FUTURE TRENDS IN HOUSING TENURE AND THE

ADEQUACY OF RETIREMENT INCOME

RACHEL SLAYMAKER, BARRA ROANTREE, ANNE NOLAN AND

CONOR O'TOOLE

RESEARCH

SERIES

NUMBER 143

JULY 2022

E

V

I

D

E

N

C

E

F

O

R

P

O

L

I

C

Y

FUTURE TRENDS IN HOUSING TENURE AND THE

ADEQUACY OF RETIREMENT INCOME

Rachel Slaymaker

Barra Roantree

Anne Nolan

Conor O’Toole

JULY 2022

RESEARCH SERIES

NUMBER 143

Available to download from www.esri.ie

The Economic and Social Research Institute

Whitaker Square, Sir John Rogerson’s Quay, Dublin 2

https://doi.org/10.26504/rs143

This Open Access work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and

reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited.

ABOUT THE ESRI

The mission of the Economic and Social Research Institute is to advance evidence-

based policymaking that supports economic sustainability and social progress in

Ireland. ESRI researchers apply the highest standards of academic excellence to

challenges facing policymakers, focusing on 12 areas of critical importance to 21st

Century Ireland.

The Institute was founded in 1960 by a group of senior civil servants led by

Dr T.K. Whitaker, who identified the need for independent and in-depth research

analysis to provide a robust evidence base for policymaking in Ireland.

Since then, the Institute has remained committed to independent research and its

work is free of any expressed ideology or political position. The Institute publishes

all research reaching the appropriate academic standard, irrespective of its

findings or who funds the research.

The quality of its research output is guaranteed by a rigorous peer review process.

ESRI researchers are experts in their fields and are committed to producing work

that meets the highest academic standards and practices.

The work of the Institute is disseminated widely in books, journal articles and

reports. ESRI publications are available to download, free of charge, from its

website. Additionally, ESRI staff communicate research findings at regular

conferences and seminars.

The ESRI is a company limited by guarantee, answerable to its members and

governed by a Council, comprising 14 members who represent a cross-section of

ESRI members from academia, civil services, state agencies, businesses and civil

society. The Institute receives an annual grant-in-aid from the Department of

Public Expenditure and Reform to support the scientific and public interest

elements of the Institute’s activities; the grant accounted for an average of 30 per

cent of the Institute’s income over the lifetime of the last Research Strategy. The

remaining funding comes from research programmes supported by government

departments and agencies, public bodies and competitive research programmes.

Further information is available at www.esri.ie

THE AUTHORS

Rachel Slaymaker and Barra Roantree are Research Officers at the Economic and

Social Research Institute (ESRI). Anne Nolan and Conor O’Toole are Associate

Research Professors at the ESRI. All hold adjunct positions at Trinity College Dublin

(TCD).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The research was funded by the Pensions Council under a Research Programme on

‘Housing and Pensions’. The authors thank the Central Statistics Office (CSO) for

access to Survey on Income and Living Conditions (SILC) microdata, and the Irish

Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA) for access to the TILDA microdata. Thanks

also to the members of the Pensions Council, and to the members of the Research

Programme Steering Committee (Ciaran Diamond, Des Henry, Brendan Kennedy,

Munro O’Dwyer) for helpful comments and guidance throughout the period of this

research programme. We are grateful to participants at an ESRI lunchtime seminar,

and to the external and internal reviewers for helpful comments. All views, errors

and omissions remain the sole responsibility of the authors.

This report has been accepted for publication by the Institute, which does not itself take institutional

policy positions. All ESRI Research Series reports are peer reviewed prior to publication. The authors

are solely responsible for the content and the views expressed.

Table of contents | v

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................................................................................. VII

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................................... IX

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................ 1

1.1 Context ................................................................................................................ 1

1.2 Existing evidence ................................................................................................. 3

1.3 Contribution and report structure....................................................................... 7

CHAPTER 2 POLICY CONTEXT .............................................................................................................. 9

2.1 The Irish pension system ..................................................................................... 9

2.2 The Irish housing market ................................................................................... 11

CHAPTER 3 HOUSING TENURE AND COST SCENARIOS ..................................................................... 15

3.1 Housing tenure .................................................................................................. 15

3.2 Current housing costs ........................................................................................ 18

3.3 Homeownership simulation scenarios .............................................................. 20

3.4 Summary ............................................................................................................ 31

CHAPTER 4 INCOME ADEQUACY IN RETIREMENT ............................................................................ 33

4.1 Introduction ....................................................................................................... 33

4.2 Data and methodology ...................................................................................... 33

4.3 Results and empirical findings ........................................................................... 35

4.4 Summary ............................................................................................................ 40

CHAPTER 5 CONCLUSIONS ................................................................................................................ 43

5.1 Summary of main findings ................................................................................. 43

5.2 Policy implications ............................................................................................. 45

REFERENCES ........................................................................................................................................ 49

APPENDIX I SUPPLEMENTARY RESEARCH FOR CHAPTER 3.................................................................

53

APPENDIX II SUPPLEMENTARY RESEARCH FOR CHAPTER 4 ............................................................... 55

vi | Future trends in housing tenure and the adequacy of retirement income

LIST OF TABLES

Table 3.1 What % of non-transitioners are constrained by different factors? ................................ 24

Table 3.2 Homeownership rate simulations by age cohort (%) – additional scenarios ................... 26

Table 3.3 Homeownership rate simulations for 25-34 cohort (%) .................................................. 28

Table 4.1 Poverty line (AROP) measures of income adequacy ........................................................ 36

Table 4.2 Poverty gap for various measures of income adequacy .................................................. 38

Table 4.3 Logistic regression of the factors associated with AROP status, baseline simulations,

broader income measure ................................................................................................. 40

Table A.1 Evidence of likelihood of receiving gift / amount by recipient characteristics ................ 53

Table A.2 25th percentile house price by NUTS 3 region – 2019 ..................................................... 53

Table A.3 Logistic regression of the factors associated with AROP, baseline simulations, narrow

income measure ............................................................................................................... 55

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1.1 Homeownership rates by decade of birth cohort .............................................................. 2

Figure 2.1 Trends in housing costs (year-on-year change, %) ........................................................... 12

Figure 2.2 Tenure shares Ireland ....................................................................................................... 13

Figure 2.3 Housing supply changes – ESB connections – overall and per 1,000 persons

aged 20-50 ........................................................................................................................ 14

Figure 3.1 % Homeowners by age cohort 1987-2015 ....................................................................... 16

Figure 3.2 % Households in housing tenures by age cohort 2018-2019 ........................................... 17

Figure 3.3 Mean housing cost-to-income ratio (HCTI) % by tenure and age cohort ........................ 18

Figure 3.4 % Households with high housing costs (HCTI>30%) by age cohort .................................. 19

Figure 3.5 Overview of static tenure assignment method ................................................................ 21

Figure 3.6 % Homeowners after static tenure transition, by age cohort .......................................... 23

Figure 3.7 % Homeowners 25-34 cohort – different house price and income growth scenarios .... 29

Figure A.1 Distribution of after housing costs income, by scenario (broad definition) .................... 56

Figure A.2 Distribution of after housing costs income, by scenario (narrow definition) .................. 56

Abbreviations | vii

ABBREVIATIONS

AHC After housing cost

AROP At risk of poverty

AT-HOME Affordability and Tenure Housing Microsimulation Engine

BHC Before housing cost

CSO Central Statistics Office

HAP Housing Assistance Payment

PRSI Pay Related Social Insurance

RAS Rental Assistance Scheme

RS Rent Supplement

SILC Survey on Income and Living Conditions

SPA State Pension Age

TILDA The Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing

TRIAM TILDA Retirement Income Adequacy Model

Executive summary | ix

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

CONTEXT AND RESEARCH RATIONALE

In recent years, Ireland has experienced a notable decline in homeownership and

a rise in the proportion of households in private rental accommodation.

Concurrently, the cost of both rents and house prices have risen markedly and

affordability challenges in terms of meeting housing costs have been well

documented. While these challenges are immediate in terms of the housing costs

burden, a longer-term issue arises as to how renting households will manage the

financial adjustment to retirement with ongoing rent payments. This transition

historically in Ireland has been smoothed by high homeownership rates and

mortgage amortisation which lowered the cost of housing payments and increased

financial assets. Indeed, existing international evidence suggests that being a

homeowner can provide a ‘double dividend’ of lowering housing costs and

increasing assets in retirement. This can help manage changes to income in

retirement and allow households to maintain their standard of living.

The continued requirement to cover housing costs for renters in retirement can be

seen as an additional vulnerability in terms of retirement income adequacy in

Ireland, over and above the general concern of sufficient pension income. While

considerable research to date has documented this well-known challenge of

providing a sufficient standard of living in retirement for many households in

Ireland, the drop in the homeownership rate layers an additional complication in

terms of the policy challenge.

