© 2013 International Monetary Fund

IMF Country Report No. 13/348

ITALY

TECHNICAL NOTE ON THE FINANCIAL SITUATION OF

ITALIAN HOUSEHOLDS AND NON-FINANCIAL

CORPORATIONS AND RISKS TO THE BANKING SYSTEM

This Technical Note on the Financial Situation of Italian Households and Non-Financial

Corporations and Risks to the Banking System on Italy was prepared by a staff team of the

International Monetary Fund as background documentation for the periodic consultation with

the member country. It is based on the information available at the time it was completed in

August 2013. The views expressed in this document are those of the staff team and do not

necessarily reflect the views of the government of Italy or the Executive Board of the IMF.

The publication policy for staff reports and other documents allows for the deletion of market-

sensitive information.

Copies of this report are available to the public from

International Monetary Fund Publication Services

PO Box 92780 Washington, D.C. 20090

Telephone: (202) 623-7430 Fax: (202) 623-7201

E-mail: [email protected]

Web: http://www.imf.org

Price: $18.00 per printed copy

2013 International Monetary Fund

Washington, D.C.

December, 2013

ITALY

FINANCIAL SECTOR ASSESSMENT PROGRAM

TECHNICAL NOTE

THE FINANCIAL SITUATION OF ITALIAN HOUSEHOLDS

AND NON-FINANCIAL CORPORATIONS AND RISKS TO THE

BANKING SYSTEM

Prepared By

Monetary and Capital Markets

Department

This Technical Note was prepared by IMF staff in the

context of the Financial Sector Assessment Program

in Country. It contains technical analysis and detailed

information underpinning the FSAP’s findings and

recommendations. Further information on the FSAP

can be found at:

http://www.imf.org/external/np/fsap/fssa.aspx.

August 2013

ITALY

2 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION AND MAIN FINDINGS ________________________________________________________ 4

THE ITALIAN HOUSEHOLD SECTOR ____________________________________________________________ 5

A. Household Balance Sheets _____________________________________________________________________ 5

B. The Housing Market ___________________________________________________________________________ 9

C. Financial Linkages _____________________________________________________________________________ 11

D. Sensitivity Analysis ____________________________________________________________________________ 16

THE ITALIAN NON-FINANCIAL SECTOR_______________________________________________________ 22

A. Non-Financial Corporate Balance Sheets _____________________________________________________ 22

B. Financial Linkages _____________________________________________________________________________ 24

C. Insolvency and Debt Restructuring ____________________________________________________________ 29

D. Sensitivity Analysis ____________________________________________________________________________ 32

E. Contingent Claims Analysis ___________________________________________________________________ 36

CONCLUDING REMARKS _______________________________________________________________________ 39

REFERENCES ____________________________________________________________________________________ 40

TABLES

1. Household Debt Burden (2010)_________________________________________________________________ 17

2. Sensitivity Analysis of Indebted Households____________________________________________________ 20

3. Firms’ Ratio of Interest Expense to Gross Operating Income___________________________________ 33

4. Ratio of Interest Expense to Gross Operating Profits by Firm Size (2011)______________________ 34

5. Ratio of Interest Expense to Gross Operating Profits by Firm Size (2011)______________________ 35

FIGURES

1. Household Debt and Wealth_____________________________________________________________________ 8

2. The Housing Market____________________________________________________________________________ 10

3. Households’ Financial Conditions_______________________________________________________________ 14

4. Italian Household: Baseline Debt Vulnerability__________________________________________________18

5. Italian Household: Sensitivity Analysis__________________________________________________________ 21

6. Corporate Leverage, Funding Sources, and Profitability________________________________________ 25

7. Firms’ Financial Conditions______________________________________________________________________28

8. The Financial Situation of Italian Firms__________________________________________________________ 34

9. Sensitivity Analysis for Italian Firms_____________________________________________________________ 36

10. Contingent Claim Analysis for the Corporate Sector__________________________________________ 38

BOXES

1. Support Measures for Low-Income and Distressed Households________________________________15

ITALY

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 3

2. Measures to Support SME Financing___________________________________________________________ 27

3. The Legal Debt Restructuring Framework for Firms_____________________________________________31

ITALY

4 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

INTRODUCTION AND MAIN FINDINGS

1

1. This paper analyzes the vulnerabilities of the balance sheets of the Italian household

and corporate sector in order to assess the risk to the banking system. It takes a different

approach than the solvency and liquidity stress tests by assessing the financial soundness of the

main borrowers of the Italian banking system—households and the non-financial corporate sector—

and quantifying the potential impact from macroeconomic shocks. It relies on various sources of

information, including aggregate statistics and more granular information from household surveys

and corporate balance sheet databases.

2. The credit risk from Italian households is mitigated by their considerable net wealth.

Income has declined during the crisis, leading to tighter financial conditions for households,

especially for young and low-income groups, but low indebtedness, high levels of assets and

declining interest rates have protected households from wide-spread debt payment difficulties.

Sensitivity analysis show that further deterioration in economic conditions, through a fall in income

and higher interest rates, would reduce households’ debt repayment capacity, but their net wealth

position would continue to provide a considerable buffer, thereby dampening the potential risk

from the household sector to the banking system.

3. Real estate is the predominant source of collateral for loans, and severe strains in the

housing market could increase bank losses. The sharp drop in housing market activity reflects the

economic downturn, which has in turn put downward pressure on prices. Though housing prices are

not estimated to be substantially misaligned, continued weak activity is likely to put further

downward pressure on prices in the next few years. Sensitivity analysis shows that a moderate

decline in housing prices could be absorbed, partly due to the prudent loan-to-value ratios applied

to loans, but a more extreme shock, though not anticipated, would likely trigger credit losses for

banks and eat into provisioning coverage.

4. The financial situation of non-financial corporations, in particular SMEs, is fragile, as

evidenced by already high loan default rates. Even if the indebtedness of Italian firms is

moderate, leverage is high and has increased. About one-third of Italian firms, holding 45 percent of

the debt, are estimated to have interest payment coverage at vulnerable levels. SMEs have higher

than average leverage and lower interest payment coverage. Downside shocks to profits and interest

1

Prepared by Bergljot Bjørnson Barkbu. The note incorporates the following important contributions: Paolo Finaldi

Russo and Antonio de Socio (Bank of Italy) provided the sensitivity analysis for Italian firms, Dawn Chew (Legal

Department) drafted Box 3 on corporate bankruptcy law and parts of section III.C, and David Velazquez Romero

(European Department) carried out the Contingent Claims Analysis. I would also like to thank Marcello Bofondi, Laura

Bartiloro, Silvia Magri, Raffaella Pico and Francesco Zollino at the Bank of Italy for excellent input and suggestions,

and Zhengpeng Guo, Chen Kan, Piyaporn Nikki Sodsriwiboon, Amadou Sy, and Kenichi Ueda for very helpful

comments and advice.

ITALY

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 5

rates would increase credit risk stemming from the corporate sector though the additional strains

would likely be contained.

5. Continued strong policy action will be important to mitigate the impact of these

vulnerabilities, especially for firms. The government’s new initiative to pay part of its overdue

debt represents a crucial step to ease firms’ liquidity constraints. Continued efforts to increase

provisions−including by reducing fiscal disincentives and speed up the judicial process, strengthen

prudential considerations in collateral valuation and disclosure, and strengthened capital plans,

where needed, will be crucial to bolster confidence in banks, given the increase in non-performing

loans on their balance sheets. Also, further development of the private market for distressed assets

would help accelerate the disposal of non-performing loans and promote corporate restructuring.

