0

Micro Finance in Vietnam:

Three Case Studies

RUTH PUTZEYS

Hanoi, May 2002

1

This study has been prepared as a thesis in the framework of the MSc course Development

Cooperation at the faculty of the Political and Social Sciences at the University of Ghent, Belgium under

the auspices of Prof Patrick Van Damme, in collaboration with the Belgian Technical Cooperation of

Hanoi, Vietnam.

Address for correspondence

Belgian Technical Cooperation

57 Tran Phu Street

Hanoi

tel : 84 - 4 – 733 8761

e-mail: [email protected]

Acknowledgements

First of all, I would like to thank Prof. Patrick Van Damme for his presence and enthusiasm at long

distance. I also thank the staff involved in the case studies, for providing me access to documents and

information and for helping me to understand the reality of the implementation of S&C schemes. I am

particularly grateful to Mr. Kumar Upadhyay and Mr. Koen Everaert from the FAO project, Mr. Romain

Baertsoen and Ms Cao Thi Hong Van from the VBCP project and Mr. Vuong Ngoc Long from the Dairy

project. I also thank Mr. Marcus Leroy from DGIC-Hanoi, for his encouragement during this year.

I greatly recognize the assistance and friendship of the entire BTC staff in Hanoi, especially of Ms.

Phan Thi Tuyet Thanh, from whom I learned a lot about micro finance and most of all, about Vietnam. I

also thank Gert Janssens for his helping hand. In particular I would like to thank Mr. Koen Goekint, Ms.

Krista Verstraelen, Mr. Jean-Christophe Charlier and Ms. Régine Debrabandere.

But above all, I warmly thank Mr. Paul Verlé for his help and for his continuous believe and driving

force.

2

Acknowledgement 1

Table of contents 2

List of abbreviations 4

I. Introduction p 6

II. Micro Finance p 8

1. Definition

2. Principles and best practices of micro finance

• Objectives

• Target

• Small credit and savings

• Group system

• Services

• Savings

• Interest rates and fees

• Management Information Systems

• Administrative efficiency

• Progressive lending

III. Micro Finance in Vietnam p 16

1. Analysis of Poverty in Vietnam p 16

2. Doi Moi p 18

3. Rural Finance p 19

4. Main actors in credit for the poor in Vietnam p

20

4.1. The Formal Finance System

4.1.1. The Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (VBARD)

4.1.2. Vietnam Bank for the Poor (VBP)

4.1.3. People’s Credit Funds (PCFs)

4.1.4. Main problems affecting the Formal Finance System

4.2. The Informal Finance System

4.2.1. Relatives / Friends / Neighbours

4.2.2. Ho / Hui

4.2.3. Moneylenders

4.3. The Semiformal Finance System

IV. Case Studies

1. Case Study I: VBCP project p 30

1.1. Background

1.1.1. Project area

1.1.2. Objectives of the project

1.2. Micro finance scheme

1.2.1. Methodology

1.2.2. Management of the micro finance scheme

1.2.3. S&C scheme

1.2.4. Financial management and monitoring

1.2.5. Results

3

2. Case Study II: FAO project

p 36

2.1. Background

2.1.1. Project area

2.1.2. Objectives of the project

2.2. Rural Finance component

2.2.1. Methodology

2.2.2. Management of the micro finance scheme

2.2.3. S&C scheme

2.2.4. Guarantee Fund

2.2.5. Financial management and monitoring

2.2.6. Results

3. Case Study III: Dairy project

p 45

3.1. Background

3.1.1. Project area

3.1.2. Objective of the project

3.2. Credit component

3.2.1. Methodology

3.2.2. Management of the credit scheme

3.2.3. Credit scheme

3.2.4. Financial management and monitoring

3.2.5. Results

V. Discussion p 52

• Objectives

• Target group

• Group system

• Preparation and design

• Interest rate

• Savings

• Non-financial services

• Relations with the formal sector

• Management Information System

• Legal framework

VI. Conclusion p 62

VII. References p 63

4

List of abbreviations

BADC Belgian Administration for Development Cooperation

BTC Belgian Technical Cooperation

CAMEL Capital adequacy, Asset Quality, Management, Earnings, Liquidity Management

CCMB Commune Credit Management Board

CGAP Consultative Group to Assist the Poorest

DCCU Dairy Cooperative Credit Unit

DFID Department for International Development

DTC Dairy Training Centre

FAO Food and Agriculture Organization

GDP Gross Domestic Production

HCMC Ho Chi Minh City

HDI Human Development Index

HEPR Hunger Elimination and Poverty Reduction Strategy

hh Household

IAS Institute of Agricultural Sciences

IDB Investment Development Bank

I-PRSP Interim - Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper

MIS Management Information System

MOLISA Ministry of Labor, Invalids and Social Affairs

NGO Non-governmental Organization

ODA Official Development Assistance

PC People's Committee

PCF People's Credit Fund

PEARLS A set of ratios and measures used by the World Council of Credit Unions (standing for

Protection, Effective financial structure, Asset quality, Rates of return and cost,

Liquidity and Signs of growth)

PPA Participatory Poverty Assessment

PPMU Project Permanent Management Unit

PPP Purchasing Power Parity

RJSCB Rural Joint Stock Commercial Bank

ROSCA Rotating Savings Credit Association

S&C Savings and Credit

SBV State Bank of Vietnam

SOE State-owned Enterprise

TFF Technical and Financial File

UNDP United Nations Development Program

UNESCO United Nations Education Science Culture Organization

US$ United State dollar

5

VBA Vietnam Bank of Agriculture

VBARD Vietnam Bank of Agriculture and Rural Development

VBCP Vietnamese - Belgian Credit Project

VBP Vietnam Bank for the Poor

VLSS Vietnam Living Standard Survey

VND Vietnamese dong (15,000 VND = 1 US$ in 2002)

VWU Vietnam Women's Union

6

I. Introduction

Poverty alleviation is one of the most important objectives of developing countries. A promising strategy

to reach this objective seems to be access to credit for the poor, so that new opportunities can be

created to improve incomes. Micro finance programmes, which are specifically targeted on the poor,

constitute a major tool for improving the standard of living without creating dependency and encourage

them to take part in the economic process.

The concept of micro finance is not new. Its origin lies in the numerous traditional and informal systems

of credit that have existed in developing economies since centuries. Many of the current micro finance

practices derive from community-based mutual credit transactions that were based on trust, peer-based

non-collateral borrowing and repayment.

Non-governmental organizations (NGO) and international donor organizations see micro finance as a

mean for providing more efficient aid to poor families in rural areas. The money allocated by

governments and donors to specialized intermediaries can be transformed into small credits extended

to the poor, allowing them to develop economic activities. Credit is not regarded as an input but rather

as an engine for growth.

In Vietnam the importance of micro finance in the fight against poverty is recognised by the

government. In the philosophy that poor people should have equal access to credit, the state even

created a special bank with a mandate to provide credit for the poor. In the last decade, all major

multilateral and bilateral donors and numerous NGOs, active in Vietnam, have been involved in micro

finance programmes.

For Belgium too, micro finance is an important tool in its strategy for poverty alleviation. Belgium

finances several projects with a micro finance component in Vietnam. On June 9

th

and 10

th

1998, the

Belgian Administration for Development Cooperation (BADC) in Hanoi, organized, in collaboration with

the Viet Nam Women’s Union, a Workshop on “Projects with a Credit Component in South-East Asia”.

During this workshop, field actors of development cooperation projects in South-East Asia were brought

together to share experiences and reflect on ideas. The majority of such programmes in the region,

supported by Belgium, were represented. They included bilateral, multilateral, NGOs and cooperation

between university programmes. Progress was evaluated and plans were defined.

7

In this study micro finance in Vietnam will be reviewed and the evolution of 3 of the projects presented

during the workshop of 1998, will be monitored and discussed:

• The Vietnamese – Belgian Credit Project: “Strengthening of the institutional capacity of the

Vietnam Women’s Union to manage Credit and Savings Programmes for rural poor women” –

Phase I, hereinafter called "the VBCP project"

• “Participatory Watershed Management in Hoanh Bo District, Quang Ninh Province” – Phase I

This project, hereinafter called "the FAO project"

• “Development of Dairy Support Activities in Southern Vietnam” project, hereinafter called "the

Dairy project"

All three projects have been financed by the Belgian Government. The VBCP project and the dairy

project are bilateral projects between Belgium and Vietnam and have been implemented by BADC and

from April 2000 onwards, by the Belgian Technical Cooperation (BTC). The FAO project has been

implemented by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). The information of the case studies is

based on field visits, project documents (activity report, final reports, evaluation reports,…) and

discussions with project staff and beneficiaries.

8

II. Micro Finance

1. Definition

Micro finance is the provision of a broad range of financial services such as deposits (savings), loans,

payment services, money transfers and insurance to poor and low-income households and their micro-

enterprises.

Micro finance goes beyond the access to and the distribution of money. It enters into the deeper issue

of how money is used, invested and how savings are done. Micro finance is even more than the supply

of financial services. It is a way to give people access to new opportunities. Together with the ability to

increase their income, they receive information and training and learn how to manage their money.

Micro finance therefore also encloses issues as: organizational and operational aspects, leadership

development, trust building, small enterprise management, education and information transfer.

Empowering the people improves their self-confidence and will make them feel more confident to enter

into the economic, social and political life of the society.

1

These non-financial services define the

specific character of micro finance and make micro finance programmes so valuable.

2. Principles and best practices of micro finance

• Objectives

The general objective of most programmes is to tackle poverty but every programmes has its specific

objective(s). Some of the programmes are exclusively concerned with savings and credit. Others have

a S&C component as part of a package (for example: projects of which the S&C scheme is one of the

activities to reach the specific objective), which sometimes is used as an entry point for promoting other

activities (for example in health and family planning, agriculture extension,…). It is important in a

programmes to define the objectives very clearly.

