Additional information and materials are available on the Committee’s webpage at:

https://legislature.maine.gov/criminal-records-review-committee-131st-legislature

CRIMINAL RECORDS REVIEW COMMITTEE

Meeting Agenda

Tuesday, July 16, 2024

9:00a.m. – 4:00p.m.

Maine State House, Room 228 (AFA) and via Zoom

Streaming: https://legislature.maine.gov/Audio/#228

1. Welcome and Introductions

• Senator Donna Bailey, Senate Chair

• Speaker Rachel Talbot Ross, House Chair

2. Review of Committee Duties and Interim Study Process

• Office of Policy and Legal Analysis, Staff

3. Update on Outcome of Interim Report Recommendations

• Office of Policy and Legal Analysis, Staff

• Amanda Doherty, Maine Judicial Branch

• Amy McCollett, State Bureau of Identification, DPS

4. Summary of Current Process for Sealing Criminal Records

• Office of Policy and Legal Analysis, Staff

5. Lunch

6. Separation of Powers Issues Related to Clean Slate Legislation

• Derek P. Langhauser, Esq.

7. Requesting an Opinion of the Justices

• Darek M. Grant, Secretary of the Senate

• Robert B. Hunt, Clerk of the House

8. Discussion and Planning for Next Meeting

Future Meetings

Tuesday, August 13, 9:00 a.m. (Hybrid: State House Room 228 and Zoom)

Tuesday, September 24, (Hybrid: State House Room 228 and Zoom)

Tuesday, October 8, (Hybrid: State House Room 228 and Zoom)

Tuesday, November 19, (Hybrid: State House Room 228 and Zoom)

CRIMINAL RECORDS REVIEW COMMITTEE

Established by Resolve 2023, Chapter 103

Membership List

Name

Representation

Senator Donna Bailey,

Senate Chair

Senate member, appointed by the President of the Senate

Speaker Rachel Talbot

Ross, House Chair

House member, appointed by the Speaker of the House

Senator Eric Brakey

Senate member, appointed by the President of the Senate

Representative David

Boyer

House member, appointed by the Speaker of the House

Foster Bates

Representative of a civil right organization whose primary mission

includes the advancement of racial justice, appointed by the

President of the Senate

Anna Welch

Representative of an organization that provides legal assistance on

immigration, appointed by the President of the Senate

Jason Parent

Representative of an organization whose primary mission is to

address issues related to poverty, appointed by the President of the

Senate

Andrea Mancuso

Representative of a statewide nonprofit organization whose mission

includes advocating for victims and survivors or domestic violence,

appointed by the President of the Senate

Tess Parks

Representative of a substance use disorder treatment or recovery

community, appointed by the President of the Senate

Joseph Jackson

Representative of an adult and juvenile prisoner’s rights

organization, appointed by the President of the Senate

Dan MacLeod

Representative of newspaper and other press interests, appointed by

the President of the Senate

Tim Moore

Representative of broadcasting interests, appointed by the Speaker

of the House

Melissa Martin

Representative of a statewide nonprofit organization whose mission

includes advocating for victims and survivors or sexual assault,

appointed by the Speaker of the House

Pedro Vazquez

Representative of an organization that provides free civil legal

assistance to citizens of the State with low incomes, appointed by

the Speaker of the House

Hannah Longley

Representative of a mental health advocacy organization, appointed

by the Speaker of the House

Michael Kebede

Representative of a civil liberties organization whose primary

mission is the protection of civil liberties, appointed by the Speaker

of the House

CRIMINAL RECORDS REVIEW COMMITTEE

Established by Resolve 2023, Chapter 103

Amanda Comeau

Representative of a nonprofit organization whose primary mission is

to advocate for victims and survivors of sexual exploitation and sex

trafficking, appointed by the Speaker of the House

Jill Ward

Representative of an organization involved in advocating for

juvenile justice reform, appointed by the Speaker of the House

Judith Meyer

Representative of a public records access advocacy organization,

appointed by the Speaker of the House

Kent Avery

Attorney General or the Attorney General’s designee

William Montejo

Commissioner of Health and Human Services or the commissioner’s

designee

Amy McCollett

Commissioner of Public Safety or the commissioner’s designee

Samuel Prawer

Commissioner of Corrections or the commissioner’s designee

Maeghan Maloney

President of the Maine Prosecutor’s Association or the president’s

designee

Matthew Morgan

President of the Maine Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers or

the president’s designee

Sheriff Joel Merry

President of the Maine Sheriffs’ Association or the president’s

designee

Chief Jason Moen

President of the Maine Chiefs of Police Association or the

president’s designee

Representative Erin

Sheehan

Chair of the Right to Know Advisory Committee or the chair’s

designee

Amanda Doherty

Member of the Judicial Branch designated by the Chief Justice of

the Supreme Judicial Court

CRIMINAL RECORDS REVIEW COMMITTEE

Member Introductions (2024)

Name Brief Introduction

Senator Donna Bailey,

Senate Chair

Chair, Health Coverage, Insurance and Financial Services Committee and

Member, Judiciary Committee.

Speaker Rachel Talbot

Ross

, House

Chair

Speaker of the House.

Senator Eric Brakey Member, Judiciary Committee.

Representative David

Boyer

Member, Veterans and Legal Affairs Committee. Previously served as the

Marijuana Policy Project’s Maine Director and the campaign manager of

Yes on 1: Regulate and Tax Marijuana, which legalized cannabis in Maine

in 2016.

Foster Bates President, MSP NAACP.

Anna Welch Founding Director of Maine Law’s Refugee and Human Rights Clinic and

Managing Co-Director of the Cumberland Legal Aid Clinic. Through our

student attorneys, we engage in broader advocacy and direct representation

of low-income individuals on criminal, youth, and civil (including

immigration) matters.

Jason Parent Executive Director / Chief Executive Officer, Aroostook County Action

Program (ACAP). ACAP represents vulnerable populations in the rural rim

counties of our state, specifically including customers both in the Aroostook

County Jail and others incarcerated after release to assist with all facets of

community re

-

integration.

Andrea Mancuso Public Policy Director, Maine Coalition to End Domestic Violence.

Tess Parks Policy Organizer, Maine Recovery Advocacy Project (ME-RAP). ME-RAP

is a bipartisan grassroots network dedicated to lifting the voices of people in

recovery through community

-

driven and policy

-

based solutions.

Joseph Jackson Executive Director, Maine Prisoner Advocacy Coalition (MPAC). MPAC

engages in direct action and advocacy with the Maine Department of

Corrections on behalf of incarcerated citizens and their families.

Dan MacLeod Executive Editor, Bangor Daily News.

Tim Moore President / Chief Executive Officer of the Maine Association of

Broadcasters.

Melissa Martin Public Policy and Legal Director at the Maine Coalition Against Sexual

Assault. Represented survivors of sexual violence for many years in civil

legal proceedings prior to joining MECASA.

Pedro Vasquez Pine Tree Legal Assistance. Lifelong human rights defender; serving on

this committee as a representative of an organization that provides free civil

legal assistance to citizens of the State with low incomes.

Hannah Longley

Devon Gross (when

Hannah is

unavailable)

Director of Advocacy and Crisis Intervention, National Alliance on Mental

Illness (NAMI) Maine. Licensed Clinical Social Worker with over 15 years

of clinical experience, collaborating across various facets of the mental

health system, including the intersection of mental health and the criminal

justice system.

Special Project and Data Specialist at NAMI Maine. Devon collaborates

with mental health providers, law enforcement, and community members,

interacts with data related to the mental health system, and actively

CRIMINAL RECORDS REVIEW COMMITTEE

Member Introductions (2024)

advocates for mental health through her involvement in the NAMI Maine

policy team.

Michael Kebede Policy Counsel, ACLU Maine.

Amanda Comeau Director, Survivor Speak USA. Anti-trafficking facilitator, advocate and

mentor who works with women to help them get treatment and find housing.

Jill Ward Director, Center for Youth Policy & Law at Maine Law. Attorney and

advocate with more than 25 years’ experience in juvenile justice reform;

contributed to recent changes to the Maine Juvenile Code around juvenile

record confidentiality and sealing.

Judith Meyer Vice President, Maine Freedom of Information Coalition, a nonprofit entity

that advocates for and educates on public access.

Kent Avery Designee of Attorney General. Assistant Attorney General, Criminal

Division. Previously Assistant District Attorney for seven years and

criminal defense attorney for three years. Currently represents Maine State

Police and Fire Marshal’s Office.