Finally, with SMEs relying heavily on bank financing and suffering from tight credit conditions,

measures to expand SME financing, through more risk-based bank lending and opening up non-

bank financing channels, will be crucial to support their financial situation and the economic

recovery.

THE ITALIAN HOUSEHOLD SECTOR

A. Household Balance Sheets

6. Italian households’ debt level is low in an international perspective. Debt ratios more

than doubled during the low-interest period following the launch of the euro area; and have gone

from 33 percent of gross disposable income in 1998 to 74 percent December 2012 (Figure 1).

2

However, they remain well below those in other large economies such as France, Germany and the

United Kingdom, as well as the euro area average of 109 percent. Mortgages have been the key

source of the increase in household debt to banks (from a share of 50 percent of total bank loans

in 2003 to 60 percent in 2012), though reliance on mortgage financing continues to be low

compared to other countries.

7. The small degree of aggregate

indebtedness reflects a modest share of

indebted households. About 25 percent of

households had debt outstanding, compared

with 40 to 50 percent in other major euro area

countries, and more than 60 percent in the

United States and the United Kingdom. The

highest proportion of indebted households is

among those with higher income, with

41 percent of those in the highest quintile

having outstanding debt (see Bank of

2

Households include households and non-profit institutions servicing households.

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

Spain

Germany

France

Euro area

Italy

Proportion of Households with Debt

In percent

Source: ECB (2013).

ITALY

6 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Italy, 2012a). Among lower-income households (lowest quintile), only 17 percent have debt

outstanding. The median debt-to-income ratio for Italian indebted households is about 50 percent,

10 percentage points below the euro area average. Among indebted household, the average debt-

to-income ratio was 112 percent in 2010, though it is much higher for the lower-income households.

Also, given the high frequency of low values and progressively declining frequency for higher values,

the median debt-to-income ratio is much lower, at 46 percent. Debt-service, however, remains

moderate, at an average of 13 percent of income for indebted households in 2010, in line with the

euro area average.

8. The ratio of debt to disposable income has continued to increase during the crisis,

mainly due to stagnating income. The pace of growth of household debt slowed during the crisis,

reflecting tight credit conditions and low demand. Due to modest wage growth and high

unemployment, household disposable income has declined somewhat during 2008–12, and has

fallen by 13 percent in real terms (Figure 1). As a result, households’ debt-to-income burden has

continued to increase and the household savings rate dropped from 13 to 8 percent over the same

period as many lower-income households became unable to save (see Bartiloro and

Rampazzi, 2012).

9. Italian households have considerable wealth, as well as a buffer of liquid assets.

In 2010, Italian households’ net wealth and their ratio of liquid assets to income were above the

euro area average, while the debt-to-asset ratio was below. Net wealth represented about 8 times

disposable income, somewhat lower than in the U.K. (8¼), but higher than in France (7¾) and Japan

(5½). In the three years 2008–10, total net wealth increased by 1¾ percent; the growth was the

result of the flow of saving, which, though declining, more than offset the effects of the losses

caused by the fall in the value of financial assets.

10. Real assets, mostly housing, represent an important share of Italian households’

wealth. Home ownership in Italy is high, with 68 percent of households owning their house in 2010,

which is high compared to the euro area average (60 percent), Germany (44 percent) and France

(58 percent), though below Spain (83 percent). Real assets make up about two thirds of household

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

0

50

100

150

200

250

Spain

Italy

France

Euro area

Germany

Net Wealth and Debt-to-Assets

Median Net wealth (euros)

Debt-to-assets (in percent, rhs) 1/

Source: ECB (2013).

1/ For indebted households.

0

5

10

15

20

25

0

5

10

15

20

25

Germany

Italy

Euro area

France

Spain

Net Liquid Assets to Income

In percent

Source: ECB (2013).

ITALY

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 7

assets, and given relatively stable housing prices to date, have protected households from

fluctuations in asset prices during the financial crisis (see Bank of Italy, 2012b).

11. Financial wealth is concentrated in less risky assets such as deposits and bonds. The

value of Italian households’ financial assets as a ratio to disposable income (3½) has remained

broadly unchanged during the crisis. Some 92 percent of Italians hold financial assets, somewhat

below the euro area average (97 percent). The proportion of Italian households holding riskier assets

such as mutual funds (6 percent) and shares (5 percent) are about half that of the euro area average

(11 and 10 percent, respectively). Italian households’ financial portfolios contain a high proportion of

relatively low-risk assets, partly reflecting an ageing population, such as public and private bonds

(15 percent, compared to a 5 percent euro area average), and insurance and pension reserves. Over

the past decades, mostly due to a decline in asset prices, the value of investment in risky assets has

declined. Consequently, the share in financial assets of mutual funds and shares has been reduced

from 47 percent in 2000 to 25 percent in 2012. Ownership of the riskier assets is concentrated in

high-income households, with holders of mutual funds and shares predominantly belonging to the

two highest quintiles of the income distribution.

12. Low-income and young households have a small and declining share of the wealth,

making them more vulnerable to an economic downturn. Low-income and young households

have been more strongly hit by the decline in income and tight financial conditions during the crisis.

The richest 10 percent of households owned 46 percent of net wealth in 2010, up from 44 percent

in 2008. The net wealth of low-income households is 7 percent, which is low in a historical

perspective, and young households (with a head younger than 35 years) also hold a historically low

share of net wealth, at 5 percent.

ITALY

8 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Figure 1. Italy: Household Debt and Wealth

Household debt in Italy is low in an international

perspective

Mortgage financing has expanded, but remains below

levels in other advanced countries

Debt is less frequent among lower-income households,

though their average debt burden is more elevated

The economic downturn has reduced real disposable

income and savings

High real assets have contributed to a comfortable and

stable net wealth position

The share of riskier assets in financial assets has been

reduced, mostly reflecting declining asset values

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

180

200

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

180

200

1998

2000

2002

2004

2006

2008

2010

2012

Italy

Spain

France

Germany

Euro area

UK

Source: Eurostat, ISTAT and other national statistics agencies.

1/ Household includes households and non-profit institutions serving households

Household Debt to Gross Disposable Income, 1998-2012 1/

(In percent)

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

Italy

France

Germany

Euro area

Spain

UK

Household Debt to Banks to Gross Disposable Income,

2003, 2007 and 2012

(In percent)

Other

Mortgage

Consumer credit

Source: ECB, Eurostat.

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

1st

2nd

3rd

4th

5th

Total

Debt-to-Income Ratio and Indebted Households

(In percent, 2010)

Debt-to-income (mean)

Debt-to-income (median)

Households with debt (rhs)

Source: Bank of Italy. Quintiles

5

10

15

80

90

100

1999

2001

2003

2005

2007

2009

2011

2013

Household Disposable Income and Savings Rate

(In percent and index 2007=100)

Real disposable income

Savings rate (rhs)

Source: ISTAT.

-400

-200

0

200

400

600

800

1000

-400

-200

0

200

400

600

800

1000

1998

2008

2011

Household Net Wealth

(in percent of disposable income)

Liabilities

Financial assets

Real assets

Net wealth

Source: Bank of Italy.

0

20

40

60

80

100

0

20

40

60

80

100

2000

2007

2012

Household Financial Assets

(In percent of total)

Shares and mutual funds

Bonds

Reserves

Deposits

Source: Bank of Italy.

ITALY

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 9

B. The Housing Market

13. House price inflation in Italy has been in line with the euro area average. Over the last

decade, Italian housing prices increased on average by 4½ percent a year, about 2 percentage

points above HICP inflation, consistent with euro area trends (Figure 2). Indices of affordability show

that Italian house prices are somewhat above their long-term average, calculated as the average

since 1980, though less so than in countries where housing prices appear substantially overvalued.

