Page i Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................... 1

INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................... 3

Methodology ........................................................................................................................................ 3

About the Sample ................................................................................................................................. 3

RESULTS ..................................................................................................................................................... 4

Qualifications and Experience .............................................................................................................. 4

Experience .................................................................................................................................. 6

Certifications ............................................................................................................................... 9

Career Type ....................................................................................................................................... 11

Applied Employment .......................................................................................................................... 13

Industry ..................................................................................................................................... 13

Job Title .................................................................................................................................... 14

Academic Employment ....................................................................................................................... 16

Geographic Location .......................................................................................................................... 19

Bonuses ............................................................................................................................................. 21

Raises ................................................................................................................................................ 23

Benefits .............................................................................................................................................. 25

Retirement Benefits ................................................................................................................... 25

Leave, Health, and Disability Insurance Benefits ....................................................................... 26

Professional Development and Education Benefits .................................................................... 31

Other Benefits ........................................................................................................................... 32

Supplemental Income ......................................................................................................................... 35

The Impact of COVID-19 .................................................................................................................... 36

COVID-19 Impact on Remote Work Arrangements .................................................................... 36

COVID-19 Impact on Employment ............................................................................................. 39

COVID-19 Impact on Work Hours .............................................................................................. 45

COVID-19 Impact on Benefits ................................................................................................... 45

Caregiving .......................................................................................................................................... 47

Demographics .................................................................................................................................... 50

Age ........................................................................................................................................... 50

Disability.................................................................................................................................... 50

Gender ...................................................................................................................................... 51

Race and Ethnicity .................................................................................................................... 55

Race by Gender ........................................................................................................................ 56

Degree Type ............................................................................................................................. 57

Page ii Table of Contents

CONCLUSION ............................................................................................................................................ 59

APPENDIX .................................................................................................................................................. 60

Historical Comparisons....................................................................................................................... 60

INDEX ......................................................................................................................................................... 63

List of Tables ...................................................................................................................................... 63

List of Figures..................................................................................................................................... 64

ABOUT SIOP .............................................................................................................................................. 65

ABOUT HUMRRO ...................................................................................................................................... 65

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................................................................................................... 66

Executive Summary

Page 1

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

2022 Income and

Employment Report

The Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology (SIOP) publishes the Income

and Employment Report to track salary and employment trends for industrial and organizational

psychologists (I-Os). Below are key points from the 2021 SIOP Salary Survey.

Salary increases since 2018

11%

16.2%

Average Wage Index

Increase since 2018

Consumer Price Index

Increase since 2018

Doctorate Income

9.6%

Master’s Income

12.4%

62% of doctorate-level respondents are

practitioners and

38% work in academia.

97.8% of master’s-

level respondents

work as practitioners.

Practitioners’ median

income is

19.5% higher

than that of academics.

Among doctorate-level

practitioners, independent

consultants earned the highest

median salary

(

$350,000

)

.

I-O psychologist salaries increased less than

the average wage index since 2018. Master’s-

level salaries increased more than the ination

rate, but doctorate-level salaries did not.

19.5% 38%62%

Among master’s-level practitioners,

those working in the technology

industry earned the highest

median salary

(

$121,729*

)

.

(*for industries with n > 10)

Academics in business

schools had a higher median

income

(

$143,559

)

than those

in psychology departments

(

$92,000

)

.

97.8%

EDUCATIONJOB SECTOR

Executive Summary

Page 2

2022 Income and

Employment Report

Most I-Os experienced no change in employment

or income due to COVID-19 in 2020

(

73.2%

)

or in 2021

(

88.5%

)

. Salary, benet, and bonus

reductions were the most common impacts in

2020

(

8.4%, 8.9%, and 7%, respectively

)

. Those

impacts dropped by about two-thirds in 2021.

The gender wage gap has narrowed since the

2019 report.

The median income for women increased in 2021

to

94% of men’s median income, and the pay

difference was not statistically signican

t.

Before the pandemic,

17% of I-Os worked fully remotely. In 2021, 42% of I-Os reported working fully remotely.

Remote work status did not impact pay.

9%

The largest

concentration of

respondents work in

the D.C. metro area.

$133,891

Master’s-level I-Os working in the

Chicago metro area earned the highest

median income (Adjusted for cost of living).

$239,425

Doctorate-level I-Os

working in the Houston

metro area earned the

highest median income

(Adjusted for cost of living).

The most common COVID-related benets offered

by employers in 2020 and 2021 were exible work

arrangements

(

45% and 37%, respectively

)

,

additional time off

(

32% and 26%

)

, and access to

Personal Protective Equipment

(

27% and 26%

)

.

LOCATIONCOVID-19GENDER

Page 3 Introduction

INTRODUCTION

Methodology

The 2021 SIOP Income and Employment Survey

asked members about their income and work

arrangements in 2020 and 2021. The survey was

developed and administered by SIOP’s Institutional

Research Committee (IRC) Salary Survey

Subcommittee in partnership with Mercer|Sirota.

Email invitations to complete the survey were sent to

5,146 SIOP members. We received 1,213 responses;

a 21% percent response rate. Human Resources

Research Organization (HumRRO) analyzed the

survey results and developed this report. To protect

respondent anonymity, we report results for groups

and subgroups with no fewer than 10 respondents. In

some cases, this limited the level of depth and detail

of subgroup analyses but we are confident that these

findings are sufficiently representative of the state of

income and employment for SIOP members.

About the Sample

After data cleaning procedures, the 2021 SIOP Salary Survey received 1,074 responses from members

(Student members are not included in the sample). Because 96% (n = 1,027) of respondents were employed

full-time and only 4% (n = 47) were employed part-time or did not specify the number of hours they worked,

we only included responses in our analyses from members who worked full-time in 2021. Full-time

employees worked 44.5 hours per week on average (median = 42), a continuing decrease from 2019 (mean

= 45.5, median = 45) and 2015 (mean = 47.8, median = 48).

As in previous reports, the sample consists of more practitioners than academics. Of those who reported

career type, 72% (n = 739) were practitioners and 28% (n = 288) worked in academia. Practitioners worked

in a wide variety of industries, with the largest percentage working in consulting firms (38% of doctorate

practitioners and 35% of master’s-level practitioners) or in the tech industry (25% of doctorate practitioners

and 19% of master’s-level practitioners). As in previous years, a majority of the sample reported their

highest degree was a doctorate, with 72% (n = 740) holding doctorate degrees and 27% (n = 276) holding

master’s degrees, while 1% (n = 11) of respondents held bachelor’s degrees or did not report degree status.

Another continuing trend is the larger representation of women than men in the sample, with women making

up 53% (n = 543) of respondents and men accounting for 46% (n = 465). Demographic characteristics of the

current sample compared to previous survey administrations can be found in the Appendix.

As in past years, this report provides findings and insights about how and where I-Os work and current

income and benefit trends in the field. The 2021 survey was unique from past surveys in several respects.

The most profound of these differences was the inclusion of questions about the impact of COVID-19. The

pandemic affected nearly every area of life in 2020 and 2021, and the current survey included questions

about remote work, caregiving, and changes in employment, income, and benefits due to COVID-19.

Responses to this additional survey content showed that on the whole, I-O careers fared well during the

pandemic and companies where I-Os worked responded to employees’ changing needs by offering

additional benefits. These findings are discussed in later sections of this report.

Page 4 Results

RESULTS

Qualifications and Experience

Because an overwhelming majority of

respondents reported having earned a doctorate

degree or a master’s degree, this report focuses

on metrics for those two groups. Median income

for master’s-level respondents increased more

than the median income for doctorate-level

respondents from 2018 to 2021. Salaries for

doctorate-level respondents in the sample rose by

9.6% since 2018, while master’s-level salaries

rose by 12.4%. The U.S. Consumer Price Index

(CPI) inflation rate increased 11%

1

between 2018

and 2021, meaning master’s-level incomes kept

abreast of inflation while doctorate-level salaries

did not. However, income gains for both master’s-

level and doctorate-level respondents fell far short

of the U.S. Average Wage Index increase of

16.2%

2

over the same period.

