1

P

ENSION PROJECTIONS FOR THE

2021

A

GEING

R

EPORT

C

OUNTRY FICHE

F

RANCE

Final Version – March 2021

2

Table of contents

1. Overview of the pension system .................................................................................. 3

1.1. Description ........................................................................................................... 3

1.2. Recent reforms of the pension system included in the projections .................... 11

1.3. Description of the actual ‘constant policy’ assumptions used in the projection 15

2. Overview of the demographic and labour forces projections .................................... 16

2.1. Demographic development ................................................................................ 16

2.2. Labour force ....................................................................................................... 17

3.1. Extent of the coverage of the pension schemes in the projections ..................... 20

3.2. Overview of projection results ........................................................................... 21

3.3. Description of main driving forces behind the projection results and their

implications .......................................................................................................................... 25

3.4. Financing of the pension system ........................................................................ 35

3.5. Sensitivity analysis ............................................................................................. 37

3.6. Description of the changes in comparison with the 2006, 2009, 2012, 2015 and

2018 projections ................................................................................................................... 39

4. Description of the pension projection model and its base data ................................. 44

4.1. Institutional context in which the projections are made ..................................... 44

4.2. Data used to run the model ................................................................................. 44

4.3. General description of the model ....................................................................... 45

4.4. Assumptions and methodologies applied ........................................................... 46

4.5. Additional features of the projection model ....................................................... 47

5. Appendix ................................................................................................................... 48

A. Methodological annex ............................................................................................ 48

B. Retirement ages of the French pension system ...................................................... 53

C. Full pension contribution period ............................................................................ 54

E. Projected and disaggregated new public pension expenditure (old-age and early

earnings-related pensions) .................................................................................................... 58

F. Overview of the sensitivity tests ............................................................................ 60

G. Panorama of the main pension schemes ................................................................ 62

6. References ................................................................................................................. 64

3

1. Overview of the pension system

1.1. Description

- A system made of different schemes for old-age and survivor pensions

The French pension system is essentially a pay-as-you-go system financed by contributions from both

workers and employers. The description of the pension system and the projections are based on the

legislation in force in 2020.

The French pension system is based on several schemes depending on the professional sector or

occupational status. The private sector employees scheme (CNAV) is the largest one. These schemes

follow different rules. All workers are affiliated, according to their profession, at the same time to a

basic and a mandatory complementary scheme. They can belong to several basic schemes during their

career: they then receive several pensions at retirement.

Table 1.1 - Outline of the French pension system

4

Note: Regarding acronym developments, please refer to the glossary.

*Self-employed workers (artisans and retailers), affiliated to the Social Regime for the Self-Employed (Régime Social des Indépendants - RSI) until December 31, 2017, are affiliated to the Social

Security for the Self-Employed (Sécurité Sociale des Indépendants - SSI) from January 1, 2018, whose management is gradually assumed by the French National Old Age Insurance Fund (Caisse

Nationale d'Assurance Vieillesse - CNAV).

5

Special Schemes

Within the special pension schemes, there are three families:

• The special civil service scheme (civil and military servants) ;

• The regime for companies and public establishments ;

• Other schemes grouped around a profession or company.

The main special schemes include :

• The scheme for civil servants, magistrates and military personnel covered by the Civil and Mil-

itary Retirement Pensions Code ;

• The SNCF's scheme with the SNCF provident and pension fund ;

• The scheme for Clerks and Notary Employees with the Pension and Welfare Fund for Clerks

and Notary Employees ;

• The RATP's scheme with the RATP staff pension fund ;

• The Seamen's regime with the National Establishment for the Invalids of the Navy ;

• The EDF-GDF Electricity and Gas Industries scheme with the National Fund for Electricity and

Gas Industries ;

• The Cult Plan with the Old Age and Illness Insurance Fund for Religious Leaders ;

• The Senate's parliamentary system with the Senate's autonomous social security fund, which

has not been aligned with the civil service system ;

• The parliamentary regime of the National Assembly with the Social Security Fund of the Na-

tional Assembly, aligned since January 2018 with the Civil Service regime ;

• The regime of the French Comedy ;

• The regime of the Autonomous Port of Strasbourg ;

• The Banque de France regime.

Special schemes represent about 4.5 million pensioners, i.e. 25.7% of French pensioners and 4.7 million

contributors, i.e. 3.4% of the labour force.

Special schemes workforce Contributors pensioners

Civil and military servants

2 058 000 2 355 000

Territorial and medical civil servants

2 223 000 1 155 000

Sate-owned industrial civil servants

35 772 103 682

Electricity and gas industries

146 103 164 895

SNCF

142 943 261 033

RATP

42 483 44 316

Clerks and Notary Employees

47 618 73 090

Seamen's

20 045 117 830

Banque de France

12 029 14 891

The mining regime

3 401 303 970

Paris National Opera

1 825 1 999

French Comedy

350 401

6

Retirement age

The retirement age depends on the behaviour of the new pensioners. There is a legal minimum age

1

and

incentives to retire later.

- People can retire when they reach the earliest retirement age (62 for the 1955 generation and

the following ones), with a penalty if they do not meet the required contribution period condition

(43 years from the 1973 generation onward).

- They can also delay their entry into retirement in order to obtain a full pension which is granted

for people with the required contribution period or above the statutory retirement age (also

called full pension age, 65 up to the 1951 generation, 67 for generations born in 1955 and after).

People who are allowed to retire with a full pension (as they meet the age and contribution

period conditions) but who decide to keep working will receive a bonus on their pension pro-

portional to the number of extra years worked.

There are some exceptions to the legal retirement age. The most important one is dedicated to people

who have started working at a very young age and have validated more than the required time (see

details infra). In the public sector, for some special branches among “active service” (policemen, nurses,

etc.), the minimum retirement age is 57 years old

2

. In general, there is no gender difference in the

eligibility requirements.

Table 1.2 – Qualifying conditions for retirement

20

20

20

3

0

20

4

0

20

5

0

20

6

0

20

7

0

20 contribution years *

statutory retirement age ** 67,0 67,0 67,0 67,0 67,0 67,0

earliest retirement age 62,0 62,0 62,0 62,0 62,0 62,0

penalty in case of earliest retirement age

25,0% 25,0% 25,0% 25,0% 25,0%

25,0%

bonus in case of late retirement *** 0,0% 0,0% 0,0% 0,0% 0,0% 0,0%

40 contribution years *

statutory retirement age ** 63,8 64,5 65,0 65,0 65,0 65,0

earliest retirement age 62,0 62,0 62,0 62,0 62,0 62,0

penalty in case of earliest retirement age

8,8% 12,5% 15,0% 15,0% 15,0%

15,0%

bonus in case of late retirement *** 16,3% 12,5% 10,0% 10,0% 10,0%

10,0%

* We assume that people have accumulated 20 or 40 years of contribution at their earliest retirement age the given year.

Statutory retirement age is then reached after that year.

** Statutory retirement age is reached when full pension is attain via contribution period or legal retirement age

*** We assume late retirement to be the legal automatic full rate pension age (67 yo. in 2020 and after)

NB: we do not distinguish between women and men since they face the same legislation.

Benefit fomula

a. Old age pension

The rules to calculate pensions differ from one scheme to another. We present here only the formula

used to calculate the two components of the pension in the private sector (basic pension from the CNAV

and complementary pension from the AGIRC-ARRCO) and in the public sector.

1

Rules may differ from the general situation in certain schemes, for instance, the complementary scheme of

independent professions.

2

Since the 2014 reform, the minimum retirement age for “active service” is increased from 55 years old for generation 1956

and before, to 57 years old for generation 1960 and after.

7

Basic private sector pensions (CNAV and aligned schemes)

In the basic private sector (CNAV) and the aligned schemes (RSI and MSA workers), the pension P is

calculated according to the following formula:

P=ref.wage ×Min (1,

D

T

)×t

Three factors compose that formula:

The reference wage is the average wage over the 25 best wages (up to the social security

ceiling, € 3 428 per month in 2020), with past earnings valorized in line with price inflation.

The coefficient of proratisation Min (1,D/T) with D being the contribution period, that is the

number of years validated by the insured and T, the reference length. In other words, the

pension is reduced in due proportion whenever D < T. For people born in 1959 (who will be

62 in 2021), T equals 41.75 years, this value will increase up to 43 years for people born in

1973 or after.

The pension rate t. The standard rate is 50%.

However, in order to foster senior participation rate in the labor market, either a penalty or a bonus can

be applied under certain conditions:

• A penalty is applied to the pension rate when the pension is withdrawn before the full pension age

if the contribution period is lower than the reference one (D < T). The deduction is then calculated

as Min [Full pension age - Age, (T-D)] multiplied by the rate of deduction (1.25% per missing

quarter from the 1953 cohort onward). The new pension rate t’ is given by:

= × (1 − 1.25% × number of missing quarters)

• Conversely, the pension is augmented by a premium when individuals decided to continue to work

although they had met the conditions for a full pension. The premium is calculated as

Min [Age - Minimum retirement age, (D-T)] multiplied by the premium rate (1.25% per quarter).