To address these related issues, this report explores indicative future paths for

homeownership rates in Ireland and explores the impact in terms of income

poverty in retirement. Using data from the Survey on Income and Living Conditions

(SILC) and the Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA), we consider a number of

scenarios to assess the possibility of renting households becoming homeowners,

and then test the impact on income poverty rates if households were to continue

to have rental costs into retirement.

SUMMARY OF MAIN FINDINGS

A number of key findings emerge from this research:

Findings on homeownership rates

• Ireland has experienced a marked drop in homeownership rates in recent

years. This has been particularly acute for younger-aged households, with the

share of 25-34s who owned their own home halving between 2004 and 2015,

falling from 60 per cent to just 30 per cent. This has continued to fall for

x | Future trends in housing tenure and the adequacy of retirement income

households aged 25-34 and 35-44 since 2015. For these age groups, the

predominant tenure for non-homeowners is private rental with no policy

support (such as HAP, RAS etc).

• At present the share of households with high housing costs

1

clearly falls with

age. Over 1-in-5 households aged 25-34 face high housing costs, compared to

around 1-in-17 aged 55-64 and only 1-in-100 of those currently aged 65+. For

all age cohorts the incidence of high housing costs is notably higher for non-

homeowners.

• We undertake a range of simulations that vary income, credit, savings and

house prices to explore the possible transition of current renters to

homeownership. The results indicate a likely, and considerable, drop in the

achievable rate of homeownership relative to previous generations (and

current retirees) across all age groups;

o Homeownership rates are around 10 percentage points lower

(approximately 80 per cent) for those currently aged 55-64 and 45-54

compared with current retirees (approximately 90 per cent); this

differential is unlikely to close substantially for these groups given their

position in the lifecycle;

o The homeownership rate for those aged 35-44 is currently 58 per cent.

Our scenarios indicate that this age cohort could, at a maximum, reach

a homeownership rate of 71 per cent through home purchases in the

open market;

o There is likely greater uncertainty over the 25-34 age group given their

age and lifecycle earnings prospects. However, while alternative

scenarios (e.g. down-payment supports) would boost this cohorts’

homeownership rates, they remain significantly below those of

previous cohorts, and this is unlikely to change considerably unless their

income growth outpaces house price growth for a sustained period;

o As a result, the simulated rate of homeownership is lower again for the

youngest aged group, 25-34, with approximately one-in-two

households becoming homeowners in the majority of scenarios

explored.

• Multiple factors are likely causing the drop in homeownership rates including

labour market dynamics, the relative growth of house prices and incomes,

supply bottlenecks and credit availability. Using a static model, we do not

formally test for the drivers of homeownership in this report, nor do we take

1

High housing costs is defined as a housing cost-to-income ratio greater than 30 per cent.

Executive summary | xi

account of possible demographic changes (e.g. migration) that would change

the demand for housing.

Findings on income adequacy of future cohorts

• We explore the likely impact of lower rates of homeownership on measures

of income poverty for Irish individuals approaching retirement. Using data on

the group who are due to retire over the next five years (92 per cent of whom

own their home), we estimate that income poverty

2

in retirement rises from

9 per cent on a before housing costs basis to 14 per cent on an after housing

costs basis.

• Lower rates of homeownership are likely to lead to substantially higher after

housing costs income poverty rates. To demonstrate the impact of changes in

homeownership on income adequacy, and linking to our research above on

lower homeownership for younger households, we simulate income poverty

rates for those approaching retirement would reach 31 per cent under a low

homeownership scenario of 63 per cent, 28 per cent under a medium

homeownership scenario of 70 per cent, and 21 per cent under a high

homeownership scenario of 78 per cent, compared to 14 per cent under the

baseline homeownership rate of 92 per cent.

• Our analysis suggests that women, those with lower levels of education and

those living alone during working life are particularly vulnerable to income

poverty in retirement after housing costs are taken into account.

POLICY CONSIDERATIONS

A number of considerations for policy arise from our research:

• Ireland’s pension system (both public and private) has to date leveraged the

‘double dividend’ associated with homeownership – lower housing costs and

higher assets in retirement. It is unlikely that homeownership rates will be as

high in future and therefore consideration will have to be given to the most

appropriate policy response. This could include policies aimed at addressing

the housing costs element, the income adequacy element, or both.

• Policies could be targeted to improve incomes of older households or to

incentivise renting households to build up more resources earlier in their

lifecycle while in employment.

• Income-based support for older households could come in the form of

targeted supports to those groups of households most at risk of income

poverty. This would be more efficient in deadweight terms than blanket

measures to raise state pension rates which would also be fiscally expensive.

2

This is based on the official at risk of poverty threshold and a ‘broad’ definition of income. The ‘broad’ definition of

income includes income from state and supplementary pensions, as well as the annuitised value of net financial assets

(i.e. savings, stocks/shares, investment property, etc., minus any outstanding non-mortgage debt).

xii | Future trends in housing tenure and the adequacy of retirement income

Indeed, the latter approach may not be fiscally sustainable in the context of

the broader demographic pressures.

• The second area of intervention that shifts the housing costs risk in retirement

is to directly intervene for households with housing costs challenges. The

availability of a targeted instrument such as an income supplement or rent

subsidy to directly cover housing costs for those households who are proven

to be in housing costs distress could feature as part of the future policy

architecture.

• However, the availability of, and even the signalling of, such instruments could

alter the incentives for households to sufficiently accumulate resources earlier

in their working lives. Furthermore, such extensive subsidy supports for those

living in private sector accommodation risks adding to rental inflation and the

costs are likely to be prohibitively expensive for the State given the scale of

the projected fall in homeownership for future retirement cohorts.

• More generally in terms of broader housing policy, interventions at earlier

stages of the lifecycle are critical to help lower the housing costs future

cohorts will face in retirement. Instruments targeting increased supply which

impact the share of homeowners, increased direct provision of social housing

or which develop alternative, non-market renting cohorts such as cost rental

and expanded social housing can all help to lower the cost of housing at

retirement.

• It is however worth noting that while the scenarios in this report attempt to

provide an indicative range for future homeownership rates and the impact

on households’ income adequacy, any assessment that extrapolates across

such a long horizon is subject to considerable uncertainty. In particular, the

current 25-34 age cohort may be expected to experience further career

progression and income growth, which leads to considerable uncertainty in

projecting their likely homeownership rates in retirement.

• In addition, there is also uncertainty about the extent to which current (and

future) housing policy initiatives may increase the share of future

homeowners and/or ensure lower and more stable housing costs for future

cohorts of retirees. Therefore, there is certainly time for policies to influence

the outcomes of this research from both a housing tenure and income support

perspective.

• However, given future demographic projections and associated sustainability

challenges, it is unlikely the State will also be able to fully carry the cost burden

for the challenge of higher housing costs in retirement. Therefore, developing

a policy strategy which mixes lifetime incentives to accumulate retirement

assets during employment with an adequate safety net is most likely to be

required.

Introduction | 1

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

1.1 CONTEXT

A key area of policy concern is the extent to which those who are retired will have

adequate resources to fund their consumption in retirement (European

Commission, 2021; Government of Ireland, 2018; Mulligan et al., 2019). Assessing

the adequacy of incomes in retirement is not a straightforward task, particularly

for those who have not yet retired. A number of assumptions are required to

simulate the level of retirement income, while there are multiple definitions of

what one may want to consider as retirement income. In this report, we consider

adequacy with reference to some fixed level of income deemed sufficient to buy

essential goods and services: the so-called ‘poverty-line’ approach.

3

Much of the existing work in this area in the Irish context has focused on the extent

to which those who are either already retired or very close to retirement are at risk

of inadequate incomes in retirement (Beirne et al., 2020; Bercholz et al., 2019;

Nivakoski, 2014; Nivakoski and Barrett, 2019). While assessments of retirement

income adequacy are sensitive to the measure of adequacy adopted, and the

definition of retirement income, the most recent Irish estimates suggest that

approximately 9 per cent of those approaching the state pension age (SPA) over

the period 2022-2027 would be at risk of poverty using the 60 per cent of median

household disposable income poverty threshold, based on a definition of

retirement income that includes state and supplementary pension income, as well

as non-primary residence asset income (Beirne et al., 2020).

However, demographic, social and economic changes over recent decades mean

that future cohorts of retirees are likely to look very different to the current cohort

of retirees. One of the most important of these dimensions is housing tenure and

costs. According to the 2016 Census of Population, over 85 per cent of those aged

65+ owned their own home, the vast majority outright (Central Statistics Office,

2017). In addition, most of those aged 65+ renting do so from a local authority or

voluntary body, and thus may expect to have low and relatively stable housing

costs in retirement (Doolan et al., 2022). However, the age at which two-thirds of

the cohort own their own home (with or without a mortgage) has been increasing

steadily over time, from 28 years of age in 1991 to 41 in 2016 (Central Statistics

Office, 2017). This implies substantial differences in the projected tenure and

housing costs of younger cohorts.