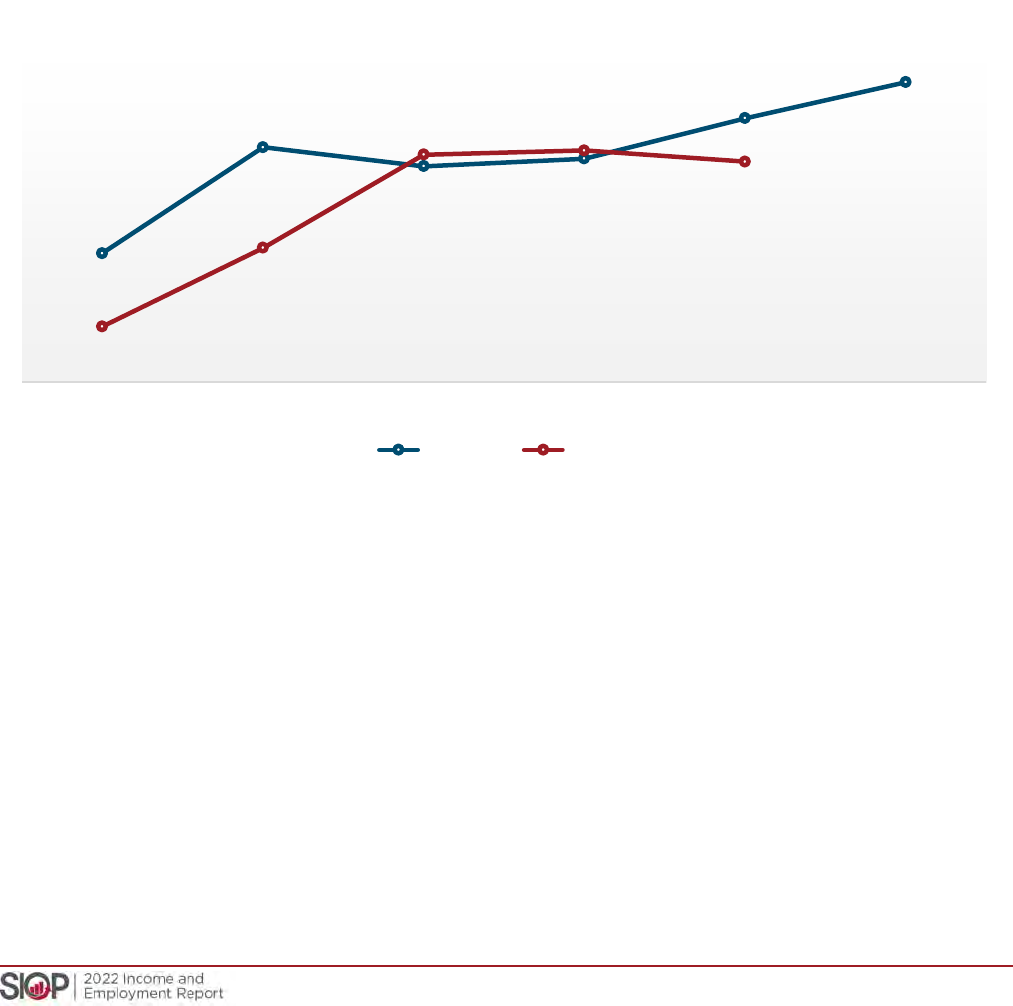

Figure 1 shows median salaries by degree for each report year. For 2021, the median salary was $137,000

for doctorate-level respondents and $100,000 for master’s-level respondents. The difference between

median salaries for doctorate holders and for master’s degree holders decreased from 41% in 2018 to 37%

in 2021. The trend over time (Figure 2) shows doctorate-level salaries have ranged between 34% (in 2000)

and 47% (in 2011) higher than master’s-level salaries since 1997. However, since 2014 the pay differential

has been narrowing (Figure 2).

“For 2021, the median salary was

$137,000 for doctorate-level respondents

and $100,000 for master’s-level respondents.”

1

The CPI inflation rate between 2018 and 2021 was calculated using data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics at

https://www.bls/gov/timeseries/CUUR0000SA0. The increase was calculated by comparing the December 2021 CPI with the

December 2018 CPI.

2

Average Wage Index (AWI) data was retrieved from the U.S. Social Security Administration (S.S.A.) AWI tables at

https://www.ssa.gov/OACT/COLA/AWI.html. Note: AWI data from the S.S.A. are average per worker, so industries with larger

numbers of workers have more weight.

Page 5 Results

Figure 1. Median Income Over Time by Degree Level

Figure 2. Percent Difference Between Doctorate-level and Master's-level Median Salaries

Over Time

$43K

$60K

$71K

$80K

$83K

$90K

$84K

$88K

$92K

$99K

$102K

$105K

$110K

$113K

$112K

$118K

$125K

$137K

$43K

$52K

$60K

$55K

$58K

$67K

$60K

$65K

$68K

$72K $72K

$75K

$75K

$81K

$77K

$85K

$89K

$100K

1982 1988 1994 1997 1999 2000 2002 2003 2005 2006 2008 2009 2011 2012 2014 2015 2018 2021

Doctorate Master's

0%

17%

19%

46%

43%

34%

40%

35%

35%

37%

42%

41%

47%

40%

46%

41%

41%

37%

1982 1988 1994 1997 1999 2000 2002 2003 2005 2006 2008 2009 2011 2012 2014 2015 2018 2021

Page 6 Results

Experience

Overall, doctorate-level income was 37% higher than that of master’s level respondents (t = 8.0, df = 953.1,

p < .001)

3

. Beyond educational attainment, work experience has a substantial impact on I-Os’ income. Time

since degree represents work experience and skill acquisition, both of which are associated with higher

earning potential. Tables 1 and 2 show median and mean salary along with percentile distributions for

doctorate-level and master’s-level members by years since highest degree earned.

Unlike in past reports, the income trajectory for doctorate-level I-Os did not consistently increase with years

since degree. Notably, salary percentiles for the 20-to-24-years group are slightly inflated compared to their

adjacent cohorts, suggesting that this cohort contains some extremely high incomes. Salaries for the 15-to-19-

years cohort at or below the 50

th

percentile are slightly deflated compared to the 10-to-14-years cohort. To

better understand the trends in median income, we examined additional characteristics of doctorate holders for

those at 15-to-19 years since degree and those at 25-or-more years since degree. In the 15-to19-years cohort,

the median salary for men ($150,559) and women ($146,694) were both close to the overall median. Within

the 25-or-more-years cohort, the median salary was $196,500 for men and $153,562 for women (although this

difference was not statistically significant), with women making up about 41% of this cohort. In the remaining

cohorts, median salaries for men and for women were similar, with median salaries for women being higher

than for men in the 5-to-9-years, 10-to-14-years, and 20-to-24-years cohorts. The gender effect for the 25-or-

more years cohort may contribute to the relatively lower salaries in the 25-or-more-years since degree group.

Gender differences in pay are discussed in more detail in a later section of the report.

Table 1. Base Salary by Years Since Doctorate Degree

Years Since Degree

< 2 2-4 5-9 10-14 15-19 20-24 25+

n 25 107 157 87 71 57 99

Median $100,000 $110,000 $130,000 $150,000 $149,000 $190,000 $160,000

Mean $109,214 $119,192 $142,950 $168,021 $172,158 $278,667 $217,747

Percentile

90th $142,400 $170,200 $212,000 $225,000 $245,000 $320,938 $300,000

75th $124,000 $137,500 $165,000 $184,500 $198,000 $240,000 $232,000

50th $100,000 $110,000 $130,000 $150,000 $149,000 $190,000 $160,000

25th $87,500 $95,000 $104,000 $121,500 $118,500 $133,484 $110,250

10th $80,372 $72,900 $85,000 $83,471 $83,300 $91,872 $90,914

3

Welch t-tests were used in cases where group sizes and/or group variances were unequal. The Welch t-test estimates

degrees of freedom using a formula that includes group variance divided by group size, leading to the potential for estimated

degrees of freedom to include decimal places.