William “Bill”

Montejo

Director, Division of Licensing and Certification, Maine Department of

Health and Human Services.

Amy McCollett Business System Administrator, Department of Public Safety, Maine State

Police, State Bureau of Identification. Gathers and analyzes state and

federal rules and laws in order to properly assist with building, testing and

implementing computer system processes in order to supply Identity History

information (criminal history checks or rap sheets) to the public and law

enforcement communities as required by law.

Samuel Prawer Sam Prawer is the Director of Government Affairs at the Maine Department

of Corrections, serving on the Criminal Records Review Committee as the

Commissioner’s designee.

Maeghan Maloney President, Maine Prosecutors Association and District Attorney for

Kennebec and Somerset counties.

Matthew Morgan President-Elect, Maine Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers (MACDL)

and a practicing criminal defense attorney in both Maine state and federal

courts.

Sheriff Joel Merry Past President, Maine Sheriffs Association and Sheriff of Sagadahoc

County. Has served as Sheriff for 16 years as well as on a number of

committees that have provided reports to the Legislature. Has also worked

with the Administrative Office of the Courts on the issue of fingerprint

compliance for law enforcement agencies.

Chief Jason Moen President, Maine Chiefs of Police Association and Chief of the Auburn

Police Department. Chief Moen has served the City of Auburn for the past

29 years, 6 as Chief. He also serves on several MCOPA committees,

including the Legislative Committee.

Representative Erin

Sheehan

Chair, Right to Know Advisory Committee and Member, Judiciary

Committee

.

Amanda Doherty Manager of Criminal Process & Specialty Dockets, Maine Judicial Branch.

Prior to current position, served as a prosecutor for almost seven years and

in criminal defense for almost a decade before that.

Page 1 - 131LR2256(03)

STATE OF MAINE

_____

IN THE YEAR OF OUR LORD

TWO THOUSAND TWENTY-THREE

_____

H.P. 1047 - L.D. 1622

Resolve, to Reestablish the Criminal Records Review Committee

Sec. 1. Review committee established. Resolved: That the Criminal Records

Review Committee, referred to in this resolve as "the review committee," is established.

Sec. 2. Review committee membership. Resolved: That, notwithstanding Joint

Rule 353, the review committee consists of the following members:

1. Two members of the Senate, appointed by the President of the Senate, including

one member from each of the 2 parties holding the largest number of seats in the

Legislature;

2. Two members of the House of Representatives, appointed by the Speaker of the

House of Representatives, including one member from each of the 2 parties holding the

largest number of seats in the Legislature;

3. The Attorney General or the Attorney General's designee;

4. The Commissioner of Health and Human Services or the commissioner's designee;

5. The Commissioner of Public Safety or the commissioner's designee;

6. The Commissioner of Corrections or the commissioner's designee;

7. The President of the Maine Prosecutors Association or the president's designee;

8. The President of the Maine Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers or the

president's designee;

9. The President of the Maine Sheriffs' Association or the president's designee;

10. The President of the Maine Chiefs of Police Association or the president's

designee;

11. The chair of the Right To Know Advisory Committee or the chair's designee;

12. A representative of a civil rights organization whose primary mission includes the

advancement of racial justice, appointed by the President of the Senate;

13. A representative of an organization that provides legal assistance on immigration,

appointed by the President of the Senate;

LAW WITHOUT

GOVERNOR'S

SIGNATURE

JULY 19, 2023

CHAPTER

103

RESOLVES

Page 2 - 131LR2256(03)

14. A representative of an organization whose primary mission is to address issues

related to poverty, appointed by the President of the Senate;

15. A representative of a statewide nonprofit organization whose mission includes

advocating for victims and survivors of domestic violence, appointed by the President of

the Senate;

16. A representative of a substance use disorder treatment or recovery community,

appointed by the President of the Senate;

17. A representative of an adult and juvenile prisoners' rights organization, appointed

by the President of the Senate;

18. A representative of newspaper and other press interests, appointed by the President

of the Senate;

19. A representative of broadcasting interests, appointed by the Speaker of the House

of Representatives;

20. A representative of a statewide nonprofit organization whose mission includes

advocating for victims and survivors of sexual assault, appointed by the Speaker of the

House of Representatives;

21. A representative of an organization that provides free civil legal assistance to

citizens of the State with low incomes, appointed by the Speaker of the House of

Representatives;

22. A representative of a mental health advocacy organization, appointed by the

Speaker of the House of Representatives;

23. A representative of a civil liberties organization whose primary mission is the

protection of civil liberties, appointed by the Speaker of the House of Representatives;

24. A representative of a nonprofit organization whose primary mission is to advocate

for victims and survivors of sexual exploitation and sex trafficking, appointed by the

Speaker of the House of Representatives;

25. A representative of an organization involved in advocating for juvenile justice

reform, appointed by the Speaker of the House of Representatives; and

26. A representative of a public records access advocacy organization, appointed by

the Speaker of the House of Representatives.

The review committee shall invite the Chief Justice of the Supreme Judicial Court to

designate a member of the judicial branch to serve as a member of the committee.

Sec. 3. Chairs. Resolved: That the first-named Senate member is the Senate chair

and the first-named House of Representatives member is the House chair of the review

committee.

Sec. 4. Appointments; convening of review committee. Resolved: That all

appointments must be made no later than 30 days following the effective date of this

resolve. The appointing authorities shall notify the Executive Director of the Legislative

Council once all appointments have been completed. After appointment of all members,

the chairs shall call and convene the first meeting of the review committee. If 30 days or

more after the effective date of this resolve a majority of but not all appointments have

Page 3 - 131LR2256(03)

been made, the chairs may request authority and the Legislative Council may grant

authority for the review committee to meet and conduct its business.

Sec. 5. Duties. Resolved: That the review committee shall:

1. Review activities in other states that address the expungement, sealing, vacating of

and otherwise limiting public access to criminal records;

2. Consider so-called clean slate legislation options;

3. Consider whether the following convictions should be subject to different treatment:

A. Convictions for conduct that has been decriminalized in this State over the last 10

years and conduct that is currently under consideration for decriminalization;

B. Convictions for conduct that is nonviolent or involves the use of marijuana; and

C. Convictions for conduct that was committed by victims and survivors of sexual

exploitation and sex trafficking;

4. Consider whether there is a time limit after which some or all criminal records

should not be publicly available;

5. Invite comments and suggestions from interested parties, including but not limited

to victim advocates and prison and correctional reform organizations;

6. Review existing information about the harms and benefits of making criminal

records confidential, including the use and dissemination of those records;

7. Invite comments and suggestions concerning the procedures to limit public

accessibility of criminal records;

8. Consider who, if anyone, should continue to have access to criminal records that are

not publicly available;

9. Develop options to manage criminal records; and

10. Review and consider criminal records expungement legislation referred to the Joint

Standing Committee on Judiciary during the 131st Legislature, including, but not limited

to, legislative documents 848, 1550, 1646 and 1789.

Sec. 6. Staff assistance. Resolved: That the Legislative Council shall provide

necessary staffing services to the review committee, except that Legislative Council staff

support is not authorized when the Legislature is in regular or special session.

Sec. 7. Interim report. Resolved: That, no later than December 6, 2023, the

review committee shall submit to the Joint Standing Committee on Judiciary an interim

report that includes, but is not limited to, its findings and recommendations, including

suggested legislation, regarding the expungement, sealing, vacating of and otherwise

limiting public access to criminal records related to convictions for conduct that is

nonviolent or involves the use of marijuana. The joint standing committee may report out

legislation related to the report to the Second Regular Session of the 131st Legislature.

Sec. 8. Final report. Resolved: That, no later than November 6, 2024, the review

committee shall submit to the joint standing committee of the Legislature having

jurisdiction over judiciary matters a final report that includes its findings and

recommendations not included in the interim report, including suggested legislation. The

Page 4 - 131LR2256(03)

joint standing committee may report out legislation related to the report to the 132nd

Legislature in 2025.