• Target

2

Targeting is directing the credit programmes exclusively on beneficiaries of the programmes,

depending on the specific objectives of programmes. It is important to identify clearly who is part of the

target population, to determine exactly who is eligible to participate in and benefit from the credit

programme. Targeting is essential for creating and maintaining a good credit discipline, which is a

condition for a programmes’ sustainability.

1

European Commission, Micro finance. Methodological considerations, December 2000, p.5.

2

Gibbons David and Wayne Temlinson. The Grameen Trust, Draft Training Manual on Cost-effective Targeting,

June 1995.

9

The provision of micro credit is mainly targeted on 'poor' and non-bankable people, i.e. those people

who have no possibilities to qualify for traditional bank loans. Two categories of poor people can be

distinguished. The so-called 'entrepreneurial poor' are those people who have the capacity to set up

income generating activities that will eventually increase their income. The 'non-entrepreneurial poor'

need direct assistance of by a social network to survive. They have no capacity to start economic

activities because of a lack of personal skills or because they are so destitute that they are in no

position to develop any meaningful economic activity in their living environment.

3

Micro finance is

targeted on the entrepreneurial poor.

Women are a popular target group for micro finance programmes.

4

This is due to several reasons:

• Worldwide women have shown a greater spirit of enterprise, usually take their business

very seriously and make an essential contribution to the economy of developing

countries. Consequently loans to women generally result in a higher repayment rate,

compared to loans attributed to men.

• Women have a much more limited access to credit because they don’t have any assets

to use as collateral for a loan, since assets or land are usually registered on the name

of the husband.

• The income provided by mothers generally has a bigger impact on the well-being of the

entire family unit (nutrition, education,…).

Micro finance doesn’t only improve the women’s financial situation, but there is also a socio-cultural

(their position in the family and society), psychological (increased self-esteem) and political (more

decision making power) impact to be noticed. In this respect, micro finance is a powerful tool for

improving the status of women.

• Small credit and savings

Micro credit is typically the provision of very small loans that are repaid within short periods of time. In

general, the loan size is decided based on the financial capacity of the borrowers to pay back the credit.

A popular and successful philosophy in credit and savings schemes is to start with a small amount of

credit for a first loan cycle in order to check the creditworthiness of the borrower and to provide an

opportunity for the borrowers to practice a business with a small investment amount. With a second

loan demand, the loan amount can be bigger because at that moment, they have learned how to

manage their investments and they have given prove of being creditworthy and reliable. The loan

period is mainly based on the type of investment and the capacity to pay the instalments. A savings

component gives poor people the possibility to deposit very small amounts of savings and helps them

to accumulate a lump sum.

5

3

UNDP, Micro finance and anti-poverty strategies: a donor perspective.

4

BADC, Draft policy document and guidelines concerning the Promotion of Micro-credit in developing countries.

5

Rutherford Stuard, The Poor and their Money, January 1999.

10

• Group system

The compulsory collateral is one of the main obstacles of poor people to have access to the formal

banking and lending system. Micro finance programmes typically provide credit to households who

have few assets that can be used as collateral. Non-formal micro finance systems usually apply the

"group system" as an alternative to have some kind of guarantee to ensure repayment.

The borrowers are organized in solidarity groups, which are the most decentralised level of a micro

finance system. The nature of these groups varies between schemes. They are composed of people

from the same hamlet, friends, or people from the same peer group.

The group members will meet regularly (in most schemes this is weekly or monthly). During those

meetings the proposed loan use of new borrowers will be screened and it will be decided in the group

whether the proposals are acceptable. Once the loan has been given to a borrower, the group will

follow up the profit of the investment made. Repayments are not collected individually, but per group. If

one borrower can’t pay, the group has to take care of the repayment by dividing the debt among the

group members. New loans depend on good repayment rates of the entire group, so that there is an

incentive to timely reimburse instalments of all group members. This leads to social pressure between

group members and functions as a social collateral. In many cases prospective members are asked to

form groups by themselves. By making their own selection of trustworthy individuals, the chances of

having to contribute for other group members diminishes and repayment rates increase.

The group system not only provides a guarantee for repayment, but also reduces the administrative

costs of the scheme. In most cases, the function of group leader rotates yearly. In this way different

members learn how to take the responsibility of leadership, a responsibility they would never have

when lending at a formal bank. The position of group leader gives them the capacity to participate in the

community and to increase their self-esteem by taking an active part in the social activities. Solidarity

groups make the people more involved and responsible and form a channel for the exchange of

information, assistance and advice. Mutual assistance between group members is an easy and cheap

method for the dissemination of knowledge and information.

• Services

Complicated and time-consuming procedures to obtain loans from the formal sector are considered as

a major obstacle for poor people. In many developing countries 'cheap loans' schemes at subsidized

interest rates have been introduced by the formal sector intended to reach the poor. But in practice,

these often don’t reach the poor. Low-income entrepreneurs have shown willingness and ability to pay

interest rates higher than commercial banks for services that fit their needs. It seems that the poor

value access to credit more than the low cost of credit. If people need money, they generally need it

urgently. Just because of the easy access, people often tend to find informal moneylenders more

11

convenient and flexible than formal commercial or state institutions, even if they charge much higher

interest rates.

Therefore, micro finance programmes should be easily accessible. The credit should be ‘nearby’ and

easy and quick to get. But not only the access to credit is important for the borrowers. What they really

need is a combination between financial and non-financial services. These non-financial services

should include information and training.

To reach sustainability, a micro finance institution should attract new clients and maintain the

commitment and participation of existing clients. This means that the financial services being offered

must be designed to meet the needs of the target group. No identical replications of existing schemes

are advisable. A successful experience can be a total failure if copied into another context. To optimise

a programme, a participatory input from the target group is a necessity. If the borrowers cannot identify

themselves with the scheme, their commitment will be very low.

The schemes should have possibilities for personalized services. Not all clients will progress at the

same speed. There should be different loan and savings products for clients of differing abilities and

with different demands. A scheme must be a flexible instrument that easily can be adapted to local

circumstances and demands. Loan and saving products should be checked regularly to see if they still

meet the demand and if necessary new loan or saving products should be introduced.

Programmes and organizations providing credit to low-income groups have to find the balance between

the quality and quantity of credit, the capacity of the poor to utilize the credit in an efficient way, the

local situation and existence of other formal or informal schemes in the region. After the project, the

donor agency will end its input of finances and at that moment the programme should be self-reliant.

• Savings

The integration of a saving component in a micro finance scheme has different functions:

- By linking a saving scheme to the credit scheme, people learn the principles of savings and money

management, and acquire the habit of saving. Savings are a safe guard for households recovering from

poverty to face unexpected events and dramas.

- Savings are a relatively cheap source of funds for a scheme, as the interest rates to attract savings

are usually less than those that have to be paid to borrow funds commercially. With these extra funds,

new borrowers can be attracted, who in their turn generate capital by depositing savings. The

accumulation of capital for loans is of major importance for the sustainability of a programme. There is

a danger that introducing a credit model without a saving mechanism may induce undesirable

dependency on external funds.

12

- Since there is a higher motivation of the borrowers to pay back loans that are partly financed by the

savings of the people of the community, a bigger involvement and as a consequence, a higher

repayment rate can be expected.

- Savings contribute to the accumulation of capital in a community.

6

The savings component of a scheme can be compulsory or voluntarily. It is important that saving

schemes are trustworthy and easily accessible. Regulations and conditions (e.g. interest rates) should

be clearly defined.

• Interest rates and fees

The interest rate has to be high enough to cover all costs.

The nominal interest rate is a public rate announced by any lending institution. However, the nominal

interest rate is often quite different from the effective rate, which is the actual rate a borrower has to pay

for his/her loan, including the operating costs, the financial cost (= cost of fund), service fees and loan

loss provision. This could result in a different real interest rate, to which any lending institution would

pay a careful look.

Real interest rate = Effective rate - inflation rate

To ensure the viability of the scheme, the real interest rate should be a positive figure. To achieve this,

there are ways to increase the effective rate on loans by taking acts on those costs that the borrowers

have to pay.

Micro finance loans are paid in periodic instalments. With each principal repayment, the interest is paid

as well. When using a declining interest rate, the monthly interest is calculated on the outstanding

balance. This means that the interest paid will decline during the loan cycle.

With a flat interest rate, the amount of the monthly interest to be paid is fixed, not taking into account

what the outstanding balance of the loan is. This system is easier to calculate the repayment schedule

and is easier to understand for the borrower. But in fact, the borrower pays more interest than quoted in

the nominal interest rate.

To ensure viability, the minimal sustainable interest rate should be followed according to the following

formula:

13

Operating cost rate + financial cost rate + loan loss rate + capitalization rate

Interest rate = --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 – loan loss

Each of the above factors is presented as a percentage rate, calculated per average outstanding loan

balance.

Operating costs include staff salary and allowance, renting, depreciation, training costs, technical

support, management costs etc. In an effective micro finance institution, operating costs normally

account for between 10 to 25% of average outstanding loans.

Loan loss provision is defined as part of unrecoverable loan. The loan loss rate can be much lower than

a late repayment rate: the former one indicates actual loan written-off and the latter shows that loans

are not repaid in time, which means that a big part of this outstanding loans can be recovered. Previous

experience of an institution in an important factor in forecasting the rate of future loan loss. A micro

finance scheme with a loan loss rate of more than 5% is difficult to be sustainable. For an efficient

scheme, this rate should be around 1% - 2%.

Financial costs: in many donor projects and government programmes, part of the costs are subsidized.

With the provision of a revolving fund, the cost of fund is zero. However, inflation and devaluation in

money exchange should also have to be taken into account.

Capitalisation rate: this rate shows a real net profit a micro finance institution pursues. In fact, such an

accumulation of profit is important. The capital fund a scheme can borrow safely from outside, is limited

by the equity of the institution. The best way to increase the equity are retained profits. It is up to the

management board to decide upon the rate of capitalization. For a long-term development, a

capitalization rate should count for minimum 5% - 15% of average outstanding loans.