The price-to-rent ratio was 2 percent above its historical average in 2012, while the price-to-income

ratio was 15 percent above. However, a study by the Bank of Italy—based on an econometric

analysis to determine a simultaneous equilibrium on the property market, the mortgage market and

the construction loan market—suggests that housing price developments have been in line with

fundamentals over the 25 years estimation period.

3

The current discrepancy between actual and

equilibrium housing prices is estimated to be less than one percentage point.

14. The weak economy and credit tightening have nevertheless translated into sharp

declines in housing market activity over the past year. High unemployment and declining real

incomes coupled with tightened bank lending standards have led to sharp falls in construction

investment and depressed house sales to half the peak level recorded in 2006. Housing transactions

started falling sharply in early 2012. Transactions declined by an annual rate of 30 percent in 2012

Q4, (Figure 2), though recovered to -14 percent in 2013 Q1, and the annual growth rate of

household mortgages turned negative in the beginning of 2013. The average time to sale has

reached more than 8 months. The majority of responding real estate agents in the April 2013

Housing Market Survey (Bank of Italy, 2013a) believes that the real estate tax put into effect in 2012

have contributed to weak activity and price declines.

15. Weak housing market activity and confidence have in turn exerted downward pressure

on prices. The Housing Market Survey shows that the number of transactions is being depressed by

a large price gap between sellers and buyers. The discount-to-ask price for sold houses reached

16 percent in 2013 Q1 (Figure 2). The official house price indices from ISTAT and the Bank of Italy

show that housing prices have fallen by almost 7 percent since their peak in 2011. The price fall is

larger for existing houses than new houses, for which prices just started falling in 2012 Q3. Price

indices from private sources show a larger price decrease, but have less comprehensive coverage

and do not capture the quality adjustment embedded in the official price index. In the next few

years, continued weak activity and tight lending conditions are likely to put further downward

pressure on prices. In this vein, most real estate agents surveyed by the Bank of Italy expect prices to

continue to fall in the next two years.

3

See Nobili and Zollino (2012).

ITALY

10 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Figure 2. Italy: The Housing Market

House prices in Italy have increased broadly in line with

the euro area average

House prices relative to income are somewhat above long-

term averages, but less so than in some countries

Transactions have fallen by almost 50 percent since their

peak in 2006, but the price adjustment has been limited

The discrepancy of official price indices with private

sources reflects quality adjustment and a larger sample

Real estate agents expect prices to continue to decline in

the short term

A large price gap between sellers’ and buyers’ prices is one

of the reasons for an increasing average time to sale

80

100

120

140

160

180

200

220

240

260

80

100

120

140

160

180

200

220

240

260

2000

2002

2004

2006

2008

2010

2012

Housing Prices

(Index, 2000=100)

Italy

France

Germany

Spain

Euro area

UK

Source: ECB, Halifax and Nationwide Building Society.

70

80

90

100

110

120

130

140

150

160

170

70

80

90

100

110

120

130

140

150

160

170

1997

1999

2001

2003

2005

2007

2009

2011

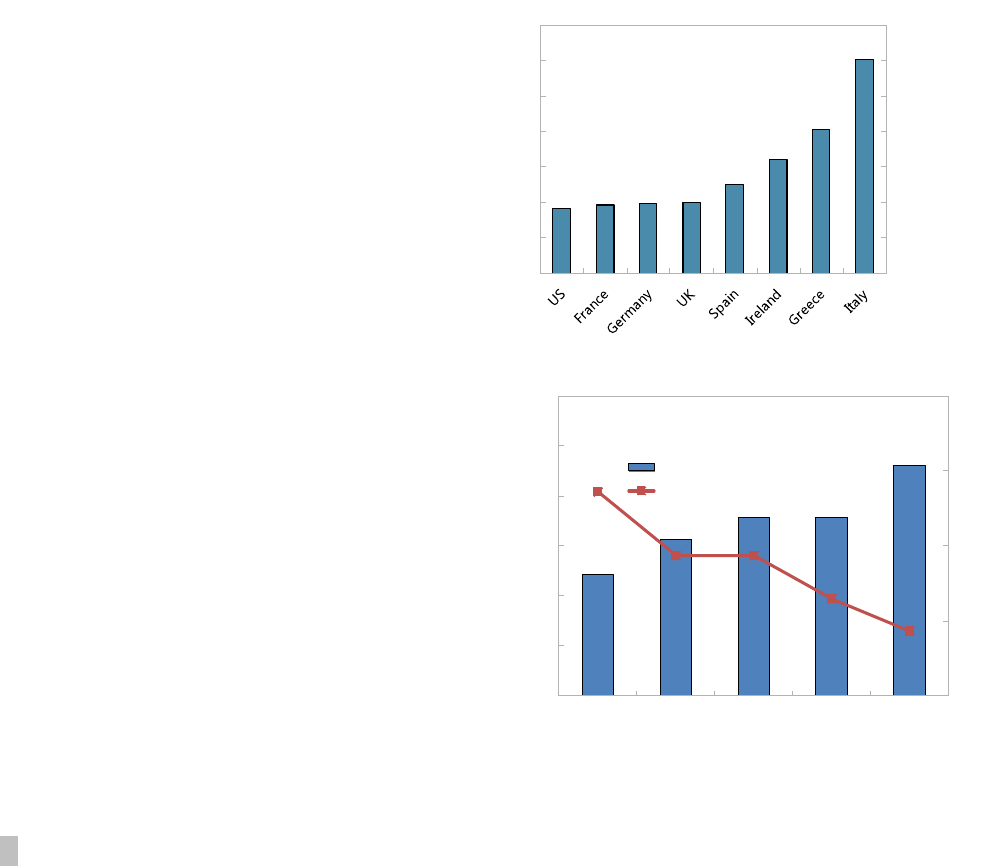

House Price-to-Income Ratios

(Index, long-term average = 100)

United States

Italy

United Kingdom

Ireland

Spain

Germany

France

Source: OECD.

60

80

100

120

140

60

80

100

120

140

2000

2002

2004

2006

2008

2010

2012

Italy: House Transactions and Real House Price

(Index, 2000=100)

Transactions

Real price

Source: Agenzia del Territorio, Bank of Italy, and ISTAT.

100

150

200

250

300

100

150

200

250

300

1990

1993

1996

1999

2002

2005

2008

2011

House Price Indices

(Index, 1990=100)

Bank of Italy

Nomisma

Source: Bank of Italy/ISTAT and Nomisma.

-80

-70

-60

-50

-40

-30

-20

-10

0

10

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

Expected Housing Prices Change 1/

Source: Bank of Italy.

1/ Balance of real estate agents' opinion indicating increase or

decrease in prices in the current quarter.

6

7

8

9

8

10

12

14

16

18

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

Price Discount and Sale Time

Time to sale (rhs, months)

Discount-to-ask price (percent)

Source: Bank of Italy.

ITALY

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 11

C. Financial Linkages

16. Bank credit to households has tightened since the onset of the crisis. Prior to the crisis,

during 2005–07, household debt granted by banks grew at an annual pace of more than 10 percent.

The growth slowed rapidly to 3 percent during 2008–09 and turned negative in late 2012, reaching

-1 percent in May 2013. The deceleration in 2012 affected all categories of loans, though mortgages

were particularly impacted, as new mortgages granted in 2012 roughly halved compared to 2011.