Criminal Records Review Committee - 131st

Legislature

(Resolve 2023, c. 103)

2024 Meeting Dates and Materials:

Tuesday, July 16, 2024 at 9:00 a.m., State House Room 228 (AFA)

Livestream available here: https://legislature.maine.gov/Audio/#228

Tuesday, August 13, 2024 at 9:00 a.m., State House Room 228 (AFA)

Tuesday, September 24, 2024 at 9:00 a.m., State House Room 228 (AFA)

Tuesday, October 8, 2024 at 9:00 a.m., State House Room 228 (AFA)

Tuesday, November 19, 2024 at 9:00 a.m., State House Room 228 (AFA)

2023 Meeting Dates and Materials:

Monday, November 13, 2023 at 9:00 a.m., State House, Rm 228 (AFA)

Archived meeting video

Wednesday, November 29, 2023 at 9:00 a.m., State House, Rm 228 (AFA)

Archived meeting video

Monday, December 11, 2023 at 9:00 a.m., State House, Rm 228 (AFA)

Archived meeting video

Interim Criminal Records Review Committee Report (January 2024)

For reference, here is the link to the 2021 Criminal Records Review Committeewebsite.

Please use the following link to subscribe to the interested parties e-mail list for this study:

OtherCommittee Information:

Background Materials

CommitteeMembers(membership will be updated soon)

CommitteeStaff

Janet Stocco, OPLA

Sophia Paddon, OPLA

Janet Stocco and Sophia Paddon may be reached by phone at 207-287-1670 oror by email using the

email addresses linked above.

About Oice of Policy and

Legal Analysis

Committee Materials

Government Evaluation Act

Legislative Digest (bills and

enacted laws)

Legislative Studies

Legislative Study Reports

(Completed Studies)

Major Substantive Rules

Document Search

Maine Government

Executive • Judicial • Agency Rules

Visit the State House

Tour Guide • Accessibility • Security Screening • Directions & Parking

Email

Senate • House • Webmaster

HOME

SENATE ˇ HOUSE ˇ

LEGISLATIVE

OFFICES ˇ

CALENDAR

COMMITTEES ˇ DOCUMENTS ˇ

MEMBER

RESOURCES

EMPLOYEE

RESOURCES

APPORTIONMENT

COMMISSION

CONTACT US

7/8/24, 11:47 AM

Criminal Records Review Committee - 131st Legislature | Maine State Legislature

https://legislature.maine.gov/criminal-records-review-committee-131st-legislature

1/2

CRIMINAL RECORDS REVIEW COMMITTEE

Update on Recommendations from January 2024 Interim Report

Prepared by the Office of Policy and Legal Analysis (July 2024) 1

Recommendation

Outcome

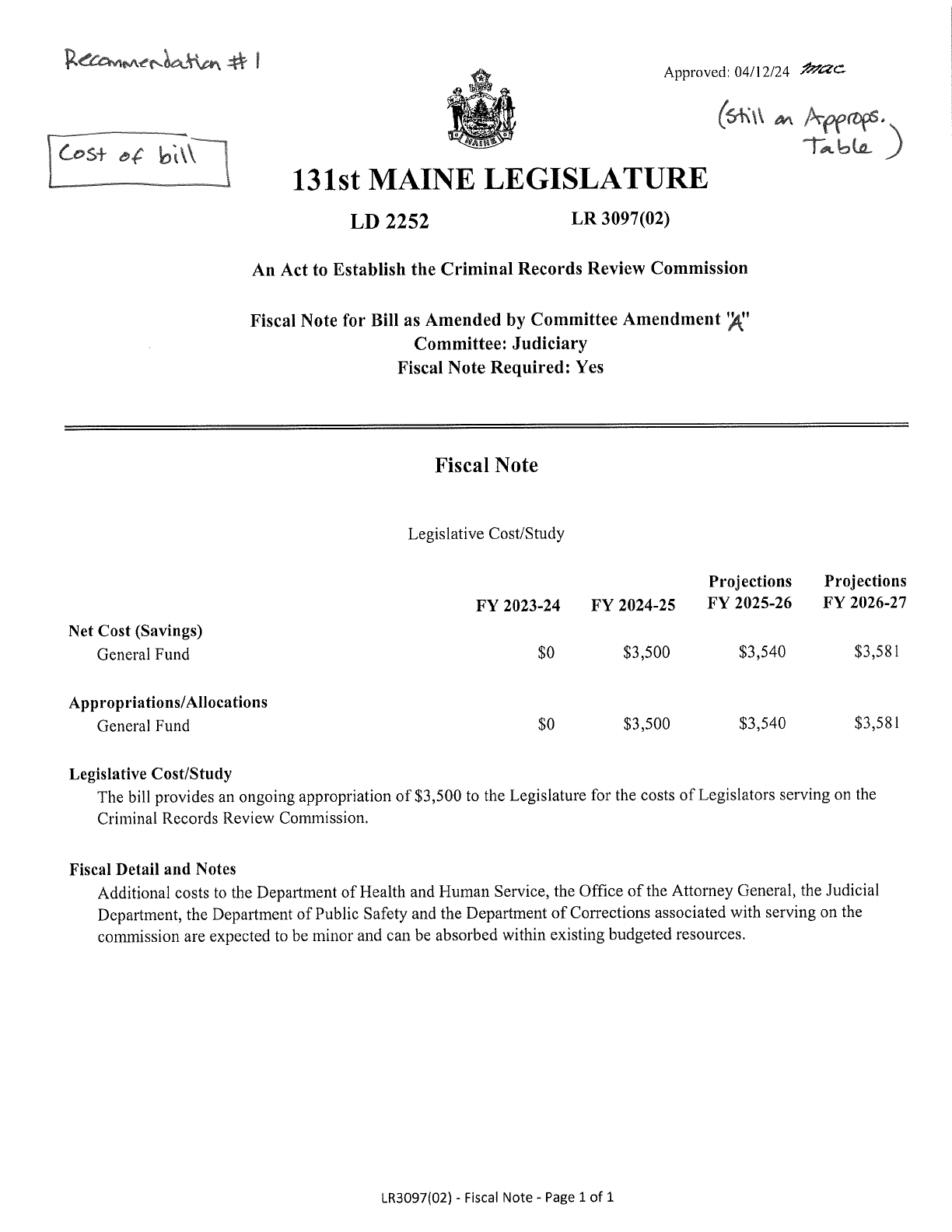

Recommendation 1. Establish a permanent commission based on the Criminal

Records Review Committee. (unanimous of CRRC members voting)

Appendix J to the Interim Report proposed draft legislation to implement this

recommendation by:

• Establishing a permanent Criminal Records Review Commission, with similar

membership to the current CRRC.

• The permanent CRRC would have express authority to (a) submit legislation

relating to criminal history record information at the start of each session and

(b) make recommendations to the Department of Public Safety, Chief Justice

and Advisory Committee on Maine Rules of Unified Criminal Procedure.

Not Met.

The Judiciary Committee introduced and held a public hearing on

L.D. 2252

, An Act to Establish the Criminal Records Review

Commission, which was based on the proposal in Appendix J.

A majority of the Judiciary Committee voted in favor of the bill,

which was amended to fund the cost of Legislators serving on the

committee with an approx. $3,500 per year ongoing General Fund

appropriation. LD 2252 remained on the Special Appropriations

Table when the Second Regular Session of the Legislature

adjourned on May 10, 2024.

Recommendation 2. Establish a process to automatically seal criminal

convictions for Class D and Class E crimes relating to marijuana possession

and cultivation contained in electronic records. (CRRC vote: 15-6; 4 abstained;

4 absent)

Appendix K to the Interim Report proposed draft legislation to implement this

recommendation by:

• Establishing a process to automatically seal convictions for Class D and Class

E crimes related to marijuana possession and cultivation for crimes committed

after Jan. 1, 2001 (when electronic records were in use) but before Jan. 30,

2017 (the effective date of the State’s adult recreational use of cannabis law).

• Automatic sealing would only be available to a defendant not currently facing

criminal charges and only if the defendant had not either been convicted of a

crime or had a criminal charge dismissed as a result of deferred disposition

after fully satisfying the sentence for the most recent conviction to be sealed.

• SBI would be required to examine all criminal history record information in its

files at least monthly to identify convictions potentially eligible for sealing and

transmit that information to the Administrative Office of the Courts. The AOC

would then gather all information in its files related to the identified

convictions and transfer that information to the court of conviction for a

judicial determination whether the conviction qualifies for automatic sealing.

Not Met.

The Judiciary Committee introduced and held a public hearing on

LD 2269

, An Act to Automatically Seal Criminal History Record

Information for Class D and Class E Crimes Relating to

Marijuana Possession and Cultivation , which was based on the

proposal in Appendix K.

A majority of the Judiciary Committee voted that LD 2269 “Ought

Not to Pass.” This recommendation was accepted by both the

Senate and the House of Representatives.