• Management Information Systems

Access to timely, accurate, and detailed information on the overall performance of a micro finance

institution is required, if sustainability and self-sufficiency are to be reached. Therefore, Management

Information Systems (MIS) should be introduced in every programme, which is the piloting tool of the

financial institution. They can be manual, computerized through spreadsheet or computerized through

advanced computer-programme software. A cost-effective MIS should generate both financial and

operational information.

7

6

Devereux Stephen and Henry Pares, Credit and savings for development, 1989, p. 16.

7

Gibbons David and Jennifer Meehan, The Microcredit Summit's Challenge: Working Towards Institutional

Financial Self-Sufficiency while Maintaining a Commitment to Serving the Poorest Families, June 2000, p.13.

14

Basic clients’ profile data and financial reporting on the saving and credit activities are important

instruments to monitor the scheme's performances. These data are transformed in ratios which indicate

the performances. They identify problems, help find solutions and serve as an ‘early warning’ to allow

the management team to react to problems in quick and effective way. Several measurement systems

are used. Most schemes follow the PEARLS system, CAMEL system or the prudential ratio of CGAP

system. These 3 systems basically contain the same main categories of indicators: financial

sustainability ratio, operating efficiency ratio and portfolio quality ratio.

8

The most commonly quoted indicators are:

Financial Sustainability Ratios:

- Return on Performing Assets

- Financial Cost Ratio

- Loan Loss Provision Ratio

- Operating Cost Ratio

- Imputed Cost of Capital Ratio

- Donations and Grants Ratio

- Operating Self-Sufficiency

- Financial Self-Sufficiency

Operating Efficiency Ratios:

- Cost per Unit of Money Lent

- Cost per Loan Made

- Number of Active Borrowers per Credit Officer

- Portfolio per Credit Officer

Portfolio Quality Ratios:

- Portfolio in Arrears

- Portfolio at Risk

- Loan Loss Ratio

- Reserve Ratio

8

European Commission, Microfinance. Methodological considerations, December 2000, p. 93.

15

• Administrative efficiency

9

Well-managed micro finance institutions have administration cost rates ranging from 15% to 25%,

regardless the lending methodology. These include aspects such as travel costs, reporting system,

equipment maintenance and salaries.

Salary and salary-related expenses usually represent a significant bulk of total administrative costs.

Staff must perform as productively and efficiently as possible, while maintaining the quality of their

work. Managers should carefully monitor and measure field staff performance and productivity. Two

basic measures are consistently employed to monitor the efficiency of the micro finance institutions field

staff:

• average number of active loan clients per field staff

• average loan portfolio per field staff

Worldwide the best practice indicator for micro finance institutions ranges from 300 to 500 clients per

field staff member, irrespective of the lending methodology (individual, solidarity group, village banking).

The average loan portfolio per field staff is more difficult to generalize as it depends more upon the

lending methodology used, the level of poverty of the borrowers and the local operating environment.

• Progressive lending

10

To reach sustainability and effective results on poverty reduction, a programme should increase the

outstanding loan size and client growth. It is necessary to ensure that an as great proportion of

available funding as possible reaches the hands of the poorest.

But they have to be able to maintain a strong loan portfolio quality (measured by portfolio-at-risk).

Progressive lending, which provides for increasing maximum loan sizes as borrowers progress from

one loan cycle to another, is critical for both poverty-reduction and the attainment of self-reliance. But

the maximum loan size of subsequent lending cycles should be linked to the repayment performance in

the existing cycle. The subsequent loan size declines by a pre-determined amount for each dropped

repayment and after a number of dropped repayments, the borrower is no longer eligible for a

subsequent loan.

9

Gibbons David and Jennifer Meehan, The Microcredit Summit's Challenge: Working Towards Institutional

Financial Self-Sufficiency while Maintaining a Commitment to Serving the Poorest Families, p. 10-11.

16

III. Micro Finance in Vietnam

1. Analysis of Poverty in Vietnam

11

12

Vietnam is considered as a poor country. Based on international standards, 37% of the population in

Vietnam lived below the poverty line in 1998 (defined as less than 128 US$ per capita per year in

1998). The national poverty line determined by the Ministry of labour, Invalids and Social Affairs

(MOLISA) of Vietnam is lower and defined as the income equivalent of buying 15 kg, 20 kg and 25 kg

of rice per month in mountainous and remote, rural and urban areas respectively. However remarkable

progress was obtained in the 90’s, reflected in rising per capita expenditure and in widespread reports

of improvements in broad well being. The proportion of people with per capita expenditures under the

total poverty line has dropped drastically from 58 % in 1992/93 to 37 % in 1997/98 (VLSS 1993 and

1998). The number of people below a ‘food poverty line’ has also declined from 25 % to 15 %. This

indicates that even the very poorest segments of the population have experienced improvements in

their living standards between 1993 and 1998.

