1

CushingCC, etal. BMJ Open 2019;9:e030029. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030029

Open access

Responsive Asthma Care for Teens

(ReACT): development protocol for an

adaptive mobile health intervention for

adolescents with asthma

Christopher C Cushing,

1

David A Fedele,

2

Susana R Patton,

3

Elizabeth L McQuaid,

4

Joshua M Smyth,

5

Sreekala Prabhakaran,

6

Selina Gierer,

7

Natalie Koskela-Staples,

6

Adrian Ortega,

1

Kandace K Fleming,

8

Arthur M Nezu

9

To cite: CushingCC, FedeleDA,

PattonSR, etal. Responsive

Asthma Care for Teens (ReACT):

development protocol for

an adaptive mobile health

intervention for adolescents

with asthma. BMJ Open

2019;9:e030029. doi:10.1136/

bmjopen-2019-030029

► Prepublication history for

this paper is available online.

To view these les, please visit

the journal online (http:// dx. doi.

org/ 10. 1136/ bmjopen- 2019-

030029).

DAF and CCC contributed

equally and the author order

was determined by a coin ip.

Received 25 February 2019

Revised 28 June 2019

Accepted 1 July 2019

For numbered afliations see

end of article.

Correspondence to

DrChristopher CCushing;

christopher. cushing@ ku. edu

Protocol

© Author(s) (or their

employer(s)) 2019. Re-use

permitted under CC BY-NC. No

commercial re-use. See rights

and permissions. Published by

BMJ.

ABSTRACT

Introduction Asthma is a leading cause of youth

morbidity in the USA, affecting >8% of youth. Adherence

to inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) can prevent asthma-

related morbidity; however, the typical adolescent with

asthma takes fewer than 50% of their prescribed doses.

Adolescents are uniquely vulnerable to suboptimal asthma

self-management due to still-developing executive

functioning capabilities that may impede consistent self-

regulation and weaken attempts to use problem solving to

overcome barriers to ICS adherence.

Methods and analysis The aims of this project are to

improve adherence to ICS as an important step towards

better self-management among adolescents aged 13–17

years diagnosed with asthma by merging the efcacious

behaviour change strategies found in behavioural health

interventions with scalable, adaptive mobile health

(mHealth) technologies to create the Responsive Asthma

Care for Teens programme (ReACT). ReACT intervention

content will be developed through an iterative user-centred

design process that includes conducting (1) one-on-one

interviews with 20 teens with asthma; (2) crowdsourced

feedback from a nationally representative panel of 100

adolescents with asthma and (3) an advisory board of

youth with asthma, a paediatric pulmonologist and a

behavioural health expert. In tandem, we will work with

an existing technology vendor to programme ReACT

algorithms to allow for tailored intervention delivery.

We will conduct usability testing of an alpha version

of ReACT with a sample of 20 target users to assess

acceptability and usability of our mHealth intervention.

Participants will complete a 4-week run-in period to

monitor their adherence with all ReACT features turned

off. Subsequently, participants will complete a 4-week

intervention period with all ReACT features activated.

The study started in October 2018 and is scheduled to

conclude in late 2019.

Ethics and dissemination Institutional review board

approval was obtained at the University of Kansas and

the University of Florida. We will submit study ndings

for presentation at national research conferences that

are well attended by a mix of psychologists, allied health

professionals and physicians. We will publish study

ndings in peer-reviewed journals read by members of the

psychology, nursing and pulmonary communities.

INTRODUCTION

Asthma affects over 8% of youth and is a

leading cause of morbidity.

1 2

Some asthma

symptoms and healthcare utilisation could

be prevented via consistent engagement in

disease self-management behaviours (eg,

symptom recognition and monitoring, appro-

priate administration of medications).

2 3

Adherence to daily controller medications,

such as inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), is

central to control asthma and reduce

morbidity for youth with persistent asthma.

2

ICS adherence rates with adolescents are

often <50%,

4 5

placing them at significant

risk for reduced lung function, increased

morbidity and poor quality of life.

4 6

We

posit that the complexity of the asthma treat-

ment regimen coupled with still-developing

executive functioning and problem-solving

Strengths and limitations of this study

► Intervention content will be developed rst with

theory and evidence-based decision-making and

rened via an iterative, user-centred approach with

target users and key stakeholders.

► Adaptive algorithms will be programmed into an ex-

isting, patient-facing asthma management platform.

► Intervention usability and acceptability will be strin-

gently assessed prior to efcacy testing to allow for

modications and improvements.

► Although we will have data on patient preferences,

usability and acceptability, the current protocol is not

designed to evaluate the efcacy of the Responsive

Asthma Care for Teens (ReACT) programme; this

limitation will be addressed in a future randomised

controlled trial.

► While medical providers were involved in the de-

velopment of interviews, content and interpretation

of results, the current protocol will not incorporate

shared decision-making between patients and pro-

viders in the intervention given the focus of ReACT.

on September 4, 2024 by guest. Protected by copyright.http://bmjopen.bmj.com/BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030029 on 20 August 2019. Downloaded from

2

CushingCC, etal. BMJ Open 2019;9:e030029. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030029

Open access

abilities makes adolescents uniquely vulnerable to subop-

timal asthma self-management through self-regulation

deficits.

7–11

The importance of self-regulation in asthma self-man-

agement is well-supported.

12–17

Because the self-regu-

lation abilities that are needed to successfully manage

one’s own asthma are linked to brain regions that are

still developing in adolescents (ie, frontal lobes respon-

sible for top-down control), external supports in the

form of parents or technology may be required to ensure

that dosing occurs as prescribed. Simply put, to develop

self-regulation, adolescents with chronic and persistent

asthma need to spend time thinking about their asthma,

medication and actively planning how to incorporate

adherence into their lives. Developmentally, adolescents’

executive functioning skills may not be ideally suited for

this task as evidenced by data indicating that adolescents

take their medication as prescribed on some occasions,

and nearly every adolescent misses some doses on some

occasions.

18 19

Similar to the problem of underdeveloped self-regu-

latory skill, it is common for adolescents with persistent

asthma to be met with barriers to ICS adherence that

they may not have the experience or cognitive develop-

ment to effectively problem-solve.

12 20

Indeed, intraper-

sonal factors such as attitudes (eg, motivation), feelings

(eg, mood, stress) and external factors such as the social

and family environment, have consistently been associ-

ated with asthma management behaviours and disease

outcomes.