The new pension P’ is given by:

′ = × (1 + 1.25% × number of extra quarters worked)

There is a minimum contributory pension (named minimum contributif) for individuals who meet the

requirements for a full pension (ie. they are 67 years old or they have contributed long enough for being

granted a full pension before the age of 67) amounting to € 642,93

3

per month in January 2020. This

minimum is price-indexed.

Mandatory complementary pension (AGIRC-ARRCO for all private sector workers)

Complementary schemes for private sector employees are pay-as-you-go point systems that serve

defined-contribution pensions. Contributors acquire each year a certain number of points through their

own contributions and those of their employer, calculated on the basis of an acquisition rate τ

t

applied

to a part of their gross wage. The acquisition rate τ

t

equals the contribution rate of the scheme divided

by 127%. The purchase price of each point, called “reference wage”, depends on the year considered.

In January 2020, it amounted to € 17,3982.

Number of points acquired in year t = τ

t

× (Gross wage

t

/Purchase price of a point

t

)

3

Only individuals whose total pension (basic + complementary) does not exceed € 1 191,57 per month (in 2020)

are entitled to the minimum contributory pension of the basic scheme. A higher minimum contributif also exists

for people having contributed 120 quarters.

8

At retirement, the transformation of accumulated points into a pension benefit is a function of the

contributor's age, the contribution length and the selling price of a point at that date. Complementary

pension is then calculated as follows:

Pension = Total number of points acquired × Value of a point × Shortfall coefficient

“Full” complementary pension is granted only to those who qualify for a full basic scheme pension. In

case one retires before fulfilling the requirements for a full pension as defined by the CNAV, the value

of the point is adjusted downwards by means of a “shortfall coefficient” (cf. Table 2.2). For example, a

pensioner with 4, 12 or 20 contribution quarters missing will see his pension pro-rated by 0.96, 0.88 or

0.78 respectively.

Following the 2015 agreement (cf. 1.2), a new system of “solidarity coefficients” and “increase

coefficients” is factored into the calculation of the complementary pension benefit and is based on the

age at which employees acquire full rights to the basic pension under the CNAV general scheme will be

put in place, starting with the generation 1957. The coefficients work in the following way:

• For individuals who retire less than one calendar year after the age at which they are entitled to

a full basic pension, the AGIRC and ARRCO complementary pension benefits are reduced by

a solidarity coefficient of 10% for three years or until they turn 67.

• Individuals who retire between one and two years after that age receive their full pension, with

no solidarity coefficient or increase coefficient.

• For each additional year that the individual delays retirement, the AGIRC and ARRCO comple-

mentary pension is increased for one year by an increase coefficient of 10% (up to a maximum

30%).

• Pensioners exempted from the “general social security contribution” (Contribution Sociale Gé-

néralisée: CSG) and certain precarious categories of pensioners

4

are exempted from the solidar-

ity coefficient (but are subject to the increase coefficient). Pensioners paying the CSG at the

reduced rate

5

are subject to the solidarity coefficient but with a 5% reduction instead of 10%.

Pension in the public service scheme (FPE)

The calculation of the basic pension for public sector workers is very similar to the one in the CNAV:

P=ref.wage×Min (1,

D

T

)×t

Nevertheless the parameters differ from those of the general scheme in two essential aspects:

• The reference wage taken into account is the wage received the last 6 months (excluding

bonuses and other emoluments), as opposed to the average of the best 25 years' wages (including

bonuses) in the private sector.

• The pension rate t is 75%. The 2003 reform introduced also a penalty scheme and a premium

rate, similar to the ones existing for private sector employees.

As in the main basic scheme, the duration T taken into account in the pro rata coefficient is 41.75 years

for people born in 1959 (aged 62 in 2021) and will increase up to 43 years for people born in 1973 and

after.

4

The 30 October 2015 agreement lists the conditions for exemption from solidarity coefficients.

5

The standard CSG rate for pensioners is 6.6%. The reduced CSG rate (3.8%) and exemption from CSG are

subject to means testing.

9

Unlike private sector employees, public sector employees did not receive complementary pensions until

recently. This is why their basic scheme replacement rate is higher. A complementary pension scheme

(RAFP) was introduced in 2005 by the 2003 reform. It is a point system whose contributions are only

based on bonuses, within the limit of 20% of total wage. This scheme provides pensions which are much

lower than those of the private sector complementary schemes.

For pensioners who meet the requirements for a full pension, an earnings-related minimum pension is

guaranteed (called minimum garanti). In 2020, its value was € 14 092,08 per year (€ 1 174,34 monthly)

for a 40 year long career.

b. Survivor pension

The surviving spouse's allowances include the survivor's pension (pension de réversion), which corre-

sponds to a proportion of the pension which the deceased person could have received and which it is

paid to the surviving spouse or ex-spouse and the widowhood allowance (allocation de veuvage), which

is paid to the surviving spouse depending on her income if she does not meet the conditions of age in

order to benefit from a survivor's pension. The survivor's pension

may be granted, even if the deceased

spouse died before retirement or before reaching the minimum retirement age.

Basic private sector survivor pensions (CNAV and aligned schemes)

To benefit from the survivor pension, the surviving spouse or ex-spouse:

• must have been a married to the deceased beneficiary (the Pacs civil partnership and cohabita-

tion do not entitle the partner to the survivor's pension);

• must be at least 55 years old, this age being reduced in certain cases (death or disappearance

before 2009);

• must earn gross annual income that does not exceed €21,112 if she lives alone, or €33,779.20 if

she lives with a partner.

If the deceased spouse has been married several times, the survivor pension is shared between the sur-

viving spouse and the divorced ex-spouse(s). This division is proportional to the duration of each mar-

riage.

The survivors pension is equal to 54% of the deceased spouse or ex-spouse’s basic pension (or the basic

pension she could have benefited from). If the spouse or ex-spouse made 15 years of contributions to

the general pension scheme, the minimum amount of your survivor's pension is €3,478.46 per year in

2020. If the deceased had contributed for less than 15 years, this minimum total is reduced proportion-

ally. In 2020, the amount of the survivor's pension cannot exceed €11,106.72 per year.

Pension in the public service scheme (FPE)

To benefit from the survivor pension, the surviving spouse or ex-spouse of a public servant must qualify

for at least one of the following conditions:

• to have been married to the deceased beneficiary at least four years

• to have been married to the deceased beneficiary at least two years before the deceased spouse

retired;

• to have at least one child with the deceased beneficiary

To benefit from the survivor pension, the surviving spouse must not live with a partner.

10

The survivor pension is equal to 50% of the deceased spouse or ex-spouse’ pension (or the pension she

could have benefited from). It can be increased by half of the majoration the deceased spouse benefited

for having raised at least three children.

c. Non earnings-related minimum pension

People aged 65 and above (or 62 in case of incapacity or disability) whose revenues (including pension

or not) are below a certain ceiling (€ 10 838,40 a year for a single person and € 16 826,64 for a couple

in 2020) are eligible to a minimum pension, named ASPA (standing for “Allocation de solidarité aux

personnes âgées”) that tops revenues up to the aforementioned ceiling. ASPA-related expenditures

amounted to € 3,1 billion in 2018, which represents 1 % of the total amount of pension expenditures.

d. Disability pension

Disability pensions provide a replacement income for people who are completely or partially,

temporarily or permanently, unable to work. These pensions are paid by the public health insurance

schemes.

There are two different earnings-related disability pensions: the “rente Accident du Travail et Maladie

Professionnelle (ATMP)” which is granted when the disability is related to work and the “Pension

d’Invalidité (PI)” which is granted when it is not work-related. When disabled persons receiving a PI

reach the legal retirement age, they become eligible to a full pension replacing their disability pension:

their pension is no longer included in disability expenditures and is transferred into old-age

expenditures’ accounts. This is also true for PI for public servants even if in practice they receive an

only pension before and after legal retirement age. On the contrary, the ATMP pension is perceived is

cumulative with an old-age pension.

These earnings-related disability pensions are a fraction of a reference wage (the average of the ten best

wages for PI and twelve last months for ATMP), depending on the disability level as exhibited in the

following table. It cannot exceed a maximum nor be inferior to a minimum amount.

• for PI calculation, the percentage applied to the reference wage varies according to the disability

class (1st class, 2

nd

class or 3rd class), from 30% (1st class) to 50% class (2

nd

class, with an

additional 40% bonus for a third party for 3rd class); minimum and maximum level also vary

from respectively 292.80€ (1st class and 2

nd

class) per month to 1,418.09€ (3rd class) and from

1,028.40€ (1st class) to 1,714.00€ (2

nd

class) to 2,839.29€ (3rd class)

6

.