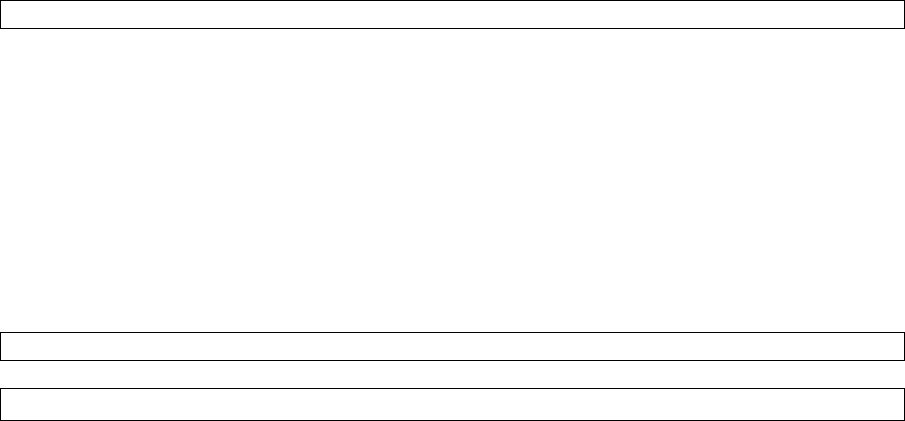

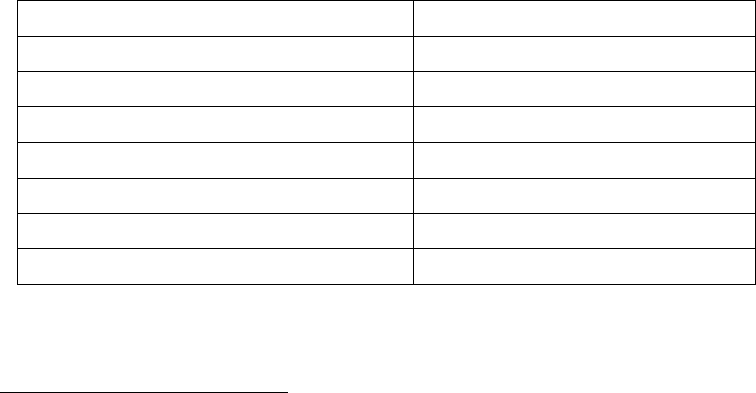

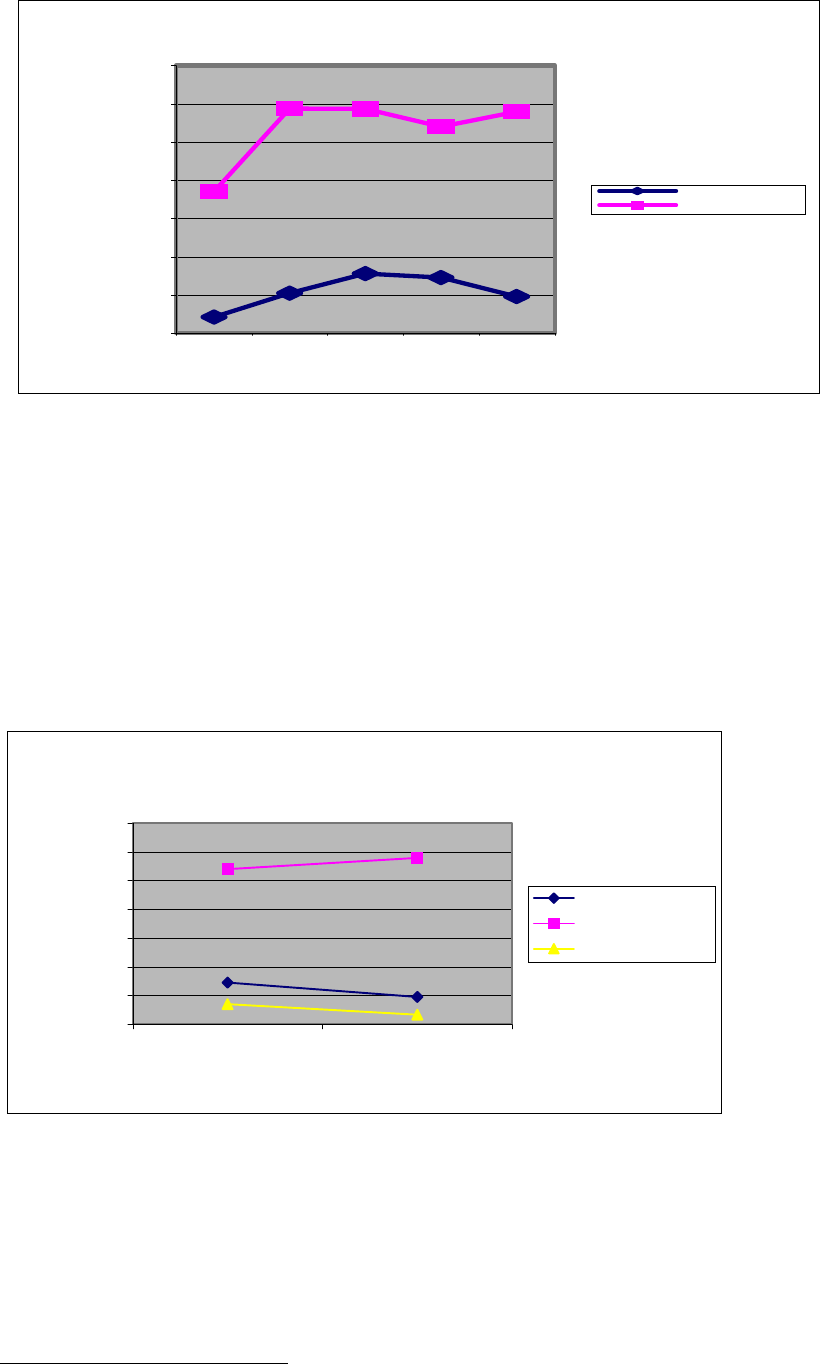

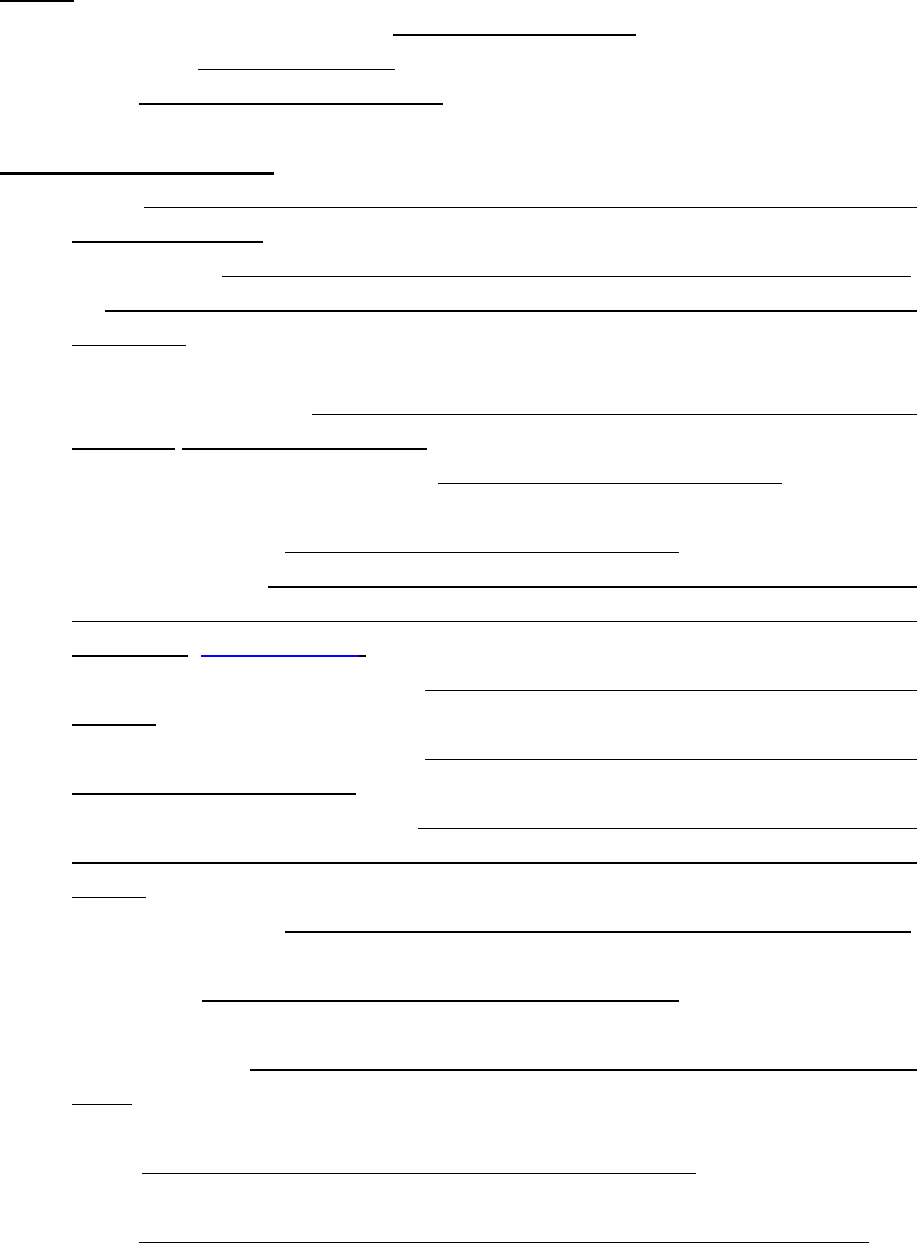

Overall poverty in Vietnam 1993 and 1998

(head count ratio, % of the population)

0

20

40

60

80

Vietnam Urban Rural

%

1993 1998

Figure 1: Poverty reduction during the 1990s

An improvement in social indicators (such as education, child nutrition, adult nutrition, access to

infrastructure and ownership rates of consumer goods) during the period 1993 - 1998 can also been

seen. Several Participatory Poverty Assessments (PPA), clearly show that the poor themselves feel

that their living standards have improved in recent years.

Despite these major improvements, Vietnam remains a poor country with per capita income of around

US$ 380 and a Human Development Index (HDI) value of 0.682 (in 1995 the HDI value was 0.611).

13

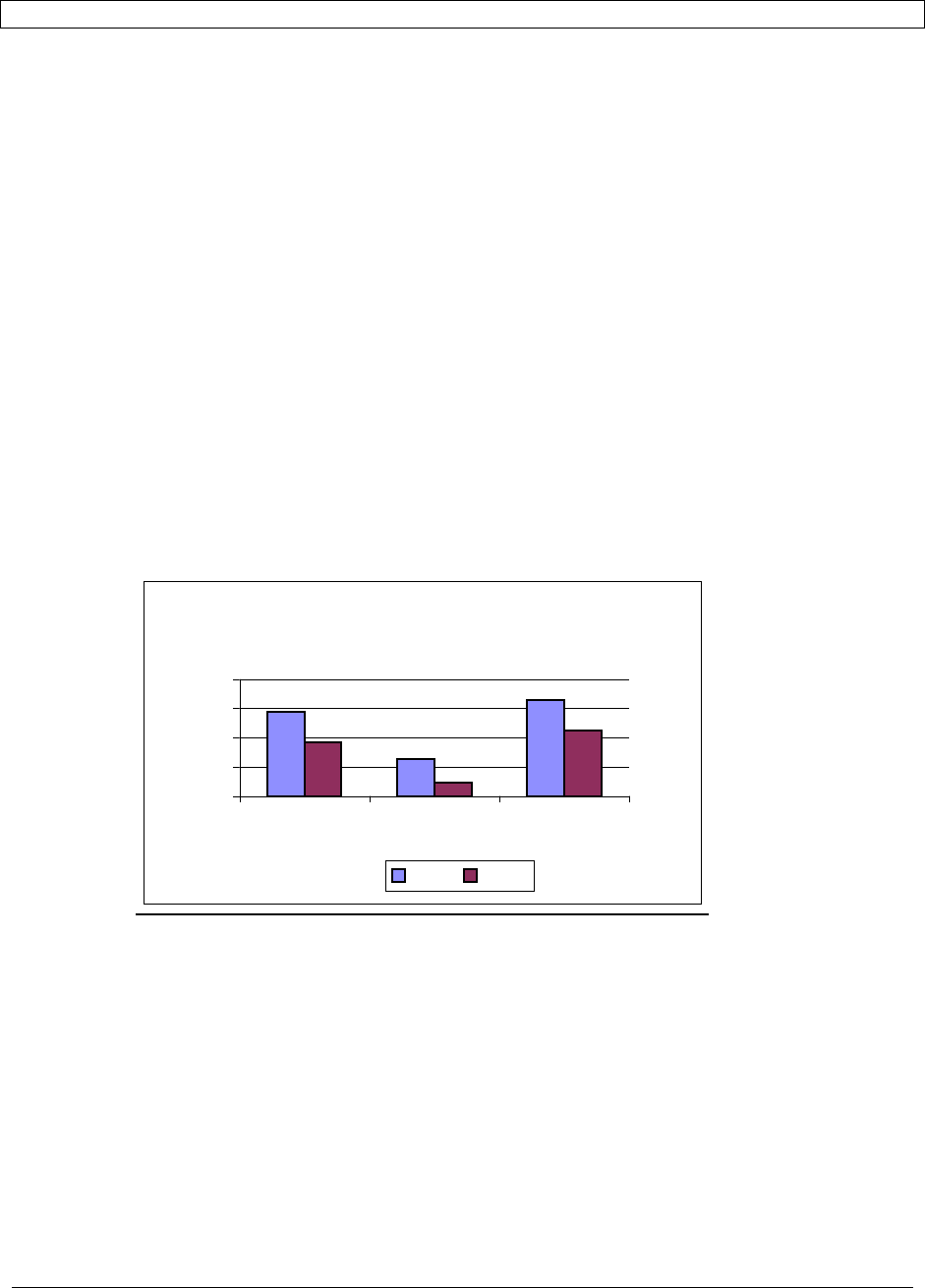

Figure 2 indicates the HDI ranking of the Asian countries.

14

10

Gibbons David and Jennifer Meehan, The Microcredit Summit's Challenge: Working Towards Institutional

Financial Self-Sufficiency while Maintaining a Commitment to Serving the Poorest Families, p. 8-17.

11

Attacking Poverty, Vietnam Development Report 2000, p. 4-17.

12

National Human Development Report 2001, Doi Moi and Human Development in Viet Nam, p. 27-42.

13

UNDP, Human Development Report 2001, p. 140-143.