4

New consumer loans fell somewhat less, by 14 percent. The Bank Lending Survey (Bank of

Italy, 2013b) shows that both tighter credit standards by banks and lower loan demand by

households have contributed to the decline in credit. Currently, lower loan demand appears to be

the predominant factor, with households being affected by weak consumer confidence, lower

consumption and negative housing market prospects. Banks’ tight credit standards are explained by

negative prospects of the economy and the housing market for mortgages, and increasing concerns

about the credit worthiness of households for consumer credit.

17. Households’ relatively strong balance sheets have mitigated the impact of the crisis on

banks’ asset quality.

5

The stock of bad debt was 6 percent of total household debt in June 2013, of

which about 65 percent is secured with real assets (Figure 3). Default rates, given by the ratio of new

bad loans to total performing loans at the beginning of the period, have been stable at 1¼ percent

over 2010–13, relative to about ¾ percent in the pre-crisis years. But more leading indicators such

as past due and doubtful loans have recently seen increases, pointing to a possible further

deterioration in household credit quality. Past due household loans increased to 1.2 percent in June

2013, compared to 0.9 percent in December 2011, and doubtful household loans increased to

2.6 percent from 2.1 percent over the same period.

6

For both past due and doubtful loans, the

increases have been mainly for consumer credit and other loans (comprising overdrafts and

mortgages other than those used to purchase primary residences).

18. Loan-to-value (LTV) ratios for mortgages are prudent, and have decreased for new

mortgages. The low LTV ratios are, in part, a result of strict housing credit regulations and prudent

bank practices. According to the Housing Market Survey, LTV ratios on new mortgages have declined

from 69 percent at end-2008 to 56 percent in early 2013 (Figure 3). The average length of new

mortgage loans has remained broadly constant at 22 years over this period. For outstanding

mortgages, about two thirds had LTV ratios of between 50 to 80 percent, and only 8 percent had

LTV ratios above 80 percent in September 2012. The LTV ratios for first-time home buyers in Italy are

at the lower range of those in euro area countries. The Bank of Italy estimates that the share of

mortgages in negative equity is near zero.

4

The reduction in new mortgages is partly due to a drop in mortgage substitution and subrogation, as interest rates

on new mortgages became less favorable.

5

The loan classification rules and supervisory practices are more conservative in Italy than elsewhere in Europe,

making comparison of NPL figures across countries potentially misleading.

6

The increase in past due loans is partly explained by the expiration of exceptions that allowed banks to wait to

classify loans as past due until they had been in arrears for 180 days. Now that the exceptions have expired, loans

that have been in arrears for 90 days are classified as past due.

ITALY

12 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

19. Default rates on mortgages are low, more so for younger vintages. Stricter selection

criteria and lower LTV ratios for mortgage loans have translated into a pronounced decline in

default rates on mortgage loans concluded during 2009–11, compared to those granted in the three

previous years.

20. A low share of mortgages and variable interest rates limit further the balance sheet

risk for banks. Outstanding mortgage lending amounted to EUR 365 billion at end-December 2012,

accounting for some 15 percent of total bank credit. Most mortgages––about 70 percent––have

variable rates typically linked to the three-month Euribor, though of these, 10 percent have a cap on

the interest rate. The reduction in Euribor rates following the 2008 financial crisis reduced the debt

burden of indebted households. However, as part of the tightened credit conditions, lenders have

increased the spread over Euribor on new mortgages, to about 3½ percentage points, against an

average of 1 percent in the pre-crisis years.

21. Mortgage substitution and subrogation are commonly used to enhance the financing

terms. A 2007 reform liberalized the mortgage market, including through the elimination of pre-

payment penalties, effectively increasing the mobility of mortgage customers. Mortgage

substitution, where a borrower renegotiates the contract (with the same bank or a new bank) to

obtain better financing conditions, possibly also amending the amount of the loan, or mortgage

subrogation, where borrower ends the contract and start a new contract (with the same or another

bank) to obtain better financing conditions, have been common in past years when interest rates

were low and falling. However, with worsening financing terms on new mortgages in 2011–12,

mortgage substitutions and subrogations are now less attractive. Mortgage substitutions and

subrogations amounted to about 12 percent of new mortgages in 2011, down from 20 percent

in 2009 and 16 percent in 2010, and are expected to have decreased further in 2012. Renegotiations

with the same banks were done for 7½ percent of mortgages in 2008, 3 percent in 2009 and

1–2 percent in 2010–11. The number of debt restructurings, where the bank incurs a loss, is very

limited (less than 0.1 percent of loans in December 2012).

22. Banks and the government have adopted measures to protect low-income and

distressed borrowers during the crisis. Under the initiative of the Italian Banking Association and

the main consumer organizations, a moratorium on mortgages was implemented in February 2010,

with wide participation from banks (Box 1). The moratorium expired in March 2013, and has enabled

50

60

70

80

90

100

50

60

70

80

90

100

Typical Loan-to-Value for a First-Time

Home Buyer

2007

2011

Source: Bank of Italy.

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

Yr disb.

+1 yr

+2 yrs

+3 yrs

+4 yrs

+5 yrs

+6 yrs

+7 yrs

+8 yrs

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

New Mortgage Loans in Default,

by Year of Disbursement

(in percent of number of contracts)

Source: Bank of Italy.

ITALY

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 13

around 100,000 homeowners to suspend repayments. Since banks do not incur a loss, mortgage

under the moratorium are not classified as “restructured” and are not considered part of impaired

loans. About 70 percent of those benefiting from the moratorium have resumed regular payments

at the end of the suspension, suggesting that the measure has improved the creditworthiness of the

participating households (see Bartiloro, Carpinelli, Finaldi Russo and Pastorelli, 2012, and Bank of

Italy, 2012c). The government’s Solidarity Fund (Box 1) is targeted at low-income households and

contributes to interest payments on mortgage loans for first-time home buyers during payment

suspensions. The capital endowment of EUR 20 million for 2011 was quickly exhausted, and

contributed to the interest payments of 5,000 households. A further EUR 20 million have been

allocated for 2012–2013.

23. Mortgage loans are full recourse under Italian law, offering considerable protection to

creditors. As in other countries in continental Europe, borrowers in Italy must repay their debt in

full, regardless of any change in the value of the property, and a creditor can in some cases attach

other (present and future) assets of the debtor.

24. The recent law on personal bankruptcy provides support for households that are

unable to pay their debt. Under the new law, over-indebted households can chose between two

new insolvency procedures; restructuring and liquidation. The restructuring is done with the

intervention of an ad-hoc body, and if feasible, approved by a judge. The debtor can propose an

agreement that can, among other, postpone payment deadlines or discount the total debt.

However, if the procedure encompasses secured debts, creditors should be repaid no less than the

collateral market value. The liquidation process is managed by an agent appointed by a judge, and

once started, prohibits new legal action against the debtor. If the liquidation of all the debtor’s

assets is closed but the debt is not yet fully paid off, the debtor can ask the court for a discharge,

which can be granted if strict conditions are satisfied.

7

25. The lengthy process to recover collateral affect banks’ expected recovery values. The

legal process to repossess collateral can be initiated after single or multiple delays in the payment of

installments. The average length of the legal procedures leading to repossession was about three

years in 2011, having improved from six years in 2001. The lender can, in addition, activate a

foreclosure procedure on other assets of the debtor, consistent with the full recourse legislation.

7

The debtor needs to prove good faith, i.e., the debtor needs to be cooperative, not having been sentenced for

bankruptcy crimes and not responsible for the default, and not having been granted a discharge of debt in the

previous eight years.

ITALY

14 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Figure 3. Italy: Households’ Financial Conditions

Credit growth has turned negative, and interest rates on

new loans remain high

Bank credit standards have tightened and demand for

credit has declined substantially.