Page 7 Results

Table 2. Base Salary by Years Since Master’s Degree

Years Since Degree

< 2

2-4

5-9

10-14

15-19

20-24

n

17

72

79

31

20

12

Median

$65,000

$87,500

$99,174

$120,750

$153,636

$155,000

Mean

$65,668

$88,273

$107,313

$123,899

$167,336

$172,250

Percentile

90th

$90,055

$119,000

$151,000

$165,000

$209,650

$232,600

75th

$72,500

$102,025

$121,114

$143,500

$178,000

$205,000

50th

$65,000

$87,500

$99,174

$120,750

$153,636

$155,000

25th

$50,000

$72,875

$87,000

$102,000

$130,000

$129,500

10th

$37,017

$52,800

$72,400

$80,000

$109,500

$116,300

We also examined whether this unusual pattern in doctorate salary by years since degree was found when

separating practitioners and academics. As shown in Table 3, median income for those in academia at 15-

to-19 years out from their degree was slightly lower than for academics 10-to-14 years from their degree,

while for practitioners this cohort exhibited the expected increase in income from the 10-to-14-years

practitioner cohort. The median salary at the doctorate level for academics 25 or more years out from their

degree was $118,400 while the median salary for practitioner doctorate holders in this cohort was $206,138.

However, even accounting for career field, the median salary for doctorate-level I-Os did not continue to

increase after around 20-to-24 years of experience. For doctorate-holding I-Os in academia, median salary

at 25-or-more years is much lower than for those at 20-to-24 years since degree. Salaries for those in

academia are explored further in a subsequent section of the report.

Table 3. Base Salary by Years Since Doctorate Degree for Practice and Academia

Years Since Degree for Practitioners

< 2 2-4 5-9 10-14 15-19 20-24 25+

n 20 86 107 53 39 32 50

Median

$100,520 $120,000 $149,800 $155,000 $171,858 $207,149 $206,138

Mean $107,068 $127,099 $159,371 $192,010 $202,008 $374,472 $220,796

Years Since Degree for Academics

< 2

2-4

5-9

10-14

15-19

20-24

25+

n

5 21 50 34 32 25 49

Median N/A $89,319 $101,666 $124,500 $121,294 $133,484 $118,400

Mean

N/A $86,808 $107,809 $130,626 $135,779 $156,037 $214,636

Page 8 Results

Salaries for master’s degree holders increase with years of experience (Table 4). The group size was

not sufficient to report salary information for master’s degree holders at 25 or more years since earning

their degree.

Table 4. Base Salary by Years Since Master’s Degree for Practitioners

Years Since Degree

< 2 2-4 5-9 10-14 15-19 20-24

n 17 71 76 31 20 11

Median $65,000 $88,000 $102,000 $120,750 $153,636 $160,000

Mean $65,668 $88,432 $109,488 $123,899 $167,336 $176,091

Across years since degree, median doctorate-level I-O salaries were higher than those of master’s-level I-

Os at all time points except for respondents who earned their degree 15-to-19 years ago (Figure 3). The

number of master’s-level I-Os at 25-or-more years since earning their degree was not sufficient to report

salary information. For each cohort up to and including 10-to-14 years since degree, median doctorate and

master’s level income rose at similar rates. The difference between doctorate and master’s degree holders

in median salaries when starting their careers may reflect differences in skill level or entry-level job

responsibilities for those graduating with a doctorate versus a master’s degree. Likewise, the ongoing

difference in pay over years since degree may be partly explained by greater skill and expertise

requirements in job roles for doctorate holders.

Figure 3. Median Income by Years Since Degree

$100,000

$110,000

$130,000

$150,000

$149,000

$190,000

$160,000

$65,000

$87,500

$99,174

$120,750

$153,636

$155,000

< 2 2-4 5-9 10-14 15-19 20-24 25+

Doctorate Master's

Page 9 Results

Certifications

Holding a license or professional credential may also impact income for I-Os. Many respondents reported

holding some type of certification or credential (n = 151). A greater percentage of master’s degree holders

held certifications (23%) than did doctorate-level respondents (18%), although for both master’s level and

doctoral level respondents, this is a percentage increase from the 2019 report (21% and 12%, respectively).

Table 5. Base Salary by Type of Certification

Doctorate

HR related

Certification

Coaching

Certification

Other

Certification

No Professional

Certification

n 39 12 49 554

Median $160,000 $136,638 $165,000 $135,000

Mean $184,825 $157,754 $250,242 $159,155

Master’s

HR related

Certification

Coaching

Certification

Other

Certification

No Professional

Certification

n 19 7 25 180

Median $116,400 N/A $96,000 $96,950

Mean $128,528 N/A $94,786 $105,663

Note. The number of master’s-level respondents with a coaching certification was insufficient for reporting

salary information.

For respondents with a master’s degree, the median income for those with some type of certification was

$106,694 (n = 51) and for those without any certification (n = 181) was $96,950 (n.s.). For doctorate holders,

those with at least one certification (n = 125) earned a median salary of $156,000 while the median salary

for those with no certification (n = 560) was $135,000 (n.s.). Figure 4 shows the median salary by type of

certification for both doctorate-level and master’s-level I-Os.

Page 10 Results

Figure 4. Median Salary by Certification Type by Degree Level

Note. Median salary for master’s degree holders with a coaching certification is not reported due to insufficient

group size.

There were too few master’s-level respondents with a coaching certification to include in the results. For

doctorate-level I-Os, having a certification other than HR-related or coaching was associated with a higher

salary than having no certification (F (3, 651) = 3.94, p < .05). Except for this comparison, salaries within

degree levels for those with a certification were not significantly higher than for those without.

“Professional certifications were associated

with increased income for I-Os. Depending on

the type of certification, doctorate-level salaries

were up to 15.5% higher and master’s-level

salaries were up to 10% higher.”

$160,000

$136,638

$165,000

$135,000

$116,400

$96,000

$96,950

HR related certification Coaching certification Other certification No professional certification

Doctorate Master's

Page 11 Results

Career Type

The skills and expertise of I-O psychologists are of

value to organizations in many employment sectors.

For this report, we grouped employment sectors into

five categories: university or college, private for-profit,

nonprofit, government, and self-employed consulting.

The majority of survey respondents reported working

in private for-profit organizations (56%), with the next

largest percentage working in academia (28%). Most

academics hold a doctorate degree, with only 2.2% of

master’s-level I-Os employed in academia. Figures 5

and 6 show the percentage of doctorate holders and

master’s degree holders in each employment sector.

Income can vary greatly by employment sector.

Among practitioners, self-employed consultants

reported substantially higher salaries than those in

other sectors, although this difference did not meet

statistical significance. Doctorate-level practitioner income is significantly greater than income for doctorate-

level academics (t(593.2) = 2.87, p > .05). More specifically, as Table 6 shows, doctorate-level private-sector

for-profit income was significantly higher than income for academics (t(548.4) = 2.74, p < .01). For those

with a master’s degree (Table 7), although the median salary for I-Os working in nonprofit organizations

was lower than for those working in government or for-profit organizations, the difference was not

statistically significant.