17

Figure: HDI ranking and GDP for selected countries

1,027

1,361

1,471

1,860

2,248

2,875

3,617

3,805

6,132

8,209

20,767

24,898

22,909

9

26

56

66

70

87

118

24

102

115

101

131

121

0

5,000

10,000

15,000

20,000

25,000

30,000

Japan

Hongkong

Singapore

Malaysia

Thailand

Philippines

China P.R

Indonesia

India

Vietnam

Lao PDR

Cambodia

Myanmar

International $

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

Rank

Real GDP per capita (PPP$) HDI rank

Figure 2: HDI ranking for selected countries

Poverty remains a largely rural phenomenon, with 90 % of the poor living in rural areas, and with 45%

of the rural population living below the poverty line. The drastic gains in poverty reduction in Vietnam

between 1993 and 1998 remain very fragile. A large proportion of individuals are clustered around the

poverty line. This means that it would only take a small reduction in per capita consumption to force

those now living just above the poverty line back below it. If the ‘vulnerable’ are defined as the currently

poor plus those who are near-poor within a line 10 % above the poverty line, then fully 45 % of the

population should be considered vulnerable. Several factors come forward as critical in explaining

people’s vulnerability, most remarkably dependence on little variety of activities and sources of income.

The rural poor are especially vulnerable to risks because they usually lack the assets or access to

credit that provide protection against shocks.

To succeed and to ensure that poverty reduction gains are sustainable and not reversed later, Vietnam

needs to deal with the vulnerability of poverty: both by assisting currently-poor households to escape

from poverty and by protecting households from trends and risks which could force them below the

poverty line again.

As reflected in the Socio-Economic Development Strategy 2001-2010, the Interim Poverty Reduction

Strategy Paper (I-PRSP) and the Hunger Eradication and Poverty Reduction Strategy (HEPR-strategy),

the Government of Vietnam aims to reduce absolute poverty drastically (from 17 per cent in early

14

National Human Development Report 2001, Doi Moi and Human Development in Viet Nam, p. 30.

18

2001 to below 10 per cent in 2005). Given the role of finance for poverty reduction and hunger

alleviation, the Government of Vietnam is, in the framework of the HEPR-strategy, trying to improve

household access to financial services by the provision of subsidized credit, especially for poor and

low-income households.

2. Doi Moi

15

16

17

Before the year 1986, the state controlled all land, natural resources and productive activities in

Vietnam. It allocated equipment and raw materials for production and organized agriculture under a

collective system. It managed the distribution of agricultural products and consumer goods for personal

consumption. In the planned economy, market and prices were not important since prices were set by

the state planning agency at subsidized levels.

This centralized system of management led to severe economic and social problems during the ’70 and

‘80s. In response the 6

th

Party Congress of the Vietnam Communist Party adopted in 1986 a reform

policy in order to move towards a market economy. This reform process, called doi moi, led to the

liberalization of an economic system that had been entirely centrally planned since the mid 1950s. The

de-collectivisation process in agriculture resulted in the re-establishment of private land use rights and

the re-emergence of private farming and private traders in rural areas.

With the adoption of the Land Law in 1988 (Resolution 10), farming in Vietnam is based on a family

farm basis again, and no longer on agricultural production cooperatives. However, private ownership of

agricultural land has not been introduced and all land remains State property. Since 1988, land can be

rented for long-term periods (30 to 50 years) in exchange for paying a tax. In 1993, the Land Law was

revised and now land use rights can be exchanged, transferred, rented, inherited and mortgaged.

However, in many cases land is traded without the official documents, commonly called “Red Book” or

“Red Certificate”. As a result, it turns out that people who do have assets, in fact cannot use them as

collateral.

The country has known a rapid transformation since the adoption of the doi moi policy. Between 1992

and 1998 the average annual GDP growth rate in Vietnam was 8.4 percent. The economic liberalization

in agricultural production resulted in a sharp increase in production output. While up to the 1980's

Vietnam used to be a food importing country, in 1999 it was the second largest rice-exporting nation in

the world. Also the non-farm and wage employment has grown rapidly during 1993-98. A growing

economy like Vietnam’s provides new employment opportunities for its workers. They gradually

move out of agriculture into industry and services. Although generally over the whole of Vietnam, the

share of agriculture in output and employment is declining, for those living in rural areas, agriculture

15

Wolz A., The Transformation of Rural Finance Systems in Vietnam.

16

Kirsch and Ottfried, Vietnam: Agricultural Cooperatives in Transitional Economies.

17

Attacking Poverty, Vietnam Development Report 2000, p. 42.

19

continues to be their main form of employment. Many rural households combine several different forms

of activities and derive incomes from several different sources.

18

The question is whether this spectacular growth in agricultural incomes can be expected to continue in

the future.

19

And to what extent were the gains that agricultural producers have benefited from over the

last five years, a result of a “one-shot” adjustment associated with the move to a market economy?

Some of the problems are:

• Despite the birth control programme (max. 2 children per family and 5 years between the first

and the second child), the population of Vietnam will keep on growing. A lot of the good

agricultural land has already been allocated and only the lower quality land is left over for the

new farm households. This results in over-exploitation of the land and even puts its

sustainability at risk.

• The lack of access to credit that provides protection from risks and shocks.

3. Rural finance

20

21

Before 1988, Vietnam was characterized by a mono-tier banking system (comprising the State Bank of

Vietnam and two specialized institutions, namely the Bank for Investment and Development and the

Bank for Foreign Trade). There was a state monopoly over finance with a widespread subsidy system

with negative real interest rates. This led to a bank crash. Consequently a two-level system has been

developed, consisting of the State Bank of Vietnam (SBV) and four state-owned commercial banks

including the Vietnam Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (VBARD). In 1995 the Vietnam

Bank of the Poor (VBP) was established, a non-profit bank with focus on poverty alleviation. In the

addition joint-venture banks, joint stock banks and People's Credit Funds (PCF) have been created. For

rural households three main institutions are the VBARD, the VBP and the PCFs.

However, the present situation of the rural finance system can only be fully understood if one takes

note of the development of the rural credit cooperatives up to their collapse in the early 1990s. From

1956 on, several Traditional Credit Cooperatives were set up (in the South these were established in

1983). Their main purpose was to gather small deposits and provide credit to individuals, farm

households, small businesses and production cooperatives.

22

Although they were set up as local

financial intermediaries on behalf of the SBV, in reality they were established within small communities

and managed by local People's Committees. Actually the term cooperative did not describe a form of

mutual self-help, but rather reflected an operation, which was organized by the

administration. Most Cooperatives have fallen prey of the financial reforms. As rural collectives went out

of business, their loans from credit cooperatives became non-performing. There was no system of

reserve assets or deposit insurance and the SBV did no longer automatically refinance the credit

18

Attacking Poverty, Vietnam Development Report 2000, p. 41- 57.

19

Attacking Poverty, Vietnam Development Report 2000, p. 53-57.

20

Wolz A., The Transformation of Rural Finance Systems in Vietnam.

21

Kirsch and Ottfried, Vietnam: Agricultural Cooperatives in Transitional Economies.

22

Already in the early 1930s about 5,500 rural credit cooperatives had become operational, another 2,000 were

set-up during the early 1980's. In the late 1980s there were 7,180 credit cooperatives.

20

cooperatives as it used to do before the banking reform of 1988. Most of the rural credit cooperatives

collapsed. Small private enterprises – in many cases newly established – were particularly affected by

the collapse of the credit. At that time these cooperatives were their only source of formal credit.

The collapse of the credit cooperatives had a major effect on the people's faith in the financial system,

including the formal banking system. Many people withdrew their deposits to buy gold and dollars. Until

now people have a profound mistrust in the banking system.