3

See (Beirne et al., 2020) and (Crawford and O’Dea, 2012) for more detailed discussions of the conceptual and

measurement issues involved in assessing retirement income adequacy.

2 | Future trends in housing tenure and the adequacy of retirement income

These cohort-level changes in housing tenure can be illustrated in greater detail in

Figure 1.1. While more than 60 per cent of those born in the 1960s lived in a home

they or their partner owned by age 30, this proportion had fallen to 39 per cent for

those born in the 1970s and 32 per cent for those born in the early 1980s. While

there may be some catch-up at later ages (in part due to changing patterns of

family formation), the figure shows that rates of homeownership for previous

cohorts tend to level off after age 45 (Roantree et al., 2021).

FIGURE 1.1 HOMEOWNERSHIP RATES BY DECADE OF BIRTH COHORT

Source: Reproduced from Roantree et al. (2021) using the Survey of Income Distribution, Poverty and Usage of State Services; the Living

in Ireland survey; and the Survey on Income and Living Conditions.

Notes: Homeownership defined as being the head – or the partner of the head – of a household that lives in an owner-occupied dwelling

(i.e. adult children of owner-occupiers not counted as owning their own home).

The drop in homeownership documented above is likely caused by a range of

factors. As discussed in McQuinn et al. (2021), the tightening of credit access rules

following the onset of the financial crisis, coupled with historically low housing

supply and rising demographic demand, have led to rapidly rising house prices and

rents in Ireland. These factors have led to an increasingly evident housing

affordability challenge, in particular for young, urban renting households who have

faced rapidly increasing rental prices (Corrigan et al., 2019). While these problems

are currently acute, the longer-term implications for these households of how to

cover housing costs in retirement (in lower expected homeownership contexts) has

received less attention in the policy or research literature.

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

20 25 30 35 40 45 50 55

% who own their own home

Age

1940s 1950s 1960s 1970s 1980s 1990s

Introduction | 3

1.2 EXISTING EVIDENCE

1.2.1 Retirement income adequacy

Most assessments of retirement income adequacy in an Irish context have tended

to focus on those already retired, or close to retirement. For example, using data

from the Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA), Nivakoski (2014) and Nivakoski

and Barrett (2019) found that income replacement rates

4

were highest for women

and those at the bottom of the earnings distribution, more reflecting the lower

earnings of these groups immediately prior to retirement than high levels of

resources available in retirement. As replacement rates are sensitive to how

income (both pre- and post-retirement) is defined, and generally do not take into

account the wider resources of the household (e.g. from other family members

and/or from assets), or future risks to longevity, investments and healthcare needs

(Knoff et al., 2016), alternative benchmarks are required. An alternative approach

assesses the adequacy of retirement income by determining whether it is sufficient

to meet basic needs (i.e. having enough income to be able to purchase necessities

such as housing, food and clothing). This is assessed in terms of whether retirement

resources are below some benchmark of income poverty, typically the at-risk-of-

poverty threshold.

In this context, a recent study attempted to move beyond a single replacement

rate to consider multiple indicators of retirement income adequacy, varying not

only the definition of income, but also the benchmarks used to assess adequacy.

Beirne et al. (2020) used data from TILDA on the cohort of people born between

1955 and 1960 (and therefore expected to reach the state pension age over the

period 2022-2027) to assess the adequacy of their projected income in retirement,

using a variety of different benchmarks and definitions of retirement income.

5

The

analysis found that assessments of income adequacy in retirement were very

sensitive to the benchmark used. Even small changes in the benchmark resulted in

large changes in the proportion assessed as having inadequate resources in

retirement. For example, moving from a poverty-line benchmark of 60 per cent of

median household disposable income (the current at-risk-of-poverty threshold) to

a 50 per cent of median household disposable income benchmark (the OECD at-

risk-of-poverty threshold) resulted in a sharp fall in those with inadequate levels of

income in retirement (from 9.2 per cent to 3.0 per cent using a broad definition of

income that includes non-primary residence asset income in addition to state and

4

The retirement income replacement rate is defined as the ratio of post-retirement income (from pensions, annuitised

wealth holdings, etc.) to pre-retirement income. The current Pensions Roadmap 2018-2023 aims to ensure that the

state pension, in combination with supplementary pensions, replaces a sufficient proportion (between 50 and 60 per

cent) of an individual’s pre-retirement earnings so as to enable them to maintain a reasonable standard of living after

retirement (Government of Ireland, 2018).

5

In this report, we use this model, the TILDA Retirement Income Adequacy Model (TRIAM) developed in Beirne et al.

(2020), to assess the retirement income adequacy of current and future cohorts of retirees on an after housing costs

basis.

4 | Future trends in housing tenure and the adequacy of retirement income

supplementary pension income). In addition, across all benchmarks, broadening

the definition of income in retirement to include financial assets, and further still

to include half the value of owner-occupied housing wealth, substantially reduced

the proportions of those who were considered at risk of having inadequate

resources in retirement. While the issue of whether individuals should draw on

wealth in the form of primary residences to support living standards in retirement

is contentious, less so is that individuals should draw on other forms of wealth.

These results suggested that private non-pension, non-primary residence assets

play an important role in individuals’ preparedness for retirement.

1.2.2 Housing costs and retirement income adequacy

While the general literature on retirement income adequacy is considerable, few

assessments of retirement income adequacy consider explicitly the role of housing.

Housing can refer to a service (the accommodation that housing provides) and a

capital asset (the dwelling that produces the service) (Fahey and Norris, 2010). One

strand of the literature considers housing from the latter perspective, i.e. as an

asset that can be considered as a source of income in retirement. Fahey (2003)

notes that housing is a valuable asset in retirement which, in principle at least, can

be drawn upon to provide cash income later in life should the need arise (e.g. by

downsizing, equity release, or through family arrangements whereby younger

family members provide support to older family members in return for an explicit

or implicit promise of an eventual bequest). Banks et al. (2005), Crawford and

O’Dea (2012) and Beirne et al. (2020) all considered the role of owner-occupied

housing wealth in their assessments of retirement income adequacy in England

and Ireland, by examining the extent to which these assessments were affected by

the inclusion of half the annuitised value of owner-occupied housing wealth in the

definition of retirement income.

Dewilde and Raeymaeckers (2008) used data from the 2001 European Community

Household Panel (ECHP) to test the idea that housing policies can reduce poverty

in later life by promoting outright ownership, which in turn provides a ‘hidden’

source of income (also addressed using earlier data by Fahey et al., 2004a). Across

the ten Member States included in the ECHP (including Ireland), they found that

neither generous pensions nor high ownership rates had the strongest poverty-

reducing potential; lower poverty rates in older age were most strongly associated

with the provision of social housing for older people. Furthermore, they identified

a group of older people who were faced with a double disadvantage, in the sense

that in high homeownership countries, those who did not possess their own homes

also tended to receive low pension benefits.

In a comparative analysis of a selection of countries with differing housing and

pension systems in the early 2000s, Delfani et al. (2014) found little support for the

hypothesis that housing and pensions in older age were to some extent

Introduction | 5

interchangeable; the exception was in countries such as Ireland with high rates of

homeownership, and no mandatory earnings-related pension scheme. A detailed

analysis of the homeownership-pension trade-off in four European countries

(Belgium, Germany, Ireland and the Netherlands) using Survey on Income and

Living Condition (SILC) data for 2009 showed that outright homeownership among

the income-poor older population played a significant role in reducing poverty

(both income poverty and deprivation)

6

in old age (Delfani et al., 2015). In Ireland,

outright homeownership had a particularly strong effect on reducing deprivation

in older age.

Focusing on housing costs, a recent paper used data from the German Socio-

Economic Panel (GSOEP) to examine how rising housing costs over the period

1996-2017 have affected income poverty among the older population (aged 65+)

(Lozano Alcántara and Vogel, 2021). The German case is of particular interest as it

has one of the highest percentages of tenants (48.9 per cent in 2019) in Europe.

They found that the share of tenants aged 65+ at income poverty risk after housing

costs rose from 23.9 per cent in 1996 to 33.9 per cent in 2017, while for

homeowners the share remained broadly stable (and much lower) throughout the

period (at approximately 6-8 per cent). A Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition showed

that changes in housing costs between 1996 and 2017 explained most of the

increase in the old-age income poverty rate over the period.

Using data from Australia for 2017-2018, Bradbury and Saunders (2021) compared

before and after housing costs poverty rates across different population groups.