13 21–26

Efficacious behavioural interventions

often attempt to actively reframe ICS adherence as central

to an adolescent’s self-concept (eg, better lung function

will allow you to pursue your interests). Once adolescents

see adherence as helping them reach their own personal

goals rather than as a chore, they are sufficiently moti-

vated to learn skills that can help ensure adherence to

ICS. To this end, adolescents are taught to identify intra-

personal and external barriers to adherence and prob-

lem-solve around those barriers. Beyond simply teaching

a formula for problem solving, many effective adherence

promotion programmes tailor intervention content to

personally salient barriers and help the adolescent iden-

tify and implement strategies specifically designed to

increase the chances of regimen success.

27–29

A persistent problem in this approach is the difficulty

of relying on infrequent face-to-face visits (eg, for clin-

ical care) to implement interventions. Smartphones are

habitually carried by >70% of adolescents

30

; as such,

mobile technology provides a readily available medium

to approximate the features of efficacious behavioural

health interventions

31 32

by leveraging passive monitoring,

data listening, preprogrammed algorithms and content

libraries focused on improving self-regulation and prob-

lem-solving skills.

33 34

Despite their potential, existing

mobile health (mHealth) interventions have been largely

developed without the benefit of behavioural theory,

use reminder-based approaches to behaviour change

and lack the kinds of tailored problem-solving training

that characterises efficacious in-person interventions

35–37

(for a systematic evaluation of behaviour change tech-

niques in current asthma self-management applications,

see Ramsey et al

37

). We believe that this, at least in part,

helps explain why very few existing mHealth interventions

for asthma medication adherence have yet to demon-

strate their efficacy beyond active controls.

38–40

There is a clear need for an mHealth intervention that

merges digital delivery modalities with the theory-based

behavioural framework and tailoring found in efficacious

in-person treatments. Recent technological advances

have catalysed the development of mobile-based interven-

tion platforms that deliver tailored support to individuals

in a timely fashion.

41 42

We propose to extend this work to

paediatric asthma by developing Responsive Asthma Care

for Teens (ReACT), an innovative adaptive mHealth inter-

vention that facilitates self-regulation by aiding adoles-

cents in self-monitoring, goal setting and problem solving

when adolescents’ adherence data indicate they need

additional support the most (figure 1). We will outline

how ReACT content will be developed, refined and tested

through an iterative user-centred design process guided

by theory and prior evidence.

METHODS AND ANALYSIS

Objectives

The aims of the study are: (1) conduct a hybrid user-cen-

tred and evidence-based design process comprising indi-

vidual interviews, crowdsourcing and advisory boards to

develop ReACT content and features; (2) test the accept-

ability and usability of ReACT in a sample of 20 adoles-

cents with persistent asthma. We hypothesise that ReACT

will be an acceptable and usable mHealth adherence

promotion intervention as determined by high accept-

ability and usability ratings and themes from think aloud

testing and qualitative one-on-one interviews with target

users.

Project overview

This multisite study will take place at the University of

Florida, University of Kansas and their affiliated clinics.

The study commenced in October 2018 and is anticipated

to be completed in late 2019. Features and intervention

content of ReACT will be developed concurrently. We will

work with a technology vendor to add functionality for

ReACT to an existing mHealth adherence monitoring

platform. We will use a strong theoretical framework and

prior evidence combined with a series of user-centred

design phases to determine what intervention content

should populate the ReACT system (design phase I).

Study team members and an advisory board will then

refine intervention content and complete preliminary

usability testing of ReACT (design phase II). Finally,

we will conduct acceptability and usability testing using

an alpha version of ReACT (see figure 2 for the study

timeline).

on September 4, 2024 by guest. Protected by copyright.http://bmjopen.bmj.com/BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030029 on 20 August 2019. Downloaded from

3

CushingCC, etal. BMJ Open 2019;9:e030029. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030029

Open access

Core ReACT functionality

We will create ReACT by expanding the capabilities of an

existing Android and iOS compatible mobile phone app

that uses an integrated mobile sensor designed to fit onto

an asthma metered dose inhaler or Diskus. The sensor

works passively to sense when ICS or short-acting beta-ag-

onist medications are dispensed. Bluetooth is used to pass

the information to the app, which has a set of optional

features (eg, provide feedback about adherence) that can

be turned on as intervention parameters dictate. Figure 3

outlines an adolescent’s intervention experience through

ReACT. Building from theory and prior evidence, core

ReACT components in sequence are: (1) core education

on asthma management and skills training content on goal

setting and problem solving,

4 43

(2) conditional activation

of ReACT features when an adolescent is <80% adherent

to their ICS, (3) an evidence-based goal-setting algorithm

that shapes adherence to dosing recommendations over

time, (4) timely assessment of an adolescent’s barriers to

adherence and (5) delivery of tailored problem-solving

training based on recent and salient barriers. Determi-

nants of self-regulation will be integrated into the core

ReACT functionality to best scaffold support for adoles-

cents, as outlined below.

ReACT will begin with an orientation module within

the app that guides the users through the platform,

core educational and skills training modules and passive

monitoring of medications. Adolescents will complete an

asthma education module based on the National Heart,

Lung and Blood Institute guidelines

44

to ensure that they

have an understanding of the importance of medication

adherence as a means to avoid asthma-related impair-

ments. Adolescents will receive skills training on empir-

ically supported techniques consistent with our guiding

self-regulation theory. Goal-setting content will use a

Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant, Time-Bound

goal framework. Problem-solving skills training will focus

on orienting to the problem, defining and formulating

the problem, generating alternative solutions, deciding

on a course of action and implementing a solution.

45 46

We will use engaging videos created by the team to deliver

content. Participants will complete the orientation

modules with study staff to encourage engagement and

provide assistance if necessary.

Figure 1 ReACT conceptual model. Black arrows represent mechanistic processes occurring during the ReACT

intervention period. Blue arrows indicate recursive processes happening repeatedly during the intervention period. ICS

adherence,adherence to inhaled corticosteroids; ReACT, Responsive Asthma Care for Teens.

Figure 2 Study timeline.

on September 4, 2024 by guest. Protected by copyright.http://bmjopen.bmj.com/BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030029 on 20 August 2019. Downloaded from

4

CushingCC, etal. BMJ Open 2019;9:e030029. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030029

Open access

ReACT will use passive sensing to objectively monitor

rates of adolescent ICS adherence throughout the inter-

vention period. The use of the ICS adherence sensor

offloads the burden of self-monitoring such that adoles-

cents do not have to remember or calculate their adher-

ence. Active intervention elements in ReACT will activate

only when an adolescent falls below a clinically derived

80% adherence threshold

47

based on a 7-day rolling

average, thus reducing intervention fatigue.