Note: A minority of the Judiciary Committee voted in favor of an

amended version of LD 2269, which tweaked the definition of an

“eligible criminal conviction” to ensure it includes only crimes no

longer considered illegal under Maine’s adult use cannabis laws.

This amended version of the bill was accompanied by a fiscal note

requiring approximately $150,000 in funding to the Department of

Public Safety in the first fiscal year for a paralegal position and

one-time programming costs and approximately $480,000 in

funding to the Judicial Branch in the first fiscal year for 2 limited-

period law clerk positions, active retired judge compensation and

other temporary staffing. If this version of the bill had been

enacted, a portion of these costs would have been ongoing.

CRIMINAL RECORDS REVIEW COMMITTEE

Update on Recommendations from January 2024 Interim Report

Prepared by the Office of Policy and Legal Analysis (July 2024) 2

• The automatic sealing order would have the same effect as an order sealing a

record under the current motion to seal process: The conviction would be

treated as confidential criminal history record information and defendant

would be authorized by law to respond to inquiries from persons other than

criminal justice agencies by not disclosing the existence of the conviction.

Recommendation 3. Add convictions for Class D crimes relating to marijuana

possession and cultivation to the list of eligible criminal convictions for which

a person can submit a motion to seal criminal history record information

related to the conviction. (CRRC vote: 17-3; 6 abstained; 3 absent)

Appendix L to the Interim Report proposed draft legislation to implement this

recommendation by:

• Amending the definition of “eligible criminal conviction” in the law

identifying the types of convictions for which a defendant may file a post-

judgment motion to seal criminal history record information—to newly

include any Class D crime related to unlawfully possessing or cultivating

marijuana that were committed before Jan. 30, 2017, the effective date of the

State’s adult recreational use of cannabis law.

• All other requirements under current law for filing a post-judgment motion to

seal—i.e., defendant has no current pending criminal charges and 4 years have

passed since defendant was discharged with no subsequent criminal

convictions or dismissals as a result of deferred disposition—would apply to

these new Class D convictions.

Met.

The Judiciary Committee introduced and held a public hearing on

LD 2236

, An Act to Expand the List of Crimes Eligible for a Post-

judgment Motion to Seal Criminal History Record Information to

Include Convictions for Possession and Cultivation of Marijuana,

which was based on the proposal in Appendix L.

A majority of the Judiciary Committee voted in favor of an

amended version of LD 2236, which tweaked the definition of

“eligible criminal conviction” to ensure the newly included Class

D crimes include only those crimes no longer considered illegal

under Maine’s adult use cannabis laws.

The amended bill was enacted as Public Law 2023, chapter 639

.

Recommendation 4. Increase public outreach and notifications to qualified

persons for the current post-judgment motion to seal criminal history record

information. (unanimous of CRRC members voting)

The CRRC sent a letter to Chief Justice Stanfill, which is included in Appendix M

to the Interim Report, requesting that the Maine Judicial Branch:

• Revise court form (CR-218), used by defendants filing a post-judgment motion

to seal, to clarify that a defendant is not required to be represented by an

attorney to file the motion.

• Expand public outreach by (a) updating the criminal law and other relevant

sections of the Judicial Branch website to provide information on the post-

(Information on progress toward implementing this

recommendation will be provided by the Maine Judicial Branch

and Department of Public Safety.)

CRIMINAL RECORDS REVIEW COMMITTEE

Update on Recommendations from January 2024 Interim Report

Prepared by the Office of Policy and Legal Analysis (July 2024) 3

judgment motion to seal process and (b) providing information on the process

to criminal defendants and others involved in the judicial system through any

other resources the branch feels appropriate and helpful.

The CRRC sent a letter to Commissioner Sauschuck, which is included in

Appendix N to the Interim Report, requesting that the Department of Public Safety

expand public outreach on the post-judgment motion to seal process by:

• Updating the SBI website to provide general information on the post-judgment

motion to seal process;

• Updating relevant forms and materials used by SBI and provided to convicted

persons informing them of this process; and

• Creating a system whereby individuals seeking their own criminal history

record information (CHRI) are informed they may be eligible to have their

CHRI sealed.

Recommendation 5. Remove the statutory prerequisite that a person must

have been aged 18 to 27 years when they committed the underlying crime in

order to be eligible to have the person’s criminal history record information

sealed. (unanimous of CRRC members voting)

Appendix O to the Interim Report proposed draft legislation to implement this

recommendation by:

• Repealing the requirement that a defendant convicted of a crime must have

been at least 18 years of age but less than 28 years of age at the time the crime

was committed to qualify to file a post-judgment motion to seal the criminal

history record information related to the conviction.

Met.

The Judiciary Committee introduced and held a public hearing on

LD 2218

, An Act to Remove the Age-related Statutory Prerequisite

for Sealing Criminal History Record Information, which was

based on the proposal in Appendix O.

A majority of the Judiciary Committee voted in favor LD 2218

and the bill was enacted as Public Law 2023, chapter 66

6.

Recommendations for further CRRC discussion this year (see Interim Report pages 13-14):

• Examine potential separation of powers issues related to clean slate legislation

• Examine additional options for clean slate legislation, including:

o Who should be eligible for record sealing or expungement—including the types of criminal convictions that may be sealed and other

requirements defendants must meet to qualify for sealing. See Sections 5(3) & (4) of Resolve 2023, chapter 103 (CRRC duties).

CRIMINAL RECORDS REVIEW COMMITTEE

Update on Recommendations from January 2024 Interim Report

Prepared by the Office of Policy and Legal Analysis (July 2024) 4

o Consider Senator Brakey’s suggestion to allow a person convicted of Class E and Class D marijuana possession or cultivation offenses that are

no longer illegal in the State to petition for “expungement” of “personally identifiable information” related to these convictions.

o Clarify the intent of the CRRC with respect to what “sealing,” “expungement” or the selected language means, given that the use of the term

“expunge” in other states’ clean slate laws may not match the layperson’s understanding of these terms.

o Consider the mechanisms for sealing or expunging conviction records and where the relevant records are held—for example, conviction

records may be held not only by SBI but also by courts, law enforcement agencies, licensing agencies and the Department of Corrections.

o Consider that, even if a government record of conviction is sealed or expunged, information regarding the underlying arrest or conviction often

remains available through news media, social media and other sources.

• Examine the collateral consequences of criminal convictions, including, for example, the use (sometimes required by law) of CHRI when individuals

apply for jobs, apartments, benefits or professional licenses.

Note: Additional Relevant Legislation Enacted in 2024.

Public Law 2023, chapter 560 (LD 747), An Act Regarding the Reporting of Adult Name Changes by the Probate Courts to the State Bureau of

Identification (emergency effective March 25, 2024), establishes a uniform process for county probate courts to report adult name change orders to SBI.

• All adults seeking a name change in probate court must undergo a criminal history record check. If the adult is currently on probation, parole or

supervised release or is required to register as a sex offender, there is a rebuttable presumption against granting the name change.

• A probate court may make the name change order confidential if the adult’s interest in confidentiality outweighs the public interest in disclosure.

There is a presumption against making the order confidential if the adult was convicted of a Class D or Class E crime in the past 5 years or a more

serious crime within the past 10 years and the order may not be made confidential if the adult is currently on probation, parole or supervised release or

is required to register as a sex offender.

• Beginning Jan. 1, 2025, probate courts must electronically transmit all adult name change orders to SBI, unless in a particular case the court finds

extraordinary circumstances that a confidential adult name change order should not be transmitted to SBI.

• In response to a request for an adult’s public CHRI, a Maine criminal justice agency may disseminate information associated with each of the adult’s

former and current legal names unless a name change order was made confidential (either through the process above or any other provision of law). If

the name change order is confidential, a Maine criminal justice agency may not disclose to any requester who is not authorized to receive confidential

CHRI either (a) the existence of the name change or(b) any CHRI associated with a legal name of the adult that is not included within the request.

• This law does not affect how an adult must respond to an inquiry about the adult’s past criminal convictions.

Prepared by the Office of Policy and Legal Analysis (July 2024)

Title 15 Chapter 310-A:

POST-JUDGMENT MOTION TO SEAL CRIMINAL HISTORY RECORD

For all Persons

see §2262

The criminal conviction is an eligible

criminal conviction

(Class E crime other than a sexual

assault under Title 17-A, ch 11; or

Beginning 8/9/24 Class D Marijuana

cultivation and possesion offenses

that are no longer illegal)

4 years have passed since the person

has fully satisfied each of the

sentencing alternatives imposed for

the eligible criminal conviction

Has not been convicted of another

crime in ME or had a criminal charge

dismissed as a result of a deferred

disposition since the time the person

fully satisfied all sentencing

alternatives for the eligible conviction

Has not been convicted of a crime in

another jurisdiction since the time the

person fully satisfied all sentencing

alternatives for the eligible conviction

Does not have any presently pending

criminal charges

Until 8/9/24, must have been

between the ages 18-27 when crime

was committed

For persons convicted of engaging in

prostitution under former 17-A M.R.S.A.