The flow of new bad household loans is stable at a low

level

The stock of bad debt reflects a large amount of legacy

assets

The stocks of past due and substandard household loans

are on the rise

Loan-to-value ratios are low, but have come down, further

as has the use of mortgages for house purchases

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

1997

1999

2001

2003

2005

2007

2009

2011

2013

Ratio of New Bad Debt to Outstanding

Household Loans

(In percent, annualized)

Source: Bank of Italy.

50

60

70

80

50

60

70

80

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

Household Mortgage Financing

(In percent)

Loan-to-value ratio

House purchases with mortgage

Source: Bank of Italy.

-100

-80

-60

-40

-20

0

20

40

60

80

100

-100

-80

-60

-40

-20

0

20

40

60

80

100

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

Bank Lending Standards and Demand

(Net percentages) 1/

House purchase (credit standards)

House purchase (demand)

Consumer credit (credit standards)

Consumer credit (demand)

Source: Bank Lending Survey, Bank of Italy.

1/ Difference betweeen the sum of the percentages for tightened and eased for

credit standards and increased and decreased for loan demand.

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

1998

2000

2002

2004

2006

2008

2010

2012

Households' Bad Debt

In percent of outstanding loans

Source: Bank of Italy.

0

1

2

3

4

5

0

1

2

3

4

5

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

Impaired Household Loans, Excluding Bad Debts

In percent of total loans

Past due

Restructured

Substandard

Source: Bankof Italy.

June

2013

0

2

4

6

8

10

-5

0

5

10

15

20

Jan-07

Dec-07

Nov-08

Oct-09

Sep-10

Aug-11

Jul-12

12- Month Credit Growth and Interest Rates 1/

(In percent)

Credit growth (lhs)

Interest rate, consumer credit

Interest rate, mortgage

Source: Bank of Italy and ECB.

1/ Corrected for securitization. Interest rates on new loans (rhs).

ITALY

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 15

Box 1. Italy—Support Measures for Low-Income and Distressed Households

Moratorium. The moratorium promoted by the Italian Banking Association together with the

main consumer organizations, has allowed households in difficulty to suspend mortgage loan

repayments for at least 12 months, under the following conditions:

Mortgage not higher than EUR 150,000 for the purchase or restructuring of the primary

residence.

Annual household income up to EUR 40,000.

Loss of main income source after January 1, 2009, because of job loss, job reduction (including

under the Wage Supplementation Fund) for at least 30 days, or death of household main income

earner.

The suspension of payment include principal or principal and interest payments, and the

amortization period of the mortgage is extended for the period of the suspension, during which

interest continues to be due.

The participation of banks has been wide (92 percent). Since February 2010, the moratorium has

enabled around 85,000 homeowners (approximately 30 percent of mortgage holders in the lowest

income quartile) to suspend repayments, amounting on average to EUR 7,130 (approximately one

quarter of the disposable income of mortgage holders in the lowest income quartile). The

moratorium expired in March 2013.

Solidarity Fund. The government’s Solidarity Fund is targeted at low-income households and

contributes to interest payments on mortgage loans for first-time home buyers during payment

suspensions. The selection criteria are stricter than for the moratorium; in particular, those

benefiting from the Wage Supplementation Fund do not qualify, and bank participation is

mandatory. The Fund’s capital endowment of EUR 20 million for 2011 was quickly exhausted, and

contributed to the interest payments of 5,000 households. A further EUR 20 million has been

allocated for 2012–13.

In addition, the government has put in place a credit fund for parents of newborn children, valid

until 2014. Between 2010 and 2011, this fund disbursed loans totaling EUR 116 million to 21,000

households (0.2 percent of total loans to households). Finally, a guarantee funds for purchase of a

primary residence by young couples has been set up, where the government covers 50 percent of

the residual amount due in case of insolvency. The latter fund has been used scarcely, and the

conditions, in particular the cap on the spread applied to variable rate mortgages are currently

under review.

ITALY

16 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

D. Sensitivity Analysis

26. This section analyzes the risk to financial stability from household indebtedness. The

analysis uses the dataset from the Bank of Italy’s Survey of Household Income and Wealth (2010),

which allows a detailed analysis of households’ indebtedness across income groups. The 2010

Survey covers 7,951 households in Italy. To assess vulnerabilities, the analysis considers the financial

situation of households in 2010 (the baseline) and the impact of a set of hypothetical

macroeconomic shocks illustrating the key risks to the household sector; a further fall in income, an

increase in interest rates, and a continued decline in housing prices.

8

Baseline

27. The debt burden of Italian households is modest. In 2010, only 22 percent of households

had mortgage or consumer credit, see Table 1 and Figure 1.

9

Indebtedness is larger in the more

wealthy percentiles of the income distribution. The median debt-service to income ratio for

indebted households is 10 percent. Considering the ratio of debt payment to income as an indicator

of vulnerability, a household is defined to be vulnerable if debt service exceeds 30 percent of

income—a conservative threshold. The proportion of vulnerable household in the total sample is

2¼ percent, which is low in an international perspective, and the proportion of vulnerable

households among indebted households is 10 percent.

28. The lowest income group represents the most vulnerable group among indebted

households. Their median debt payment to income ratio was 18 percent, against 10 percent for all

indebted households. As a result, the share of distressed households was 29 percent for this income

group, about the double of that of the second lowest income group.

29. Vulnerable households hold a considerable share of total household debt. In total,

vulnerable households hold 27 percent of total household debt, though with large variation across

income groups. In the lowest income group, almost 75 percent of the debt is held by vulnerable

households, whereas the proportion is about 12 percent in the highest income group.

30. A large part of the debt of vulnerable households (debt at risk) is covered by real and

financial assets. The positive net wealth position, defined as real and financial assets minus financial

debt, provides a buffer for most indebted households. Only 1.2 percent of total debt is held by

vulnerable households (e.g., with debt service above 30 percent of income) that do not have a

positive net wealth position. The proportion is somewhat higher for the lowest income group; at

3 percent. In line with this, the loan default rate for Italian households is relatively low.

8

The survey is bi-annual and the 2012 dataset will become available in early 2014. See Bank of Italy (2011) for a

sensitivity analysis based on an extrapolation of the dataset to 2012.

9

The definition of debt used here includes mortgages and consumer credit, but excludes credit cards, overdrafts, and

business loans. If debt on credit cards and overdrafts are included, 27 percent of households are indebted. Income

includes non-monetary income.

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 17

Table 1. Italy: Household Debt Burden (2010)

All households

Indebted households

Income

Proportion

of indebted

households

(in percent

of total)

Proportion

of distressed

households

(in percent

of total)

Ratio of

debt

payment to

income

(median)

Share of

distressed

households

(in percent)

Share of

debt at risk

(in percent)

Debt at risk not

covered by

household assets

(in percent of

loans)

<20

11.3

3.3

18.2

29.1

73.2

3.0

20-40

16.7

2.5

12.6

15.1

40.9

1.0

40-60

22.2

2.6

11.5

11.9

42.4

1.5

60-80

27.2

1.7

10.2

6.3

21.6

0

80-90

28.3

0.6

9.4

2.2

12.0

4.3

90-100

32.8

0.6

6.9

1.9

12.5

0

Total

21.6

2.2

10.1

10.0

26.5

1.2

Source: Staff estimates using the Bank of Italy’s 2010 Household Income and Wealth Survey.