42

If an

adolescent has <80% adherence to ICS based on the 7-day

rolling average, ReACT will prompt the adolescent to set

a goal for adherence in the next 7-day period, a strategy

with demonstrated efficacy in previous asthma adherence

interventions.

48

The algorithm will only allow goals that

are reasonable given performance over the past week

to avoid overly ambitious and unattainable goals. Each

evening, the adolescent will receive a feedback message

about how much their adherence that day moved them

towards their goal, additionally facilitating the self-reg-

ulatory process of observation. Furthermore, the condi-

tional activation of the ReACT features should support

self-regulatory skills, specifically judgement, by notifying

the adolescent when his or her adherence declines.

ReACT will identify contextual barriers to ICS adher-

ence by also initiating an assessment as soon as the 7-day

rolling average indicates that adherence is <80%. Specif-

ically, adolescents will be prompted via a push notifica-

tion to complete a brief electronic momentary assessment

(EMA) survey of barriers identified from our pilot data

and design phase I to identify what barrier the prob-

lem-solving content should be tailored to address. Partic-

ipants will answer brief questions in the app regarding

barriers that got in the way of taking their ICS followed by

a rank order item denoting which one to make the focus of

their problem-solving efforts. Once a barrier is identified,

ReACT will deliver problem-solving content in the app

that is tailored to that specific barrier. For instance, if an

adolescent has identified and chooses to work on stress as

their top barrier to ICS adherence, the tailored problem

solving will deliver structured problem-solving training

using a flexible system of branching that is tailored to

stress specifically. To execute this feature, ReACT will

have several content banks that use the same structure. To

illustrate the user experience, a possible problem-solving

intervention could include: (1) defining the problem:

participants will be presented with a standard message

reflecting the problem they identified in the EMA survey;

(2) setting a realistic, achievable goal: several goals will

be presented and the participant will choose one and

receive feedback on their choice; (3) generating multiple

solutions: the participant will be asked to choose from a

list of possible solutions for the goal that they selected

in step #2; (4) evaluating pros and cons: participants will

evaluate the pros and cons of multiple solutions listed in

step #3; (5) selecting a solution: participants will choose

the solution that may work the best; (6) making an action

plan: participants will select from a list of action plans

that correspond to the solution they have selected; (7)

evaluating the outcome: after a week participants will be

asked whether they implemented the solution selected

in step #6. The goal-setting and tailored problem-solving

process should enhance one’s reaction to suboptimal

adherence by improving self-efficacy and facilitating skills

to overcome their personalised adherence barriers.

Once an adolescent receives intervention content, ReACT

will prompt adolescents to complete a survey in the app 2 days

later to assess content use. If the participant responds that

they used the intervention strategy, ReACT will assess the

participant’s confidence in their ability to repeat the plan in

the future. If the participant has not used the strategy, they

will receive a supportive prompt with options to review the

content they saw last time, see the same content in a different

Figure 3 React participant ow. Diamonds indicate intervention decision rules. EMA, electronic momentary assessment; ICS,

inhaled corticosteroids; ReACT, Responsive Asthma Care for Teens; SABA, short-acting beta-agonist.

on September 4, 2024 by guest. Protected by copyright.http://bmjopen.bmj.com/BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030029 on 20 August 2019. Downloaded from

5

CushingCC, etal. BMJ Open 2019;9:e030029. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030029

Open access

media format, review a different set of content on the same

topic or set a goal to use the strategies by a specific time in the

next 2 days. Another programme safeguard is to reduce over-

whelming participants with content; therefore, the tailored

problem-solving process (figure 3) will only run once in a

given 7-day window. This mirrors normative approaches for

in-person interventions during which only one or two new

concepts would be introduced each week.