§ 853-A

see §2262-A

The criminal conviction is an eligible

criminal conviction

(Class E conviction of 17-A M.R.S.A.

§853-A)

The person has not been convicted

of a violation of Title 17-A, section

852, 853, 853-B or 855 or for

engaging in substantially similar

conduct in another jurisdiction.

•§852: Aggravated Sex Trafficking

•§853: Sex Trafficking

•§853-B: Engaging person for

prostituion

•§855: Commercia Sexual

exploitation of minor or person

with mental disability

At least 1 year has passed since the

person has fully satisfied each of

the sentencing alternatives

imposed for the eligible criminal

conviction

1

Prepared by the Office of Policy and Legal Analysis (July 2024)

Motion and Hearing Process

1. Filing Motion

Motion filed in underlying criminal proceeding, then set for hearing by clerk

2. Hearing

• The person filing has the right to be represented by counsel but is not

entitled to assignment of counsel at state expense

• State represented by prosecutorial office from the underlying proceeding,

or different office under agreement

• Evidence may include testimony, affidavits and reliable hearsay permitted

by the court. Maine Rules of Evidence do not apply.

• Burden on person filing motion to establish by a preponderance of the

evidence they have met the requirements in section 2262 or 2262-A

3. Order & Written Findings

• If person filing motion meets burden, court issues a written order sealing

the CHRI of the eligible criminal conviction that was the subject of the

motion

• If person does not meet burden, court issues order denying motion; such

order must contain written findings of fact supporting the court’s

determination

• A copy of the court's written order must be provided to the person and the

prosecutorial office that represented the State

4. Notification to State Bureau of Investigation

If the court orders the sealing of the CHRI for the eligible criminal conviction

that was the subject of the motion, the court electronically transmits notice

of the court’s order to SBI.

Upon receipt, SBI must promptly amend its records marking the CHRI for that

conviction as “confidential.” SBI shall send notification of compliance with

this subsection to the person's last known address.

2

Prepared by the Office of Policy and Legal Analysis (July 2024)

After the Sealing of a CHRI

Sealed CHRI may not be disclosed by SBI to the public, but a criminal justice agency may,

under the special restrictions in MRSA 15 §2265, disseminate the sealed CHRI to:

• The person who is the subject of the criminal conviction or their designee

• A criminal justice agency for the purpose of the administration of criminal justice

and criminal justice agency employment:

o Use of the sealed CHRI by an attorney for the State or for another

jurisdiction as part of a prosecution of the person for a new crime,

including use in a charging instrument or other public court document and

in open court

o Use of the sealed CHRI as permitted by the Maine Rules of Evidence and to

comply with discovery requirements of the Maine Rules of Civil Procedure

and the Maine Rules of Unified Criminal Procedure

• Secretary of State to ensure compliance with state and federal motor vehicle laws

• The victim or victims of the crime related to the conviction or

o If the victim is a minor, to the parent(s), guardian or legal custodian

o Immediate family member, guardian, legal custodian or attorney

representing the victim if they cannot act on their own behalf due to

death, age, physical or mental disease or disorder, intellectual disability,

etc.

• The Dept. of Professional and Financial Regulation, Bureau of Insurance, Bureau of

Consumer Credit Protection, Bureau of Financial Institutions and Office of

Securities to ensure compliance with applicable parts of the Maine Consumer

Credit Code, and any state or federal requirement to perform criminal background

checks by those agencies

• Licensing agencies conducting criminal history record checks for licensees,

registrants and applicants for licensure or registration

• A financial institution if the financial institution is required by federal or state law,

regulation or rule to conduct a criminal history record check for the position for

which a prospective employee or prospective board member is applying

• An entity that is required by federal or state law to conduct a fingerprint-based

criminal history record check

For the terms of dissemination and use of Confidential Criminal History Record Information

See pg. 10

3

Prepared by the Office of Policy and Legal Analysis (July 2024)

Loss of Eligibility

If a person is convicted of a new crime in Maine or in another jurisdiction, CHRI must be

unsealed. In the event of a new criminal conviction, the person must promptly file a written

notice in the underlying criminal proceeding of the person’s disqualification from eligibility. If

the person fails to file written notice and the court becomes aware of a new criminal conviction,

the court must offer the person an opportunity to request hearing to contest fact of new

conviction.

Notice of New Crime

If the court orders the unsealing of the record under this section, the court shall electronically

transmit notice of the court's order to the Department of Public Safety, Bureau of State Police,

State Bureau of Identification. The State Bureau of Identification upon receipt of the notice shall

promptly amend its records relating to the person's criminal history record information relating to

that criminal conviction to unseal the record. The State Bureau of Identification shall send

notification of compliance with that requirement to the person's last known address.

Requests a Hearing

The person has burden of proving by

clear and convincing evidence that

they have not been convicted of

another crime since having CHRI sealed

➢ If burden satisfied, court issues

written order certifying this

determination. A copy of the

court's written order must be

provided to the person and the

prosecutorial office that

represented the State.

➢ If burden not met, court issues

a written order unsealing the

CHRI, with written findings of

fact

Does Not Request a Hearing

Court shall determine that the person

has not satisfied the burden of proof

and shall find that the person has been

convicted of the new crime and as a

consequence is no longer eligible for

the sealing order

Court shall issue a written order

unsealing the CHRI, with written

findings of fact. A copy of the order

must be provided to the person and

the prosecutorial office that

represented the State.

4

MAINE JUDICIAL BRANCH

ADA Notice: The Maine Judicial Branch complies with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). If you need a reasonable

accommodation, contact the Court Access Coordinator, accessibility@courts.maine.gov, or a court clerk.

Language Services: For language assistance and interpreters, contact a court clerk or [email protected].

CR-218, Rev. 11/22

Page 1 of 1

www.courts.maine.gov

Motion to Seal Criminal History

STATE OF MAINE

“X” the court for filing:

Superior Court District Court

V.

Unified Criminal Docket

County:

Defendant

Location (Town):

Docket No.:

Defendant’s DOB (mm/dd/yyyy):

MOTION TO SEAL CRIMINAL HISTORY

(CRIME COMMITTED BETWEEN AGES 18-27)

15 M.R.S. §§ 2263-2264

Now comes the defendant and moves, pursuant to 15 M.R.S.§ 2263, to seal Defendant’s criminal history. In

support of this motion, Defendant states:

1. Defendant was convicted of the Class E crime of (name of crime)

on (mm/dd/yyyy) . This crime is eligible for sealing under 15 M.R.S. §

2261(6).

2. Defendant’s date of birth is (mm/dd/yyyy) and Defendant’s age at time

of commission of crime was 18-27 years old.

3. It has been at least 4 years since Defendant fully completed the sentence imposed, including any

incarceration, probation, administrative release, license suspension, fine payments, restitution and/or

community service.

4. Defendant has no other adult criminal convictions in Maine and has not had a case dismissed as the

result of a deferred disposition since completing their sentence for this offence.

5. Defendant has no other criminal convictions in another state or jurisdiction since completing their

sentence for this offense.

6. Defendant has no pending criminal charges in Maine or in another jurisdiction.

Defendant moves this Court to order special restrictions on dissemination and use of Defendant’s criminal

history record information relating to Defendant’s prior criminal conviction in this matter.

Date (mm/dd/yyyy):

►

Defendant’s Signature

Defendant’s Attorney and Maine Bar No.