• concerning ATMP, the annuel pension (P) equals : P = T x R, with :

= 0.5 × if disability rate ≤ 50%

= 1.5 × – 50% if disability rate > 50%

= ref.wage if ref.wage ≤ °

= ° +

.°

if < ref.wage ≤4°

with R° = € 37,262.59. Revenues above 4R° are not factored into the calculation.

A non earnings-related minimum disability pension (“Allocation aux adultes handicapés” - AAH) is

also considered in the projections : AAH tops revenue of all disabled people up to a ceiling of € 902.70

per month in 2020. Howener, in the absence of a detailed breakdown of recipients and expenditures by

profile, expenses related to Allocation spécifique invalidité (ASI), another non earnings-related

minimum disability pension which accounts for less than 250 M€ in 2018, are not included.

6

Source : Public administration official website : www.service-public.fr.

11

Indexation

All basic schemes pensions, as well as disability pensions (PI, ATMP), are price-indexed. Past wages

taken into account for the pension calculation are also revalued with the Consumer Price Index

(excluding tobacco).

According to the latest agreement, complementary schemes’ pensions (AGIRC and ARRCO) are price-

indexed from 2019 to 2022, then indexed according to the evolution of the average wage affected by a

sustainability coefficient of - 1.16 % from 2023 onwards 2020.

Non earnings-related minimum pensions (ASPA and AAH) are also price-indexed.

Taxation

Pensions are subject to the General Social Contribution (CSG) at a rate of 8.3%, the Social Debt

Repayment Contribution (CRDS) at a rate of 0.5% and to two different health contributions: a specific

contribution for all pensioners (Additional Solidarity Contribution for Autonomy - Casa) at a rate of

0.3% and a 1% health insurance contribution withholding which is applied to both compulsory and non-

compulsory supplementary pension schemes.

Pensioners can benefit from a reduced rate of 3.8% of CSG if their income is below a certain ceiling

(€14,780 for a single tax unit in 2020 – calculated on the reference taxable income for 2018) or an

intermediate rate of 6.6% if their reference taxable income is between €14,781 and €22,940 in 2018 for

a single tax unit. They can also benefit from an exemption of CSG and CRDS if their income is below

a certain ceiling (€11,306 for a single tax unit in 2020 – calculated on the reference taxable income for

2018). Also, the Additional Solidarity Contribution for Autonomy of 0.3% is only levied for pensioners

subject to a CSG rate of 6.6% or 8.3%.

Pensions are also subject to income taxation (after a 10% rebate on the tax base). All in all, the average

tax rate in 2019 was 13.3%: 6.4% for income taxation and 6.9% for other taxes (CSG-CRDS-Casa).

There is no taxation (CSG, CRDS, Casa,income taxation) on ATMP pensions nor non earnings-related

minimum pensions (AAH, ASPA).

1.2. Recent reforms of the pension system included in the projections

Up to the last projection exercice, the French pension schemes have known five main reforms: the 1993

reform in the private sector, the 2003, 2008, 2010 and 2014 reforms that affect both private and public

sectors. Regarding the Ageing Report 2021 projections, the 2015 reform affects the AGIRC-ARRCO

schemes, thus the private sector. In addition, the reforms from 2017 to 2019 had a less significant impact

on the French pension system.

The 1993 reform introduced mainly four changes that reduced the pension level:

- The reference wage is now calculated on the basis of the 25 best wages instead of the 10 best

ones;

- Past wages factored into the calculation of the reference wage are price-indexed (and not wage-

indexed anymore);

- Pensions have become price-indexed;

- The reference contribution period has been raised from 37.5 to 40 years for private sector

employees.

12

The 2003 reform:

- It planned to semi-automatically increase the contribution period necessary to draw a full

pension in line with life expectancy gains. The aim was to keep the ratio between contribution

period and average length in retirement constant at its value of 2003 (1.79)

7

. In application of

that principle, the reference contribution period has increased from 40 years for generation 1948

to 41.5 years for generation 1957. This mechanism has been replaced by the 2014 reform.

- It created the possibility for people with long careers to retire early and scheduled an increase

of the minimum earnings-related pension. The early retirement arrangement for long careers

concerns people who started to work before the age of 16 or 20 and who have contributed longer

than the reference contribution period. They are entitled to withdraw their pension up to 4 years

before the legal retirement age (56 years old). With the legal obligation to study until the age of

16, fewer and fewer people will be eligible to this arrangement.

- A bonus system was introduced (in all schemes) for people postponing their entry into

retirement while they have reached the minimum retirement age and they meet the reference

contribution period condition. The penalty for early-retirement was gradually decreased from

10% to 5% of pension benefits for private sector workers and was introduced for the public

scheme. The reform also introduced the possibility of cumulating a pension and a wage and

fostered the development of occupational and voluntary private savings through fiscal

incentives.

- A gradual convergence of the public sector schemes toward the private sector one was

implemented through three channels: firstly, an increase of the number of contribution years

required for entitlement to a full pension (from 37.5 to 40 years); secondly, the creation of a

penalty for early retirement and a premium for postponed retirement converging gradually to

the value of the parameters in the CNAV; finally, the creation of a complementary scheme

(RAFP).

The 2008 “rendez-vous”:

- The bonus for extra years worked after having reached the required contribution period for a

full pension was raised to 1.25% per additional quarter;

- The possibility of drawing concurrently a pension and a wage was fully liberalized for people

entitled to a full pension;

- Employers were encouraged to reach quantitative targets for senior workers’ employment and

discouraged to use retirement as a substitute for layoff.

- The conditions for perceiving the Minimum Contributif (also called Mico), a contributory

minimum pension created for people entitled to a full pension, were strengthened. This

minimum pension is now means-tested in order to target people with low levels of pension more

effectively.

7

Average length in retirement is defined as the life expectancy at age 60 published five years before by the national

statistical agency (Insee). Until 2014, the COR pronounced every year (every 4 years before) a recommendation

concerning the reference contribution period that will apply to the concerned generation: everyone is therefore

informed at age 55 of the actual reference contribution length that will apply to them.

13

The 2010 reform introduced several new measures aimed at both curbing expenditures and raising

revenues:

- It introduced a progressive rise of age boundaries. The earliest retirement age was gradually

increased, for all pension schemes, from 60 to 62. Simultaneously, the full pension age went up

from 65 to 67. Every generation from generation 1951 to generation 1955 have seen these age

limits rise by 4 or 5 months

8

. For example, people born in 1956 can claim their pension at age

62 in 2018 and a full pension at 67 in 2023. The early retirement age for long careers has also

been increased by 2 years. The 2010 reform, so as the 2008 “rendez-vous” increased the

minimum contribution period required for a full pension before the age of 67.

- Exceptions related to fragile workers have been introduced. Some categories of workers are still

being granted a full pension at 65 (disabled, mother of 3 children), and people suffering from a

professional disease or an accident that resulted in a permanent incapacity of at least 20%

9

can

still retire at 60 with a full pension. The retirement for long careers is extended to people who

started to work before 18; they can retire at age 60, if they meet certain conditions.

- The convergence of pension rules between public and private sectors was strengthened by the

decision to remove the possibility of early retirement for parents with 3 children and a 15 year-

career in the public sector and the "Cessation Progressive d'Activité" programme in the public

sector as well. Rules to compute minimum earnings-related pensions and the contribution rate

of civil servants

10

will also converge towards the private sector rules.

The 2014 reform introduced short-term measures (increase of social contributions of both employ-

ees and firms by 0.3 point between 2013 and 2017, removal of the 10 % tax exemption on the pen-

sion bonus for pensioners with 3 (or more) children, postponement of the pension indexation) but

also several long-term measures:

- It introduced a progressive rise of the reference contribution period for a full pension before the

age of 67 to 43 years (reached in 2035). This rule replaces the mechanism introduced by the

2010 reform and affect all pension schemes (basic private sector schemes, the public sector

scheme, special schemes and 2nd pillar schemes);

- In order to strengthen the governance, a steering committee has been established and has been

entrusted with the task to publish a yearly report on the French pension system, including long-

term projections. It will make recommendations if there are significant discrepancies with the

baseline scenario.

The 30 October 2015 agreement on complementary pension schemes AGIRC and ARRCO intro-

duced a series of measures related to: (i) the amount of pension benefits paid to retirees, (ii) retire-

ment age, with incentives to postpone retirement, (iii) governance, with the merger of the executive

and non-executive schemes, and (iv) social contributions.

- The measures concerning the amount of pension benefits are being implemented from 2016 to

2018; part of the adjustment affects current pension recipients by restricting nominal increases

8

Initially, a 4 month increase by generation was planned between the generations 1951 and 1956 but the 2012

social security budget law planned an acceleration of this increase.