They hypothesised that the before housing costs measure would over-estimate

poverty among older people who often have low (mainly pension) incomes but also

face low housing costs because many of them own their homes outright. In

contrast, they found that the after housing costs poverty rate for single older

people was substantially higher than the before housing costs rate (23.4 per cent

vs. 15.9 per cent), and largely the same on a before and after housing costs basis

for older couples (at approximately 9 per cent). Examining trends over time since

2007, they found that the sharp increase in house prices that has left many

Australians with unpaid mortgages when they reach pension age, and the growing

number of both young and old Australians who are unable to gain access to

homeownership and forced to rely on the private rental market, explained these

patterns.

In the Irish context, Fahey (2003) calculated before and after housing costs at risk

of poverty rates by age cohort using data from 1998. He found that while the after

housing costs poverty rate among older households was 10 percentage points

6

I.e. inability to afford social activities, healthy food, clothing etc.

6 | Future trends in housing tenure and the adequacy of retirement income

lower than the before housing costs poverty rate, it was still high in absolute terms

(at 30 per cent) and was the highest of any age group. This reflected the relatively

low mortgage costs across the age cohorts observed at this time. Updating the

analysis using data for 2000, Fahey et al. (2004b) found that the contrast between

before and after housing costs income poverty measures was largest for those

aged over 65: the percentage of persons aged 65+ below the before housing costs

income poverty threshold was 43 per cent, in comparison to 34 per cent when

using the after housing costs measure. These figures have to be interpreted in the

light of the patterns of income poverty across age cohorts at that time; in contrast

to now, older adults (aged 65+) were at the highest risk of (before housing cost)

poverty in the early 2000s, with 43.3 per cent in income poverty in 2000, compared

with 16.9 per cent of the population aged 18-64, and 24.9 per cent of children aged

under 18 (Fahey et al., 2004b).

7

To our knowledge, there has been no research of

after housing costs income poverty in Ireland since the early 2000s, though the CSO

has recently begun to publish such estimates as a supplement to the official

estimates of poverty and deprivation (Central Statistics Office, 2021b).

8

A particularly important aspect in the homeownership debate, and one which has

focused research where younger adults are considered, is the extent to which

saving for homeownership and/or rental payments affects how younger adults

save for retirement. For example, Crawford and Simpson (2020) found that higher

house prices reduced the probability that young adults (aged 21-35) in England,

particularly those working in the public sector and in the middle of the earnings

distribution, enrolled in a private pension, although the magnitude of the effect

was small. Yates and Bradbury (2010) examined the potential for asset-based

welfare

9

to protect households from poverty after retirement by focusing on the

role of homeownership in preventing poverty among older Australians and on

likely future trends in asset accumulation. They found that although asset-based

welfare has the potential to ease the fiscal constraints faced by the state, it may

well lead to poorer social insurance outcomes for households with limited saving

capacity over their lifetime. Using data for Australia (which has high rates of

homeownership), they showed that older households who ‘missed out’ on

homeownership were multiply disadvantaged: they had lower non-housing

wealth, lower disposable incomes and higher housing costs in retirement than

homeowners and they had significantly higher after housing poverty rates.

7

In 2020, children (aged 0-17) had the highest income poverty rate (16.4 per cent) across the age groups, while those

aged 65+ had the lowest (9.8 per cent) (CSO, 2021b).

8

The indicator of after housing costs income is calculated based on an alternative measure of equivalised income,

excluding the total rent paid and mortgage interest. The total rent paid includes housing supports such as the Housing

Assistance Payment (HAP), Rent Supplement, Rental Assistance Scheme (RAS) which were included in the household

income. Any person with an equivalised income after rent and mortgage interest of less than 60 per cent of the median

before rent and mortgage interest is considered at risk of poverty after rent and mortgage interest (i.e. the same

threshold is used for calculating the rate before and after rent and mortgage interest is deducted) (CSO, 2021b).

9

Asset-based welfare refers to the use of policies to incentivise accumulation of asset wealth (including homeownership)

in working life, in order to fund consumption in retirement.

Introduction | 7

Projections suggested that this group will grow in size in the coming decades (see

also Yates et al., 2008).

1.3 CONTRIBUTION AND REPORT STRUCTURE

Given the existing literature, both internationally and for Ireland, there is a clear

gap in terms of research covering the intersection of the changing nature of

housing costs and tenure and the adequacy of income in retirement. The purpose

of this report is to address this gap and to explore the following research questions:

• What is the expected proportion of homeowners and renters in Ireland going

forward?

• What is the typical housing costs burden for these households?

• What implications do projected tenure patterns have for the adequacy of

retirement income, in particular for renters?

More specifically, our contribution is as follows. We build on an existing model of

retirement income adequacy developed at the ESRI to assess the impact of housing

costs on retirement income adequacy. This model, TRIAM, uses data from the Irish

Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA) to simulate the incomes in retirement of a

cohort of individuals born between 1955 and 1960 (who can expect to reach the

state pension age (SPA) of 67 between 2022 and 2027) (Beirne et al., 2020).

10

The

model uses similar data and methods to those used in the UK to assess retirement

income adequacy (Banks et al., 2005; Crawford and O’Dea, 2012). In this model,

the adequacy of retirement income is assessed against a number of poverty line

benchmarks of adequacy. Different definitions of income (i.e. state and

supplementary pension income, adding financial assets, etc.) are also examined.

Cohort-level scenarios of tenure and housing costs are developed using the ESRI’s

micro-simulation tool for assessing housing affordability and tenure (AT-HOME).

This tool considers tenure transitions by households and provides a number of

different scenarios for savings, house prices and incomes to provide housing

tenure proportions. This provides an age-cohort based projection of the share of

renters and homeowners as well as an exploration of the factors that act as the

major barrier to homeownership (for example insufficient savings or income).

These tenure-share projections are incorporated into the TRIAM, coupled with

housing costs estimates for future renters, in a number of stages. In the first stage,

the sensitivity of estimates of retirement income adequacy for the 1955-1960

cohort to the inclusion of housing costs is assessed (i.e. before and after housing

10

When the model was developed (2019), the SPA was expected to increase to 67 from 2021.

8 | Future trends in housing tenure and the adequacy of retirement income

costs measures of poverty are calculated). In the second stage, we assess the

broader implications of projected cohort-level differences in housing tenure and

costs (based on simulations from the AT-HOME model) for before and after

housing costs estimates of poverty. Three estimates of projected homeownership

rates (high, medium and low – based on the AT-HOME modelling results) are used

to illustrate the impact on retirement income adequacy estimates.

The report is structured as follows. Chapter 2 provides a brief overview of the

institutional background and policy context, summarising the current system of

pension payments in Ireland, as well as the key features of the Irish housing

market. Chapter 3 outlines the results of the modelling to derive cohort-specific

tenure and housing costs (from the AT-HOME model), while Chapter 4 presents the

results incorporating these projections into assessments of retirement income

adequacy using TRIAM. The final chapter, Chapter 5, of the report discusses the

findings, drawing out implications for policy.

Policy context | 9

CHAPTER 2

Policy context

2.1 THE IRISH PENSION SYSTEM

In common with many other OECD countries, the Irish pension system comprises

three main pillars: state, occupational and private pensions (Government of

Ireland, 2018; OECD, 2014; 2021). Data from the 2015 and 2016 Survey on Income

and Living Conditions (SILC) show that nearly 75 per cent of the gross income of

those aged 66+ comes from these sources (Nolan et al., 2019). The latest official

figures show that just under two-thirds of those aged 20 to 69 in employment in

2020 were covered by an occupational or private pension (Central Statistics Office,

2021a).

The first pillar comprises the state (contributory or non-contributory) pension,

which is a largely flat-rate payment (i.e. not earnings-related), payable from age

66. Entitlement to the state pension (contributory) is based on a complex set of

rules, and depends on when the individual first entered employment, the number

of pay-related social insurance (PRSI) contributions, and the average number of

contributions per year.

11

To qualify for the non-contributory state welfare pension,

a person must pass a means test based on both income and wealth, and must be

habitually resident in Ireland (Nivakoski and Barrett, 2019).

12

The State Pension Age (SPA) in Ireland is currently 66, with no provision to defer

any entitlement or to claim it earlier. Prior to 2014, the state pension (transition)

in Ireland was payable at age 65 to individuals who retired from insurable

employment and satisfied certain social insurance contribution conditions. The

state pension (transition) was abolished in 2014. In February 2021, a benefit

payment for those aged 65 who have ceased regular employment or self-

employment and who have the required PRSI contributions was introduced.

The benefit is paid at the same rate as the standard rate of Jobseeker’s Benefit

(€208 per week) and stops once the person reaches the SPA of 66.