Defendant’s Mailing Address

5

Prepared by the Office of Policy and Legal Analysis (July 2024)

Example Class E Crimes in Maine

Title 17-A – Maine Criminal Code

• § 151 – Criminal conspiracy

▪ where most serious crime that is the object of the conspiracy is a Class E or Class D

crime

• § 152 – Criminal attempt

▪ where the crime is a Class E or Class D crime

• § 353(1)(A) – Theft by unauthorized taking or transfer

▪ where the value of the property is less than or equal to $500, the person is unarmed,

the property stolen is not a firearm or explosive device, and the person does not have

2 or more certain prior convictions

• § 354(1)(A) – Theft by deception

▪ where the value of the property is less than or equal to $500, the person is unarmed,

the property stolen is not a firearm or explosive device, and the person does not have

2 or more certain prior convictions

• § 354-A(1)(A) – Insurance deception

▪ where the value of the property is less than or equal to $500, the person is unarmed,

the property stolen is not a firearm or explosive device, and the person does not have

2 or more certain prior convictions

• § 356-A(1)(A) – Theft of lost, mislaid or mistakenly delivered property

▪ where the value of the property is less than or equal to $500, the person is unarmed,

the property stolen is not a firearm or explosive device, and the person does not have

2 or more certain prior convictions

• § 357(1)(A) – Theft of services

▪ where the value of the services is less than or equal to $500, the person is unarmed,

and the person does not have 2 or more certain prior convictions

• § 358(1)(A) – Theft by misapplication of property

▪ where the value of the property is less than or equal to $500, the person is unarmed,

the property stolen is not a firearm or explosive device, and the person does not have

2 or more certain prior convictions

• § 359(1)(A) – Receiving stolen property

▪ where the value of the property is less than or equal to $500, the person is unarmed,

the property stolen is not a firearm or explosive device, and the person does not have

2 or more certain prior convictions

• § 402(1)(B) – Criminal trespass

▪ Unless the person enters any dwelling place (Class D)

• § 403(1)(A) – Possession or transfer of burglar’s tools

• § 404 – Trespass by motor vehicle

• § 457 – Impersonating a public servant

• § 501-A – Disorderly conduct

• § 502(2)(B) – Failure to disperse

▪ where person is in the immediate vicinity of, and not a participant in, disorderly

conduct

• § 504 – Unlawful assembly

6

Prepared by the Office of Policy and Legal Analysis (July 2024)

• § 505 – Obstructing public ways

• § 506 – Harassment by telephone or by electronic communication devices

▪ Except in situations involving the sending of an image or video of a sexual act where

the recipient is under 14, 14 or 15 and actor is at least 5 years older, or person called

or contacted suffers from a mental disability known to the actor

• § 506-A(1)(A) – Harassment

▪ Except where the person has two or more prior Maine convictions involving the same

victim or the victim’s family (Class C)

• § 512 – Failure to report treatment of a gunshot wound

• § 513 – Maintaining an unprotected well

• § 514 – Abandoning an airtight container

• § 515 – Unlawful prize fighting

• § 516 – Champerty

• § 517 – Creating a police standoff

• § 551 – Bigamy

• § 552 – Nonsupport of dependents

▪ where the value of the property is less than or equal to $500, the person is unarmed,

the property stolen is not a firearm or explosive device, and the person does not have

2 or more certain prior convictions

• § 605 – Improper gifts to public servants

• § 606 – Improper compensation for services

• § 608 – Official Oppression

• § 609 – Misuse of information

• § 704 – Possession of forgery devices

• § 705 – Criminal simulation

▪ Except in certain situations involving altering the make, model or serial number of a

firearm or transporting such firearm

• § 706 – Suppressing recordable instrument

• § 707 – Falsifying private records

• § 708(A)(1) – Negotiating a worthless instrument

▪ Elevated to higher class crimes in certain situations

• § 751-B(1)(A) – Refusing to submit to arrest or detention

▪ Refuses to stop on request or signal of a law enforcement officer.

• § 753 – Hindering apprehension or prosecution

▪ When assisting person charged or liable to be charged with Class E or Class D crime

• § 757-A – Trafficking of tobacco in adult correctional facilities

• § 757-B – Trafficking of alcohol in adult correctional facilities

• § 760 – Failure to report sexual assault of person in custody

• § 853-B(1)(A) – Engaging person for prostitution

• § 854(1)(A)((1))-((2)) – Indecent conduct

• § 907(1)(A) – Possession or transfer of theft devices

• § 1002-A – Criminal use of laser pointers

▪ When is causes a reasonable person to suffer intimidation, annoyance or alarm

• § 1003 – Criminal use of noxious substance

• § 1107(2)(E)-(F) – Unlawful possession of scheduled drugs

7

Prepared by the Office of Policy and Legal Analysis (July 2024)

▪ schedule Y and schedule Z drugs

• § 1111-A – Use of drug paraphernalia (trafficking or furnishing)

▪ Trafficking or furnishing to a person who is at least 16 years of age, or advertising to

promote the sale of drug paraphernalia

• § 1116 – Trafficking or furnishing imitation scheduled drugs

▪ To a person at least 18 years of age

• § 1117 – Cultivating marijuana

▪ Five or fewer plants, unless authorized under Title 22, chapter 558-C or Title 28-B

Title 29-A – Motor Vehicles and Traffic

• § 1954 – Failure to meet dump truck equipment standards

• § 2411 – Operating while license suspended or revoked (OAS)

▪ Exception in certain circumstances depending on the underlying reason for the

suspension (traffic infraction)

• § 2413(1) – Driving to endanger

• § 2414(2) – Refusing to stop for a law enforcement officer

• § 2415 – Operating under foreign license during suspension or revocation (commits OAS)

• § 2417 – Suspended registration

8

Prepared by the Office of Policy and Legal Analysis (July 2024)

Sentencing Alternatives Imposed under 17-A M.R.S.A. § 1502(2)

• Split sentence of imprisonment with probation

• Fine

• Suspended term of imprisonment

• Term of imprisonment

• Fine in addition to other sentencing alternatives

• Community service

• Fine with administrative release

• Suspended term of imprisonment with administrative release

• Split sentence of imprisonment with administrative release

• Term of imprisonment followed by supervised release

• Deferred disposition

• Restitution

• Sanction (for organizations only)

9

Prepared by the Office of Policy and Legal Analysis (July 2024)

Dissemination and Use of Confidential Criminal History Record Information

Title 15 §2265: Sealed Convictions.

A criminal justice agency may disseminate the sealed CHRI to:

• The person who is the subject of the criminal conviction or that person's designee

• A criminal justice agency for the purpose of the administration of criminal justice and

criminal justice agency employment

o Dissemination and use of the criminal history record information relating to the

sealed record by an attorney for the State or for another jurisdiction as part of a

prosecution of the person for a new crime, including use in a charging instrument

or other public court document and in open court

o Dissemination and use of the criminal history record information relating to the

sealed record as permitted by the Maine Rules of Evidence and to comply with

discovery requirements of the Maine Rules of Civil Procedure and the Maine

Rules of Unified Criminal Procedure

• Secretary of State to ensure compliance with state and federal motor vehicle laws

• The victim or victims of the crime related to the conviction or

o If the victim is a minor, to the parent or parents, guardian or legal custodian of the

victim

o an immediate family member, guardian, legal custodian or attorney representing

the victim if they cannot act on the victim's own behalf due to death, age, physical

or mental disease or disorder, intellectual disability or autism or other reason

• The Department of Professional and Financial Regulation, Bureau of Insurance, Bureau

of Consumer Credit Protection, Bureau of Financial Institutions and Office of Securities

to ensure compliance with applicable parts of the Maine Consumer Credit Code, and any

state or federal requirement to perform criminal background checks by those agencies

• Licensing agencies conducting criminal history record checks for licensees, registrants

and applicants for licensure or registration by the agencies

• A financial institution if the financial institution is required by federal or state law,

regulation or rule to conduct a criminal history record check for the position for which a

prospective employee or prospective board member is applying

• An entity that is required by federal or state law to conduct a fingerprint-based criminal

history record check

Title 16 §705: All Confidential CHRI.

A criminal justice agency may disseminate confidential CHRI to:

• Other criminal justice agencies for the purpose of the administration of criminal justice

and criminal justice agency employment

• Any person for any purpose when expressly authorized by a statute, executive order,

court rule, court decision or court order containing language specifically referring to

confidential CHRI

10

Prepared by the Office of Policy and Legal Analysis (July 2024)

• Any person with a specific agreement with a criminal justice agency to provide services

required for the administration of criminal justice or to conduct investigations

determining the employment suitability of prospective law enforcement officers. The

agreement must specifically authorize access to data, limit the use of the data to purposes

for which given, ensure security and confidentiality of the data consistent with this

chapter and provide sanctions for any violation

• Any person for the express purpose of research, evaluation or statistical purposes or

under an agreement with the criminal justice agency. The agreement must specifically

authorize access to data, limit the use of the data to purposes for which given, ensure

security and confidentiality of the data consistent with this chapter and provide sanctions

for any violation

• Any person who makes a specific inquiry to the criminal justice agency as to whether a

named individual was summonsed, arrested or detained or had formal criminal charges

initiated on a specific date.