Figure 5. Doctorate-Level I-Os in Each Employment Sector

38%

48.5%

5.5%

5.5%

2.2%

University or College

Private Sector- For-Profit Organization

Not for Profit Organization

Government

Self-employed, consulting

Page 12 Results

Figure 6. Master's-Level I-Os in Each Employment Sector

Table 6. Base Salary by Employment Sector for Doctorate-level I-Os

Doctorate-Level Base Salary

For-Profit Non-Profit Government

Self-employed

Consulting

Academia

n

356

41

41

16

274

Median

$150,000 $147,000 $127,000 $250,000 $111,438

Mean

$181,025 $157,308 $174,473 $265,689 $141,916

Table 7. Base Salary by Employment Sector for Master’s-level I-Os

Master’s-Level Base Salary

For-Profit

Non-Profit

Government

n

217

19

28

Median

$101,700

$80,000

$113,500

Mean

$110,182

$92,844

$116,226

2.2%

79.7%

6.9%

9.8%

1.1%

University or College

Private Sector- For-Profit Organization

Not for Profit Organization

Government

Self-employed, consulting

Page 13 Results

Applied Employment

Industry

Salary varies by industry for both doctorate-level I-Os and master’s-level I-Os. The highest median base

salary for those with a doctorate degree was in the healthcare industry (Figure 7), although I-O salaries

between industries did not significantly differ. This is likely in part due to small group sizes and substantial

I-O salary variance within industries.

Figure 7. Doctorate - Median Base Salary by Industry

Note. Numbers in parentheses in Y-axis labels indicate respondent N for each listed industry.

For master’s degree holders (Figure 8), I-Os in the technology industry earned the highest median base

salary (F(3, 147) = 4.1, p < .01). Technology salaries were significantly higher than consulting organization

salaries (p < .05) or healthcare salaries (p < .05) for I-Os with a master’s degree.

Figure 8. Master's - Median Base Salary by Industry

Note. Numbers in parentheses in Y-axis labels indicate respondent N for each listed industry.

$132,000

$137,000

$141,000

$147,163

$148,604

$167,250

$175,000

$180,000

Retail (13)

Consumer Products (13)

Banking, Finance, or Insurance (17)

Consulting Org (136)

Manufacturing (28)

Technology (88)

Information Technology/Computers (10)

Healthcare (20)

$88,000

$95,500

$103,459

$105,819

$121,729

Healthcare (15)

Consulting Org (76)

Banking, Finance, or Insurance (19)

Manufacturing (16)

Technology (41)

Page 14 Results

Job Title

In addition to degree level, years of experience, and job sector or industry, I-O salaries vary by job title. Of

course, job title is often related to years of experience. As I-Os gain experience, they may move into

positions with greater responsibility at a higher salary. Table 8 gives median, mean, and salary percentiles

across job titles for doctorate-level practitioners. Compared to the 2019 report, median salaries were higher

for every job title. This may be partly due to members in the same position receiving pay raises, although the

increase from 2019 for those at the entry-level likely indicates a general upward shift in salaries for

practitioner I-Os.

While median salaries incremented upward for increasing levels of responsibility, the mean doctoral-level

salary for vice president was higher than for senior vice president (n.s.). Also, the range of salaries for vice

presidents was greater than for senior vice presidents. As found in previous reports, the comparatively lower

mean salary for senior vice presidents is possibly due to the smaller size of organizations in which they tend

to work compared with vice presidents. About half of senior vice presidents work in companies with fewer

than 300 employees and 25% work in companies with fewer than 100 employees, while nearly 78% of vice

presidents work in companies with more than 300 employees (and more than a third work in companies with

more than 3,000 employees).

Table 8. Practitioner Base Salary by Job Title for Doctorate Degree Holders

Entry-

level

Consultant

Senior

Consultant

Direct

Supervisor

HR

Mgr.

Non-HR

Mgr.

Vice

President

Senior

Vice

President

n 14 78 140 49 91 29 27 12

Median $88,050 $116,500 $144,500 $151,928 $173,000 $160,000 $220,000 $239,000

Mean $86,431 $123,986 $158,566 $154,043 $192,685 $164,874 $318,200 $243,333

Percentile

90th $103,861 $150,637 $221,800 $191,400 $235,000 $231,200 $433,000 $297,300

75th $92,875 $139,250 $170,090 $170,000 $212,500 $197,000 $257,500 $255,750

50th $88,050 $116,500 $144,500 $151,928 $173,000 $160,000 $220,000 $239,000

25th $73,370 $100,150 $120,750 $131,000 $139,000 $140,544 $190,000 $215,750

10th $67,100 $90,140 $104,000 $111,016 $120,000 $90,000 $179,000 $186,500

Note. HR Mgr. = manager/director of human resources. Non-HR Mgr. = manager/director of other than human

resources unit.

Page 15 Results

Master’s-level practitioner salaries also rose with increased job responsibility (Table 9), although median and

mean salaries for master’s-level I-Os were lower than their doctorate-level counterparts for all job titles. For

master’s-level respondents, we combined the roles of vice president and senior vice president to increase

group size for reporting purposes. We examined the organization size for master’s-level vice presidents and

senior vice presidents compared with doctorate holders. Organization size for master’s degree holders in

these roles was similar to that of doctorate-level senior vice presidents, with 55% of master’s degree holders

at this job level working in organizations with fewer than 300 employees.

Table 9. Practitioner Base Salary by Job Title for Master’s Degree Holders

Entry-level Consultant

Senior

Consultant

Direct

Supervisor

HR

Mgr.

VP or

Senior VP

n 25 99 61 14 46 11

Median $61,800 $90,000 $113,000 $118,364 $127,000 $200,000

Mean $61,535 $93,006 $119,442 $118,156 $134,038 $200,818

Percentile

90th $89,250 $117,960 $160,000 $143,205 $206,750 $230,000

75th $79,000 $102,500 $142,000 $130,000 $168,750 $220,000

50th $61,800 $90,000 $113,000 $118,364 $127,000 $200,000

25th $43,500 $75,000 $97,500 $100,650 $99,380 $159,500

10th $28,100 $65,244 $79,799 $95,625 $67,500 $105,000

Note. VP or SVP = vice president or senior vice president. HR Mgr. = manager/director of human resources.

“The highest median base salary for

those with a doctorate degree was in the

healthcare industry, and the highest median

base salary for those with a master’s

degree was in the technology industry.”

Page 16 Results

Academic Employment

As with I-O practitioner workplaces, several

institutional characteristics contribute to academic

salaries. Private and public institutions have

different primary funding sources, with public

colleges and universities largely relying on state

government funding and private institutions relying

more on tuition and private endowments for their

funding. These funding differences can impact

academic salaries. Table 10 shows that academic

respondents reported higher median and mean

salaries working in public institutions than in private.

Table 10. Doctorate-Level Base Salary by Institution Type

Public Private

n 199 69

Median $115,000 $96,000

Mean $132,744 $114,485

Another institutional characteristic affecting academic salary is the degree-granting level of the college or

university. Figure 9 shows median salary by degree-granting level for public and private institutions. Salaries

for doctorate-granting institutions were highest for both public and private universities. For public institutions,

differences between degree-granting levels were not statistically significant; however, academics at private

doctorate-granting universities earned significantly more than their counterparts at master’s-granting schools

(t(63.9) = -3.69, p < .01).

“Academics in business schools or

departments earned significantly more

than those in psychology departments.”

Page 17 Results

Figure 9. Median Salary by Degree-granting Level by Institution Type

Note. Median salary for academics working at a private baccalaureate institution is not reported due to insufficient

group size.

A third factor affecting academics’ income is the department in which they work. We asked academic

respondents what department they worked in at their college or university. Although some respondents

worked in industrial relations (n = 5) and education departments (n = 2), these group sizes were too small to

include as stand-alone categories, so we grouped them into a category labeled ‘other’ with academics who

reported working in a wide variety of departments, such as communication, medicine, professional studies,

and leadership, among others. Table 11 shows median and mean salary by academic department. As in

previous reports, academics in business schools or departments earned significantly more than those in

psychology departments (t(101.5) = -2.89, p < .01). Although, business school academics also earned more

than those in administrative roles or in departments other than psychology, the differences were not

statistically significant.