ITALY

ITALY

18 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Figure 4. Italian Household: Baseline Debt Vulnerability

The debt burden of Italian households is moderate and in

line with euro area averages

Indebtedness is higher for higher income groups, but

vulnerabilities are largest in the lower income groups

Debt service constitutes a larger share of income in the lower

income groups, making households more vulnerable

The debt of vulnerable households is mostly covered by

positive net wealth positions

Source: IMF staff estimates based on the Bank of Italy’s 2010 Household Income and Wealth Survey and ECB (2013) for

cross-country data on debt burden.

Sensitivity Test Scenarios

31. The sensitivity analysis considers the impact on the number of vulnerable households

and debt at risk of a set of hypothetical macroeconomic shocks. It takes the 2010 balance

sheets as the starting point and simulates the impact of the shocks to interest rates and income on

households, comparing the share of vulnerable households and households’ debt-servicing capacity

with the baseline figures. Since the results depend also on the valuation of net wealth, a house price

shock is also included.

0

5

10

15

20

25

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

Euro area

Germany

France

Italy

Spain

Debt Burden 1/

In percent of household income

Debt

Debt service (rhs)

1/ 2010, except for Spain (2008). For indebted households.

0

20

40

60

80

100

0

20

40

60

80

100

<20

20-40

40-60

60-80

80-90

90-100

All

Share of Indebted and Vulnerable Households,

by Income Group

(in percent of total households)

Indebted households

Vulnerable households

0

20

40

60

80

100

0

20

40

60

80

100

<20

20-40

40-60

60-80

80-90

90-100

All

Median Debt Service to Income and Share of

Vulnerable Households, by Income Group

(in percent of indected households)

Debt-service-to-income ratio

Vulnerable households

0

20

40

60

80

100

0

20

40

60

80

100

<20

20-40

40-60

60-80

80-90

90-100

All

Debt at Risk, by Income Group

(in percent of total debt)

Debt at risk

Debt at risk not covered by assets

ITALY

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 19

32. The sensitivity tests find that credit risk from households is mostly mitigated by their

positive net wealth position, even under severe shocks. Interest rate and income shocks have a

moderate impact on debt-at-risk, in particular when net wealth is taken into consideration. House

price shocks, however, due to the importance of real assets in financial assets, could have a

substantial impact on households’ net wealth and the collateral coverage of their loans.

33. Households are vulnerable to higher interest rate, though uncovered debt at risk

remains fairly moderate even under a severe scenario. About 60 percent of mortgages in the

survey have variable rates (against 70 percent nationally), and a rise in the interest rate could make it

more difficult for household to service their existing mortgages. Assuming a 100 basis points shock

to variable interest rate mortgages––similar to the increase in rates on new mortgages in 2011–12––

would increase the share of distressed households to 11 percent and debt at risk would increase to

29 percent. In a more extreme scenario, where interest rates on mortgages increase by 300 basis

points, the share of distressed households increases to 13 percent, bringing debt at risk to

35 percent. The shocks particularly affect the number of distressed households among the lower

income groups. However, the share of debt at risk, not covered by households’ assets, even in the

most severe scenario (a 300 basis points hike in interest rates) is limited to 1.2 percent of total

household loans.

34. Income shocks have further large impact on debt-servicing capacity, but are also

mitigated by the net wealth position. In a downside scenario where income declines by 3 percent

(similar to the decline in gross household disposable income in 2012), the share of vulnerable

households would increase to close to 11 percent, brining debt at risk to 29 percent. In a more

severe scenario––such as a 15 percent decline in income––14 percent of indebted households would

become distressed, and 36 percent of debt would be at risk. A combined interest rate and income

shock would increase further the share of distressed households, but the debt at risk not covered by

households’ net assets would be limited to about 1.6 percent of total household loans even in the

most severe combined scenario.

35. A housing price shock could, however, have a significant impact on the value of

vulnerable households’ collateral. The debt-servicing capacity is not directly affected by housing

prices. But if housing prices fall, the collateral of the debt held by vulnerable households would be

reduced. A moderate decline in housing prices of 5 percent would increase somewhat debt-at-risk

not covered by assets to 1.6 percent of total household loans, reflecting the prudent loan-to-value

ratios applied to mortgages. But in a more severe downside scenario where housing prices fall

by 20 percent, debt at risk not covered by such collateral could increase to 12 percent, considerably

increasing credit risk for banks.

ITALY

20 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Table 2. Italy: Sensitivity Analysis of Indebted Households

(In percent of indebted households)

Income

Ratio of

debt

payment

to income

(median)

Share of

distressed

households

(in percent)

Share of debt

at risk

(in percent)

Debt at risk not

covered by

household

assets

(in percent of

loans)

Baseline

10.1

10.0

26.5

1.2

Shocks

Interest rate increase

Moderate (100 bps)

12.2

10.7

29.3

1.2

Extreme (300 bps)

12.6

12.6

35.1

1.2

Income decline

Moderate (3 percent)

12,2

10.6

29.4

1.3

Extreme (15 percent)

13.9

14.3

35.5

1.6

House price decline

Moderate (5 percent)

10.1

10.0

26.5

1.6

Extreme (20 percent)

10.1

10.0

26.5

11.7

Combined shock

(Interest rate increase and

income decline)

Moderate (100 bps, 3

percent)

10.7

11.3

30.6

1.3

Extreme (300 bps, 15

percent)

12.6

17.2

43.5

1.6

Source: Staff calculations using the Bank of Italy’s 2010 Household Income and Wealth Survey.

ITALY

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 21

Figure 5. Italian Household: Sensitivity Analysis

Higher interest rates would increase the share of

vulnerable households, especially in mid-income groups

The impact on debt at risk (not covered by net assets) is

limited even in a severe scenario, given high wealth

An adverse income shock would also directly reduce debt-

servicing capacity

But again, large household wealth impact constitutes an

important collateral buffer

A combined severe interest rate and income shock would

make almost 50 percent of households distressed

But as before, large household buffers would dampen the

impact of debt at risk

0

10

20

30

40

50

0

10

20

30

40

50

<20

20-40

40-60

60-80

80-90

90-100

All

Combined Interest Rate and Income Shock:

Share of Vulnerable Households,

by Income Group

(in percent of indebted households)

Baseline

Moderate (Interest +100 bps, income -3%)

Extreme (Interest +300bps, income -15%)

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

<20

20-40

40-60

60-80

80-90

90-100

All

Combined Interest Rate and Income Shock:

Share of Uncovered Debt at Risk,

by Income Group

(in percent of total debt)

Baseline

Moderate (Interest +100bps, income -3%)

Extreme (Interest +300bps, income - 15%)

0

10

20

30

40

50

0

10

20

30

40

50

<20

20-40

40-60

60-80

80-90

90-100

All

Interest Rate Shock:

Share of Vulnerable Households,

by Income Group

(in percent of indebted households)

Baseline

Moderate (100 bps)

Extreme (300 bps)

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

<20

20-40

40-60

60-80

80-90

90-100

All

Interest Rate Shock:

Share of Uncovered Debt at Risk,

by Income Group

(in percent of total debt)

Baseline

Moderate (100 bps)

Extreme (300 bps)

0

10

20

30

40

50

0

10

20

30

40

50

<20

20-40

40-60

60-80

80-90

90-100

All

Income Shock:

Share of Vulnerable Households,

by Income Group

(in percent of indebted households)

Baseline

Moderate (3 percent)

Extreme (15 percent)

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

<20

20-40

40-60

60-80

80-90

90-100

All

Income Shock:

Share of Uncovered Debt at Risk,

by Income Group

(in percent of total debt)

Baseline

Moderate (3 percent)

Extreme (15 percent)

ITALY

22 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Figure 5. Italian Household: Sensitivity Analysis (concluded)

A house price shock does not directly affect households’

debt-servicing capacity on existing debt

But could severely reduce the value of collateral for

already vulnerable households

1/ Based on simulations of severe shocks to interest payments due ( 100 and 300 basis points increase), to income (3 and 15

percent decline), to a combination of interest payment and income, and to housing prices (5 and 20 percent).