4. Main actors in Credit for the poor in Vietnam

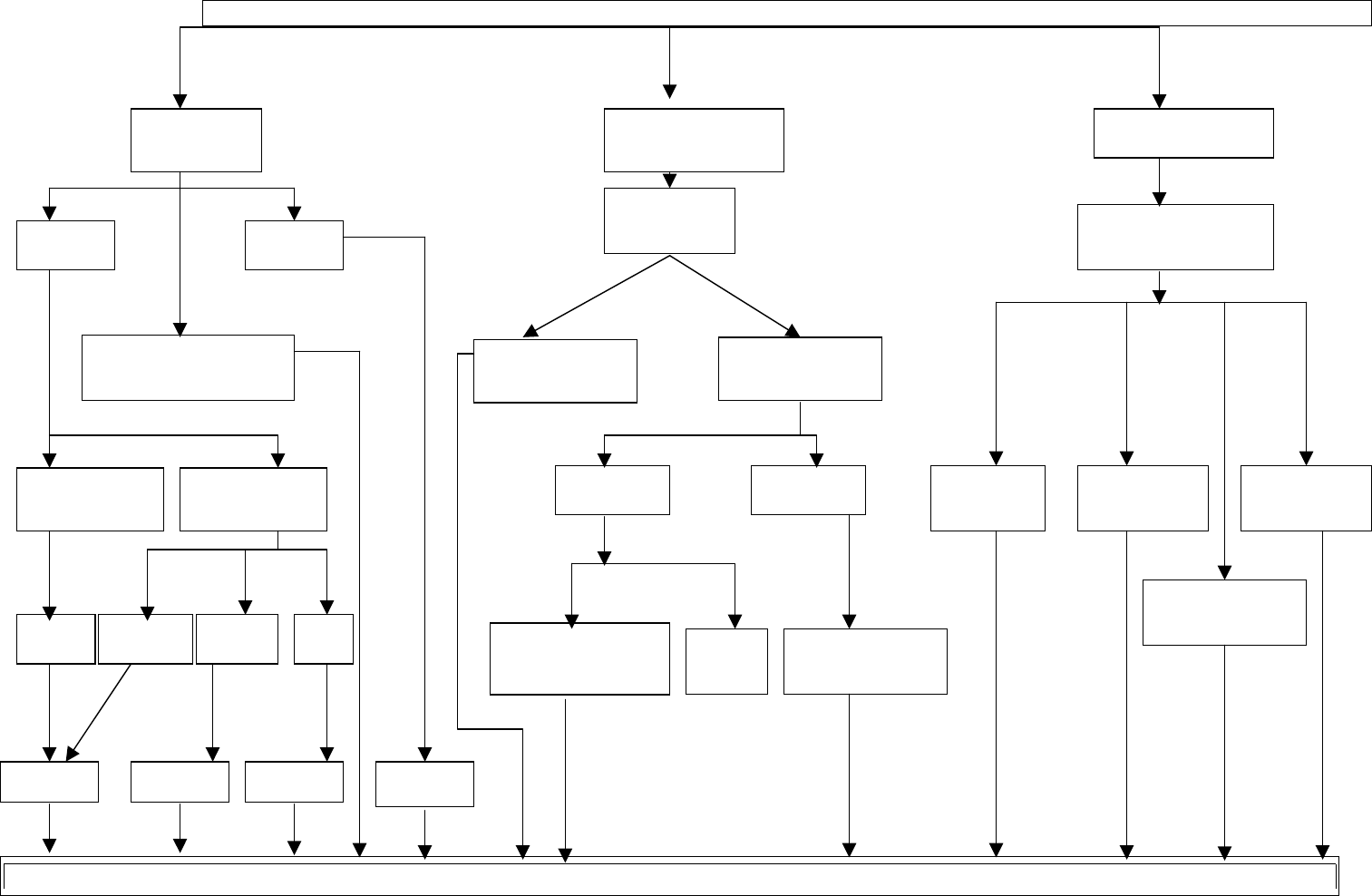

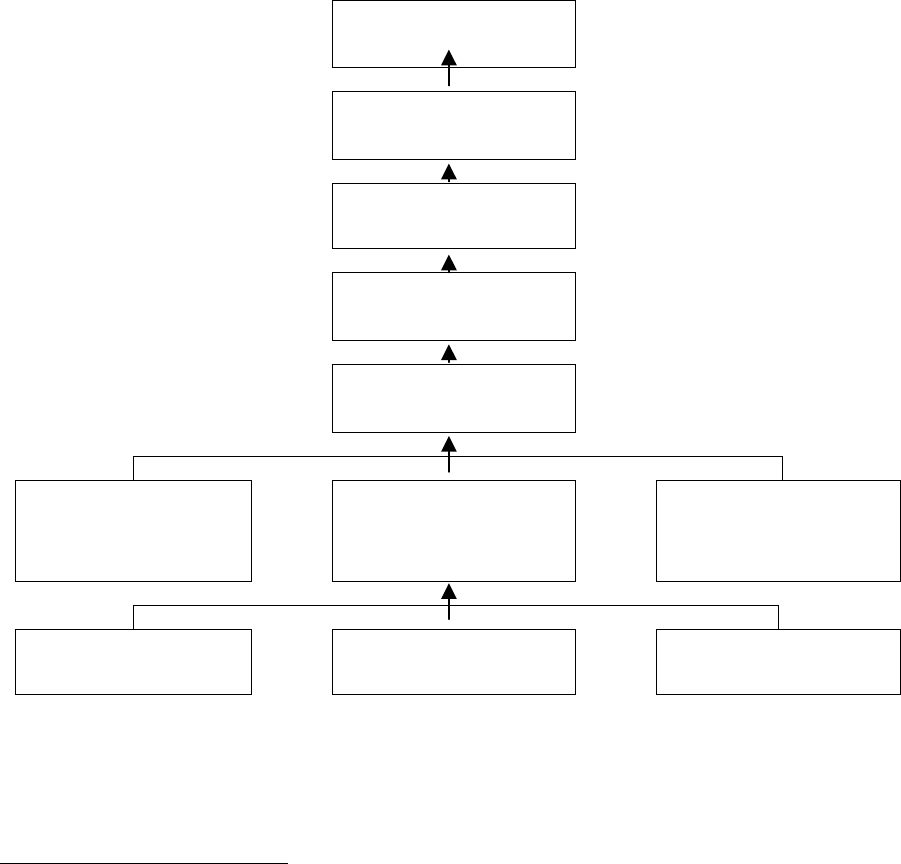

Chart 1 gives an overview of the micro finance actors in the Vietnamese Finance System.

4.1. The Formal Finance System

In 1999, as much as 5.9 million households had access to formal financial institutions, of which 2.7

million households were poor and low-income households.

23

4.1.1. The Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (VBARD)

24

The Vietnam Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (VBARD), before called The Vietnam Bank

for Agriculture (VBA), was created in 1988 out of a department of the State Bank of Vietnam (SBV). Its

focus lies on financing all types of enterprises in rural areas. The VBARD has become the largest

supplier of institutional micro finance to rural households: the share of rural households having access

to credits, managed by VBARD, increased rapidly from 9% in 1992 to about 30% in 1994.

25

Although the VBARD is by far the most important financial institution in the rural area, it is still

underdeveloped. Some major disadvantages are the following:

- Loan size: According to the bank's definition, loans below 5 million VND are considered "small"

and represent about 50%. In table 1 it is shown that loans of 1 million VND, which represents

already a large sum for the poor, represent only around 16 % of the total amount of loans

allocated by VBARD.

23

DFID and SBV, Micro finance in Vietnam: micro finance policy issues and “lessons learned” in Vietnam, p. 5.

24

DFID and SBV, Micro finance in Vietnam, p.36.

25

Wolz A., The transformation of Rural Finance Systems in Vietnam, p. 5.

21

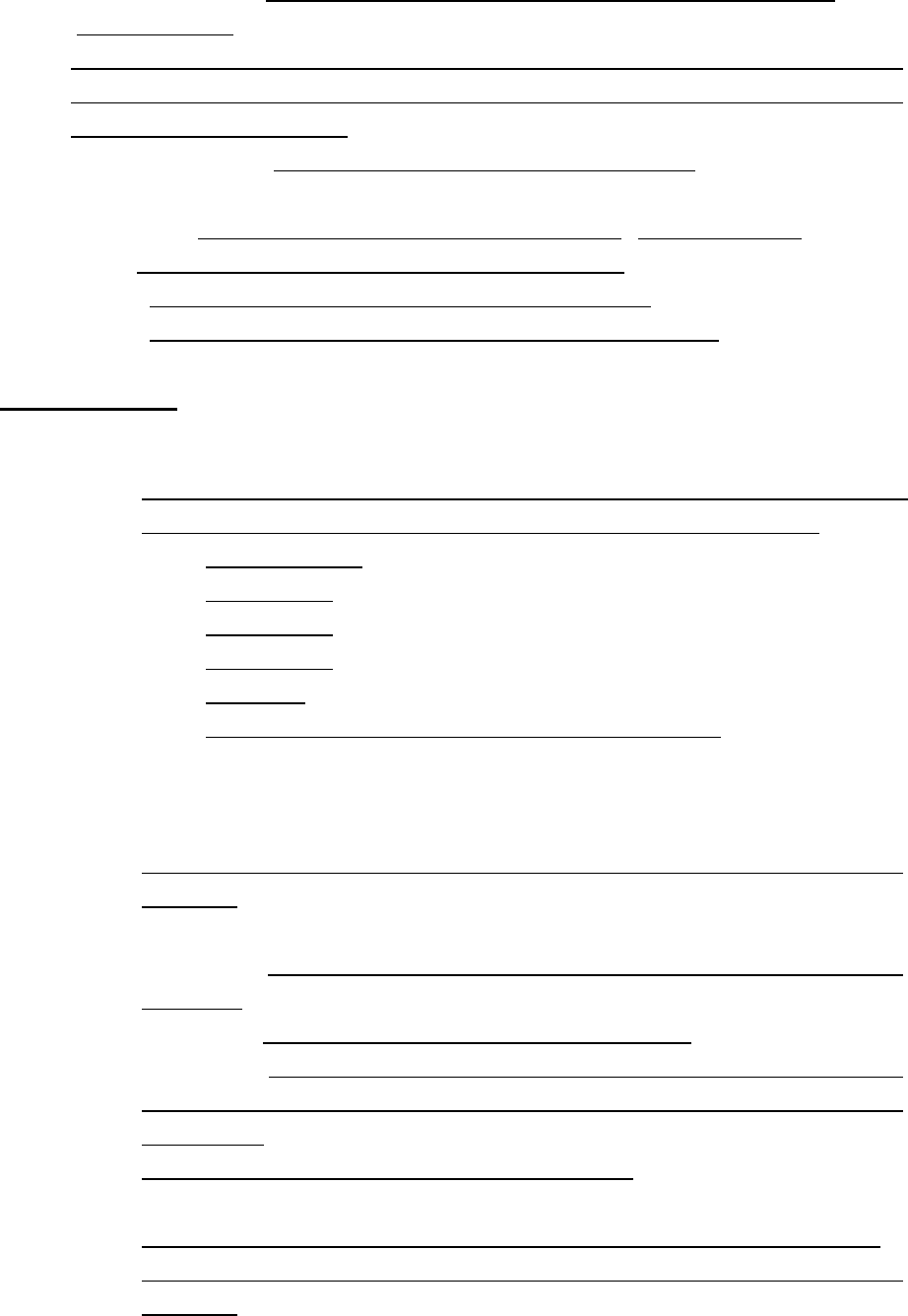

Chart 1: Overview of Micro Finance actors in the Vietnamese Finance System

Formal

sector

Semi-formal

sector

Informal sector

Banks

PCFs

Organized

entities

Non-organized

entities

Credit Cooperatives

Non-profit

banks

Commercial

banks

VBP

VBARD RJSCB IDB

Branch Branch Branch

Production

Coo

p

eratives

Money lenders

Similar

services

Relative,

Friends

Hui/Ho

(ROSCA)

Development

Programmes

Vietnam Foreign

Mass

Organizations

Technical

Agencies

Branch

Production Households, Business Units, Enterprises

PC

22

Loan Size (‘000,000 VND)

<0.5 0.5-1 1-3 3-5 >5 Total

share of customers % 5 11 29 33 22 100

share of total loans % 0.6 2.3 15.6 34 47.5 100

Table 1 : VBARD customer structures by loan size, 1998.

- Collateral: VBARD claims collateral when deciding about a credit application: residential

property, movable assets, goods and land right use are accepted as collateral. However only

about 30 % of households have "Red Certificates" of land use rights, so that the majority of

rural households are unable to respond to the demands of the VBARD linked to allocating a

loan.