• The public for the purpose of announcing the fact of a specific disposition that is

confidential criminal history record information within 30 days of the date of occurrence

of that disposition or at any point in time if the person to whom the disposition relates

specifically authorizes that it be made public

• A public entity for purposes of international travel, such as issuing visas and granting of

citizenship

11

MRS Title 15, Chapter 310-A. POST-JUDGMENT MOTION TO SEAL CRIMINAL HISTORY RECORD

Generated

10.30.2023

Chapter 310-A. POST-JUDGMENT MOTION TO SEAL CRIMINAL

HISTORY RECORD

| 1

Updated to reflect legislation

enacted in the Second Regular

Session of the 131

st

Legislature

CHAPTER 310-A

POST-JUDGMENT MOTION TO SEAL CRIMINAL HISTORY RECORD

§2261. Definitions

As used in this chapter, unless the context otherwise indicates, the following terms have the

following meanings. [PL 2021, c. 674, §1 (NEW).]

1. Administration of criminal justice. "Administration of criminal justice" has the same meaning

as in Title 16, section 703, subsection 1.

[PL 2021, c. 674, §1 (NEW).]

2. Another jurisdiction. "Another jurisdiction" has the same meaning as in Title 17‑A, section 2,

subsection 3‑B.

[PL 2021, c. 674, §1 (NEW).]

3. Criminal history record information. "Criminal history record information" has the same

meaning as in Title 16, section 703, subsection 3.

[PL 2021, c. 674, §1 (NEW).]

4. Criminal justice agency. "Criminal justice agency" has the same meaning as in Title 16, section

703, subsection 4.

[PL 2021, c. 674, §1 (NEW).]

5. Dissemination. "Dissemination" has the same meaning as in Title 16, section 703, subsection

6.

[PL 2021, c. 674, §1 (NEW).]

6. Eligible criminal conviction. "Eligible criminal conviction" means a conviction for a current

or former Class E crime, except a conviction for a current or former Class E crime under Title 17‑A,

chapter 11.

[PL 2023, c. 639, §1 (REPEALED & REPLACED).]

6. Eligible criminal conviction. "Eligible criminal conviction" means:

A. A conviction for a current or former Class E crime, except a conviction for a current or former

Class E crime under Title 17-A, chapter 11; and

B. A conviction for a crime when the crime was committed prior to January 30, 2017 for:

(1) Aggravated trafficking, furnishing or cultivation of scheduled drugs under Title 17-A,

former section 1105 when the person was convicted of cultivating scheduled drugs, the

scheduled drug was marijuana and the crime committed was a Class D crime;

(2) Aggravated cultivating of marijuana under Title 17-A, section 1105-D, subsection 1,

paragraph A, subparagraph (4);

(3) Aggravated cultivating of marijuana under Title 17-A, section 1105-D, subsection 1,

paragraph B-1, subparagraph (4);

(4) Aggravated cultivating of marijuana under Title 17-A, section 1105-D, subsection 1,

paragraph D, subparagraph (4); and

(5) Unlawful possession of a scheduled drug under Title 17-A, former section 1107 when that

drug was marijuana and the underlying crime was a Class D crime.

[PL 2023, c. 639, §1 (NEW).]

MRS Title 15, Chapter 310-A. POST-JUDGMENT MOTION TO SEAL CRIMINAL HISTORY RECORD

2 |

Chapter 310-A. POST-JUDGMENT MOTION TO SEAL CRIMINAL

HISTORY RECORD

Generated

10.30.2023

7. Sealed record. "Sealed record" means the criminal history record information relating to a

specific criminal conviction that a court has ordered to be sealed under section 2264.

[PL 2021, c. 674, §1 (NEW).]

SECTION HISTORY

PL 2021, c. 674, §1 (NEW). PL 2023, c. 639, §1 (AMD).

§2262. Statutory prerequisites for sealing criminal history record information

Except as provided in section 2262‑A, criminal history record information relating to a specific

criminal conviction may be sealed under this chapter only if: [PL 2023, c. 409, §1 (AMD).]

1. Eligible criminal conviction. The criminal conviction is an eligible criminal conviction;

[PL 2021, c. 674, §1 (NEW).]

2. Time since sentence fully satisfied. At least 4 years have passed since the person has fully

satisfied each of the sentencing alternatives imposed under Title 17‑A, section 1502, subsection 2 for

the eligible criminal conviction;

[PL 2021, c. 674, §1 (NEW).]

3. Other convictions in this State. The person has not been convicted of another crime in this

State and has not had a criminal charge dismissed as a result of a deferred disposition pursuant to Title

17-A, former chapter 54-F or Title 17‑A, chapter 67, subchapter 4 since the time at which the person

fully satisfied each of the sentencing alternatives imposed under Title 17‑A, section 1502, subsection 2

for the person's most recent eligible criminal conviction up until the time of the order;

[PL 2021, c. 674, §1 (NEW).]

4. Convictions in another jurisdiction. The person has not been convicted of a crime in another

jurisdiction since the time at which the person fully satisfied each of the sentencing alternatives imposed

under Title 17‑A, section 1502, subsection 2 for the person's most recent eligible criminal conviction

up until the time of the order; and

[PL 2021, c. 674, §1 (NEW); P.L. 2023, c. 666, §1 (AMD).]

5. Pending criminal charges. The person does not have any presently pending criminal charges

in this State or in another jurisdiction; and.

[PL 2021, c. 674, §1 (NEW); P.L. 2023, c. 666, §2 (AMD).]

6. Age of person at time of commission. At the time of the commission of the crime underlying

the eligible criminal conviction, the person had in fact attained 18 years of age but had not attained 28

years of age.

[PL 2023, c. 666, §3 (REPEALED).]

SECTION HISTORY

PL 2021, c. 674, §1 (NEW). PL 2023, c. 409, §1 (AMD). PL 2023, c. 666, §§1 to 3 (AMD).

§2262-A. Special statutory prerequisites for sealing criminal history record information related

to engaging in prostitution

Criminal history record information relating to a criminal conviction for engaging in prostitution

under Title 17‑A, former section 853-A must be sealed under this chapter if: [PL 2023, c. 409, §2

(NEW).]

1. Eligible criminal conviction. The criminal conviction is an eligible criminal conviction;

[PL 2023, c. 409, §2 (NEW).]

2. Time since sentence fully satisfied. At least one year has passed since the person has fully

satisfied each of the sentencing alternatives imposed under Title 17‑A, section 1502, subsection 2 for

the eligible criminal conviction; and

MRS Title 15, Chapter 310-A. POST-JUDGMENT MOTION TO SEAL CRIMINAL HISTORY RECORD

Generated

10.30.2023

Chapter 310-A. POST-JUDGMENT MOTION TO SEAL CRIMINAL

HISTORY RECORD

| 3

[PL 2023, c. 409, §2 (NEW).]

3. Other convictions. The person has not been convicted of a violation of Title 17‑A, section 852,

853, 853‑B or 855 or for engaging in substantially similar conduct in another jurisdiction.

[PL 2023, c. 409, §2 (NEW).]

SECTION HISTORY

PL 2023, c. 409, §2 (NEW).

§2263. Motion; persons who may file

A person may file a written motion seeking a court order sealing the person's criminal history record

information relating to a specific criminal conviction in the underlying criminal proceeding based on a

court determination that the person satisfies the statutory prerequisites specified in section 2262 or

2262‑A. The written motion must briefly address each of the statutory prerequisites. [PL 2023, c.

409, §3 (AMD).]

SECTION HISTORY

PL 2021, c. 674, §1 (NEW). PL 2023, c. 409, §3 (AMD).

§2264. Motion and hearing; process

1. Filing motion. A motion filed pursuant to section 2263 must be filed in the underlying criminal

proceeding. After the motion is filed, the clerk shall set the motion for hearing.

[PL 2021, c. 674, §1 (NEW).]

2. Counsel. The person filing a motion pursuant to section 2263 has the right to be represented by

counsel but is not entitled to assignment of counsel at state expense.

[PL 2021, c. 674, §1 (NEW).]

3. Representation of State. The prosecutorial office that represented the State in the underlying

criminal proceeding may represent the State for purposes of this chapter. On a case-by-case basis, a

different prosecutorial office may represent the State on agreement between the 2 prosecutorial offices.

[PL 2021, c. 674, §1 (NEW).]