Participants and recruitment

Participants

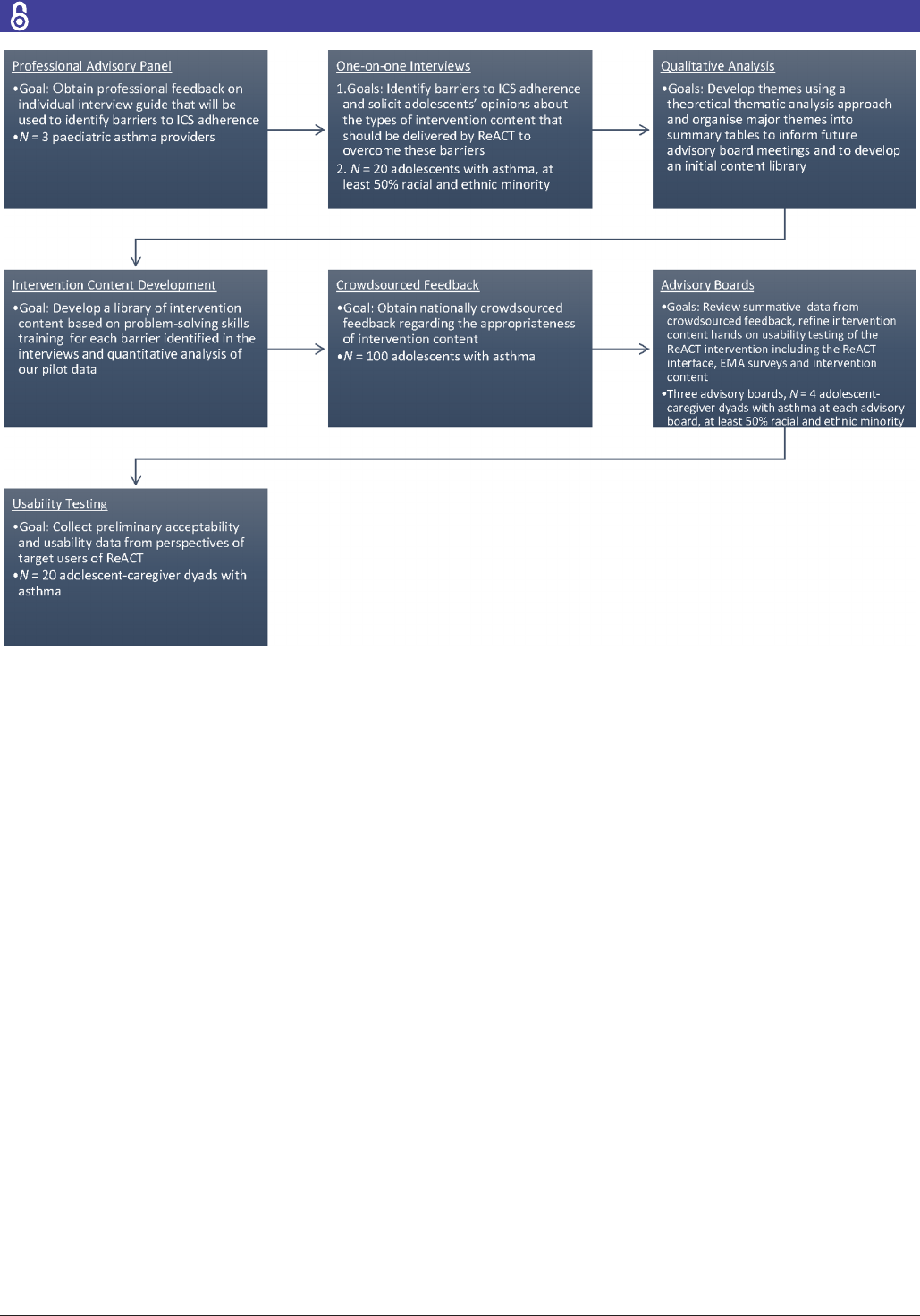

Participants will include four separate samples of adolescents

aged 13–17 years with asthma and their caregivers (figure 4).

Twenty adolescent-caregiver dyads will complete individual

interviews, 100 adolescents will provide crowdsourced feed-

back via a national online panel, 4 adolescent-caregiver dyads

will participate in advisory board meetings and 20 adoles-

cent-caregiver dyads will complete user testing of ReACT.

We intend that at least half of adolescent participants in the

interviews and advisory boards will be from racial and ethnic

minority groups.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

For interviews, advisory boards and user testing, adoles-

cents must have a physician-verified diagnosis of current

asthma with persistent symptoms requiring regular ICS

use for ≥6 months. They must have a daily ICS or ICS/

LABA prescription that is sensor-compatible, and they

and their caregivers must speak and read English. Asthma

status and prescription information will be verified via

the electronic medical record. Families will be excluded

from the study if the adolescent is currently involved in

an asthma management intervention, has a comorbid

chronic health condition that may impact lung function

or has a significant cognitive impairment or develop-

mental delay that interferes with study completion. For

crowdsourced feedback, inclusion will be determined

at the level of a national online panel, which will screen

participants for persistent asthma.

Recruitment

Participants will be recruited (1) through university-affil-

iated clinics and (2) via flyers. Research and clinic staff

members with access to the electronic medical record will

identify eligible patients with upcoming medical appoint-

ments. During these appointments, providers with clin-

ical relationships with the eligible participants will first

approach the patients to determine their interest in

hearing more about the study. Then, in coordination with

the clinic staff, research staff will meet with interested

patients to provide a study overview, complete in-person

screening for eligibility and invite participation. In

the event that a family is unable to complete screening

Figure 4 ReACT ow of formative work. EMA, electronic momentary assessment; ICS, inhaled corticosteroids; ReACT,

Responsive Asthma Care for Teens.

on September 4, 2024 by guest. Protected by copyright.http://bmjopen.bmj.com/BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030029 on 20 August 2019. Downloaded from

6

CushingCC, etal. BMJ Open 2019;9:e030029. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030029

Open access

during a clinic visit, research staff will request permission

for a member of the study team to contact patients for

screening using an institutional review board (IRB)-ap-

proved ‘consent-to-contact’ form. A member of the study

staff will then call interested participants to provide a study

overview and invite participation. In addition, IRB-ap-

proved flyers will be posted or made available in clinics,

community organisations, schools, physician offices and

common areas. Flyers will encourage families and nurses

to call our research office to learn about the project,

determine initial eligibility and if eligible, schedule an

in-person screening visit where informed consent will

be collected prior to study enrolment. Throughout all

phases of the project, participants will be incentivised and

compensated for their participation.

ReACT development

Patient and public involvement

Adolescents diagnosed with asthma, their caregivers and

paediatric asthma providers are involved in all stages of

ReACT development, as described below.

Design phase I: content development

We have developed a list of common barriers to ICS

adherence from our own pilot data and the extant paedi-

atric asthma literature. Our goal for design phase I is

to use individual interviews with adolescents diagnosed

with asthma to translate these barriers into terms easily

understood by adolescents, develop a final list of barriers

to adherence and subsequently develop a library of inter-

vention content to overcome adherence barriers that is

informed by self-regulation theory. Individual interview

participants and their caregivers will also complete asth-

ma-related measures for sample description purposes and

to obtain preliminary data on constructs of interest to the

project (table 1). Adolescent-caregiver dyads will receive

US$60 for their participation.

The study team will create an individual interview guide

that will be used to identify what barriers to adherence

are most salient to adolescents with asthma, and to solicit

their opinion about the types of intervention content that

they would prefer to receive when experiencing these

barriers. Prior to the start of individual interviews, at least

three paediatric asthma providers (eg, pulmonologists,

nurses) will provide feedback on the interview guide. All

interviews will be audio-recorded and conducted with

self-regulation theory in mind. If a component of self-reg-

ulation theory is not discussed, we will probe for content

in the omitted domain to facilitate development of inter-

vention content. Interviews will be transcribed and eval-

uated by the study team to inform digital intervention

content development (see ‘Data analysis plan’ section).

Research staff with experience developing digital

intervention content will leverage information gathered

during design phase I to develop a library of intervention

content for each barrier identified in the interviews and

quantitative analysis of our pilot data. We anticipate that

intervention content will include a combination of skills

training videos, brief text content, educational videos

and images. Delivery modality (SMS, app, etc) will be

discussed with the advisory board.

Design phase II: renement of content and preliminary usability

testing

In design phase 2, we will refine intervention content

generated in design phase I through (1) nationally crowd-

sourced feedback from adolescents with asthma and (2)

advisory board meetings. Preliminary usability testing and

iterative refinement will be conducted with our advisory

board meetings (described below).

Nationally crowdsourced feedback will be solicited

via an online panel and survey-technology provider.