13

11

It is proposed to move to a new ‘total contributions approach’ (TCA) for determining the level of contributory pension

received by an individual. Under this system, the amount of pensions will be directly proportionate to the number of

social insurance contributions made by a person over his or her working life, rather than the average (Government of

Ireland, 2018). While this was initially intended to be fully rolled out for those retiring in 2020 onwards, those reaching

the SPA are currently being assessed under the existing and TCA systems and given an entitlement corresponding to

the higher of the two.

12

The maximum contributory state pension payable is currently €253.30 per week. The non-contributory state pension

is means-tested and is payable at a maximum rate of €242 for those aged less than 80, and €252 for those aged 80+.

See https://www.citizensinformation.ie/en/social_welfare/social_welfare_payments/older_and_retired_people/ for

further details.

13

See

https://www.citizensinformation.ie/en/social_welfare/social_welfare_payments/older_and_retired_people/paymen

t_for_people_retired_at_65.html for further details.

10 | Future trends in housing tenure and the adequacy of retirement income

For both the contributory and non-contributory state pensions, it was announced

in 2010 that the SPA would further increase to 67 in 2021 and to 68 in 2028

(Government of Ireland, 2010; 2018). However, the planned increase to 67 was

suspended in 2020. The Government established a Commission on Pensions to

examine various issues around the sustainability of the state pension, including the

SPA. The report of the Commission, published in October 2021, recommended that

the SPA increase by three months per year starting from 2028 to reach 67 years in

2031, and at a slower pace (by three months every two years from 2033) to reach

68 in 2039 (Government of Ireland, 2021).

The second pillar comprises occupational pensions, which cover a broad section of

the population.

14

Tax relief at the marginal rate is available for contributions to

approved occupational pension schemes. It is generally not possible to contribute

to an occupational pension scheme after the normal age of retirement. There is no

legal obligation for employers to provide occupational pension schemes, but those

who do not must provide access to at least one Personal Retirement Savings

Account (PRSA). However, public service occupational pension schemes are in

place for staff across the civil service, local authorities, Garda Síochána (Irish

police), the Defence Forces, the health and education sectors and non-commercial

state bodies. In order to increase supplementary pension coverage, particularly in

the private sector, in 2019 the Government announced its intention to introduce a

system of automatic enrolment (OECD, 2021). The details of this Automatic

Enrolment Retirement Savings System were announced in March 2022. From

January 2024, all employees not already in an occupational pension scheme, aged

between 23 and 60 and earning over €20,000 across all of their employments, will

be automatically enrolled. Employer and employee contributions will initially be

1.5 per cent of gross income each (with an additional 0.5 per cent provided by the

State), increasing every three years by 1.5 per cent until they eventually reach 6 per

cent for both employee and employer (and 2 per cent by the State) in year ten

(2034) (Department of Social Protection, 2022).

Finally, the third pillar is a voluntary savings pillar, typically comprised of long-term

personal savings and financial investments used to fund retirement over and above

first and second-pillar arrangements. Private pension schemes are voluntary and

include Retirement Annuity Contracts (RACs), commonly used by the self-

employed, and PRSAs, which were introduced in 2002 as an attempt to increase

the pension coverage among low-coverage employee groups (Nolan et al., 2019).

14

In 2020, two-thirds of workers had an occupational and/or private pension. Of those workers who had an occupational

and/or private pension in 2020, 69.7 per cent had occupational pension cover only (from current or previous

employment), 12.3 per cent had personal pension coverage only and 18 per cent had both (Central Statistics Office,

2021a).

Policy context | 11

The Pensions Roadmap 2018-2023 sets out Government policy in relation to six key

strands of pensions policy, including state pension reform and automatic

enrolment (Government of Ireland, 2018). It recognises that while the state

pension provides basic protection against income poverty in old age, it is not

designed to ensure a high level of retirement income adequacy. Therefore, the

state pension should, in most cases, be combined with supplementary pension

arrangements in the form of occupational and personal pension products. While

international assessments of Ireland’s pension system highlight future

sustainability challenges, particularly if increases to the SPA are deferred

(European Commission, 2021; OECD, 2021), there has been little or no discussion

of the potential impact of cohort-specific changes in housing costs on the

retirement income adequacy of future cohorts.

15

However, in recognition of the

growing importance of housing costs in household budgets, the CSO started to

publish both before and after housing costs measures of income poverty in 2020

(Central Statistics Office, 2021b).

2.2 THE IRISH HOUSING MARKET

Affordability of, and access to, housing has become one of the critical policy issues

in Ireland in the past number of years. This is due to the culmination of worsening

affordability in both rental and house purchase markets as chronic supply

shortages and rising prices have persisted.

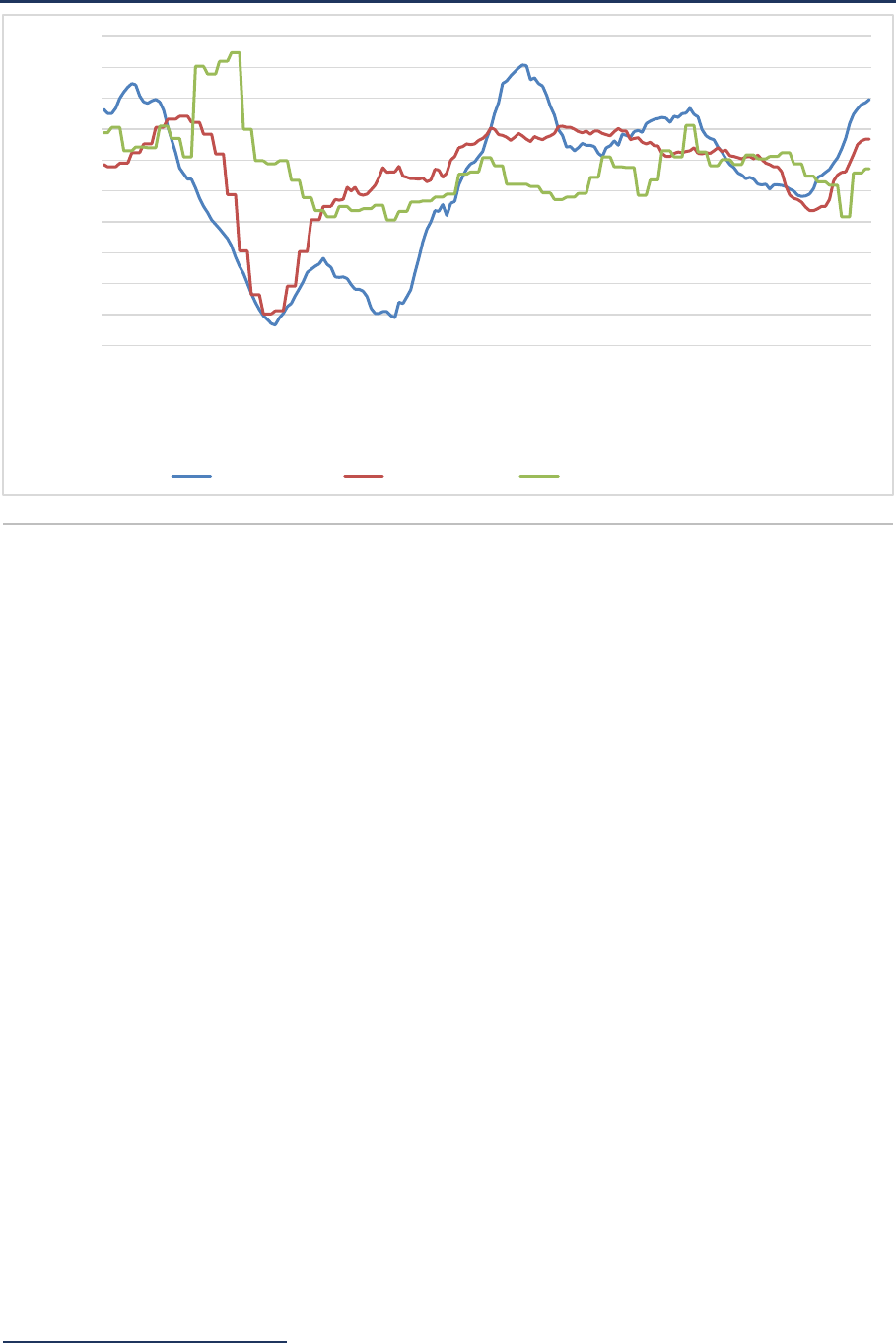

Figure 2.1 documents the trend in housing and rental price changes for the period

2006 to 2022. In the immediate aftermath of the financial crisis, both house prices

and rents dropped considerably reflecting the general economic turmoil of the

period. As the economy began to rebound in 2013/2014, the inflation rate for

housing and rental prices began to recover. In the home purchase market, prices

began to rapidly increase but cooled somewhat in 2015 as the Central Bank of

Ireland introduced a suite of macroprudential mortgage measures which capped

the loan-to-income and loan-to-value ratios for borrowers. The aim of these

measures was to build bank and borrower resilience as well as break the

procyclicality in credit cycles between housing and credit markets (Grace et al.,

2015). House prices began to increase in 2016 and 2017 but tapered off before the

COVID-19 pandemic. Inflationary pressures rebounded in 2021.