4. Evidence. The Maine Rules of Evidence do not apply to a hearing on a motion under this

section. Evidence presented by the participants at the hearing may include testimony, affidavits and

other reliable hearsay evidence as permitted by the court.

[PL 2021, c. 674, §1 (NEW).]

5. Hearing; order; written findings. The court shall hold a hearing on a motion filed under this

section. At the conclusion of the hearing, if the court determines that the person who filed the motion

has established by a preponderance of the evidence each of the statutory prerequisites specified in

section 2262 or 2262‑A, the court shall grant the motion and shall issue a written order sealing the

criminal history record information of the eligible criminal conviction that was the subject of the

motion. If, at the conclusion of the hearing, the court determines that the person has not established

one or more of the statutory prerequisites specified in section 2262 or 2262‑A, the court shall issue a

written order denying the motion. The order must contain written findings of fact supporting the court's

determination. A copy of the court's written order must be provided to the person and the prosecutorial

office that represented the State pursuant to subsection 3.

[PL 2023, c. 409, §4 (AMD).]

6. Notice to State Bureau of Identification. If the court issues an order under subsection 5 that

includes the sealing of a criminal conviction maintained by the State Bureau of Identification pursuant

to Title 25, section 1541 and previously transmitted by the court pursuant to Title 25, section 1547, the

court shall electronically transmit notice of the court's order to the Department of Public Safety, Bureau

of State Police, State Bureau of Identification. Upon receipt of the notice, the State Bureau of

MRS Title 15, Chapter 310-A. POST-JUDGMENT MOTION TO SEAL CRIMINAL HISTORY RECORD

4 |

Chapter 310-A. POST-JUDGMENT MOTION TO SEAL CRIMINAL

HISTORY RECORD

Generated

10.30.2023

Identification shall promptly amend its records relating to the person's eligible criminal conviction to

reflect that the criminal history record information relating to that criminal conviction is sealed and that

dissemination is governed by section 2265. The State Bureau of Identification shall send notification

of compliance with this subsection to the person's last known address.

[PL 2021, c. 674, §1 (NEW).]

7. Subsequent new criminal conviction; automatic loss of eligibility; person's duty to notify.

Notwithstanding a court order sealing the criminal history record information pursuant to subsection 5,

if at any time subsequent to the court's order the person is convicted of a new crime in this State or in

another jurisdiction, the criminal history record information must be unsealed.

A. In the event of a new criminal conviction, the person shall promptly file a written notice in the

underlying criminal proceeding of the person's disqualification from eligibility, identifying the new

conviction, including the jurisdiction, court and docket number of the new criminal proceeding. If

the person fails to file the required written notice and the court learns of the existence of the new

criminal conviction, the court shall notify the person of the apparent existence of the new conviction

and offer the person an opportunity to request a hearing to contest the fact of a new conviction. [PL

2021, c. 674, §1 (NEW).]

B. If the person requests a hearing under paragraph A, the court shall, after giving notice to the

person and the appropriate prosecutorial office, hold a hearing. At the hearing, the person has the

burden of proving by clear and convincing evidence that the person has not been convicted of a

crime subsequent to issuance of the sealing order. At the conclusion of the hearing, if the court

determines that the person has not satisfied the burden of proof, it shall find that the person has

been newly convicted of the crime and as a consequence is no longer eligible for the sealing order

and shall issue a written order unsealing the criminal history record information, with written

findings of fact. If, at the conclusion of the hearing, the court determines that the person has

satisfied the burden of proof, it shall find that the person has not been convicted of the new crime

and issue a written order certifying this determination. A copy of the court's written order must be

provided to the person and the prosecutorial office that represented the State. [PL 2021, c. 674,

§1 (NEW).]

C. If the person does not request a hearing under paragraph A, the court shall determine that the

person has not satisfied the burden of proof and the court shall find that the person has been

convicted of the new crime and as a consequence is no longer eligible for the sealing order and

shall issue a written order unsealing the criminal history record information, with written findings

of fact. A copy of the court's written order must be provided to the person and the prosecutorial

office that represented the State. [PL 2021, c. 674, §1 (NEW).]

[PL 2021, c. 674, §1 (NEW).]

8. Notice of new crime. If the court orders the unsealing of the record under this section, the court

shall electronically transmit notice of the court's order to the Department of Public Safety, Bureau of

State Police, State Bureau of Identification. The State Bureau of Identification upon receipt of the

notice shall promptly amend its records relating to the person's criminal history record information

relating to that criminal conviction to unseal the record. The State Bureau of Identification shall send

notification of compliance with that requirement to the person's last known address.

[PL 2021, c. 674, §1 (NEW).]

SECTION HISTORY

PL 2021, c. 674, §1 (NEW). PL 2023, c. 409, §4 (AMD).

§2265. Special restrictions on dissemination and use of criminal history record information

Notwithstanding Title 16, section 704, the criminal history record information relating to a criminal

conviction sealed under section 2264 is confidential, must be treated as confidential criminal history

MRS Title 15, Chapter 310-A. POST-JUDGMENT MOTION TO SEAL CRIMINAL HISTORY RECORD

Generated

10.30.2023

Chapter 310-A. POST-JUDGMENT MOTION TO SEAL CRIMINAL

HISTORY RECORD

| 5

record information for the purposes of dissemination to the public under Title 16, section 705 and may

not be disseminated by a criminal justice agency, whether directly or through any intermediary, except

as provided in Title 16, section 705 and as set out in this section. In addition to the dissemination

authorized by Title 16, section 705, a criminal justice agency may disseminate the sealed criminal

history record information to: [PL 2021, c. 674, §1 (NEW).]

1. Subject of conviction. The person who is the subject of the criminal conviction or that person's

designee;

[PL 2021, c. 674, §1 (NEW).]

2. Criminal justice agency. A criminal justice agency for the purpose of the administration of

criminal justice and criminal justice agency employment. For the purposes of this subsection,

dissemination to a criminal justice agency for the purpose of the administration of criminal justice

includes:

A. Dissemination and use of the criminal history record information relating to the sealed record

by an attorney for the State or for another jurisdiction as part of a prosecution of the person for a

new crime, including use in a charging instrument or other public court document and in open

court; and [PL 2021, c. 674, §1 (NEW).]

B. Dissemination and use of the criminal history record information relating to the sealed record

as permitted by the Maine Rules of Evidence and to comply with discovery requirements of the

Maine Rules of Civil Procedure and the Maine Rules of Unified Criminal Procedure; [PL 2021,

c. 674, §1 (NEW).]

[PL 2021, c. 674, §1 (NEW).]

3. Secretary of State. The Secretary of State to ensure compliance with state and federal motor

vehicle laws;

[PL 2021, c. 674, §1 (NEW).]

4. Victims. The victim or victims of the crime related to the conviction or:

A. If the victim is a minor, to the parent or parents, guardian or legal custodian of the victim; or

[PL 2021, c. 674, §1 (NEW).]

B. If the victim cannot act on the victim's own behalf due to death, age, physical or mental disease

or disorder, intellectual disability or autism or other reason, to an immediate family member,

guardian, legal custodian or attorney representing the victim; [PL 2021, c. 674, §1 (NEW).]

[PL 2021, c. 674, §1 (NEW).]

5. Financial services regulatory agencies. The Department of Professional and Financial

Regulation, Bureau of Insurance, Bureau of Consumer Credit Protection, Bureau of Financial

Institutions and Office of Securities to ensure compliance with Titles 9‑A, 9‑B, 10, 24, 24‑A and 32, as

applicable, and any state or federal requirement to perform criminal background checks by those

agencies;

[PL 2021, c. 674, §1 (NEW).]

6. Professional licensing agencies. Licensing agencies conducting criminal history record checks

for licensees, registrants and applicants for licensure or registration by the agencies; licensing agencies

performing regulatory functions enumerated in Title 5, section 5303, subsection 2; and the State Board

of Veterinary Medicine pursuant to Title 32, chapter 71‑A to conduct a background check for a licensee;

[PL 2021, c. 674, §1 (NEW).]

7. Financial institutions. A financial institution if the financial institution is required by federal

or state law, regulation or rule to conduct a criminal history record check for the position for which a

prospective employee or prospective board member is applying; or

[PL 2021, c. 674, §1 (NEW).]

MRS Title 15, Chapter 310-A. POST-JUDGMENT MOTION TO SEAL CRIMINAL HISTORY RECORD

6 |

Chapter 310-A. POST-JUDGMENT MOTION TO SEAL CRIMINAL

HISTORY RECORD

Generated

10.30.2023