9

10% under specific disability conditions.

10

The contribution rate for civil servants will increase from 7.85% to 11.10% by 2020. It amounted to 10.29% in

2017.

14

in existing pensions, and part will affect future pensioners by making the pension system less

generous in the long run.

- Incentives to remain in employment (“solidarity coefficients” and “increase coefficients”)

should raise the effective retirement age and maintain around 100,000 additional persons in the

labour force in 2025, thus raising the amount of contributions.

- Merging the AGIRC (executive) and ARRCO (non-executive) schemes in 2019 will simplify

the pension system and reduce administrative costs.

- In the new unified scheme, the contribution assessment base will be broadened and certain

contribution rates will be increased.

In July 2017, the LURA reform (LURA stands for Liquidation Unique de retraite de base des Ré-

gimes Alignés) entered into force. Before the reform, private sector workers who had contributed to

several basic schemes over their career (CNAV, MSA salaries or SSI) used to receive as many

pensions as schemes they had contributed to and each pension was calculated separately. Since July

2017, individuals who are in such a situation

11

receive only one pension calculated according to one

single benefit formula.

- The reference wage is the average of the 25 best annual wages (valorized in line with inflation)

across the entire career.

- An individual can only validate 4 quarters per year: individuals who have contributed to two

schemes simultaneaously will get a lower pension than what they would have received before

the LURA reform.

The LURA arrangement was part of the 2014 reform but the executive order related to its

implementation was published only in May 2017.

The following reforms are new to Ageing report 2021 projections :

In May 2019, the evolution of the AGIRC-ARRCO purchase and service value of the point, decided

aims to maintain the financial balance of the scheme over a multi-year horizon.Two periods are

distinguished: from 2019 to 2022 included, the service value of the point is indexed to the projected

inflation excluding tobacco prices and without the possibility of a negative indexation; the purchase

value is indexed to the yearly average gross wage. From 2023 to 2030, the service value of the point

is indexed to the yearly average gross wage minus a sustainability coefficient equal to -1.16%, and

the purchase value to the average gross wage.

In addition, from 2018 to 2020, increases in non earnings-related minimum pensions have been

introduced : the solidarity allowance for the elderly (ASPA) has increased from €803 in early 2018

to €903 by 2020 ; the adult disability allowance (AAH), standing at €819 in early 2018, amounts

€903 by 2020.

During his presidential campaign, the President announced that he will reform the pension system in

order to unify the 42 existing schemes into a single scheme, making the French pension system more

clear and fair. This reform was under discussion in parliament before being stopped by the Covid-19

health crisis.

11

The reform does not affect individuals who had already retired before July 2017

15

1.3. Description of the actual ‘constant policy’ assumptions used in the

projection

The projections are built upon a “constant policy” principle and based on the legislation and rules as of

September 2017. As described above, the rates of return of the AGIRC-ARRCO schemes are assumed

to remain constant after the last measures of the 2015 agreement are implemented, in 2018.

In order to prevent the minimum pension expenditures (ASPA and AAH) to decline too much in the

projection exercice relatively to the poverty threshold, the ASPA and AAH ceilings are indexed on

average wages when they account for less than 50 % of the poverty threshold

12

(60% of the median

wage). The impact of this methodological change on the projection results is shown in Table 19 in

section 3.6.

The two earnings-related disability pensions (ATMP pension and PI) are wage-indexed in the

projections, as their amount mainly depend on past wages taken into account for the pensions

calculation

13

.

12

In the projection exercice, the poverty threshold is deemed to evolve practically in the same way as average wage.

13

This assumption leads to overestimate the disability pensions in the projections, since pensions that have already been

provided in a previous year are revalued with the Consumer Price Index (excluding tobacco).

16

2. Overview of the demographic and labour forces projections

2.1. Demographic development

Table 2 – Main demographic variables

2019 2030 2040 2050

2060

2070

peak

va-

lue

peak

year

chang

e

2019-

2070

Population (thousand) 67 105 68 814 69

834

70

001

69

662

69 426 7003

4,1

2047

2320,7

Population growth rate 0,2 0,2 0,1 0,0 -0,1 0,0 0,3 2020

-0,2

Old-age dependency ratio (pop 65+ / pop 20-64)

36,5 44,9 51,7 54,8 55,9 56,9 56,9 2070

20,4

Old-age dependency ratio (pop 75+ / pop 20-74)

14,2 19,4 23,8 26,9 28,0 28,7 28,8 2067

14,5

Ageing of the aged (pop 80+ / pop 65+) 30,3 32,1 36,8 40,5 42,2 43,9 43,9 2070

13,5

Men - Life expectancy at birth 80,1 81,6 83,0 84,3 85,6 86,7 86,7 2070

6,6

Women - Life expectancy at birth 86,3 87,4 88,6 89,6 90,6 91,4 91,4 2069

5,1

Men - Life expectancy at 65 20,0 20,9 21,8 22,6 23,5 24,2 24,2 2069

4,2

Women - Life expectancy at 65 24,1 24,9 25,7 26,5 27,2 27,9 27,9 2070

3,8

Men - Survivor rate at 65+ 85,9 88,2 90,0 91,5 92,7 93,8 93,8 2070

7,9

Women - Survivor rate at 65+ 92,9 94,0 94,9 95,6 96,2 96,7 96,7 2070

3,8

Men - Survivor rate at 80+ 62,1 67,1 71,1 74,8 78,0 80,9 80,9 2070

18,7

Women - Survivor rate at 80+ 79,3 82,3 84,6 86,7 88,5 90,0 90,0 2070

10,8

Net migration (thousand) 38,1 68,3 73,9 75,2 74,6 80,2 80,4 2024

42,1

Net migration over population change 0,3 0,5 1,1 -4,5 -1,9 -9,4 42,3 2047

-9,7

Source: Commission services based on Eurostat EUROPOP2018 data

Explanatory note: *This column represents a peak year, i.e. the year in which the particular variable reaches its maximum

over the projection period 2016 to 2070.

Table 2 provides an overview of the demographic development until 2070. The total size of the

population will increase until 2070 up to 69 million people, increasing until 2050 and slightly decreasing

thereafter. This global increase of the total population comes mainly from the increase in life

expectancies, mitigated by lower fertility rates in the second half of the period.

The age composition will change towards older people: the “old-age dependency” ratio which is the

share of older people (aged 65 and above) relative to the working age population (aged 20 to 64) will

increase from 36.5% in 2019 to 56.9% in 2070. Most of the increase in old-age dependency ratio will

occur before 2050: after this date, the ratio will sligthly increase because the increase in the number of

65+ people and the decrease in the numer of 20 to 64 people will be much lower. The “ageing of the

aged” ratio, which is defined by people older than 80 years old as a share of people aged 65 or above,

will first decrease until 2025, then increase the remainder of the projection period. Among the 65 years

old and older group, the age composition will thus change towards a higher share of the elderly (over

80).

17

Figure 1 – Age pyramid, comparison between 2019 and 2070

Source: Commission services based on Eurostat EUROPOP2018 data

The main differences between the age composition of the population in 2016 and 2070 are the following

ones:

- The share of people aged between 25 and 49 will be significantly lower in 2070 than in

2016.

- On the contrary, the share of people aged 69 and above will be higher in 2070 than in 2016.

Due to the dynamic fertility, the share of young people will still be high in 2070. As a whole, the age

pyramid would be flatter in 2070 than in 2016.

The comparisons between age pyramids in 2016 and 2070 are quite similar between men and women,

except that the share of the elderly will be even higher for women than for men in 2070.

2.2. Labour force

Pension reforms that shift retirement age (both early and statutory) or rise contribution period

requirements as well as active labour market policies aim to prolong working life.