Participants will be identified from panels of adoles-

cents who have agreed to participate in research. These

panels are accessed by our survey vendor through their

business-to-business partnerships. Participants will be

screened for persistent asthma using the following stan-

dard set of questions commonly used in epidemiological

trials (eg, National Health Interview Survey): (1) Have

you ever been told by a doctor, nurse or other health-

care professional that you have asthma? (2) Do you still

have asthma? Affirmative answers to both questions will

qualify an adolescent for participating.

49

Participants

will review intervention content and rate its appropriate-

ness using a dichotomous ‘yes’ (I like the message as it

is) or ‘no’ (change it to make it better) response choice.

They will receive US$15 for their participation. Content

receiving ≥60% ‘no’ votes will be discarded, and those

with ≤39% ‘no’ votes will be accepted as final interven-

tion content. Content with 40%–59% ‘no’ votes will be

revised or clarified while retaining any theoretically or

empirically derived concepts.

50

We will design surveys

to take no more than 30 min each. If necessary, we will

split the content into two surveys to keep the administra-

tion time <30 min. Although adolescent stakeholders will

be involved in developing ReACT intervention content

rated during crowdsourcing, we acknowledge that there

is a possibility that a higher than expected amount of

content will be viewed unfavourably during this phase. We

will review crowdsourcing feedback data from an initial

wave of 20 participants. In the event that >60% of content

is viewed unfavourably, we will pause crowdsourcing to

develop new intervention content.

An advisory board comprising adolescent-caregiver

dyads and study staff members will convene three times.

The first meeting will focus on reviewing summative data

and themes that emerged from crowdsourcing phase.

The second advisory board meeting will involve discus-

sion about methods to further refine intervention content

that received 40%–59% ‘no’ votes during crowdsourcing.

We will incorporate modified content that reaches group

consensus into applicable ReACT intervention content

libraries. Preliminary usability testing will take place

during the final advisory board meeting. Members will

conduct hands-on testing of ReACT alongside study staff.

We will use a ‘think aloud’ approach with members as

on September 4, 2024 by guest. Protected by copyright.http://bmjopen.bmj.com/BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030029 on 20 August 2019. Downloaded from

7

CushingCC, etal. BMJ Open 2019;9:e030029. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030029

Open access

they explore components of the ReACT interface (eg,

layout, visual feedback), answer EMA questions and view

intervention content.

51

This process more closely approx-

imates actual use and will enable us to receive feedback

in real-time. The study team will transcribe participants’

commentary during testing for review. Results of the

‘think aloud’ testing will help to inform final design deci-

sions in ReACT.

51

For instance, whether content is deliv-

ered using SMS, in-app, push notification or some other

medium will be informed by user preferences. Advisory

board participants and their caregivers will also complete

asthma-related measures to pilot data collection proce-

dures and provide baseline descriptive statistics (table 1).

Adolescent-caregiver dyads will receive US$50 for each

advisory board meeting they attend.

Acceptability and usability testing of ReACT

In the final phase, adolescents will conduct user testing

with the alpha version of ReACT. The overarching

goal is to gather acceptability and usability data from

the perspectives of target users of ReACT. A sample of

20 participants will complete a 4-week run-in period to

Table 1 ReACT outcome measures

Outcome Measure Assessment schedule

Demographics A caregiver-report questionnaire assesses adolescent and family demographic

characteristics.

II, AB, UT

Asthma morbidity A caregiver-report questionnaire assesses frequency of asthma symptoms,

exacerbations, activity limitations, missed school days due to asthma, ED visits

and hospitalisations.

II, AB, UT

Medical information Medical chart review assesses prescribed ICS regimen and dosage. II, AB, UT

Asthma knowledge

and skills

The Asthma Child Knowledge and Skills Questionnaire,

12

a modied version

of the Children’s Asthma Knowledge Questionnaire,

59

is a 30-item adolescent-

report measure that assesses both asthma knowledge and self-assessment of

skills required for taking medication.

II, AB, UT

Asthma control The Asthma Control Test

60

is a 5-item, validated, adolescent-report

questionnaire that assesses asthma control in past 4 weeks.

II, AB, UT

Asthma

management

The Asthma Management Efcacy Questionnaire

61

is a 14-item, validated,

adolescent-report questionnaire that assesses asthma self-management

behaviours.

II, AB, UT

Asthma adherence The Medication Adherence Report Scale for Asthma

62

is a 10-item, validated,

adolescent-report measure of ICS adherence.

II, AB, UT

Self-regulation The Treatment Self-Regulation Questionnaire-Asthma

63

is a 15-item,

adolescent-report measure that assesses motivation for using controller

medication.

II, AB, UT

Stress The Adolescent Stress Questionnaire

64

Revised is a 58-item, validated,

adolescent-report questionnaire that assesses stressors in adolescence.

II, AB, UT

Social support The Social Support Questionnaire

65

is a 27-item, validated, adolescent-report

measure of social support.

II, AB, UT

Problem solving The Social Problem Solving Inventory-Revised: Short Form

66

is a 25-item,

validated, adolescent-report measure that assesses problem-solving orientation

and skills in everyday life.

II, AB, UT

Asthma-related

quality of life

PAQLQ

67

is a 23-item, validated, adolescent-report questionnaire that measures

extent of asthma impairment in quality of life.

II, AB, UT

Acceptability The ReAct Satisfaction Questionnaire is an 8-item modication of the Client

Satisfaction Questionnaire

56

that assesses overall participant satisfaction with

the ReACT intervention. Semi-structured interviews assess what adolescents

like and do not like about ReACT, its relevance and its perceived helpfulness

with medication adherence.

UT

Usability The Health Information Technology Usability Evaluation Scale

57

is a 20-item,

validated questionnaire that assesses perceived usefulness, impact on disease,

perceived ease of use and user control. Think aloud testing gathers stream of

consciousness data regarding thoughts and feelings of users as they complete

specied tasks. Semi-structured interviews assess the look and feel of ReACT,

ease of navigation and experience accessing intervention content.

UT

AB,advisory boards; ED, emergency department; ICS, inhaled corticosteroids; II, design phase I individual interviews;PAQLQ, Pediatric

Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire; ReACT, Responsive Asthma Care for Teens; UT,user testing.

on September 4, 2024 by guest. Protected by copyright.http://bmjopen.bmj.com/BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030029 on 20 August 2019. Downloaded from

8

CushingCC, etal. BMJ Open 2019;9:e030029. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030029

Open access

monitor their adherence with all ReACT features turned

off. Subsequently, study staff will meet with participants to

complete ReACT orientation. This visit will ensure that

participants are able to download and use ReACT, and

that relevant ReACT components (eg, asthma education

and skills training videos) are accessed before beginning.