26

- Banks prefer to provide credit to state-owned enterprises (SOEs). The credit amounts are much

larger, and therefore, handling costs relatively small. Risks are low because in case of default

the government is expected to come to their rescue.

- From the clients' point of view the procedures in getting a loan from VBARD are quite

complicated. It is costly (as well in time as in money) to get the necessary paper work done

when submitting the credit application. Often credit can only be asked for specific agricultural

investments but not for those activities, which are of priority to the borrower.

4.1.2. Vietnam Bank for the Poor (VBP)

The state-owned VBP was established in 1995. In the framework of the HEPR, it was the intention that

the approaches of VBARD and VBP complemented each other in their contribution to hunger

eradication and poverty alleviation in Vietnam.

The VBP is institutionally merged with the VBARD and staffed by personnel from VBARD. It officially

started operating in 1996 to provide subsidized credit to poor households. Its aim is to reduce poverty

by providing loans with low interest rates to the rural poor, who do not qualify for individual loans

because of limited ownership of potential collateral. The VBARD and VBP branch network is present at

district level and to a limited extent at commune level, through visits of loan officers to communes on a

weekly basis. This limits their outreach to the poorer, remote, rural communes. Up to 1999, over 2.3

million poor households obtained loans for a total amount of about 276 million US$.

27

The VBP closely cooperates with local organizations. Local People's Committees usually help VBP

identify who are the poor. Social mass organizations at villages like the Women Union and the Farmer

Association help the bank monitor the loans. The borrowers don’t need a collateral, but in reality it is the

social mass organization, which provides a Guarantee Fund to the bank. If the borrowers do not repay

the loan, the bank will take a part of the Guarantee Fund. To ensure repayment, the mass

organizations organise the borrowers in joint-liability groups.

26

DFID and SBV, Micro finance in Vietnam: institutional and legal structure of micro finance in Vietnam, p.12.

27

DFID and SBV, Micro finance in Vietnam, p. 8.

23

4.1.3. People's Credit Funds (PCFs)

After the collapse of the rural credit cooperatives, SBV has been entrusted to reorganize the system of

rural credit cooperatives. The result was the development of a network of People's Credit Funds (PCF).

PCFs have been created in nearly all provinces of Vietnam (limited coverage in the Northern

Mountainous areas). One of the most important objectives was to restore public confidence in the

formal rural finance system. For psychological reasons, the term ‘cooperative’ has been deliberately

excluded from the name of this newly established finance institution. The PCF-system has been set up

as a member-owned organization, which aims at mobilizing savings from its members. It has to be

managed according to the economic principle of cost covering; no ‘easy money’ will be available

(although they did had the back-up of SVB for several years).

PCFs are shareholding banks and do not focus on the poor. 15 potential founding members are

required to set up a PCF. These persons have to be better off since for setting up a PCF a base capital

amounting to 50 million VND is required and each founding member has to buy minimum shares

amounting to 3.3 million VND. Once the PCF is registered it aims at recruiting more members. Those

who want to become member have to buy a share of 50,000 VND, an amount too big for the poor.

28

The PCF-network has been established predominantly in those areas which are economically better off

and better developed in infrastructure. Therefore the PCF-system only has a limited role to play with

respect to reducing rural poverty. Its major accomplishment will be to provide a viable rural finance

system to farm and small entrepreneurial households to stimulate economic development, which

indirectly contributes to poverty eradication.

PCFs are situated close to their clients, have relatively fast loan-approval processes and have the

potential to provide competition in the rural financial sector.

4.1.4. Main problems affecting the Formal Finance System

The two Government-owned banks (VBARD and VBP) are the major sources of formal credit for rural

households. Rather than functioning as self-sustainable independent banks, they are mainly used as a

channel to provide formal credit to farm and poor households in the rural areas. Although the number

of households obtaining credit has increased sharply since the establishment of VBARD, VBP and

PCFs, there are still a large number of poor households unable to get access to formal institutional

micro finance.

Despite general improvements, the policy environment for micro finance in Vietnam remains

unfavourable for sustainable growth in micro finance operations.

24

4.1.4.1. Interest rate structure

Aiming at providing the poor with a preferential treatment, the Government has tried to make cheap

credit available in order to assist the poor to develop their own production and business operations.

The SBV determines the interest rate for credit. This means that banks are not able to set interest rates

that will cover the costs of funds, operating costs and risks. Since August 2000, the mechanism of base

interest rates has been applied for all formal financial institutions, in stead of a ceiling interest rate. This

liberalization of the interest rate gives financial institutions a little more freedom in determining the rates

on lending and saving. However, the base interest rates are not flexibly adjusted to market prices, so

the effects of base interest rate are almost the same as that of the ceiling interest rates mechanism.

With an interest rate so low and generally high operating costs, it is impossible for a bank to become

self-sustainable. Because operating costs of bigger loans are rather low compared to loans of small

amounts, the provision of financial services to small rural borrowers is no longer a commercially viable

option for VBARD.

29

It can be argued that the policy of determining interest rates, which is supposed to

stimulate economic and agricultural growth, is actually limiting the access to credit and increasing credit

costs for farmers and rural entrepreneurs. For the rural financial institutions like VBARD, VBP and PCF

the determined interest rates is a constraint for a sustainable expansion of their services.

Interest rate of loans has been held at 1% per month for VBARD and at 0.7% per month for VBP, which

is lower than the interest rate charged by non-state owned commercial banks. Due to this low interest

rate, it is difficult to raise funds. Therefore, they have to rely on borrowed fund from the Government.

Although the VBP has become the major source of formal loans to the poor households, at current

rates of lending and institutional structure, the bank cannot afford financial nor institutional

sustainability. Basically the VBP has been a channel to provide subsidized credit to the poor.

It is generally recognised that the mechanism of subsidised credit undermines the sustainable

development of micro finance. Low interest rate leads to demand exceeding the loan supply.

Consequently not everybody who wants a loan can get one. Obviously banks prefer to select the least

risky borrowers (such as those with good collateral) and prefer to give larger loans, which implies lower

administration costs. However there is also neither guarantee nor a protection against corruption.

In the long-term the Government intents to gradually improve the ability of the poor, especially poor

women, to access the formal credit system by simplifying the procedures rather than applying

preferential credit policies.

30

28

PCFs plan to include poorer areas after they have established a strong and sustainable credit union network.

29

BADC and VWU, Proceedings of the Workshop, June 1998, p. 45-47.

30

Comprehensive Poverty Reduction and Growth Strategy, January 2002.

25

4.1.4.2. Saving Mobilization

Formal micro finance institutions have no serious attitude and effort to mobilize small savings. In the

government banks, savings mobilization instruments have been poorly designed. It is impossible to

offer attractive interest rates to savers if interest rates on lending are limited. Taking the psychological

effects of the collapse of the cooperatives in mind, the low interest rates on lending, also make the

rates on savings rather low, and in the viewpoint of many people, not worth the risk of depositing their

money.

From the point of view of the financial institution, interest rate margins do not create incentives to

expand savings services to the poor and low-income households. For some financial institutions, small

saving deposits are not accepted. For example, the minimum deposit accepted by VBARD branches is

50,000 VND, and sometimes even 100,000 VND. As a result, rural micro finance institutions must rely

on savings from urban areas rather than small savings in rural areas. VBARD deposits are

overwhelmingly urban with only a very small proportion coming from rural households. VBP deposits

make up only 8 %of its total funds.

31

4.2. The Informal Finance System

Although the knowledge about informal finance systems in Vietnam is weak and primarily based on

anecdotal evidence, informal sector lending seems to remain of great importance in rural Vietnam. Data

collected by the VLSS of 1997-98 revealed that 51 percent of credit to farm households were being

provided through the informal channel (table 2).

32

Compared to the results of the 1992-93 VLSS

(where 73% of loan funds in rural areas were provided by private moneylenders and individuals), a

significant decrease of the share of credit provided by moneylenders can be noticed: 33% in 1992-93

and 10% in 1997-98.

number of

loans(%)

average loan size

('000 VND)

Informal financial sector 51 1,752.10

money lenders 9.8 2,141.30

Relatives 24.2 1,860.90

ROSCA and other individuals 16.8 1,365.70

formal & semi-formal financial sector 49 3,208.50

Table 2: Number of loans and average loan size by sources

Despite this decline, the results of the VLSS 1997-98 reflect that private individuals remain the most

important source of credit for rural poor, in most cases family members, relatives, friends and

neighbours. Reasons why there is such a big informal market of credit :

31

DFID and SBV, Micro finance in Vietnam: institutional and legal structure of micro finance in Vietnam,. 12.

32

DFID and SBV, Micro finance in Vietnam: institutional and legal structure of micro finance in Vietnam, p. 6.

26

- As a result of the collapse of the credit cooperatives there is a significant lack of trust of the

people in the formal banking system;

- The procedures for access to formal credit are too complicated (too long administrative

procedures, collateral,…)

Three major informal financial sources of credit in Vietnam can be distinguished.

33

4.2.1. Relatives / friends / neighbours

Relatives, friends and neighbours are the first sources when seeking for credit. They lend to others at

negotiated rates depending on social relationships and reputation. Taking advantage of personal

information, relatives and friends in general provide loans without collateral or any other written loan

contract. Interest rates are recorded low (neighbours) and in many cases (relatives and close friends)

are free. The purpose of the loans is generally for emergency consumption such as illness, funeral and

weddings and for the building or repairing of houses. Rarely those loans are used for buying input for

production.

4.2.2. Ho/Hui

34

Rotating savings and credit associations (ROSCAs) have a very long tradition in Vietnam. Although

they exist for many generations already, they have never been recognized officially. Usually these

groups are referred to as Ho in the North and Hui in the South. They are promoting periodic saving

contributions, which in turn are rotated as a fund among a limited group of persons who trust each

other. Members of these associations come mainly from the same hamlet, and are even organized ‘on

the spot’ between colleagues and friends. The savings and credit can be made either in cash or in

kind. In general, membership averages 10-15 persons. Decision on interest rates, membership and

loan amounts are made either jointly by all members, by a bidding process or made solely by the

organiser. The life cycle of a savings and credit association ends when every participant has obtained

once the total fund collected at each turn. Most of the Ho/Hui are set up to bridge short-term needs

(sometimes for special purposes such as weddings, funerals or the lunar new year), but they can also

be set- up to finance long-term investments.