Table 11. Doctorate-Level Base Salary by Academic Department

Psychology Business Administrative Other

n 136 99 11 26

Median $92,000 $144,000 $114,000 $122,794

Mean $106,184 $192,783 $127,282 $144,572

Next, we compared salaries for different levels of professorship in academia. Given the difference in income

between academics in psychology departments and those in business schools or departments, we

examined salary by job title for professors in business schools and in psychology departments separately

(Figure 10). The number of distinguished or chaired professors in business schools in the sample (n = 6)

was not sufficient for reporting or analysis. Mean business school salary for associate professors was

significantly higher than for assistant professors (F(2, 74) = 5.97, p < .01), but salary differences between full

$83,750

$104,167

$90,568

$103,511

$128,248

Baccalaureate Institution Master's Institution Doctoral Institution

Private Public

Page 18 Results

professors and either associate or assistant professors were not statistically significant. There were

significant differences in salary for academics teaching in psychology departments (F(3, 115) = 41.6, p <

.001). Distinguished or chaired professors in psychology earned significantly more than all other types of

professor (p < .001), and full professors earned significantly more than either associate (p < .05) or assistant

professors (p < .01). However, even though median and mean salary for associate professors was higher

than for assistant professors, this difference did not reach the threshold of statistical significance.

Figure 10. Doctorate-Level Median Base Salary by Professor Type and Department

Note. Median salary for Distinguished/Chaired Professor in Business Departments is not reported due to

insufficient group size.

$129,000

$175,930

$143,118

$82,620

$87,179

$107,016

$191,500

Assistant Professor Associate Professor Full Professor Distinguished/Chaired

Professor

Business Department Psychology Department

Page 19 Results

Geographic Location

We asked members to provide the first three digits

of their workplace zip code, and then matched

these to U.S. cities and states. We then grouped

city/state data by metro area

4

. For those working in

Canada, we asked for the first three characters of

their postal code. Due to sample size restrictions,

we were not able to group Canadian I-Os by their

city or province. Both doctorate-level and master’s-

level I-Os working in the San Francisco Bay Area

had the highest median base salary (Tables 12 and

13), although when adjusted for cost of living

5

,

base salaries were highest for doctorate-level I-Os

in the Houston metro and for master’s-level I-Os in

the Chicago metro area. This is a change from the

2019 report, where adjusted median salary was

highest for doctorate holders in the Dallas metro

area and highest for master’s degree holders in the

Charlotte metro area. The percent of academic I-Os in a metro area was negatively correlated with the

median doctorate-level income for that area (r = -.44, p < .01). However, sample sizes are insufficient to

report salary by geographic location for practitioners and academics separately.

“Doctorate-level and master’s-level I-Os

working in the San Francisco Bay Area

had the highest median base salary.”

4

We used the Office and Management and Budget’s Metropolitan Statistical Areas 2015 bulletin to group cities by metro area.

5

To facilitate comparisons across reports, we used the same cost of living indices as were used in the 2019-20 report; the

Cost of Living Calculator from PayScale, Inc., at https://www.bestplaces.net/cost-of-living/, using the Washington D.C. metro

area as the referent.

Page 20 Results

Table 12. Doctorate-Level Base Salary by Metro Area

n Median Mean

Percent

Academic

Adjusted

Median

San Francisco metro

15

$196,000

$217,029

0%

$121,520

Manhattan metro

17

$185,000

$280,336

12%

$125,800

Los Angeles metro

11

$180,000

$191,665

27%

$154,800

Houston metro

18 $152,500 $172,770 33% $239,425

Minneapolis metro

17 $150,000 $157,283 18% $215,100

DC metro

68

$149,500

$175,587

6%

$149,500

Atlanta metro 17 $137,000 $185,709 29% $188,649

Chicago metro

27

$126,500

$154,547

44%

$177,353

Detroit metro

10 $122,288 $142,235 30% $207,644

Dallas - Fort Worth metro

17 $120,000 $141,892 0% $178,920

Portland metro

13

$120,000

$275,365

31%

$136,440

Tulsa metro

10

$113,500

$118,805

55%

$207,478

Other metro

64

$141,000

$145,318

42%

Not metro

16 $137,554 $145,594 50%

Canada

18 $106,121 $114,577 78%

Other countries

22

$122,250

$146,151

74%

Table 13. Master’s-Level Base Salary by Metro Area

n Median Mean Adjusted Median

San Francisco metro

10

$143,500

$131,390

$88,970

Manhattan metro

10

$106,500

$114,500

$72,420

DC metro

26

$99,000

$112,308

$99,000

Chicago metro

22

$95,500

$95,316

$133,891

Other metro

29

$97,000

$92,852

Page 21 Results

Bonuses

As in many professions, bonus pay is an important

part of the complete compensation package for I-O

psychologists. We asked members to provide the

types of bonuses they received in 2021 as well as

the total amount of their bonuses for the year.

Table 14 shows mean and median bonus amounts

as well as percentiles for those with a doctorate

degree and those with a master’s degree. Many

members reported receiving more than one type of

bonus, so the amounts presented in this table may

represent a combination of bonuses rather than

single bonuses.

Table 15 shows types of bonuses received as well

as the percentage of master’s-level and doctorate-

level I-Os that received them. Members reported

additional bonus types, but group sizes were too small to allow reporting. Not all organizations offer some

types of bonuses. For example, government employers and nonprofit companies do not offer stock options.

Types of bonuses I-Os receive are partly a function of the type of employer for whom they work. Individual

performance and organizational performance were by far the most common types of bonuses received by I-

Os at both the doctorate level and the master’s level.

Table 14. Bonuses for Doctorate and Master’s Degree Holders in 2021

Doctorate Master’s

n

370

169

Mean

$49,142 $22,768

Median $19,325 $10,000

Percentile

90th $105,335 $42,600

75th

$40,375 $20,000

50th $19,325 $10,000

25th

$7,575

$4,500

10th

$2,500

$1,948

Page 22 Results

Table 15. Types of Bonuses Received by Doctorate and Master’s Degree Holders in 2021

Bonus Type

Doctorate

Master’s

n

%

n

%

Individual performance 304 41% 140 51%

Organizational Performance 226 31% 118 43%

Group, department, or unit performance 91 12% 43 16%

Sign-on or recruiting bonus 28 4% 11 4%

Retention bonus 28 4% *

Exercising stock options 15 2% *

Special project 14 2% 10 4%

Other (please specify): 17 2% *

*N is too small to report.

For those who listed only one type of bonus, we report mean and median amounts by type of bonus (Table

16). The types of bonus with sufficient group size to report were individual performance bonuses,

organizational performance bonuses, and sign-on bonuses. Individual performance bonuses were slightly

larger than organizational performance bonuses, although the difference was not statistically significant.

Individual bonuses were significantly higher for doctorate-level I-Os than for master’s-level I-Os (t = 2.58,

df(119), p < .05). The difference between doctorate-level organizational performance bonuses and those for

master’s degree holders was not statistically significant. Sign-on bonuses for doctorates were double or

nearly double that of performance bonuses.

Table 16. Amount of bonus by type of bonus in 2021

Doctorate Master's

n Median Mean n Median Mean

Individual performance 95 $10,000 $27,703 31 $7,000 $10,363

Organizational performance 45 $8,000 $20,511 21 $6,000 $12,677

Sign-on or recruiting bonus 15 $18,000 $68,167 *

*N is too small to report.

Page 23 Results

Raises

Historically, I-O salaries have risen over the years.

This is, in part, due to organizations’ efforts to keep

up with the cost of living. However, I-Os can

increase their pay in many ways, including taking

on more responsibilities or receiving a promotion,

moving to a different organization, or receiving a

merit raise. We asked members whether they

received a raise in 2021 and if so, to report the

reason for the raise as well as the size of the raise

as a percentage of their base salary (Tables 17 and

18). In addition to the types of raises listed in the

tables, I-Os reported receiving raises from union

negotiations, changing employers, or lateral job

changes within the same organization; however, the

number of I-Os reporting these types of raises was

too small to report. The most common type of raise

for both doctorate-level and master’s-level I-Os was

given when working for the same employer at the

same job with the same responsibilities. This was

distinguished from a cost-of-living raise, which only 4% (n = 42) of I-Os reported receiving in 2021. It may be

that many employers factor in cost of living increases with merit raises.