43210

FR - Population by age groups and sex as a

share of total population

Males

01234

0-4

5-9

10-14

15-19

20-24

25-29

30-34

35-39

40-44

45-49

50-54

55-59

60-64

65-69

70-74

75-79

80-84

85-89

90+

Females

Age

groups

2070

2019

18

Table 3 – Participation rate, employment rate and share of workers for the age groups

20-64, 20-74, 55-64 and 65-74

2019 2030 2040 2050 2060 2070

peak

value

peak year

change

2019-

2070

Labour force participation

rate 20-64

78,0 78,8 79,7 80,0 80,1 80,0 80,2 2057 1,9

Employment rate of workers

aged 20-64

71,6 72,4 73,8 74,6 74,7 74,5 74,8 2057 2,9

Share of workers aged 20-

64 in the labour force 20-64

91,8 91,9 92,6 93,2 93,2 93,2 93,2 2057 1,5

Labour force participation

rate 20-74

66,2 66,5 67,2 68,2 68,3 68,2 68,5 2066 2,0

Employment rate of workers

aged 20-74

60,8 61,2 62,3 63,7 63,8 63,7 64,0 2066 2,9

Share of workers aged 20-

74 in the labour force 20-74

91,8 92,0 92,7 93,4 93,4 93,4 93,4 2055 1,6

Labour force participation

rate 55-64

56,9 62,9 65,8 66,4 67,3 67,0 67,3 2058 10,1

Employment rate of workers

aged 55-64

53,0 58,7 61,8 62,7 63,5 63,3 63,6 2058 10,2

Share of workers aged 55-

64 in the labour force 55-64

93,2 93,4 93,9 94,3 94,4 94,4 94,4 2065 1,2

Labour force participation

rate 65-74

5,5 9,1 11,8 14,4 14,0 14,6 14,7 2067 9,0

Employment rate of workers

aged 65-74

5,4 8,8 11,5 14,1 13,6 14,2 14,3 2067 8,8

Share of workers aged 65-

74 in the labour force 65-74

97,2 96,8 97,1 97,4 97,4 97,4 97,4 2059 0,2

Median age of the labour

force

41,0 41,0 41,0 41,0 42,0 41,0 42,0 2056 0,0

Source: Commission services

Explanatory note: *This column represents a peak year, i.e. the year in which the particular variable reaches its maximum

over the projection period 2019 to 2070.

The effects of these reforms in France are reflected in the increase of participation rate and employment

rate of the elderly (see Table 3). In line with the rise observed during the past 10 years, participation and

employment rates of the 55 to 64 years old will globally keep increasing until 2060: respectively from

56.9 % in 2019 to 67.3 % in 2060 for the participation rate, and 53.0 % to 63.6 % for the employment

rate.

Table 4a – Labour market exit age, effective retirement age and expected duration of

life spent in retirement – MEN

2020 2030 2040 2050 2060 2070

peak

value

peak

year

change

2020-2070

Average effective retirement age (admin-

istrative data)*

62,0

Average labour market exit age (CSM)** 62,3 63,6 64,5 64,7 64,7 64,7 64,7 2042 2,4

Contributory period 38,3 33,8 34,9 34,8 34,2 34,6 38,3 2020 -3,7

Duration of retirement*** 22,2 21,6 22,6 22,6 23,5 24,2 24,2 2069 2,0

Duration of retirement/contributory period

0,6 0,6 0,6 0,6 0,7 0,7 0,7 2069 0,1

Percentage of adult life spent in retire-

ment****

33,4 32,1 32,7 32,6 33,5 34,1 34,1 2069 0,8

Early/late exit***** 7,8 3,4 1,9 1,6 1,5 1,4 7,8 2020 -6,4

Source: Commission services; Insee, DESTINIE model, calculations: DG Trésor

19

Table 4b – Labour market exit age, effective retirement age and expected duration of

life spent in retirement – WOMEN

2020 2030 2040 2050 2060 2070

peak

value

peak

year

change

2020-2070

Average effective retirement age (ad-

ministrative data)*

62,6

Average labour market exit age (CSM)**

62,2 63,3 64,1 64,3 64,3 64,3 64,3 2041 2,1

Contributory period 32,4 28,8 31,0 30,7 31,6 31,1 32,4 2020 -1,2

Duration of retirement*** 26,7 26,7 26,6 27,4 28,1 28,8 28,8 2069 2,1

Duration of retirement/contributory pe-

riod

0,8 0,9 0,9 0,9 0,9 0,9 0,9 2025 0,1

Percentage of adult life spent in retire-

ment****

37,6 37,1 36,6 37,2 37,8 38,3 38,3 2069 0,7

Early/late exit***** 10,9 3,7 2,1 1,7 1,7 1,5 10,9 2020 -9,4

Source: Commission services; Insee, DESTINIE model, calculations: DG Trésor

Explanatory note: * The effective retirement age shows the age at which people on average start receiving a pension

benefit. It is calculated on the basis of the administrative data for 2019 (see Annex Tables A4a and A4b); ** The labour market

exit age as calculated based on Labour Force Survey data for the base year and estimated by the Cohort Simulation Model

thereafter; *** ‘Duration of retirement’ is calculated as the difference between the life expectancy at the average labour market

exit age and that exit age itself; **** The ‘percentage of adult life spent in retirement’ is calculated as the ratio between the

duration of retirement and the life expectancy minus 18 years; ***** Early/late exit is the ratio between those who retire and

are below the statutory retirement age and those who retire at the statutory retirement age or above.

The considerable diversity between the different schemes in terms of careers, particularly the age of

entry or demographics such as the share of women with the subject of the contribution quarters allocated

for maternity and child-rearing represent a limitation of the indicator presented in Table 4 for France.

Finally, differences in retirement age between schemes represent another limitation.

20

3. Pension projection results

3.1. Extent of the coverage of the pension schemes in the projections

The French projections cover all public pensions. Both basic and mandatory complementary schemes

have been taken into account. Given their low weight in the French pension system, occupational

pensions (with contractual agreements between employers and employees) are not covered in the

projections. Private mandatory pensions do not exist in France.

The projections cover old-age and early pensions as well as survivors’ pensions and the minimum old-

age allowance, called “ASPA” (formerly “minimum vieillesse”). They also cover disability pensions

paid before and after the minimum retirement age (including “pension d’invaliditié” (PI), allowance for

disabled adults (AAH), and “ATMP” pension for adults with a disability due to work and reducing their

capacity to work), even though they are part of health expenditures in the French accounting system.

People eligible to both ATMP pension and PI are identified from the administrative dataset of the Health

insurance schemes. Using aggregated data from the Ministry of Solidarity and Health, we estimate that

15 % of people eligible for AAH are also eligible for an ATMP pension or PI. Data on disability include

expenses and number of French people living abroad.

Table 5 - Eurostat (ESSPROS) vs. Ageing Working Group definition of pension

expenditure (% GDP)

2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

Change

2009-2019

1 Eurostat total pension

expenditure

14,3 14,4 14,5 14,8 15,1 15,1

15,1 15,1 14,9

2 Eurostat public pension

expenditure

3 Public pension expendi-

ture (AWG)

14,6 14,5

14,3 14,2 14,0 14,9

4 Difference (2) - (3)

5 Expenditure categories

not considered in the

AWG definition, please

specify:

5.1Early retirement

benefits

Source: Eurostat ESSPROS data (July 2017) and Social Protection Accounts, 2014 and 2018

Early retirement benefit values before 2011 are interpolated.

In this exercise like in the 2015 and 2018 ones, we strictly limit expenditures to pensions and take into

account disability pensions paid before and after the legal retirement age. Similarly to the 2018 exercise,

we include the allowance for adults with disability (AAH, 0.4% of GDP) in disability pensions, which

are not included by Eurostat and was previously in long-term care projections. This allowance was

shifted from long-term care to disability pensions due to changes in social protection accounts’

classifications.

21

Only a global projection of pension expenditures is provided in the projections, aggregating all

mandatory pension schemes for public, private and self-employed workers. The following table lists the

main pension schemes along with the amount of pensions distributed in 2018. No particular assumption

is made about the evolution of the respective shares of the different schemes.

Billion € 2018 % of GDP

CNAV

128,3 5,5 %

CNAVPL*

1,6 0,1 %

MSA employees

8,0 0,3 %

AGIRC-ARRCO

79,6 3,4 %

FPE

55,4 2,3 %

CNRACL

20,4 0,9 %

Special schemes

14

11,6 0,5 %

MSA farmers*

12,7 0,5 %

Source: Social Protection Accounts, Drees, 2020

*basic scheme only

3.2. Overview of projection results

Gross public pension spending is predicted to decrease from 14.8 % of GDP in 2019 to 12.6 % in 2070,

and peak in 2032 at 15.6 % of GDP, which represents an overall decrease of 2.2 GDP points over the

whole 2019-2070 period. Net public pension

15

spending is also predicted to decrease from 12.8 % of

GDP in 2019 to 10.9 in 2070, and peak in 2032 at 13.5 % of GDP which represents an overall decrease

of 1.9 GDP points over the whole 2019-2070 period (Table 6).

Pension contributions refer only to contributions that are collected on labour income, and not taxes on

pensions since they are not directly attributed to the financing of pension system. It must also be

highlighted that those contributions represent only a part of the global resources available: for old age

pensions, it represents around 80% of the global resources available in 2019; the remaining 20% is

collected through earmarked taxes, the FSV financial fund and taxes based on all the other types of

revenue (capital, replacement revenue…). Public pension contibutions are also predicted to decrease of

0.3 GDP points over the next five years but to remain stable around 11.5% of GDP until 2070.

14

SNCF, CRPCEN, CAVIMAC, ENIM, CANSSM, CNBF

15

Computed applying an average tax rate to the total gross public pensions.