15

The European Commission notes that the housing costs overburden rate (1.5 per cent) for the current cohort of over

65s in Ireland is considerably below the EU average (9.8 per cent). The housing costs overburden rate is the share of

older people living in households where the total housing costs represent more than 40 per cent of the total disposable

household income (European Commission, 2021).

12 | Future trends in housing tenure and the adequacy of retirement income

FIGURE 2.1 TRENDS IN HOUSING COSTS (YEAR-ON-YEAR CHANGE, %)

Source: CSO House Price Index and CPI data (rental indicators).

Notes: Percentage change in index over 12 months reported.

While the macroprudential mortgage measures act to limit feedback loops

between credit and house prices,

16

these policies can lead to other externalities

such as tighter access to credit for first time homebuyers. Recent research suggests

that Irish households do face credit access constraints from a lack of sufficient

equity accumulation as well as tight income leverage limits (McQuinn et al., 2021;

Kelly and Mazza, 2019). To attempt to deal with these externalities, a number of

policy supports were introduced into the market such as the Help-to-Buy scheme

which provides for a tax rebate towards house purchase of new homes by first time

buyers and the Rebuilding Ireland Home Loan, a direct local authority loan product

(O’Toole and Slaymaker, 2020). Further measures to deal with credit and leverage

access (in the form of general and local authority specific shared-equity schemes)

are forthcoming as part of the ‘Housing for All’ plan announced in 2021.

17

In the rental sector, prices have also risen rapidly in recent years. The sector has

been accommodating a larger and larger share of the population relative to

historical norms (see Figure 2.2) and this has led to considerable rises in the

average level of rents in the period since 2014. To counteract the rapid inflationary

impulses, rent control policies have been introduced to put a cap on inflation.

These ‘Rent Pressure Zones’ placed limits on the allowable inflation rates per

property for rental tenancies in specific geographic zones (see Coffey et al., 2022).

16

Research has shown that the macroprudential rules have limited house price inflation in Ireland (McQuinn, 2021).

17

See De Burca et al. (2021) for a review of the First Home shared equity scheme.

-25

-20

-15

-10

-5

0

5

10

15

20

25

2006M01

2006M08

2007M03

2007M10

2008M05

2008M12

2009M07

2010M02

2010M09

2011M04

2011M11

2012M06

2013M01

2013M08

2014M03

2014M10

2015M05

2015M12

2016M07

2017M02

2017M09

2018M04

2018M11

2019M06

2020M01

2020M08

2021M03

2021M10

%

House Prices Private Rents Local Authority Rents

Policy context | 13

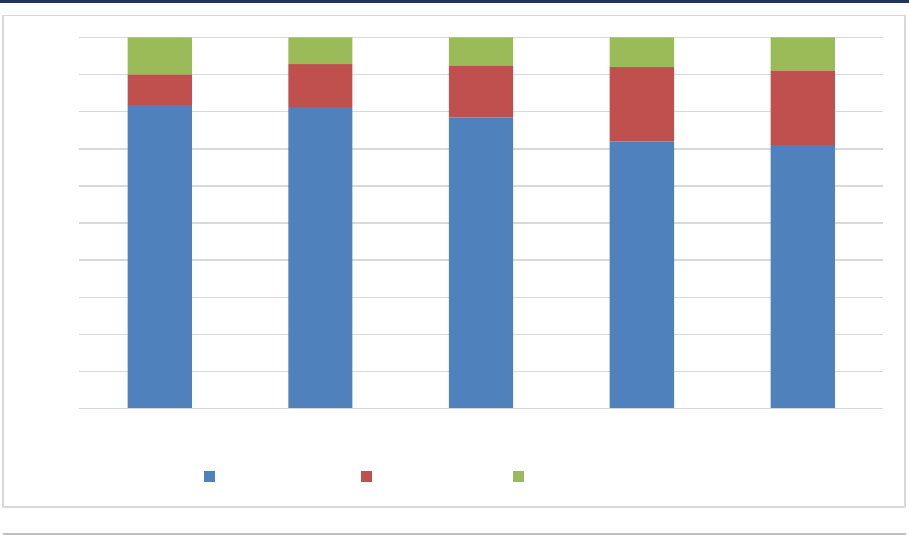

FIGURE 2.2 TENURE SHARES IRELAND

Source: CSO Census of Population, various years.

The inflationary conditions in both the house purchase and rental sectors have

given rise to serious concerns about housing affordability, with a number of

research studies pointing to affordability challenges for subgroups of the

population (low income, urban, private renters) (Corrigan et al., 2019; O’Toole et

al., 2020).

One of the oft-cited reasons behind the rapid price escalation is chronic shortage

of available properties and that new housing completions are well below estimates

of demographic demand (Bergin and Garcia-Rodriguez, 2020). Following the

financial crisis, new housing production in Ireland fell dramatically and has been

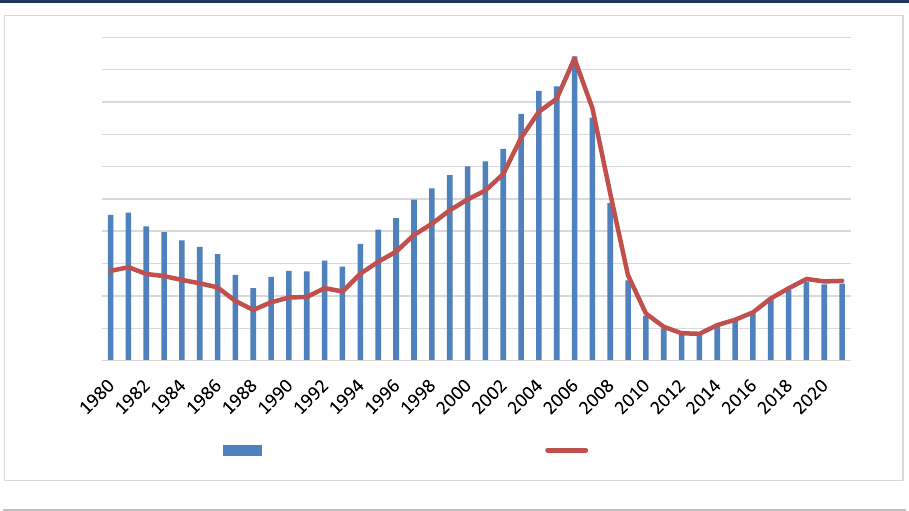

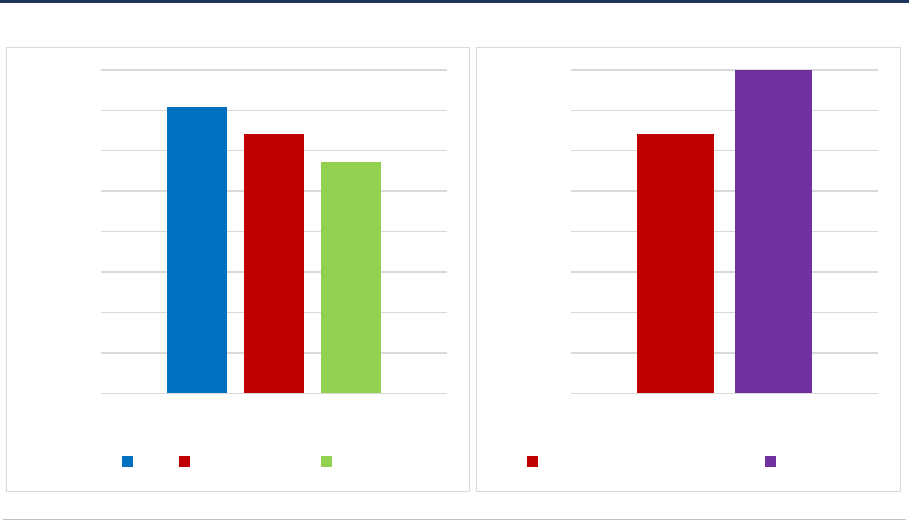

slow to recover as the economy has rebounded. Figure 2.3 displays the total

number of electricity connections in Ireland per year, a proxy for the number of

new housing units (left hand bar). The figure also displays (in red) the number of

completions per 1,000 persons aged 20-50 in the population. Given that this age

bracket is the most likely to provide new forming households, it is a useful proxy

for the demographic pressures coming from this group. Current new supply is well

below the historical levels shown in the data.

