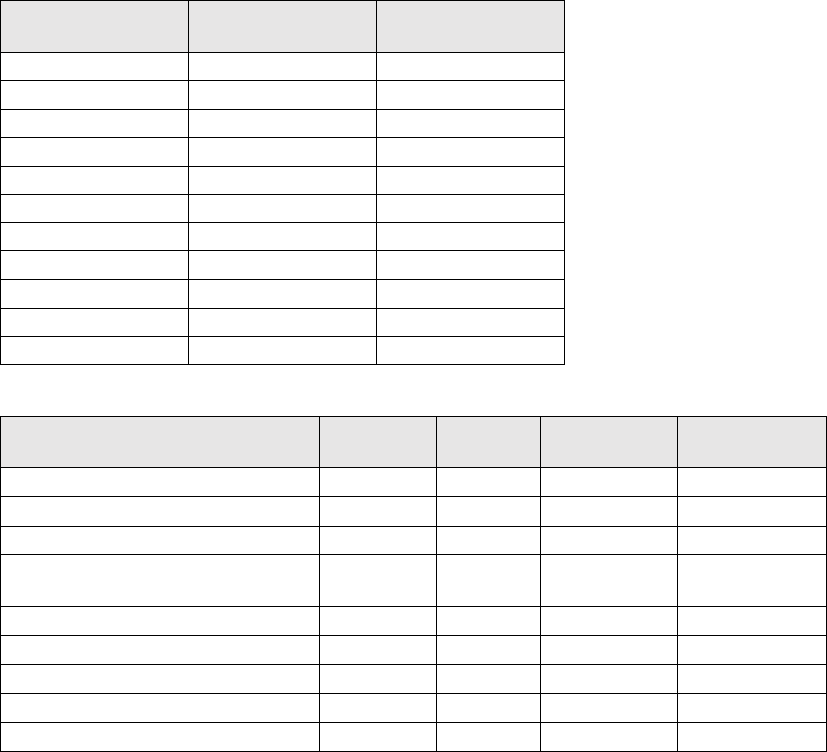

Table 3: Tier 5 Case Studies

Tier

Location

Key Findings, Policy, Program or Funding Considerations

5

Promoting Unity,

Safety & Health in

Los Angeles (Los

Angeles)

Promoting Unity, Safety & Health in Los Angeles (PUSH LA),

works to end the LAPD’s use of pretextual stops to racially profile

low-income communities of color and immediate removal of the

LAPD’s Metro Division from South Los Angeles. Their

recommendations include ending the use of pretextual stops,

removing LAPD’s Metro Division from South LA, improving traffic

safety through urban design, equitably addressing the root causes

of traffic safety issues, holding officers accountable for

misconduct, and banning vehicle consent searches.

5

Alliance for

Community

Transit (Los

Angeles)

Various policy research, advocacy, and community organizing

efforts were undertaken by the Alliance for Community Transit -

Los Angeles (ACT-LA) member organizations, partners, and allies

to develop an informed report, Metro As A Sanctuary. This

includes a community and healthy framework presented for Metro

to shift away from policing and create a more equitable and safe

transportation system centering on communities of color and

those with disabilities. This presents alternative crime prevention

measures and methods that do not center police enforcement.

Also, recommendations are split into multiple categories: care-

centered special tactics, stewardship, programming, support

services, public education, and job creation potential.

5

TransitCenter

(San Francisco,

Portland,

Philadelphia)

The report Safety For All by TransitCenter portrays how agencies

like BART in San Francisco, TriMet in Portland, and SEPTA in

Philadelphia are addressing safety concerns by hiring unarmed

personnel, developing high profile anti-harassment campaigns,

and better connecting riders to housing and mental health

services.

5

Kansas City, MO

BikeWalkKC in collaboration with the National Safe Routes

Partnership, co-authored the Taking on Traffic Laws: A How-To

Guide for Decriminalizing Mobility as a starting point for advocates

and communities interested in decriminalizing traffic violations

related to walking and biking. It draws upon the lessons learned

from BikeWalkKC’s experience successfully advocating for

legislation to decriminalize walking and biking in Kansas City. The

guide covers three key areas:

● The need to repeal laws leading to racialized traffic

enforcement

28

● How BikeWalkKC successfully advocated legislation to

decriminalize mobility in Kansas City.