22

Table 6 - Projected gross and net pension spending and contributions (% GDP)

Expenditure

2019 2030 2040 2050 2060 2070

Peak

value

Peak

year**

Change

2019-

2070

Gross public

pension

expenditures

14,8% 15,6% 15,2% 14,3% 13,4% 12,6%

16,2% 2020

-

2,2

Pivate

occupational

pensions

: : : : : :

:

:

Private

individual

mendatory

pensions

: : : : : :

:

:

Private

individual non

mendatory

pensions

: : : : : :

:

:

Gross total

pension

expenditures

14,8% 15,6% 15,2% 14,3% 13,4% 12,6%

16,2% 2020

-

2,2

Net public

pension

expenditures*

12,8% 13,5% 13,2% 12,4% 11,6% 10,9%

14,1% 2020

-

1,9

Net total

pensoin

expenditures*

12,8% 13,5% 13,2% 12,4% 11,6% 10,9%

14,1% 2020

-

1,9

Contributions

2019 2030 2040 2050 2060 2070

Peak

value

Peak

year**

Change

2019-

2070

Public pension

contributions

11,8% 11,5% 11,5% 11,5% 11,6% 11,6%

12,2%

2020

-

0,2

Total pension

contributions

11,8% 11,5% 11,5% 11,5% 11,6% 11,6%

12,2%

2020

-

0,2

Source: Commission services; Insee, DESTINIE model

Explanatory note: *net pension expenditure excludes taxes on pensions and compulsory social security contributions paid by

beneficiaries.**This column represents a peak year, i.e. the year in which the particular variable reaches its maximum over

the projection period 2019 to 2070.)

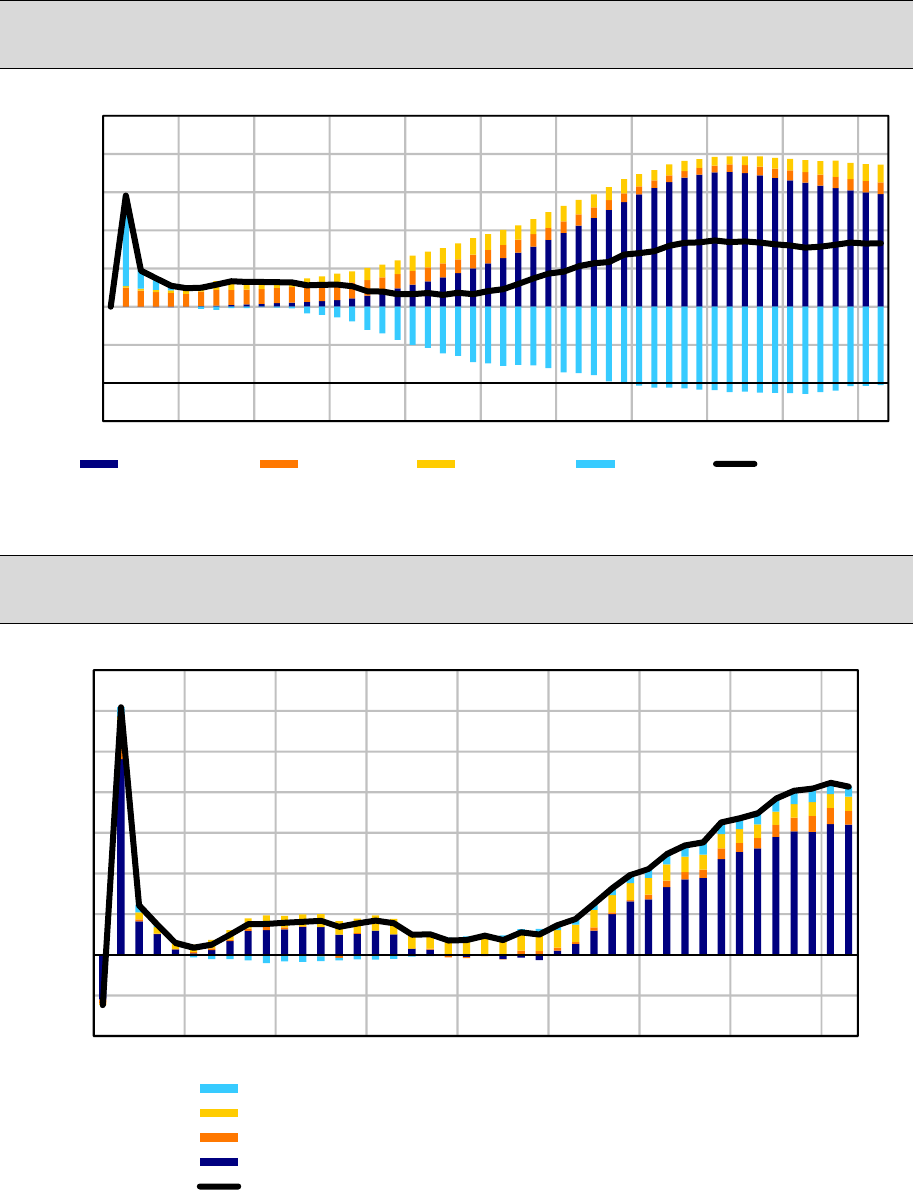

Concerning the 2019-2070 evolution of the ratio between projected gross pension expenditures and

GDP, six periods can be identified (Graph 2):

• Phase 1: Following the Covid-19 crisis, GDP was revised downwards which mechanically

increased the weight of pension expenditure to GDP. Up to 2021, pension expenditures as a

share of GDP will mainly reflect macroeconomic forecasts too.

• Phase 2: From 2021 to 2024, pension expenditures as a share of GDP will slightly decrease from

15.4% to 15.3% despite the ageing of the population due to the progressive increase of the

retirement age (past reforms).

• Phase 3: From 2025 to 2032, the ratio between pension expenditures and GDP will increase up

to 15.6% and then stagnate around this level until 2032. During this period, the number of

pensioners and the amount of new pensions is expected to continue raising at a sustained pace.

The ratio of pension expenditures to GDP is expected to decline continuously over the period 2033-2070,

to reach 12.5 % of GDP in 2070. This decline can be further broken down into three sub-periods:

23

• Phase 4: From 2033 to 2042, growth in pension expenditures will start showing signs of

deceleration which reflects the effect of the 2014 reform which consists in a progressive increase

of the minimum contribution period for a full rate pension.

• Phase 5: From 2043 to 2063, pension expenditures as a share of GDP are expected to decline

due to the slowdown of the ageing process which will prevent the number of people aged 65

and above and hence the number of retirees from growing. Strong nominal GDP growth relative

to growth in pension expenditures will also contribute to the sustained decline in the public

pension expenditure-to-GDP ratio.

• Phase 6: From 2063 to 2070, pension expenditures as a share of GDP will continue to decline

but at a slower pace as the growth rate of people aged 65 and above will accelerate and nominal

GDP growth will slightly decelerate.

Figure 2 - Projected pension expenditures (% of GDP)

Source: Insee, DESTINIE model, calculations: DG Trésor

11.0%

12.0%

13.0%

14.0%

15.0%

16.0%

17.0%

2019 2024 2029 2034 2039 2044 2049 2054 2059 2064 2069

Phase

2

Phase 3

Phase 4

Phase 5

Phase 6

Phase

1

24

Table 7 - Projected gross public pension spending by scheme (% GDP)

Pension scheme

2019 2030 2040 2050 2060 2070 Peak value Peak year *

Change

2019-2070

Total public pensions

14,8% 15,6% 15,2% 14,3% 13,4% 12,6%

16,2%

2020

-2,2

Old age and early pensions:

12,1% 13,1% 12,8% 12,1% 11,4% 10,7%

13,4%

2020

-1,4

Flat component

: : : : : :

:

:

:

Earnings related

12,0% 12,8% 12,5% 11,8% 11,1% 10,5%

13,1%

2020

-1,5

Minimum pensions (non-contribu-

tory) i.e. minimum income guarantee

for people above 65

0,2% 0,2% 0,3% 0,3% 0,2% 0,2%

0,3%

2040

0,1

Disability pensions

1,10% 1,08% 1,03% 0,97 % 0,95% 0,95%

1,2%

2020

-0,1

Survivor pensions

1,53% 1,46% 1,36% 1,18% 1,06% 0,94%

1,67%

2020

-0,6

Other pensions : : : : : : : : :

Source: Commission services; Insee, DESTINIE model

Note : Old age and early pensions include special sheme pensions

As old-age earnings-related pension expenditures represent the major share of total pension

expenditures, they follow the same evolution as described in 3.1.2. section : old-age earnings-related

pension spending (Table 7), as a share of GDP, would go down from 12.1 % of GDP in 2019 to 10.7 %

of GDP in 2070. By shifting the legal and statutory retirement ages, and increasing the minimum

contribution period, the 2014 reform contributed to reduce the weight of total pension expenditures in

GDP. Moreover, more fragmented careers and later entry into the labour market imply a lower average

amount of pensions as well as a lower average replacement rate at retirement.