A range of policy supports have been introduced in recent years to attempt to

alleviate supply bottlenecks. These policies typically fall into three broad policy

groups: a) those that attempt to deal with the cost of construction such as the site

services fund and the local housing infrastructure activation fund (LIHAF);

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

1991 2002 2006 2011 2016

Own Outright Other Renter Local Authority Renter

14 | Future trends in housing tenure and the adequacy of retirement income

b) policies to provide financing for building projects such as the establishment of

the Land Development Agency (LDA) and Home Building Finance Ireland (HBFI);

and c) policies to lessen time frictions in the planning process. While the number

of housing commencements has recovered in 2021, actual completions continue

to remain below any reasonable estimates of demographic demand.

FIGURE 2.3 HOUSING SUPPLY CHANGES – ESB CONNECTIONS – OVERALL AND PER 1,000

PERSONS AGED 20-50

Source: CSO NDA04 – ESB Connections dataset.

Given these housing challenges, there are a number of more recent and long-

standing policies to deal with affordability for lower-income renters outside the

suite of supports that are aimed at the homeownership transition. The bulk of the

policy support is aimed towards those low-income households whose

circumstances are such that they qualify for social housing provision. For this

population cohort a number of supports are available. First, local authorities

provide accommodation directly to social housing tenants who pay an income-

based differential rent. Subsidies are also provided through the Rental

Accommodation Scheme (RAS) and the Housing Assistance Payment (HAP)

whereby the tenant occupies a property in the private rental sector, but the local

authority pays a top-up to the landlord above the differential rent level (paid by

the tenant). Short-term income support is also available for households through

the Rent Supplement (RS) scheme. A more thorough overview of these schemes

and the mechanisms by which they operate can be found in Doolan et al. (2022)

while a documentation of their evolution overtime is contained in Corrigan and

Watson (2019).

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

0

10,000

20,000

30,000

40,000

50,000

60,000

70,000

80,000

90,000

100,000

Connections per 1000 persons Connections

Housing tenure and cost scenarios | 15

CHAPTER 3

Housing tenure and cost scenarios

Given the housing market context, and the observed lowering of the

homeownership rate in Ireland, consideration must be given as how persistent this

pattern may remain and what the likely implications are for income adequacy in

retirement. Within this context, the purpose of this chapter is threefold. First, we

examine current housing tenure patterns for different age cohorts and how these

have changed over time. Second, we analyse how the proportion of income spent

on housing costs varies across tenures and age groups. Third, we use the ESRI’s

Affordability and Tenure Housing Microsimulation Engine (AT-HOME) tool to

simulate a series of scenarios for homeownership rates for different age cohorts

based on various assumptions around credit access, house prices, incomes and

rental prices. While homeownership may not be the appropriate tenure for certain

households and high levels of homeownership are not necessarily desirable,

homeownership in retirement provides security in the form of low and stable

housing costs, as well as an asset that can be drawn upon as a potential source of

income (Fahey, 2003; Fahey and Norris, 2010). It must be noted that our

assessment of the rate of homeownership focuses on the ability of households to

become homeowners through house purchase and not channels such as whole (or

part) home inheritance. The findings from this chapter will then be used to

examine how housing costs are likely to impact retirement income adequacy for

different age cohorts in Chapter 4.

3.1 HOUSING TENURE

As noted in Chapter 2, the share of homeowners in Ireland has been declining since

2006. To explore this issue in more detail, using data from the Household Budget

Surveys, Figure 3.1 presents the share of homeowners in different age cohorts and

how this has varied over time. Between 1987 and 2004 ownership rates were fairly

stable across the different age groups; rising slightly over the period for the over

35s but falling around 5 percentage points for 25-34s. However, between 2004 and

2015 there was a notable decline in homeownership across those aged 25-64. The

share of 55-64 year olds owning their own home fell nearly 10 percentage points

over this period, while for those aged 35-44, by 2015 it had fallen to 65 per cent,

having fluctuated between 80-85 per cent between 1987 and 2004. The starkest

decline was for the youngest households in our analysis with the share of 25-34s

who owned their own home halving between 2004 and 2015, falling from 60 per

cent to just 30 per cent.

16 | Future trends in housing tenure and the adequacy of retirement income

FIGURE 3.1 % HOMEOWNERS BY AGE COHORT 1987-2015

Source: Authors’ calculations using Household Budget Surveys 1987-2015.

Notes: Homeowners includes both outright owners and owners with a mortgage.

The Household Budget Survey figures presented in Figure 3.1 are only available for

the period up to 2015. The period from 2015 onwards has seen tighter access to

credit with the introduction of macroprudential mortgage regulations, as well as

significant growth in house prices, as shown in Chapter 2. From Figure 3.2, which

uses Survey on Income and Living Conditions (SILC) data for 2018-2019, we see that

the shares of households aged 25-34 and 35-44 who are homeowners have

continued to fall further since 2015, standing at 27 per cent and 58 per cent

respectively for 2018-2019. Ownership rates for those aged 45 and over have

remained similar since 2015.

Regarding the levels of homeownership, Figure 3.2 shows that around 90 per cent

of those in or approaching retirement age (65+) own their own homes. The vast

majority own outright, with fewer than 3 per cent of this age group still making

mortgage payments. Among those who are renting, the majority are in receipt of

some form of housing supports (either living in local authority provided

accommodation or in private sector accommodation with state housing supports).

Fewer than 2 per cent of this cohort live in the private rental sector without

supports. For the subsequent cohort, those currently aged 55-64, the

homeownership rate is around 80 per cent, 10 percentage points lower than the

65+ group. Again, the majority of renters are in receipt of supports, but 5 per cent

of this cohort do live unaided in the private rental sector. The ownership rate for

those aged 45-54 is just under 80 per cent, slightly lower but similar to the 55-64

group. By contrast, far fewer of the subsequent 35-44 cohort are currently

homeowners, with the rate standing at a much lower 58 per cent. For the youngest

cohort (25-34), only 27 per cent currently own their own home, with just over half

of this age group renting unsupported in the private sector.

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

1987 1994 1999 2004 2009 2015

% Homeowners

25-34 35-44 45-54 55-64 65+

Housing tenure and cost scenarios | 17

FIGURE 3.2 % HOUSEHOLDS IN HOUSING TENURES BY AGE COHORT 2018-2019

Source: Authors’ calculations from Survey on Income and Living Conditions (SILC) 2018 and 2019.

Notes: The group ‘rental – with supports’ includes households in in the private rental sector who also report paying rent to a local

authority i.e. HAP or Rental Accommodation Scheme recipients, as well as those living in local authority owned properties.

Households who responded that they are living in their property ‘rent free’ are omitted.

While there may be some degree of homeownership catch-up at later ages,

particularly regarding the youngest age group (in part reflecting increased

education, delayed entry into the workforce and delayed patterns of household

formation), ownership rates for previous birth cohorts have tended to level off by

40-45 (see Figure 1.1). Corlett and Judge (2017) find a similar tapering off of

homeownership rates after 40 in the UK. These findings are consistent with the

fact that banks are typically only willing to offer a mortgage term up to retirement

age and therefore the maximum permissible mortgage term begins to decline after

this point, rendering ownership more challenging.

Corlett and Judge (2017) also find that in the UK both levels and the growth rates

in homeownership between the ages of 30-40 are lower for younger age cohorts.

They conclude the fall in homeownership rates among younger families observed

in the wake of the financial crisis is therefore not likely to fully reverse. Similarly,

Stebbing and Spies-Butcher (2016) find that the rate of catch-up is declining in

Australia and also and conclude that falls in homeownership for younger cohorts

are unlikely to be fully reversed in time. These findings are consistent with Arundel

and Doling (2017) who argue that declines in homeownership are not solely due to

the financial crisis, but that this merely accelerated pre-existing labour market

dynamics such as increased labour market insecurity and are therefore not likely

to be reversed. For Ireland, such a large gap between the ownership rates of the

44-54 and 35-44 groups therefore raises the question of how much this gap is likely

to narrow. We return to this in Section 3.3.1.

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

25-34 35-44 45-54 55-64 65+

%

Rental - Supports

Rental - No Supports

Mortgaged

Own outright

18 | Future trends in housing tenure and the adequacy of retirement income

3.2 CURRENT HOUSING COSTS

A critical issue in the policy considerations around the Irish housing market is the

issue of high housing costs for particular cohorts of the population. Figure 3.3

presents the mean share of net income spent on housing payment costs by tenure

and age cohort. We define housing payment costs as either rental or mortgage

payments. It does not therefore take into account maintenance, insurance and

other costs associated with housing (such as utilities). The high levels of outright

homeownership for those aged 65+, documented above, mean that on average

these homeowners are currently only paying 0.5 per cent of their income on

mortgage costs, as the vast majority have no housing payment costs. The roughly

3 per cent still with a mortgage are paying an average of 22 per cent of net income

on payments, similar to the 21.6 per cent paid by private renters not in receipt of

housing supports. For all other age groups, non-supported private renters are

clearly paying a higher share of income on their housing costs than other tenures.