Participants will complete asthma-related study question-

naires (table 1) and then begin a 4-week intervention

period with all ReACT features activated. Notably, accept-

ability and usability measures will be administered at a

final study visit at the conclusion of the 4-week interven-

tion period. Again, participants’ comments and sugges-

tions during the final study visit will be transcribed for

review.

Data analysis plan

Individual interviews

Study staff will enter transcribed files and expanded notes

into NVivo. We will code and aggregate interviews using

a theoretical thematic analysis approach to developing

themes.

52–54

Our theoretical thematic analysis approach

will use an a priori theoretical framework guided by

self-regulation theory, informed by advisory board meet-

ings. The investigators will mark comments identified to

represent discrete thoughts or themes using a semantic

analysis, and they will use an essential realist approach to

arrive at themes.

52

These patterns or themes will comprise

the initial set of categories. Research staff will then recode

the data using these categories and organise major themes

into summary tables to inform initial development of a

digital content library. Interviews will continue until no

new themes emerge in the data coding process (ie, satu-

ration).

55

After the coding process is complete, data will

be described descriptively.

ReACT acceptability

Acceptability of ReACT will be determined in two ways

during the usability testing phase. First, the ReACT Satis-

faction Questionnaire

56

will assess overall satisfaction,

perceptions regarding how helpful ReACT could be in

managing asthma and whether adolescents would recom-

mend ReACT to friends with asthma on a 4-point Likert

scale. An average rating of 3 (mostly satisfied) will be

considered a successful outcome. Second, the semi-struc-

tured interviews will solicit adolescent feedback about

ReACT. Our comprehensive interview guide will cover

a range of topics, including: (1) perceived usefulness of

ReACT; (2) how effective ReACT might be in changing

asthma self-management behaviours and (3) suggestions

on further refining ReACT (eg, incorporating other indi-

viduals). Qualitative data analysis will help determine

overall project success. The process for identifying themes

will be similar to the process from the earlier interview

phase, but in this case we will use an entirely de novo

process of identifying themes.

52

We will mark comments

identified to represent discrete thoughts or themes using

a semantic analysis, and we will use an essential realist

approach to arrive at themes.

52

In particular, we will be

attentive to themes that relate to the acceptability, useful-

ness and user experience of ReACT. Themes that indicate

that ReACT was perceived to be effective, appropriately

tailored and acceptable burden will be the criteria for

success.

ReACT usability

Usability will be determined in three ways. First, an

average rating of 3 (agree) on the Health Information

Technology Usability Evaluation Scale

57

will be a criterion

for success. Second, themes from think aloud testing that

suggest adolescents can navigate the ReACT interface

intuitively and with minimal difficulty will be markers of

success. Finally, our semi-structured interview will ask for

feedback regarding: (1) the layout of the ReACT inter-

face; (2) the navigation experience; (3) clarity of the

wording; (4) clarity of the video content and (5) ways to

improve the usability and content of ReACT. These data

will be used to inform future refinements of ReACT in

advance of a subsequent trial.

Ethics and dissemination

All research team members will complete certification

in topics related to the responsible conduct of research.

To minimise risk from research participation, potential

subjects will be fully informed regarding the purpose,

process and amount of time required for participation.

It is possible that research staff will identify an adolescent

whose asthma appears undertreated. Research staff will

review all cases with local medical personnel and facilitate

a referral for evaluation and appropriate medication if

indicated.

We plan to disseminate findings from the current

project to multiple audiences including the local medical

community and the broader scientific community via

local and national presentations at relevant conferences

and meetings. Beyond paediatric asthma, we also envision

that the ReACT infrastructure and design process can be

used to develop and test behaviour change interventions

in other disease populations. If successful, this would be

a significant step towards the 2016 National Institutes of

Health-Wide Strategic Plain goal of using mHealth to

‘enhance health promotion and disease prevention’.

58

Limitations

The current project is a pilot feasibility, acceptability and

usability study in a targeted sample (ie, adolescents with

chronic and persistent asthma), who also have a high need

for this type of intervention. As such, we will not be able

to contribute knowledge about the feasibility of ReACT

in all of the populations it might benefit (eg, adults with

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease). Moreover, the

current project is not powered to understand heteroge-

neity of outcomes across sex, socioeconomic status, race,

culture and literacy levels. The protocol will not incor-

porate shared decision-making between patients and

providers in the intervention given the focus of ReACT.

ReACT does not target all of the factors that might

on September 4, 2024 by guest. Protected by copyright.http://bmjopen.bmj.com/BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030029 on 20 August 2019. Downloaded from

9

CushingCC, etal. BMJ Open 2019;9:e030029. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030029

Open access

influence adherence. Specifically, structural issues such

as inadequate insurance coverage will not be addressed

in the current protocol. At this stage, ReACT does not

involve providers at least in part because there are already

other commercial systems that do a good job of achieving

that function. The novelty of ReACT is to identify the

developmentally appropriate individual-level interven-

tions that can increase adherence.

Author afliations

1

Clinical Child Psychology Program and Schiefelbusch Institute for LifeSpan Studies,

University of Kansas

2

Department of Clinical & Health Psychology, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL

3

Department of Pediatrics, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City,

Kansas, USA

4

Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, Brown University, Providence,

Rhode Island, USA

5

Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Pennsylvania, USA

6

Department of Pediatrics, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida, USA

7

Division of Allergy and Immunology, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas

City, KS, USA

8

Life Span Institute, University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas, USA

9

Department of Psychology, Drexel University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA

Contributors DAF and CCC conceived the study. DAF, CCC, SPa, SG, ELM, SPr and

JMS developed the protocol. DAF, CCC, NK-S, AO, KKF and AMN were involved in

drafting of the article. Specically, DAF and CCC collaboratively wrote the text, NK-S

and AO edited the text, and created gures. KKF and AMN provided expertise and

section edits on the statistical approach and features of problem-solving therapy.

SPa and ELM provided expertise and writing about qualitative work. JMS provided

expertise and writing about adaptive interventions. All authors completed a critical

revision of the article and approved the nal text. DAF and CCC contributed equally

to the paper as joint rst authors (order determined by coin ip).