The ratio between non earnings-related old-age pensions (“ASPA” or “minimum vieillesse”) and GDP

will first increase until 2037 and then slightly decrease to 0.2 % by 2070 (the impact of the change in

the indexation mechanism from 2063 onwards (wage instead of CPI indexation) is relatively small (cf.

Table 19).

Survivors’ pensions, as a share of GDP, are expected to decline from 1.1 % in 2019 to 1.0 % of GDP in

2070. The overwhelming majority of survivor pensions’ beneficiaries are women: the reduction of the

gap between life expectancies of men and women, the relative increase of women employment rates,

and the decrease of the number of weddings induce that women will have a lower and time-limited

amount of survivors’ pensions over the projection period.

Non-earnings-related minimum disability pension expenditures (AAH), as a share of GDP, are projected

to decline slightly until 2063 in the baseline scenario as AAH is price-indexed at first

16

.

16

The government has decided to increase the AAH (non-earnings-related disability pension) on an extraordinary basis in

November 2018 and November 2019 in order to bring the amount of the benefit to 900 euros by 2019 from 810,89 euros in

2017. -

25

3.3. Description of main driving forces behind the projection results

and their implications

In order to identify more clearly the driving forces behind the projection results, the pension-to-GDP

ratio is split into 4 factors:

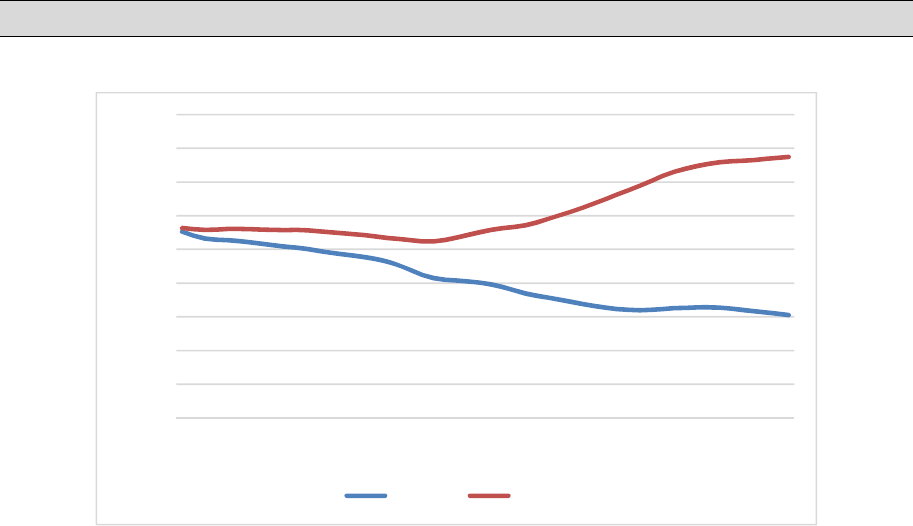

Figure 2 – Disaggregation of public pension expenditure

Figure 3 - Contribution of the main driving forces to the projection results

Source: Insee, D

ESTINIE model, calculations: DG Trésor

=

65+

20−64

×

65+

×

ℎ 20−74

×

20−64

ℎ 20−74

[

1

]

65+

=

65+

65+

+

≤65

50−64

×

50−64

65+

[2]

20−64

ℎ 20−74

=

20−64

20−64

×

20−64

ℎ 20−64

×

ℎ 20−64

ℎ 20−74

[3]

d

ependency rati

o

coverag

e

rati

o

l

abour market effec

t

benefi

t

rati

o

coverag

e

rati

o

ol

d

-ag

e

coverag

e

rati

o

earl

y

-ag

e

c

ohort effec

t

1/employment rat

e

1/labour intensit

y

1/career shif

t

-10%

-8%

-6%

-4%

-2%

0%

2%

4%

6%

8%

2019 2024 2029 2034 2039 2044 2049 2054 2059 2064 2069

Dependancy ratio Labour intensity Coverage ratio

Benefit ratio Public pensions to GDP

26

On the basis of the Eurostat demographic assumptions, the dependency ratio (population 65+/population

20-64) notably increases up to 2055 and then remains stable until 2070 (Figure 3). Concerning the

impact, ceteris paribus, of each of the factors considered on the evolution of pension expenditures (Table

8.a), the dependency ratio pushes up pension expenditures between 2019 and 2070 (+6.5 pp).

The coverage ratio (pensioners/population 65+) regularly decreases until 2040 and then stabilizes up to

2070. This is linked to the increase in retirement ages planned by the 2010 reform, but also to the increase

in the full pension contribution period planned by the 2014 reform which, associated with an increase

in the labour market entry age, leads to higher retirement ages. The coverage ratio mainly reduces public

pension expenditures as a share of GDP until 2040 (-1.3 pp).

The benefit ratio (defined as the average pension benefit divided by the economy-wide average wage)

declines all along the period (except in 2020), to reach in 2070 a level which is 66% lower than the

current level. The reduction of the benefit ratio reflects the subdued growth pace of the average pension

compared to that of the average wage per worker. First, the increase in discontinuous careers due to high

unemployment rates will not only decrease the average of the 25 best yearly wages (used to calculate

the pension) but also impact the prorata coefficient if individuals do not have the required number of

contributed years. Second, pensions are price-indexed while the average wage per worker increases in

line with labour productivity or GDP per worker, hence more rapidly. Finally, changes to the benefit

formulae induced by the last reforms will also contribute to the decline of the benefit ratio.

The labour market indicator (population aged 20 to 64/employed population aged 20 to 74) declines

over the first 30 years of the projection horizon and remains quite stable thereafter.

Table 8 - Factors behind the change in public pension expenditure between 2019 and

2070 (percentage points of GDP) – pensioners

S

2019-30 2030-40 2040-50

2050-

60

2060-

70

2019-

70

Public pensions to GDP

0,8 -0,4 -0,9 -0,9 -0,8 -2,2

Dependency ratio effect

3,4 2,3 0,9 0,3 0,2 7,1

Coverage ratio effect*

-1,1 -0,6 -0,1 -0,1 -0,1 -2,0

Coverage ratio old-age -0,1 -0,1 0,0 0,0 0,0 -0,2

Coverage ratio early-age -1,3 -1,7 0,0 -0,5 -0,2 -3,7

Cohort effect

-3,0 -2,2 -1,1 0,0 -0,1 -6,5

Benefit ratio effect

-1,0 -1,6 -1,4 -1,1 -0,9 -5,9

Labour market effect

-0,3 -0,4 -0,2 0,0 0,0 -1,0

Employment ratio effect -0,2 -0,3 -0,2 0,0 0,0 -0,6

Labour intensity effect 0,0 0,0 0,0 0,0 0,0 0,0

Career shift effect -0,2 -0,1 -0,1 0,0 0,0 -0,4

Residual

-0,2 -0,1 0,0 0,0 0,0 -0,4

Source: Commission services; Insee, DESTINIE model, calculations: DG Trésor

* Sub components of the coverage ratio effect do not add up necessarily.

The benefit ratio (BR - calculated as the average pension compared to the economy-wide average wage)

and the replacement rate (RR - calculated as the ratio between the average pension of new pensioners

and the average wage at retirement) will both decline during the projection horizon (Table 09). This

decline comes from several factors: the rise in the full pension contribution period, the rule used to

discount past wages entering into the benefit formula in interaction with an increase in the labour market

27

entry age and more fragmented careers, the development of polypension (when one pensioner cumulates

several pensions) that can imply smaller pensions because of the specific rules applied in this situation.

RR are usually calculated individually, by comparing the new pension at retirement with the last wage

at retirement

17

, and presented through the median replacement rate of the population. They are also often

calculated for theoretical or typical careers, for instance an entire career of a private sector employee

paid at the average wage. On the contrary in this exercise, RR are averaged over all careers and all

schemes; they are therefore smaller than the replacement rates exhibited in other reports, and should be

interpreted carefully. The BR, calculated by comparing pensions and wages of different generations, is

not a replacement rate: its evolution reflects the relative differences in the standards of living of the

workers and the pensioners.

Table 9 - Benefit ratio (BR), Replacement rate at retirement (RR) and Coverage by

pension scheme (in %)

2019 2030 2040 2050 2060 2070

change

2019-2070

(pps)

Public scheme (BR) 41% 39% 35% 32% 30% 28% -13%

Coverage 61,3 58,5 57,3 56,5 55,7 55,3 -6,0

Public scheme: old-age earnings re-

lated (BR)

52% 50% 45% 41% 38% 35% -17%

Public scheme: old-age earnings re-

lated (RR)

54% 50% 40% 42% 37% 35% -20%

Coverage 38,7 37,9 37,1 36,9 36,6 36,6 -2,1

Private occupational scheme (BR) : : : : : : :

Private occupational scheme (RR) : : : : : : :

Coverage : : : : : : :

Private individual schemes (BR) : : : : : : :

Private individual schemes (RR) : : : : : : :

Coverage : : : : : : :

Total benefit ratio : : : : : : :

Total replacement rate 0 0 0 0 0 0 0%

Source: Commission services ; Insee, DESTINIE model, calculations: DG Trésor

Explanatory note: Coverage of each pension scheme is calculated as a ratio of the number of pensioners within the scheme

and the total number of pensioners in the country.