Raises were highest (as a percent of salary) for both doctorate-level and master’s-level I-Os who received

a promotion from their current employer. Master’s-level raises were, across the board, slightly higher than

were doctorate-level raises, although given the differential in pay between master’s-level I-Os and

doctorate-level I-Os, the dollar increase for those with a master’s degree may not be as large as for those

with a doctorate.

Table 17. Doctorate-Level Raises as Percent of Salary

Cost of Living

Same Employer

with Promotion

Same Employer,

Same Job, More

Responsibilities

Same Employer,

Same Job, Same

Responsibilities

n

31 62 12 290

Median 2.5% 10.0% 9.0% 3.0%

Mean 2.8% 15.6% 9.3% 4.8%

Percentile

90th

7.4% 32.3% 17.4% 10.0%

75th 3.0% 19.0% 13.8% 5.0%

50th 2.5% 10.0% 9.0% 3.0%

25th

1.0% 7.5% 4.6% 2.5%

10th 1.0% 5.0% 3.6% 2.0%

Page 24 Results

Table 18. Master’s-Level Raises as Percent of Salary

Cost of Living

Same Employer

with Promotion

Same Employer,

Same Job, More

Responsibilities

Same Employer,

Same Job, Same

Responsibilities

n 11 32 12 90

Median 3.0% 13.0% 10.0% 4.0%

Mean 3.4% 17.0% 10.5% 5.8%

Percentile

90th 6.6% 36.3% 19.8% 10.5%

75th 5.0% 22.5% 12.0% 7.2%

50th 3.0% 13.0% 10.0% 4.0%

25th 2.8% 10.0% 8.0% 3.0%

10th 1.5% 6.2% 4.7% 2.5%

Page 25 Results

Benefits

Benefits are an important component of a full

compensation package, and a large majority of I-

Os reported receiving a broad range of

employer-sponsored benefits in 2021. Because

of the differing market demands, constraints, and

types of employment arrangements among

employment sectors, we examined benefits by

job sector. As in the 2019 report, we compared

benefits for doctorate holders with those offered

by employers of master’s degree holders.

However, because similar percentages of

doctorate-level I-Os and master’s-level I-Os work

in similar industries, with the exception of

academia, benefits were generally comparable

across degree level. We did not include those

with master’s degrees working in academia due

to small sample size. In the following sections,

we look at types of benefits available to I-Os through their employers and note differences among sectors

and among degree levels. Overall, the type of benefits offered to I-Os through their employers and the

percentage of employers offering such benefits is similar to results in the 2019 report. The benefits most

commonly offered by employers of I-O psychologists are in these four categories: retirement, health,

disability, and paid time off.

Retirement Benefits

Across sectors, a majority of I-Os were able to participate in defined contribution retirement plans, although

most government employees were also offered a separate pension plan (Figure 11). Retirement benefits

were nearly equally available to doctorate-level and master’s-level employees. As in past reports, a defined

contribution retirement plan and a defined benefit or pension plan were described as follows:

In a defined contribution retirement plan, the organization and the employee pay a set

amount of money or percentage of salary annually into a retirement account while the

employee works at the organization. However, the amount of money the employee will

actually receive upon retirement is not a fixed amount, is not known till the employee

retires, and fluctuates based on the performance of the investments held in the account.

A few examples of defined contribution plans are 401(k) for businesses, 403(b) for tax-

exempt organizations, and SEP IRA for self-employed individuals, small business owners,

and partnerships.

In a defined benefit retirement plan, an organization typically agrees to pay an employee

a set amount of their final salary after the employee retires. For example, a company may

pay retired employees 60% of the average of their last three years of salary. The amount

of retirement benefit is defined, rather than dependent on how money in an individual’s

retirement account, such as a 401k, increases or decreases.

Page 26 Results

Figure 11. Retirement Benefits by Job Sector

Defined Contribution Retirement Plan (e.g., 401k, 403b)

Defined Benefit or Pension Plan

Leave, Health, and Disability Insurance Benefits

Paid time off (PTO) is a common employer benefit across sectors, with the exception of academia. As

shown in Figure 12, only 35% of academic respondents reported being offered PTO. This may be due to the

more flexible work schedules of those who teach at the college or university level. When examining roles

within academia, 90% of administrative staff and 27% of professors reported receiving PTO. Parental leave

was most common in private sector organizations, and much less common in academia. For those working

in the non-profit sector, a larger percentage of doctoral-level employees (51%) than master’s-level

employees (37%) reported being offered this benefit.

88%

71%

76%

84%

95%

64%

87%

Private Sector

Academia

Government

Non-Profit

Doctorate

Master's

N/A

16%

71%

13%

17%

71%

23%

14%

Private Sector

Academia

Government

Non-Profit

Doctorate

Master's

N/A

Page 27 Results

Figure 12. Leave Benefits by Job Sector

Paid Time Off

Parental Leave

Health insurance was the most common benefit offered by employers across all sectors, with 89% of

respondents reporting receiving employer-sponsored health insurance. Figure 13 shows the percentage of

respondents in each sector who are offered health insurance, health savings or flexible spending accounts,

wellness benefits, dental insurance, and vision insurance. Overall, wellness benefits are less common than

other types of health insurance, and least common for those in academia. Health savings accounts/flexible

spending accounts, vision insurance, and dental insurance are quite common across employment sectors,

although again, somewhat less common for academics. Short- and long-term disability insurance are less

common across sectors than are most types of health insurance (Figure 14).

95%

98%

35%

94%

Private Sector

Academia

Government

Non-Profit

Doctorate

Master's

95%

100%

94%

N/A

37%

57%

57%

51%

54%

15%

63%

Private Sector

Academia

Government

Non-Profit

Doctorate

Master's

N/A

Page 28 Results

Figure 13. Health Insurance Benefits by Job Sector

Health Insurance

HSA / FSA

Wellness Benefits

Private Sector

Academia

Government

Non-Profit

Doctorate

Master's

88%

93%

87%

92%

95%

100%

92%

N/A

N/A

61%

63%

52%

75%

Doctorate

Master's

89%

79%

75%

Private Sector

Academia

Government

Non-Profit

Doctorate

Master's

53%

26%

45%

N/A

32%

32%

16%

45%

Private Sector

Academia

Government

Non-Profit

Page 29 Results

Vision Insurance

Wellness Benefits

Dental Insurance

Private Sector

Academia

Government

Non-Profit

Doctorate

Master's

80%

76%

62%

85%

89%

82%

86%

N/A

Doctorate

Master's

88%

83%

78%

88%

95%

96%

89%

N/A

Private Sector

Academia

Government

Non-Profit

Page 30 Results

Figure 14. Disability Benefits by Job Sector

Short-term Disability

Long-term Disability

Life Insurance / AD&D

Doctorate

Master's

76%

39%

42%

75%

Private Sector

Academia

Government

Non-Profit

79%

43%

77%

N/A

Doctorate

Master's

76%

46%

51%

72%

Private Sector

Academia

Government

Non-Profit

89%

57%

78%

N/A

Doctorate

Master's

73%

83%

69%

85%

84%

93%

86%

Private Sector

Academia

Government

Non-Profit

N/A

Page 31 Results

Professional Development and Education Benefits

Additional benefits beyond retirement, health, and leave are of value to employees and organizations offer

them to attract and retain talent. As shown in Figure 15, overall, about half of I-Os reported their employers

offer professional development funds and conference travel funding, although this varied by sector. Tuition

assistance was less common. While relatively rare, research funding was more common in academia (35%)

than in other sectors.