Funding This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant

number 1R56HL141394-01A1.

Competing interests None declared.

Patient consent for publication Not required.

Ethics approval Institutional review board approval was obtained at the University

of Kansas and the University of Florida.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Open access This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the

Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which

permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially,

and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is

properly cited, appropriate credit is given, any changes made indicated, and the use

is non-commercial. See: http:// creativecommons. org/ licenses/ by- nc/ 4. 0/.

REFERENCES

1. Akinbami LJ, Simon AE, Rossen LM. Changing Trends in Asthma

Prevalence Among Children. Pediatrics 2016;137:e20152354.

2. Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma (EPR-3).

Bethesda, MD, 2007.

3. Guevara JP, Wolf FM, Grum CM, et al. Effects of educational

interventions for self management of asthma in children and

adolescents: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ

2003;326:1308–9.

4. Morton RW, Everard ML, Elphick HE. Adherence in childhood

asthma: the elephant in the room. Arch Dis Child 2014;99:949–53.

5. Bender BG. Nonadherence to asthma treatment: Getting unstuck. J

Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2016;4:849–51.

6. Anderson WC, Szeer SJ. New and future strategies to improve

asthma control in children. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015;136:848–59.

7. Drotar D, Bonner MS. Inuences on adherence to pediatric asthma

treatment: a review of correlates and predictors. J Dev Behav Pediatr

2009;30:574–82.

8. D'Zurilla TJ, Maydeu-Olivares A, Kant GL. Age and gender

differences in social problem-solving ability. Pers Individ Dif

1998;25:241–52.

9. Jaffee WB, D'Zurilla TJ. Adolescent problem solving, parent problem

solving, and externalizing behavior in adolescents. Behav Ther

2003;34:295–311.

10. Muscara F, Catroppa C, Anderson V. Social problem-solving skills

as a mediator between executive function and long-term social

outcome following paediatric traumatic brain injury. J Neuropsychol

2008;2:445–61.

11. McGee CL, Fryer SL, Bjorkquist OA, et al. Decits in social problem

solving in adolescents with prenatal exposure to alcohol. Am J Drug

Alcohol Abuse 2008;34:423–31.

12. Rhee H, Belyea MJ, Ciurzynski S, et al. Barriers to asthma self-

management in adolescents: Relationships to psychosocial factors.

Pediatr Pulmonol 2009;44:183–91.

13. Rhee H, Belyea MJ, Brasch J. Family support and asthma outcomes

in adolescents: barriers to adherence as a mediator. J Adolesc Health

2010;47:472–8.

14. Modi AC, Quittner AL. Barriers to treatment adherence for children

with cystic brosis and asthma: What gets in the way? J Pediatr

Psychol 2006;31:846–58.

15. Buston KM, Wood SF. Non-compliance amongst adolescents with

asthma: listening to what they tell us about self-management. Fam

Pract 2000;17:134–8.

16. Bender BG, Bender SE. Patient-identied barriers to asthma

treatment adherence: responses to interviews, focus groups, and

questionnaires. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 2005;25:107–30.

17. Clark NM, Gong M, Kaciroti N. A model of self-regulation for control

of chronic disease. Health Educ Behav 2001;28:769–82.

18. Gray WN, Netz M, McConville A, et al. Medication adherence in

pediatric asthma: A systematic review of the literature. Pediatr

Pulmonol 2018;53:668–84.

19. Bender B, Zhang L. Negative affect, medication adherence, and

asthma control in children. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2008;122:490–5.

20. Modi AC, Quittner AL. Barriers to treatment adherence for children

with cystic brosis and asthma: what gets in the way? J Pediatr

Psychol 2006;31:846–58.

21. Riekert KA, Borrelli B, Bilderback A, et al. The development of

a motivational interviewing intervention to promote medication

adherence among inner-city, African-American adolescents with

asthma. Patient Educ Couns 2011;82:117–22.

22. Christiaanse ME, Lavigne JV, Lerner CV. Psychosocial aspects of

compliance in children and adolescents with asthma. J Dev Behav

Pediatr 1989;10:75–80.

23. Fiese BH, Wamboldt FS, Anbar RD. Family asthma management

routines: connections to medical adherence and quality of life. J

Pediatr 2005;146:171–6.

24. Penza-Clyve SM, Mansell C, McQuaid EL. Why don't children

take their asthma medications? A qualitative analysis of children's

perspectives on adherence. J Asthma 2004;41:189–97.

25. Leeman J, Crandell JL, Lee A, et al. Family functioning and the well-

being of children with chronic conditions: A meta-analysis. Res Nurs

Health 2016;39:229–43.

26. Wolf F, Guevara J, Grum C, et al. Educational interventions

for asthma in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

2010;1:CD000326.

27. Naar-King S, Ellis D, King PS, et al. Multisystemic therapy for high-

risk African American adolescents with asthma: a randomized clinical

trial. J Consult Clin Psychol 2014;82:536–45.

28. Nezu AM, Nezu CM, Perri MG. Problem solving to promote treatment

adherence. In: O’Donohue WT, Levensky ER, eds. Promoting

Treatment Adherence: A Practical Handbook for Health Care

Providers. New York: SAGE Publications, 2006:135–48.

29. Duncan CL, Hogan MB, Tien KJ, et al. Efcacy of a parent-youth

teamwork intervention to promote adherence in pediatric asthma. J

Pediatr Psychol 2013;38:617–28.

30. Lenhart A. Teens, Social Media & Technology Overview 2015.

2015 http://www. pewinternet. org/ 2015/ 04/ 09/ teens- social- media-

technology- 2015/

31. Ritterband LM, Gonder-Frederick LA, Cox DJ, et al. Internet

interventions: In review, in use, and into the future. Prof Psychol

2003;34:527–34.

32. Schueller SM, Muñoz RF, Mohr DC. Realizing the Potential

of Behavioral Intervention Technologies. Curr Dir Psychol Sci

2013;22:478–83.

33. Riley WT, Rivera DE, Atienza AA, et al. Health behavior models in the

age of mobile interventions: are our theories up to the task? Transl

Behav Med 2011;1:53–71.