Like in the 2018 exercise, there are two reasons why the number of pensioners is higher than the number

of people aged 65 and older (Table 10): on the one hand, some of the pensioners are younger than 65.

On the other hand, pensioners living abroad are included, while the demographic projections are limited

to the French territory

18

. In addition, pensioners living abroad are fewer in the 2021 projections than it

was in 2018.

The number of pensioners increases by 25% between 2019 and 2070, versus 0,3% only for the employed

population (Table 10). The growth of the number of pensioners is mostly concentrated before 2040, in

line with the demographic projections. This leads to an increase in the retired-to-employed population

17

Nonetheless, the definition of the replacement rate varies over the sources, and especially the definition of the

reference wage. There are many different publications which compare the new pension with the last full-time

wage, the average last 5 yearly wages, the wage at 50 years old, etc.

18

As a matter of fact, the sample of the population used to feed the Destinie model includes people living in France

only, but pensioners living abroad are included ex-post.

28

ratio between 2019 and 2070, with a stronger increase before 2040. The old-age dependency ratio

follows the same trend. The system efficiency ratio is expected to decrease over the projection period,

mainly due to the evolution of the old-age dependency ratio.

Table 10 – System Dependency Ratio and Old-age Dependency Ratio

2019 2030 2040 2050 2060 2070

change

2019-2070

Number of pensioners

(thousand) (I)

24079,9 27326,2 29694,4 30748,1 30925,9 30935,6

6855,7

Employment (thousand) (II)

27566,1 27869,4 28010,2 28016,8 27826,1 27641,2

75,1

Pension system depend-

ency ratio (SDR) (I)/(II)

87,4 98,1 106,0 109,7 111,1 111,9 24,6

Number of people aged

65+ (thousand) (III)

13611,4 16555,4 18680,9 19443,9 19724,0 19942,3

6331,0

Working age population 20-

64 (thousand) (IV)

37326,7 36906,3 36101,7 35510,6 35255,3 35050,7

-2275,9

Old-age dependency ratio

(OADR) (III)/(IV)

36,5 44,9 51,7 54,8 55,9 56,9 20,4

System efficiency

(SDR/OADR)

2,4 2,2 2,0 2,0 2,0 2,0 -0,4

Source: Commission services; Insee, DESTINIE model, calculations: DG Trésor

With regard to the age decomposition (Tables 11.a to 12.b), one should note that before the age of 60,

the ratio of pensioners to inactive population and total population is below 100% because there are few

possibilities to retire before 60. Around 90% of the pensioners younger than 54, and 70% of the

pensioners between 55 and 59 years old are disability pensioners. Conversely, this ratio is generally

above 100% for individuals aged 60 or above partly because inactive population is estimated on the

French territory while pensioners living abroad are still included in the projection (they account for

approximately 6% of total pensioners). Moreover, the computation of the pensioners-to-inactive

population and pensioners–to-total population ratios by age groups rely on two different data sources.

The number of pensioners by age groups is calculated based on national projections (old-age pensions

and disability pensions). Inactive and total population figures stem from labour force projections

obtained through the CSM method run by the Commission. Compared to the 2018 projection exercise,

there is a better match between CSM projection of the labour force exit age and the pension age projected

by the French microsimulation model (Graph 4.c). The pension age for men is slightly lower than the

labor market exit age calculated by the Commission. This is due to the early retirement scheme for long

careers which is not factored into the CSM calculation.

Figure 4c - Average labour market exit age (CSM) vs pension age (Destinie)

29

Source: Commission services, Insee Destinie model, calculation: DG Trésor

The pensioners-to-inactive population ratios by age groups are broadly stable over the projection period,

except for the age group 60-64. The ratio for the age group 60-64 declines by 20pp between 2016 and

2070. Although we should remain very cautious in the interpretation of this ratio and its evolution given

the aforementioned limitations, the evolution of the ratio likely reflects the effect of the 2010 and 2014

reforms that have increased the retirement age and the conditions for being granted a full rate pension.

Hence, a larger share of people aged between 60 and 64 is expected to be working in the coming decades.

This is also reflected by the evolution of the share of 60 to 64 year old pensioners among the total 60 to

64 year old population which is projected to sharply decrease over the projection horizon. The same

trend holds for women (Tables 13.a and 13.b).

The coverage ratio profiles also depend on retirement behaviour assumptions. But as the French pension

system is almost actuarially neutral at the margin, the impact of this assumption on public pension

expenditures is small (cf. annex E).

30

Table 11A – Pensioners (public schemes) to inactive population ratio by age group (%)

2019 2020 2030 2040 2050 2070

Age group -54 8,4 8,5 8,3 8,2 8,1 8,1

Age group 55-59 88,7 87,3 90,5 84,3 82,0 77,3

Age group 60-64 93,8 92,1 95,0 88,8 88,6 86,3

Age group 65-69 109,3 108,2 112,2 113,3 117,9 116,1

Age group 70-74 107,7 107,7 107,3 108,3 110,1 110,2

Age group 75+ 104,3 104,5 105,9 105,9 105,7 105,7

Source: Commission services; Insee, DESTINIE model, calculations: DG Trésor

Table 11B – Pensioners (public schemes) to population ratio by age group (%)

2019 2030 2040 2050 2060 2070

Age group -54 3,8 3,7 3,6 3,6 3,7 3,6

Age group 55-59 20,3 20,6 20,1 19,2 18,9 18,1

Age group 60-64 60,6 49,3 40,1 38,3 37,5 36,7

Age group 65-69 100,8 95,0 90,9 90,2 89,6 88,4

Age group 70-74 104,6 104,8 104,6 105,1 104,6 105,1

Age group 75+ 104,3 105,9 105,9 105,7 105,8 105,7

Source: Commission services; Insee, DESTINIE model, calculations: DG Trésor

Table 12A – Female pensioners (public schemes) to inactive population ratio by age

group (%)

2019 2030 2040 2050 2060 2070

Age group -54 8,0 7,9 7,8 7,7 7,8 7,4

Age group 55-59 83,7 84,9 80,5 79,6 76,6 72,6

Age group 60-64 92,6 92,6 91,4 90,3 90,5 89,2

Age group 65-69 106,0 107,9 111,6 115,3 116,4 115,9

Age group 70-74 105,9 106,8 108,1 110,0 108,4 110,6

Age group 75+ 104,1 105,7 105,6 105,4 105,6 105,2

Source: Commission services; Insee, D

ESTINIE model, calculations: DG Trésor

Table 12B – Female pensioners (public schemes) to total population ratio by age group

(%)

2019 2030 2040 2050 2060 2070

Age group -54 3,8 3,6 3,5 3,5 3,5 3,4

Age group 55-59 21,8 22,1 21,5 20,1 19,3 18,3

Age group 60-64 60,7 50,7 43,9 41,8 40,9 40,3

Age group 65-69 99,2 93,2 90,6 89,4 89,8 89,2

Age group 70-74 103,8 104,5 104,6 105,2 103,8 105,6

Age group 75+ 104,1 105,7 105,6 105,4 105,6 105,2

Source: Commission services; Insee, DESTINIE model, calculations: DG Trésor

The flow of new pension expenditures (public old-age earnings-related pensions for new pensioners)

can be broken down as the product of three terms: the average amount of new pensions, the number of

31

new pensioners

19

and the average number of months paid in the first year. The average amount of new

pensions can also be analyzed as the product of three terms (table 14.a)

20

:

1. the average contribution period of new pensioners ;

2. the value of pensionable earnings of new pensioners computed as the average of the present

value of the 25 best annual wages

21

;

3. the effective average accrual rate for new pensioners There is no administrative accrual rate

in the French legislation. Nevertheless, given the average amount of new pensions, the av-

erage contribution period among of new pensioners and the value of pensionable earnings

of new pensioners, it is possible to estimate ex-post “effective” accrual rates (see annex F).

There is no sustainability factor in the French pension system, therefore this factor remains constant

over the projection period.

The projected new pension expenditure is higher for men when compared to women (up to 24.6 M€ for

men vs. 20.1 M€ for women by 2070) even if women are more represented among new pensioners. This

is explained by the fact that women validate fewer quarters because of chopped careers and receive on

average lower salaries which impact negatively their average pension when compared to men.

Table 13a - Disaggregation of new public pension expenditure (old-age and early

earnings-related pensions) – Total

2019 2030 2040 2050 2060 2070