Figure 15. Professional Development and Education Benefits by Job Sector

Professional Development Funds

Tuition Assistance

Doctorate

Master's

63%

41%

43%

45%

Private Sector

Academia

Government

Non-Profit

63%

54%

44%

N/A

Doctorate

Master's

46%

34%

27%

26%

Private Sector

Academia

Government

Non-Profit

47%

43%

33%

N/A

Page 32 Results

Conference Travel Funding

Research Funding / Start-up Budget

Other Benefits

STOCK OPTIONS, PROFIT SHARING, AND BONUS PAY

As expected, stock options and profit sharing are rare in all but the private sector, with about half of private

sector employers offering these benefits to their I-O employees (Figure 16). While more common in private

for-profit companies than in other sectors, bonus pay was fairly common in government and non-profit

organizations and very rare in academia.

Doctorate

Master's

73%

66%

62%

62%

Private Sector

Academia

Government

Non-Profit

42%

61%

44%

N/A

Doctorate

Master's

15%

5%

35%

2%

11%

4%

1%

Private Sector

Academia

Government

Non-Profit

N/A

Page 33 Results

ADDITIONAL BENEFITS

Commuter benefits or technology stipends are offered by less than half of employers and are quite rare in

academia (Figure 17). These types of benefits may become more common if the current remote work trend

continues. Other types of benefits offered by employers included pet insurance, 529 plans, legal insurance,

employee discounts, employee assistance programs, fertility benefits, and others; however, these were

extremely rare. We grouped these under ‘Other Benefits’ in Figure 21.

Figure 16. Stock Options, Profit Sharing, and Bonus Pay by Job Sector

Stock Options or Profit Sharing

Bonus Pay

Doctorate

Master's

5%

0%

1%

58%

Private Sector

Academia

Government

Non-Profit

5%

0%

41%

N/A

Doctorate

Master's

44%

34%

10%

79%

Private Sector

Academia

Government

Non-Profit

47%

37%

68%

N/A

Page 34 Results

Figure 17. Other Benefits by Job Sector

Commuter Benefits

Technology Stipend

Other Benefits

Doctorate

Master's

39%

46%

4%

25%

Private Sector

Academia

Government

Non-Profit

26%

36%

23%

N/A

Doctorate

Master's

17%

10%

14%

43%

Private Sector

Academia

Government

Non-Profit

32%

14%

39%

N/A

Doctorate

Master's

10%

0%

4%

8%

Private Sector

Academia

Government

Non-Profit

0%

0%

6%

N/A

Page 35 Results

Supplemental Income

Many opportunities exist to supplement salaries for those working in academia or as practitioners. Academic

I-Os more often engage in activities to earn supplemental income, and engage in a wider variety of such

activities, than do practitioner I-Os. Tables 19 and 20 show sources of supplemental income and amounts

earned from each source for academics and practitioners. Academics more often engage in additional

teaching than other types of work to supplement their income, with 37% of academics reporting this as a

source of additional income. A second common source of income for academics is through consulting

(30%). Engaging in external research is a less common source of additional income in academia, although

the median income earned from it is higher than from other types of additional work. Practitioners engage in

fewer activities to generate supplemental income and at a lower rate than do academics. The two most

common sources of supplemental income for practitioners were writing (9.5%) or speaking engagements

(6%). Of these, speaking engagements bring in the highest median supplemental income.

Table 19. Academic Supplemental Income by Source

Additional

Teaching

Consulting

Speaking

Writing

Textbook

Review

Internal

Research

Grants

External

Research

Grants

Other:

Administration

n

107

87

30

34

14

52

34

11

Median

$9,669

$8,000

$1,000

$1,000

$325

$8,000

$15,500

$7,500

Mean

$13,242

$31,770

$3,711

$2,415

$450

$15,520

$20,855

$8,109

Percentile

90th

$28,400

$68,400

$9,500

$8,000

$1,000

$48,500

$48,500

$16,597

75th

$16,000

$29,000

$3,000

$2,125

$850

$20,000

$20,500

$14,000

50th

$9,669

$8,000

$1,000

$1,000

$325

$8,000

$15,500

$7,500

25th

$5,000

$3,000

$338

$500

$188

$4,500

$5,863

$3,000

10th

$3,000

$1,740

$200

$90

$100

$1,685

$2,400

$1,000

Note. ‘Other: Administration’ includes administrative work, additional advising role, program director, department

head supplement, associate chair stipend, or associate dean stipend.

Table 20. Practitioner Supplemental Income by Source

Speaking

Writing

Textbook Review

n

46

70

14

Median

$8,000

$5,500

$450

Mean

$9,902

$19,150

$7,298

Percentile

90th

$21,196

$50,000

$42,500

75th

$15,250

$20,000

$3,750

50th

$8,000

$5,500

$450

25th

$3,500

$2,000

$238

10th

$2,350

$1,000

$110

Page 36 Results

The Impact of COVID-19

Unlike previous periods of time between SIOP income and employment surveys, the last two years saw

major disruptions in the workforce worldwide. The COVID-19 pandemic did not impact income for the

majority of I-Os, but its effects were felt to varying degrees across job sectors, in practice and academia,

and across demographic categories. The brunt of COVID-19’s impact on income for I-Os was felt in 2020,

with 2021 seeing a lessening of those effects.

COVID-19 Impact on Remote Work Arrangements

Due to the pandemic, work arrangements changed dramatically in 2020 for both practitioner and academic I-

Os. As in past surveys, we asked members about the amount of time they worked remotely or in person at

an office or place of business. However, in the current survey, we asked members to report their work

arrangements for three timepoints: in 2020 before COVID-19, in 2020 during COVID-19, and in 2021. Figure

18 shows overall percentages of I-Os with remote, hybrid, and in-person work arrangements at these three

timepoints. “Remote” are those working 100% of the time somewhere other than at the office; “Hybrid” are

those working at least some percentage of time at the office and some percentage of time not at the office;

and “In Person” are those working 100% of time in the office. At the beginning of 2020 before the pandemic,

a majority of I-Os had hybrid arrangements (59%) – working part of the time at home and part of the time in

the office – while 17% worked fully remotely. During the height of COVID-19 in 2020, the percentage of I-Os

working fully remotely dramatically increased to 74%. In 2021, the percentage of I-Os working fully remotely

dropped to 42%; still much higher than the 17% of I-Os working fully remotely before the pandemic.

However, the percentage of those working in-person in 2021 remained at the 2% as was seen during the

latter part of 2020. These changes reflected trends in work arrangement throughout the U.S. workforce in

2020 and into 2021

6

.

Figure 18. Work Arrangements in 2020 and 2021

Due to the differences in work schedules and job demands between I-O practitioners and academics, we

examined work arrangements for these two groups separately. Figure 19 shows work arrangements at the

three timepoints for practitioners. Because practitioners made up the majority of the sample, these trends

are similar to those found in the overall sample.

6

Pew Research Center reported 71% of workers who could perform their jobs from home worked remotely all or most of the

time by October 2020. By January 2021, this had decreased to 59%. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/social-

trends/2022/02/16/covid-19-pandemic-continues-to-reshape-work-in-america/.

17%

74%

42%

59%

23%

56%

25%

2%

2%

2020 Before COVID 2020 During COVID In 2021

Remote Hybrid In Person

Page 37 Results

Figure 19. Practitioner Work Arrangements in 2020 and 2021

Comparing I-Os in academia to those working as practitioners, a greater percentage of academics had

hybrid work arrangements before the pandemic, during the pandemic, and in 2021 than did their practitioner

counterparts. Figure 20 shows work arrangements for academics across the three time points. Traditionally,

academic work schedules have a great amount of scheduling flexibility, allowing professors and instructors

to do much of their work away from campus except when teaching or advising – to the extent these activities

are not done online. However, during the pandemic in 2020, only 56% of academics switched to fully remote

work compared to 81% of practitioners. This may have been due to the ongoing need for some academics

to teach in-person classes in the 2020 fall term. In 2021, the percentage of academic I-Os working fully

remotely dropped nearly two-thirds from mid-pandemic 2020 levels. In keeping with the 2021 trend for

practitioners, academic I-Os remained either fully remote or in hybrid working arrangements and did not

return to the same level of in-person work arrangements as seen before the pandemic.