THE ITALIAN NON-FINANCIAL SECTOR

10

A. Non-Financial Corporate Balance Sheets

36. The Italian corporate sector is dominated by SMEs. The SME’s share in business valued

added is above 70 percent, with 33 percent produced by micro enterprises, compared to EU

averages of 58 percent and 22 percent, respectively.

11

37. The debt burden of the corporate sector is moderate, but leverage is high. Corporate

balance sheets, made fragile by the prolonged recession, are weighed down by a historically high

level of debt in relation to both value added and equity. Leverage has increased during the crisis,

though mostly reflecting a decline in the value of equity. On average, Italian firms’ leverage is

among the highest in the euro area (Figure 6). SMEs are more highly leveraged than other firms.

In 2011, micro firms had a leverage ratio of 58 percent and small firms 55 percent, both above the

average of 52 percent in the Bank of Italy’s dataset of Italian companies. Large companies have

below average leverage (at 49 percent).

10

In this paper, the terms corporate sector, corporate and firms are used to refer to non-financial corporations.

11

European Commission (2011). A micro firm employs fewer than 10 persons and its annual turnover and/or balance

sheet total does not exceed EUR 2 billion. A small firm employs fewer than 50 persons and its annual turnover and/or

balance sheet total does not exceed EUR 10 million. A medium-sized firm employs fewer than 250 persons and its

annual turnover or balance sheet total does not exceed EUR 50 million or EUR 43 million, respectively.

0

10

20

30

40

50

0

10

20

30

40

50

<20

20-40

40-60

60-80

80-90

90-100

All

House Price Shock:

Share of Vulnerable Households,

by Income Group

(in percent of indebted households)

Baseline

5 pecent

20 percent

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

<20

20-40

40-60

60-80

80-90

90-100

All

House Price Shock:

Share of Uncovered Debt at Risk,

by Income Group

(in percent of total debt)

Baseline

5 pecent

20 percent

ITALY

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 23

38. The reliance on bank financing is high, in particular for SMEs. In 2011, bank lending to

firms represented 56 percent of GDP, against 49 percent on average for the euro area and

35 percent for Germany and 43 percent for France. About 50 percent of non-financial corporations’

financial debt is from banks, but for SMEs, the reliance on bank debt is higher, at 73 percent. Also,

Italian companies’ reliance on bond financing is limited. In 2012, the ratio of securities to loans was

8 percent, against 12 percent on average for the euro area and 40 percent for the United Kingdom.

The level and composition of Italian firms’ bank debt made them vulnerable to higher interest rates

and tighter bank lending standards during the crisis.

39. A large share of debt has short maturity. Loans with an original maturity of less than one

year make up 45 percent of firms’ bank debt in Italy, compared with 24 percent in the euro area. The

maturity of debt has shortened during the crisis, partly reflecting that bank lending standards

tightened more for long-term than short-term financing. SMEs are more vulnerable, with 54 percent

of their bank debt being short term.

40. Italian firms face headwinds from weak profitability. The protracted recession has

caused a sharp decline in profitability, with gross operating profit of firms continuing to fall in 2011,

having recovered in most large European economies, and its ratio to value added falling to the

lowest level since the 1990s (34 percent). The proportion of profit-making firms was 57 percent

in 2011, while 25 percent were loss-making (Figure 6). Exporting firms are faring somewhat better

than other firms, with 65 percent recording profits and 23 percent recording losses.

41. The construction and real estate sectors have been hit strongly by the crisis. The

recession in the construction sector started in 2005, earlier than the economy-wide recession,

following a prolonged expansion since the end of the 1990s. As the financial crisis deepened, the fall

in non-residential investment has been particularly severe, with non-residential investment currently

at 70 percent of its pre-crisis level, and residential investment at 85 percent. Despite the decline in

investment, the stock of unsold new houses suggests that there is a considerable over-supply in the

market.

42. Delays in intra-firm payments reinforce payment difficulties. The need of many firms for

external financing continued to reflect the large delays in payment of business transactions. The

average payment duration for Italian firms was 96 days in 2012, among the longest in the euro area

(Intrum Justitia, Figure 6). The payment delays have increased during the crisis, and the percentage

of firms with very late payments (more than 60 days beyond the agreed payment date) was

9 percent in 2013 Q1 (Cerved group). The delays in intra-firm payments to some extent are due to

the delays payments by the public administration—at an average of 180 days, the longest in the

euro area, which is currently being addressed (see section III.B).

43. Firms’ liquidity buffers have been relatively stable. The average liquidity ratio (current

assets to current liabilities) has been relatively stable at 114 percent during the crisis,

two percentage points below the average in the pre-crisis years (Cerved group). It increased

from 2009 to 2011 for small firms, whereas it decreased for medium and large enterprises. Firms can

still rely on substantial bank credit lines. The ratio between drawn and granted credit lines is equal

ITALY

24 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

to 57 percent, though it has been increasing in recent years (Central Credit Registry). The ratio is

lower for larger firms (with more than 20 employees), suggesting that these firms can rely on larger

liquidity buffers.

B. Financial Linkages

44. Bank credit to firms has declined substantially since the onset of the crisis. The growth

in bank loans to firms, net of repos and bad debts, began to slow from the middle of 2011 and

turned negative in mid-2012. By May 2013, credit was contracting at 3.6 on an annual basis. Unlike

the previous phase of reduction in credit in 2009, the contraction of the past months was greater for

small firms. The rising trend of bank interest rates for firms, under way since the middle of 2010,

slowed somewhat in 2012. In June, interest rates on new loans to firms were on average 3½ percent,

90 basis points above the euro area average reflecting continued financial fragmentation.

45. The decline in credit reflects both tighter credit conditions and slower demand.

12

The

Bank Lending Survey shows that both demand and supply factors have affected credit, though with

different intensity at varying stages of the crisis (Figure 7). The slowdown in credit to firms

during 2008–09 reflected to a large extent weak loan demand. From 2010 onward, when the

economy recovered, supply constraints started playing an increasingly important role, and by the

second half of 2011 at the peak of the Italian sovereign crisis, supply factors were prevailing.

However, as demand collapsed in 2012, the situation reversed, so that weak demand now tends to

be the stronger factor driving the decline in credit. Consistent with this, according to the Survey of

Industrial and Service Firms, some 40 percent of firms reported a worsening of access to credit in the

second half of 2011, twice as many as in the corresponding period of 2010. The leading reason cited

for the deterioration was the cost of credit, but the share of firms that had trouble getting the

desired amount of financing also rose significantly. The percentage of firms reporting that they got

less than the full amount of credit requested reached its highest level since the start of the crisis.

12

See Zoli (2013) for a discussion of the role of supply and demand in explaining recent credit developments.

ITALY

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 25

Figure 6. Italy: Corporate Leverage, Funding Sources, and Profitability

Italian firms have high leverage in an international

perspective

Leverage is higher for smaller firms

Reliance on bank loan financing is large in Italy

The share of loss-making firms has increased and that of

profit-making firms has fallen

Profitability has not recovered in line with other European

economies

Delays in government and intra-firm payments are among

the highest in the euro area

30

35

40

45

50

55

60

65

70

30

35

40

45

50

55

60

65

70

2000

2002

2004

2006

2008

2010

2012

Firm Leverage, 2000-2012

(Debt to the sum of debt plus equity, in percent)

Italy

France

Germany

Spain

Euro area

UK

Source: National statistics agencies and central banks.