While mortgaged households typically pay no more than 20-21 per cent on

average, private renters not in receipt of housing supports in the youngest cohort

(25-34), as well as those aged 45-54, are on average paying 27 per cent of their

incomes on rent. In contrast, the housing payment-to-income ratios of local

authority renters are much lower and fairly consistent regardless of age, ranging

from 11-13.5 per cent on average.

FIGURE 3.3 MEAN HOUSING COST-TO-INCOME RATIO (HCTI) % BY TENURE AND AGE COHORT

Source: Authors’ calculations from Survey on Income and Living Conditions (SILC) 2018 and 2019.

Notes: Owner (all) includes both those who own outright and those who are mortgaged homeowners. We omit housing cost-to-income

ratios for supported renters living in private rental sector accommodation due to the difficulties associated with capturing the

rents actually paid by these tenants in SILC (see Doolan et al., 2022, for more information).

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

25-34 35-44 45-54 55-64 65+

Owner (all) Mortgaged PR - no supports LA rent

Housing tenure and cost scenarios | 19

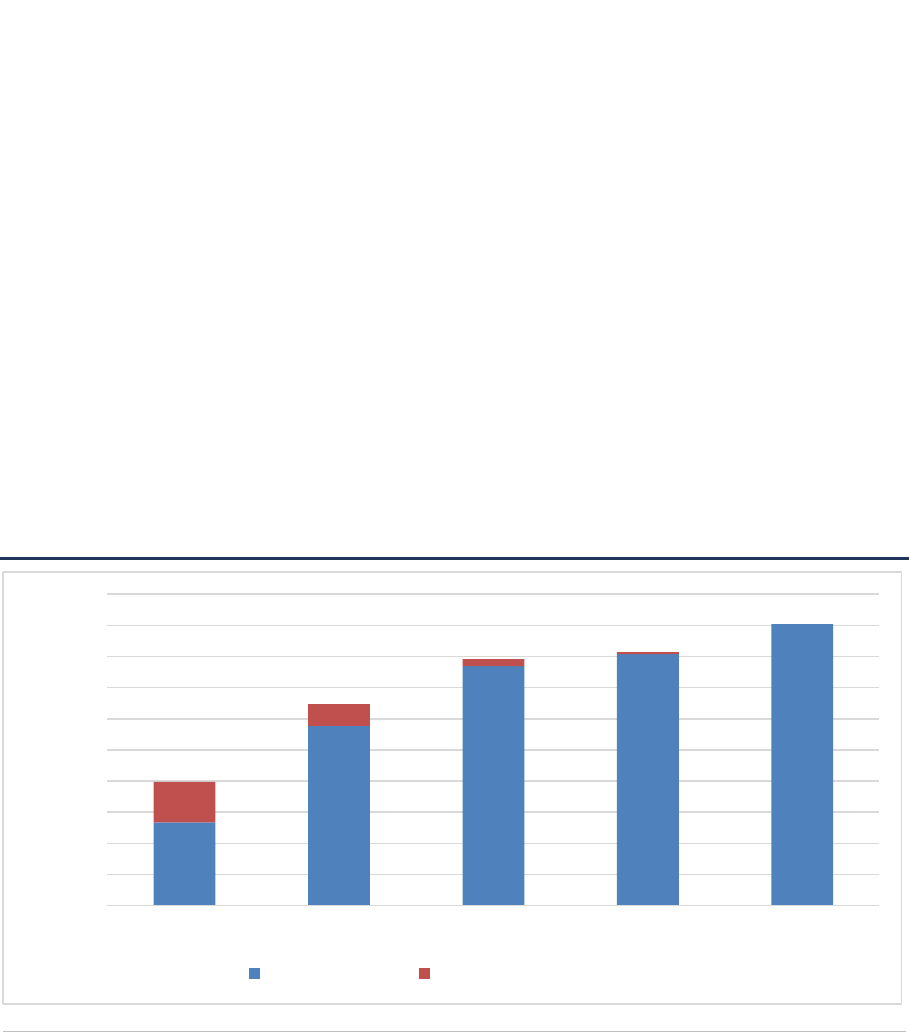

Figure 3.4 presents the share of households in each age cohort faced with high

housing costs. We define high housing costs as having a housing cost-to-income

ratio (HCTI) greater than 30 per cent, a commonly used benchmark for high housing

costs (Corrigan et al., 2019). At present the share of households with high housing

costs clearly falls with age. Just over 1-in-5 households aged 25-34 face high

housing costs under this definition, compared to around 1-in-17 aged 55-64 and

only 1-in-100 of those currently aged 65+. For all age cohorts the incidence of high

housing costs is notably higher for non-homeowners.

FIGURE 3.4 % HOUSEHOLDS WITH HIGH HOUSING COSTS (HCTI>30%) BY AGE COHORT

Source: Survey on Income and Living Conditions (SILC) 2018 and 2019.

Notes: Insufficient observations to report share of non-homeowner households aged 65+ with HCTI>30 per cent. Includes all households

with housing payment costs i.e. all but outright owners.

Figures 3.3 and 3.4 highlight the challenges associated with declining

homeownership rates. As noted, while homeownership may not be the

appropriate tenure for certain households and high levels of homeownership are

not necessarily desirable, homeownership in retirement provides security in the

form of low and stable housing costs, as well as an asset that can be drawn upon

as a potential source of income in retirement. Indeed, as highlighted in Section 1.2,

in the literature homeownership and public pensions are often framed as

substitutes in countries with high rates of homeownership (Delfani et al., 2014).

Additionally, Norris (2016) notes how the Irish welfare system has traditionally

focused on property redistribution, with income redistribution and provision of

state services relegated to a secondary objective. As such, high homeownership in

Ireland may have allowed these households to counteract low public or private

income sources in retirement. If the trends of reduced homeownership outlined

above persist into retirement, a substantial portion of future retirement cohorts

will be faced with housing payment costs in their retirement. We now turn to

modelling the likelihood that current renters in different age groups will be able to

transition into homeownership.

0

5

10

15

20

25

25-34 35-44 45-54 55-64 65+

% Households with HCTI>30%

All Non-Homeowners

20 | Future trends in housing tenure and the adequacy of retirement income

3.3 HOMEOWNERSHIP SIMULATION SCENARIOS

3.3.1 Overview: Affordability and Tenure Housing Microsimulation

Engine (AT-HOME)

Having observed the current tenure structure of Irish households, in this section

we use the Affordability and Tenure Housing Microsimulation Engine (AT-HOME)

outlined in McQuinn et al. (2021) to simulate the likelihood of current rental

households in different age cohorts being able to transition to homeownership

under a prudent credit risk assessment policy and current market conditions and

regulations. This assessment has two stages: (i) determining whether a household

is inherently high credit risk and (ii) an assessment of whether a household could

pass the current credit requirements (such as the macroprudential mortgage

regulations) regarding wealth, income and affordability. For this analysis we

combine the 2018 and 2019 waves of the nationally representative Survey on

Income and Living Conditions (SILC). A diagrammatic overview of our AT-HOME

simulation model is presented in Figure 3.5.

Broadly this can be considered a static style modelling approach in that it uses data

on the incomes, employment characteristics, expenditures and housing costs of

existing households and therefore does not focus on household formation or more

dynamic demographic changes (e.g. migration and birth rates) that will

undoubtedly impact the housing market over time. While these aspects are

important, they are not the focus of this work. Our analysis can therefore be

thought of as assessing the proportion of current households in each age cohort

that are: a) currently homeowners and b) likely to be able to become homeowners.

We focus on five age bands: 25-34; 35-44; 45-54; 55-64; and 65+. We only include

cohorts aged 25 and over in our analysis as we do not model the household

formation process specifically. When interpreting our findings, particularly for this

youngest group aged 25-34, it must however be kept in mind that we are only able

to consider those in each age cohort living independently and not those who

remain in their family home. Eurostat figures suggest around one-in-four 25-34

year olds in Ireland live with their parents.

18

It is important to note that the homeownership simulations presented here are

based on the current market and regulatory conditions. In practice future

homeownership rates could be affected by various policy levers, a greater

provision of social and affordable housing, changes in the availability of policy

supports for homeownership, regulatory changes to private rental sector and

macroprudential regulations, as well as future economic conditions. It must also

be noted that the homeownership transitions that we model in this paper are

18

Available at:

https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/ILC_LVPS08__custom_2353321/default/table?lang=en.

Housing tenure and cost scenarios | 21

concerned solely with those relating to home purchase in the open market. We do

not consider any changes in tenure status that come about due to the inheritance

of whole (or substantial part) properties.