Figure 20. Academic Work Arrangements in 2020 and 2021

22%

81%

69%

51%

16%

29%

27%

3%

2%

2020 Before COVID 2020 During COVID In 2021

Remote Hybrid In Person

2%

56%

20%

78%

43%

78%

20%

1%

2%

2020 Before COVID 2020 During COVID In 2021

Remote Hybrid In Person

Page 38 Results

When comparing salaries across the three different work arrangements, we examined doctorate-level and

master’s-level salaries separately. While the median salary for doctorate-level I-Os working remotely was

higher than for those with hybrid work arrangements or working in person across all time points, these

differences were not statistically significant. For master’s-level I-O’s, before the pandemic those with hybrid

work arrangements earned significantly more than those working in person (F(2, 270) = 4.99, p < .01).

As discussed in a previous section of this report, salaries vary by geographic location. These location-based

pay differences are most often influenced by the location of the company or its offices rather than the

location of an employee. However, some companies adjust pay for remote employees to align with the

location in which the employee lives. For the majority of I-Os, 2021 salaries were not impacted by changes

in work location due to remote work arrangements (Figure 21). If employees who shifted from hybrid to fully

remote work arrangements during the pandemic remain fully remote or choose to move to a different area

from where their workplace is located, companies may change their pay policies. It may be too soon to tell

what policies companies will adopt in the long term for remote work or location-based pay adjustments in the

years after the pandemic.

Figure 21. Remote Work Location During COVID-19 Impact on Pay

“For the majority of I-Os, 2021 salaries were

not impacted by changes in work location

due to remote work arrangements.”

88%

2% 1%

5%

2%

90%

1% 2%

4%

2%

Did not impact

my pay

Reduced

my pay

Increased

my pay

Don't know Not remote

in 2020

2020 2021

Page 39 Results

COVID-19 Impact on Employment

IMPACT ON EMPLOYMENT BY JOB SECTOR

The effects of the pandemic on income were felt more severely by I-Os in some job sectors than in others.

Figures 22 and 23 show the impact of the pandemic on job loss or income changes in 2020 and in 2021. I-

Os working in government reported the least disruption to work hours or income in both 2020 and 2021.

More than a quarter of self-employed I-Os experienced involuntary job loss in 2020, with nearly a third

reporting other income changes (e.g., salary, bonus, or benefit reduction) that year. These effects for self-

employed I-Os were lessened in 2021, although self-employed I-Os were still impacted to a greater degree

than were I-Os working in other sectors. As a comparison, a survey of U.S. households in August 2020

reported that 15% of adults had lost their jobs or been laid off due to COVID-19

7

, with the hardest hit

industries being retail, entertainment, and service

8

. Workers who could work from home may have been

more likely to continue working during the pandemic. As discussed in an earlier section of this report, I-Os

were generally able to make the shift from in-person or hybrid work arrangements to fully remote

arrangements when needed.

Figure 22. COVID-19 Impact on Income in 2020 by Job Sector

Figure 23. COVID-19 Impact on Income in 2021 by Job Sector

7

As reported by Pew Research Center. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2020/09/24/economic-

fallout-from-covid-19-continues-to-hit-lower-income-americans-the-hardest/.

8

As reported by Business Insider on May 12, 2020. Retrieved from https://www.businessinsider.com/jobs-industries-careers-

hit-hardest-by-coronavirus-unemployment-data-2020-5.

7%

1%

24%

70%

2% 1%

22%

76%

3% 0% 4%

94%

3% 2%

25%

72%

26%

0%

32%

53%

Involuntary job loss/

reduced hours

Voluntary job loss/

reduced hours

Other income changes No impact

Private Sector Academia Government Non-Profit Self-Employed

1% 0%

10%

89%

1% 0%

12%

87%

0% 0% 1%

99%

0% 0%

13%

87%

16%

0%

21%

63%

Involuntary job loss/

reduced hours

Voluntary job loss/

reduced hours

Other income changes No impact

Private Sector Academia Government Non-Profit Self-Employed

Page 40 Results

IMPACT ON EMPLOYMENT FOR PRACTICE AND ACADEMIA

Figures 24 and 25 show how COVID-19 impacted employment and income for academics and for

practitioners. In 2020, a greater percentage of practitioners than academics experienced involuntary job

loss, although both groups reported similar incidence of voluntarily quitting/ reducing work hours or other

income changes. In 2021, incidence of job loss or income changes had decreased by about half for both

practitioners and academics. Most respondents who reported losing their jobs in 2020 were able to find

employment again in 2021.

Figure 24. COVID-19 Impact on Income in 2020 for Practice and Academia

Figure 25. COVID-19 Impact on Income in 2021 for Practice and Academia

7%

1%

22%

72%

2% 1%

22%

76%

Involuntary job loss/

reduced hours

Voluntary job loss/

reduced hours

Other income changes No impact

Practitioner Academic

1% 0%

10%

89%

1% 0% 12%

87%

Involuntary job loss/

reduced hours

Voluntary job loss/

reduced hours

Other income changes No impact

Practitioner Academic

Page 41 Results

IMPACT ON EMPLOYMENT BY GENDER

Men and women experienced similar levels of job loss and reduced work hours due to COVID-19 (Table 21).

However, in 2020 women experienced a significantly greater percentage of other types of income changes

due to the pandemic than did men (χ

2

(1, N =1,010) = 7.9, p < .01).

Table 21. Impact of COVID-19 on Income by Gender

Impact

2020

2021

Men

Women

Men

Women

Involuntary job loss/reduced hours

5%

6%

1%

2%

Voluntary job loss/reduced hours

1% 1% 0% 0%

Other income changes

18%

26%

10%

10%

No impact

76%

70%

88%

89%

IMPACT ON EMPLOYMENT BY RACE/ETHNICITY

In the sample, race and ethnicity groups other than white were too small to examine by type of income

change, so we compared COVID-related employment changes for those who identified as white and for

those who identified as other than white (including multi- or bi-racial). A slightly higher percentage of I-Os

identifying as other than white experienced other income changes due to the pandemic in both 2020 and

2021 (Table 22).

Table 22. Impact of COVID-19 on Income by Race/Ethnicity

Impact

2020

2021

White

Non-white

White

Non-white

Involuntary job loss/reduced hours

5% 6% 1% 1%

Voluntary job loss/reduced hours

1%

1%

0%

1%

Other income changes

21% 25% 10% 13%

No impact

74%

70%

89%

86%

Note. Race/ethnicity subgroup N’s were too small to analyze by category.

Page 42 Results

OTHER INCOME CHANGES DUE TO COVID-19

Looking closer at COVID-19’s impact on I-O income, we asked members to report the type of income

changes (other than job loss or reduction of hours) they experienced due to the pandemic (Figure 26). In

2020, the largest percentages reported a reduction in the amount of their bonus (8.9%) or a reduction in

salary (8.4%). The third largest income change during 2020 was a reduction in benefits (7%). In 2021, these

percentages decreased by about a third or more. Interestingly, a little more than 2% of I-Os experienced an

income increase due to the pandemic in 2020 and in 2021. It is unclear whether this is due to increased

work hours, incentive pay, or gaining new employment.

Figure 26. Other Income Changes Due to COVID-19

“In 2020, the most notable effects of the pandemic

on I-O income were a reduction in bonus amount

(8.9%) or a reduction in salary (8.4%).”

8.4%

8.9%

7.0%

0.4%

2.4%

0.1%

1.8%

3.2%

2.6%

0.3%

2.2%

0.0%

Salary reduction Bonus reduction Benefit reduction Location pay

reduction

Income increase Other

2020 2021

Page 43 Results

OTHER INCOME CHANGES BY JOB SECTOR