34. Mohr DC, Schueller SM, Montague E, et al. The behavioral

intervention technology model: an integrated conceptual and

technological framework for eHealth and mHealth interventions. J

Med Internet Res 2014;16:e146.

on September 4, 2024 by guest. Protected by copyright.http://bmjopen.bmj.com/BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030029 on 20 August 2019. Downloaded from

10

CushingCC, etal. BMJ Open 2019;9:e030029. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030029

Open access

35. Breland JY, Yeh VM, Yu J. Adherence to evidence-based guidelines

among diabetes self-management apps. Transl Behav Med

2013;3:277–86.

36. Fedele DA, Cushing CC, Fritz A, et al. Mobile health interventions for

improving health outcomes in youth: A meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr

2017;171:461.

37. Ramsey RR, Caromody JK, Voorhees SE, et al. A systematic

evaluation of asthma management apps examining behavior change

techniques. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2019.

38. Miller L, Schüz B, Walters J, et al. Mobile technology interventions

for asthma self-management: Systematic review and meta-Analysis.

JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2017;5:e57.

39. T- jung Y, Joeng HY, Hill TD, et al. Using SMS to provide continuous

assessment and improve health outcomes for children with asthma.

IHI’ 12 Proceedings of the 2nd ACM SIGHIT International Health

Informatics Symposium. Miami, FL, 2012:621–30.

40. Chan AH, Stewart AW, Harrison J, et al. The effect of an electronic

monitoring device with audiovisual reminder function on adherence

to inhaled corticosteroids and school attendance in children

with asthma: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med

2015;3:210–9.

41. Smyth JM, Heron KE. Is providing mobile interventions “just-in-

time” helpful? an experimental proof of concept study of just-in-

time intervention for stress management. IEEE Wireless Health

Conference. Bethesda, MD, 2016:89–95.

42. Nahum-Shani I, Smith SN, Spring BJ, et al. Just-in-Time Adaptive

Interventions (JITAIs) in mobile health: Key components and design

principles for ongoing health behavior support. Ann Behav Med

2018;52:446-462.

43. Klok T, Kaptein AA, Brand PLP. Non-adherence in children with

asthma reviewed: The need for improvement of asthma care and

medical education. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2015;26:197–205.

44. National Asthma Education and Prevention Program. Expert Panel

Report 3 (EPR-3): Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of

Asthma-Summary Report 2007. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007;120(5

Suppl):S94–138.

45. D’Zurilla TJ, Nezu AM, Therapy P-S. In: Dobson KS, ed. Handbook of

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapies. 3rd edn. New York, NY: The Guilford

Press, 2010:197–225.

46. Nezu AM, Nezu CM. Emotion-Centered Problem-Solving Therapy:

Treatment Guidlelines. New York: Springer Publishing, 2019.

47. Lasmar L, Camargos P, Champs NS, et al. Adherence rate to

inhaled corticosteroids and their impact on asthma control. Allergy

2009;64:784–9.

48. Otsuki M, Eakin MN, Rand CS, et al. Adherence feedback to improve

asthma outcomes among inner-city children: a randomized trial.

Pediatrics 2009;124:1513–21.

49. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). CDC - Asthma -

National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) Data.

50. Woolford SJ, Barr KL, Derry HA, et al. OMG do not say LOL: obese

adolescents' perspectives on the content of text messages to

enhance weight loss efforts. Obesity 2011;19:2382–7.

51. Ben-Zeev D, Kaiser SM, Brenner CJ, et al. Development and

Usability Testing of FOCUS: A Smartphone System for Self-

Management of Schizophrenia. 2013.

52. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res

Psychol 2006;3:77–101.

53. Corbin J, Strauss AL. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques

and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks,

California: SAGE Publications, 2008.

54. Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldaña J. Qualitative Data Analysis

: A Methods Sourcebook. 3rd edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE

Publicatitons, 2013.

55. Wu YP, Thompson D, Aroian KJ, et al. Commentary: Writing

and evaluating qualitative research reports. J Pediatr Psychol

2016;41:493–505.

56. Larsen DL, Attkisson CC, Hargreaves WA, et al. Assessment of

client/patient satisfaction: development of a general scale. Eval

Program Plann 1979;2:197–207.

57. Schnall R, Cho H, Liu J. Health Information Technology Usability

Evaluation Scale (Health-ITUES) for Usability Assessment of

Mobile Health Technology: Validation Study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth

2018;6:e4.

58. Department of Health & Human Services. NIH-Wide Strategic Plan:

Fiscal Years 2016-2020. 2015. https://www. nih. gov/ sites/ default/

les/ about- nih/ strategic- plan- fy2016- 2020- 508. pdf [Accessed 18

Jan 2019].

59. Bartholomew LK, Gold RS, Parcel GS, et al. Watch, Discover, Think,

and Act: evaluation of computer-assisted instruction to improve

asthma self-management in inner-city children. Patient Educ Couns

2000;39(2-3):269–80.

60. Liu AH, Zeiger R, Sorkness C, et al. Development and cross-

sectional validation of the Childhood Asthma Control Test. J Allergy

Clin Immunol 2007;119:817–25.

61. Bursch B, Schwankovsky L, Gilbert J, et al. Construction and

validation of four childhood asthma self-management scales: parent

barriers, child and parent self-efcacy, and parent belief in treatment

efcacy. J Asthma 1999;36:115–28.

62. Cohen JL, Mann DM, Wisnivesky JP, et al. Assessing the validity

of self-reported medication adherence among inner-city asthmatic

adults: the Medication Adherence Report Scale for Asthma. Ann

Allergy Asthma Immunol 2009;103:325–31.

63. Levesque CS, Williams GC, Elliot D, et al. Validating the theoretical

structure of the Treatment Self-Regulation Questionnaire

(TSRQ) across three different health behaviors. Health Educ Res

2007;22:691–702.

64. Byrne DG, Davenport SC, Mazanov J. Proles of adolescent stress:

the development of the adolescent stress questionnaire (ASQ). J

Adolesc 2007;30:393–416.

65. Sarason IG, Levine HM, Basham RB, et al. Assessing social

support: The Social Support Questionnaire. J Pers Soc Psychol

1983;44:127–39.

66. D'Zurilla TJ, Nezu AM. Development and preliminary evaluation of the

Social Problem-Solving Inventory. Psychol Assess 1990;2:156–63.

67. Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Feeny DH, et al. Measuring quality of life in

children with asthma. Qual Life Res 1996;5:35–46.

on September 4, 2024 by guest. Protected by copyright.http://bmjopen.bmj.com/BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030029 on 20 August 2019. Downloaded from