40

45

50

55

60

65

40

45

50

55

60

65

Micro

Small

Medium

Large

Total

Leverage, by Firm Size (2011)

Source: Bank of Italy.

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

180

200

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

180

200

Italy

Spain

Euro area

France

United

Kingdom

Germany

Payment Duration for Government and Businesses

(Average, in days, 2012)

Government

Businesses

Source: Intrum Justitia.

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

Operating Results

(Percent of firms)

Profit-making firms

Loss-making firms

Source: Bank of Italy.

-20

-15

-10

-5

0

5

10

15

-20

-15

-10

-5

0

5

10

15

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

Firms' Gross Operating Profit

(Annual change, in percent)

Euro area

Germany

Spain

France

Italy

UK

Source: Eurostat.

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

Germany

Italy

Euro area

Spain

UK

France

Loans

Bonds

Equity

Non-Financial Corporations' Financing , 2002 and 2011

(In percent of GDP)

Source: Eurostat.

ITALY

26 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

46. Firms’ financial difficulties have translated into a sharp deterioration in banks’ asset

quality. The share of firms’ loans that are considered non-performing reached 25 percent in

June 2013, with that of smaller firms 26 percent. The flow of new bad debts (as a ratio of

outstanding firm loans) have increased to 3 percent from about 1 percent pre-crisis (annualized,

Figure 7). The stock of bad debt was 14.1 percent of total firm debt in June 2013, of which less than

40 percent is secured with real assets. Default rates, in terms of number of borrowers defaulting

each year, have doubled relative to the pre-crisis years to 3 percent in 2012. For the more forward-

looking categories, in June 2013, substandard loans represented another 7.3 percent of total loans,

while restructured and past due were 1.1 and 2.6 percent, respectively. Once classified as non-

performing, the loan quality in most cases deteriorates, as shown by the transition dynamics

between the NPL categories, suggesting continued increases in bad loans going forward.

47. Loans to construction firms represent considerable risk for Italian banks. These loans

amounted to EUR 150 billion in 2011 or 10 percent of total credit to the private sector. Based on

Cerved Group data, 52 percent of construction firms made losses in 2011, compared to 35 percent

for manufacturing firms and 42 for the entire sample. In August 2012, 16 percent of bank loans to

construction firms were classified as bad debts and another 14 percent were impaired. Banks also

have a substantial exposure (EUR 120 billion) to real-estate service companies (sales, rentals,

management and brokerage). The quality of credit to these companies is deteriorating rapidly;

8 percent of all loans were classified as bad debts and another 14 percent were substandard,

restructured or past due.

48. The use of collateral to back loans has increased. The share of firms’ loans that are

backed by collateral or guarantees increased from 64 to 68 percent between 2007 and 2012. The

increase was stronger for smaller firms, whose access to new financing is more conditioned on the

availability of collateral. Many firms benefit from guarantees issued by the entrepreneur (or a

member of the entrepreneur’s family), backed by personal real and financial assets. These kinds of

guarantees are estimated to represent about 15 percent of total real and financial assets used as

collateral or guarantees for loans. There is however no harmonized data reporting on collateral held

by banks and also no available data on unpledged assets that could be used as collateral or

guarantees for new loans.

-10

-8

-6

-4

-2

0

2

4

-10

-8

-6

-4

-2

0

2

4

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

Transition Between Impaired Loan Categories

In percent of total loans to firms

Worsen

Improve

Net improvement

Source: Bank of Italy.

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

Jan-06

Jan-07

Jan-08

Jan-09

Jan-10

Jan-11

Jan-12

Jan-13

Firms Non-Performing Loans

In percent of total loans to firms

Small firms

Large and medium-sized firms

Source: Bank of Italy.

ITALY

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 27

Box 2. Italy—Measures to Support SME Financing

During the crisis, several initiatives have been implemented to alleviate SMEs’ temporary

debt payment difficulties and support their access to credit:

Debt Payment Moratoria for SMEs. The government, the banking association, and business

associations signed an agreement in August 2009 to allow the suspension of principal

repayments on part of SME debt. During the first two years, the moratorium was applied to

debt totaling EUR 65 billion on 225,000 loans, resulting in the suspension of some

EUR 15 billion in loan repayments. A new moratorium with stricter eligibility criteria was agreed

in February 2012, which was applied to debt of EUR 28 billion as of April 2013. Although it

expired in June 2013, a new round of debt moratoria similar to previous ones was signed in

July 2013. The moratoria have helped firms face temporary payment difficulties. According to

the Bank of Italy, regular payments are resumed for about 60 percent of loans after suspension,

suggesting limited forbearance risk.

Payment of Government Overdue Debt. To ease the liquidity problems of suppliers due to

late payments by government entities, the government approved in April 2013 a plan to pay a

substantial part (EUR 40 billion, 2½ percent of GDP) of its overdue debt during 2013–14. The

implementation of the plan, which was approved by Parliament in May 2013, should bolster

firms’ liquidity position and improve their debt-servicing capacity, and more generally, boost

growth, thereby enhancing firm profitability. Moreover, in August 2013 a plan to further

increase the payment by EUR 7 billion in 2013 was approved.

Guarantee Fund for SMEs. The government’s Guarantee Fund for SMEs was boosted in

response to the crisis, by increasing its endowment, widening the eligibility criteria for firms,

easing the minimum requirement for the firm’s financial indicators, and providing a

government back-stop guarantee to allow a more favorable prudential treatment of the

guarantees. The value of the guarantee amounts to a maximum of 80 percent of the loan (or

EUR 1.5 million). Up to end-2012, the fund had given guarantees amounting to EUR 21 billion,

for total loan amounts of EUR 39 billion.

The SME Plafonds from Cassa Depositi e Prestiti (CDP). Since 2009, CDP has used its retail

deposit base to grant medium-and long-term credit to SMEs through banks at below-market

interest rates. The total amounts that can be provided are EUR 18 billion, 75 percent of the

banking system participates, and 60,000 firms have received financing so far.

Initiatives are also in place to strengthen capital and promote alternative financing

opportunities for SMEs, to reduce their leverage and reliance on bank funding. First, the

Italian Investment Fund (a EUR 1.2 billion private equity fund promoted by the government and

mainly funded by the largest Italian banking groups) supports capital strengthening and mergers

and acquisitions among medium and large enterprises. Second, to strengthen the capitalization of

firms and foster “internal” growth, the government has made the notional return on new equity

deductible from taxable income, according to the allowance for corporate equity principle. Finally,

the government increased fiscal incentives to facilitate the issuance of unlisted firms of

commercial paper and bonds.

ITALY

28 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Figure 7. Italy: Firms’ Financial Conditions

Credit to firms has declined, and interest rates remain high

despite lower euro area rates

Bank credit standards have tightened substantially, and

demand for credit has declined.

The flow of new bad debts from firms is on an increasing

trend

Firms’ non-performing loans have doubled in the past five

years

New bankruptcy proceedings reached new highs in 2012,

making it more challenging to reduce the length

The use of corporate restructuring options is moderate and

below pre-crisis levels

0

2

4

6

8

10

-5

0

5

10

15

20

Jan-07

Dec-07

Nov-08

Oct-09

Sep-10

Aug-11

Jul-12

12- Month Credit Growth and Interest Rates 1/

(In percent )

Credit growth (lhs)

Interest rates, loan < €1 million

Interest rates, loan > €1 million

Source: Bank of Italy and ECB.

1/ Corrected for securitization. Interest rates on new loans (rhs).