● A Call to Action lays out steps advocates can take in their

own communities.

5

The Justice

Collaboratory-

Yale Law School

(New Haven, CT)

The report Principles of Procedurally Just Policing by Yale Law

School’s Justice Collaboratory explores the inequities surrounding

investigatory stops. The Supreme Court ruling in the Terry case,

which sought to promote crime prevention, approved police stops

on less than probable cause. Despite the ruling’s intent,

investigatory stops have continued to cause public distrust of

police due to a lack of transparency concerning policies and

policymaking processes.

5

Active

Transportation

Alliance (Chicago,

IL)

Active Transportation Alliance’s Fair Fares Chicagoland:

Recommendations for a More Equitable Transit System report

explores decriminalizing fare evasion arrests. Additionally, it

proposes ways to create a more equitable fare structure, including

a reduced transit fare program for low-income residents, fare

capping, and integrating transfers from the Chicago Transit

Authority (CTA), Pace Suburban Bus (Pace), and Metra

Commuter Rail (Metra).

5

Community

Service Society

(New York City)

Community Service Society’s report The Crime of Being Short

$2.75: Policing Communities of Color at the Turnstile explores

arrests of low-income New York City residents who are unable to

pay the fare for public transit. The report focuses on the arrests as

an example of broken windows policing. The report proposes

decriminalizing fare evasion, using city resources to help low-

income riders instead of arrests, and deinstitutionalized broken

windows and enforcement quotas.

5

The Ferguson

Commission (St.

Louis, MO)

Addressing racial disparities in municipal warrants The Ferguson

Commission’s Report entails calls to action related to municipal

warrants including those that would decrease the negative

consequences of receiving a municipal warrant. These calls to

action include creating a municipal court “Bill of Rights,”

communicating rights to defendants in person, providing

defendants clear written notice of court hearing details, opening

municipal court sessions, eliminating incarceration for minor

offenses, canceling failure to appear warrants, developing new

processes to review and cancel outstanding warrants, scheduling

regular warrant reviews, and providing municipal court support

services.

5

Center for Policing

Equity- Yale

University (New

Haven, CT)

The Redesigning Public Safety: Traffic Safety report outlines five

overarching themes of recommendations to ameliorate and

address harm caused by traffic violence. These include ending

pretextual stops, investing in public health approaches to road

safety, limiting use of fines and fees, piloting alternatives to armed

29

enforcement, and improving data collection and transparency. The

report utilizes peer-reviewed journal articles and local examples to

support or describe each recommendation. The recommendations

are primarily focused on the issue of traffic safety, and the “harms

caused by unjust and burdensome enforcement, including the

preventable debt, justice system entanglement, and trauma that

too often flow from a single routine traffic stop.” The Center for

Policing Equity’s white paper on traffic safety is one of several

publications in the Redesigning Public Safety series of papers.

5

The Vera Institute

of Justice

(Brooklyn, NY)

The Vera Institute of Justice’s report on The Social Costs of

Policing aims to describe police interactions, both at an individual

level and a community level. The report utilizes peer-reviewed

articles to support and detail the social costs of policing within four

main facets: (1) health, (2) education, (3) economic well-being,

and (4) civic and social engagement. By describing the social cost

of policing, the report underlines evidence for policymakers to

include when considering public safety investments or the costs

and benefits of police reform.

5

America Walks

(nationwide)

America Walk’s webinar How to Take on Harmful Jaywalking

Laws - Decriminalizing Walking for Mobility Justice includes expert

panel members working at the state and local level to

decriminalize jaywalking. Kansas City, Virginia, and California

recently decriminalized jaywalking. The authors explore data and

lived experiences, showing that police disproportionately enforce

these laws in Black, Indigenous, and people of color communities,

causing more harm than purported safety interests.

● Practical lessons, knowledge, and tools to advocate for

and organize around removing jaywalking laws and

enforcement in your community.

● Intimate and timely strategies straight from the

leaders/advocates who have recently worked to repeal

jaywalking laws in their region and those who are in the

thick of it.

● The nuances of considering place, authentic community