4.2.3. Moneylenders

Private moneylenders are widespread and seem to be important sources of loan for households. It are

usually the rich households with surplus of money and goods in rural areas, who lend money for long-

term periods against sometimes very high interest rates. Moneylenders are reported to charge up to an

average of 10% per month, which is extremely higher than the rate charged by formal financial

institutions. In HCMC the reported rates of interest are even much higher 20% to 30%, even sometimes

33

Tran Tho Dat, Analysis of the Informal Credit Sector in Vietnam, p. 1-4.

34

Wolz A., The Transformation of Rural Finance Systems in Vietnam, p.16-17.

27

as high as 70% per month.

35

Sometimes the moneylenders are traders who give advances in cash or

kind on the basis of the promise to receive or buy the products at harvest time. This last type of lending

has been developed during the last years and it can be assumed that they will become a more

important source of rural credit in the years to come.

Why do people borrow from moneylenders when they charge such a big interest? In many cases, the

timely availability and quality of service are more important to farmers and rural entrepreneurs than the

level of interest rate. Generally moneylenders don’t ask for a collateral and have no complicated

administrative regulations to follow before getting the loan.

4.3. The Semi-formal Finance System

The semi formal finance system consists of various structures of decentralised financing which offer

micro finance services and try to reach those populations excluded from the official banking circuits. A

survey in the year 2000, organised by DFID, identified 76 schemes outside the formal sector

representing about 35% of total amount of the loans.

36

However, in this survey important schemes

conducted by the Women’s Union are missing, such as for example the TYM scheme and the VBCP

project.

Mass organizations play a crucial role in the implementation of donor supported micro finance

schemes. Mass organizations have their origins in the Communist Party of Vietnam and the struggle for

national liberation. They form the link between the Communist Party and major socio-economic groups

such as women, farmers, peasants, youth, war veterans etc. These organizations are usually

represented at four administrative levels: national, provincial, district and commune. This structure

enables the mass organizations to have a direct contact with the grassroots and to establish a

connection with the national level.

The Vietnam Women's Union (VWU) was created on 20 October 1930. As a social organization, it

represents women of all strata but predominantly rural women aged between 30 and 50. The VWU is

the most important mass organization in Vietnam and works in tandem with the Government, the

administration and the Communist Party structures at all levels (national, provincial, district, commune).

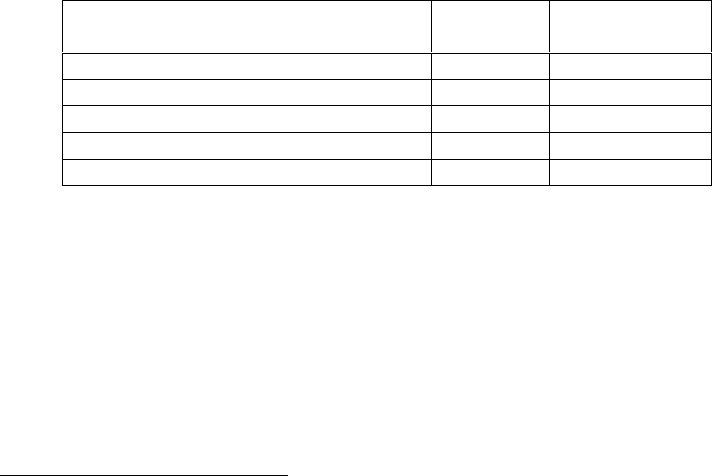

Chart 1 shows the organization and activities of the Vietnam Women’s Union.

Since the early 1990s several mass organizations encouraged micro finance schemes and the

formation of groups. A number of them are active in micro finance, but the Vietnam Women's Union is

the most active nation-wide. A lot of development programmes, financed by national or international

funds, cooperate in its implementation with the VWU.

35

Save the Children (UK), WB and DFID(UK), Poverty in Ho Chi Minh City. A Participatory Assessment, p. 54.

36

DFID and SBV, Micro finance in Vietnam: a survey of schemes and issues, April 2001.

28

Under the Credit Law of Vietnam (Law N° 02/1997/QH10, 01/10/1998), only recognized institutions can

deliver services of credit or savings. This law is not strictly applied and small credit or savings projects

are tolerated because they bring important amounts of capital to the grass-root levels. Credit and

savings organizations are however controlled and sometimes restricted at local or national levels. But

savers and borrowers need legal protection because they cannot control the accounts and

management systems of the funds. If something goes wrong the savers can lose their deposits. As a

non-profit Vietnamese organization with social goals, correctly controlled and managed, the VWU

obtained official support to continue its micro finance activities.

37

The sector is highly subsidised by donors who see this as a means for providing more efficient aid to

poor families in rural areas and thus combat poverty. Poverty reduction through credit schemes has

become the central concern in the partnership of many international donors.

38

They are operating in

various areas throughout the country with different credit and saving schemes. The international

organizations provide credit for poor in various models.

The general feeling is that these credit schemes work well, in particular because repayment rates are

generally high. However the expansion of the schemes is less rapid than could have been expected.

This can be partly explained by the rapid growth of the formal sector, but also by the lack of legal

framework and the internal policy.

37

Official letter from the Government Office to the VWU and the SBV, dated January 17

th

2000, in: TFF VBCP.

38

BADC and VWU, Proceedings of the Workshop, June 1998, p. 18.

29

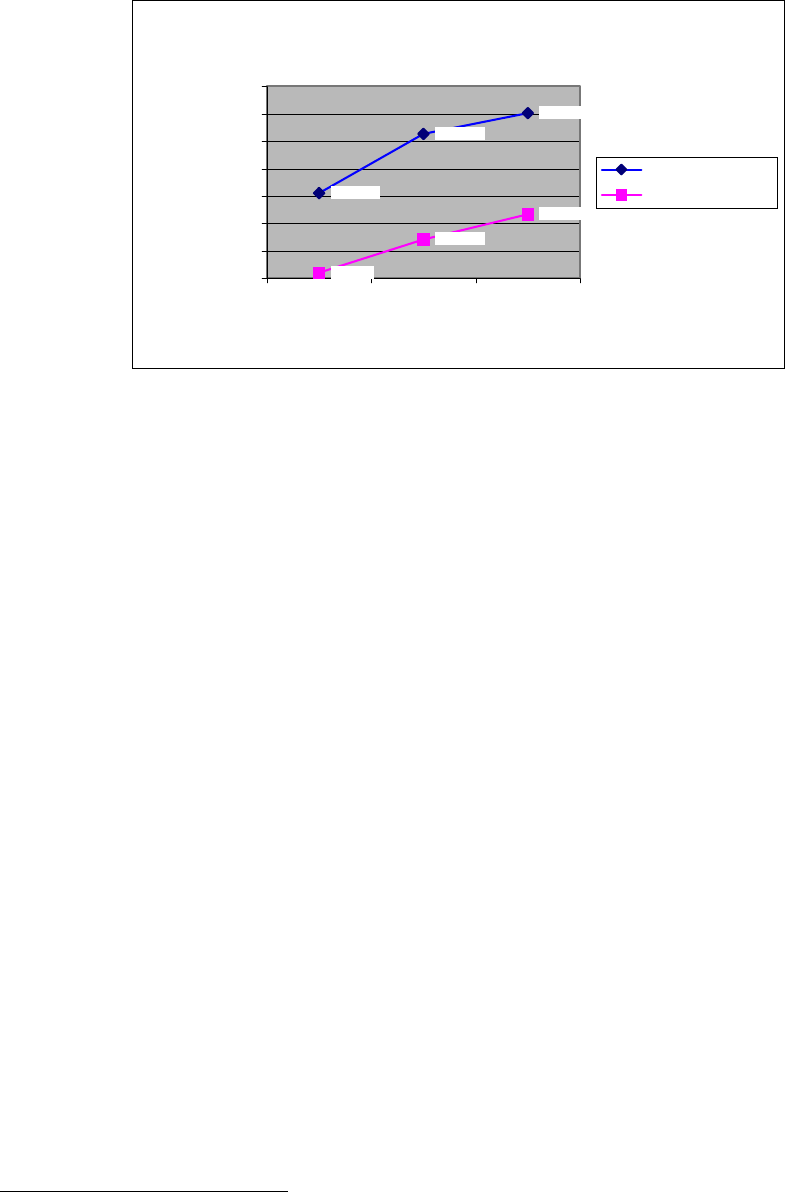

Chart 2: Organization chart of the Vietnam Women’s Union

39

39

VBCP, Technical and Financial File.

National

Congress

Central Executive Committee

Presidium

Central

Level

Departments

General

Administration

Women’s Studies

Development Project

Management

Personnel

Department

Women’s Training

School

Peace Tour Company

TYM Fund

International Cooperation

Communication and

Education

Ethics and

Religions

Family and

Welfare

Women’s Weekly

Newspaper

Women’s

Publishing

Women’s Museum

Province Women’s Union

District Women’s Union

Commune Women’s

Union

30

Case study I: VBCP project

Strengthening of the institutional capacity of the Vietnamese Women’s Union to manage savings and

credit programmes for rural poor women

1.1. Background

The Vietnamese – Belgian Credit Project “Strengthening of the institutional capacity of the Vietnamese

Women’s Union to manage savings and credit programs for rural poor women” is a bilateral project

following an agreement by the Government of Vietnam and the Government of Belgium, signed in

1996. The budget for the entire project amounted to 54 million Belgian francs (1,338,625 €) of which 16

million Belgian francs to be used for a revolving fund. The first phase started in December 1997 for a

period of 3 years and was immediately followed by a second phase of 4 years.

40

The project is

executed by the Vietnam Women’s Union (VWU) and the Belgian Technical Cooperation (BTC).

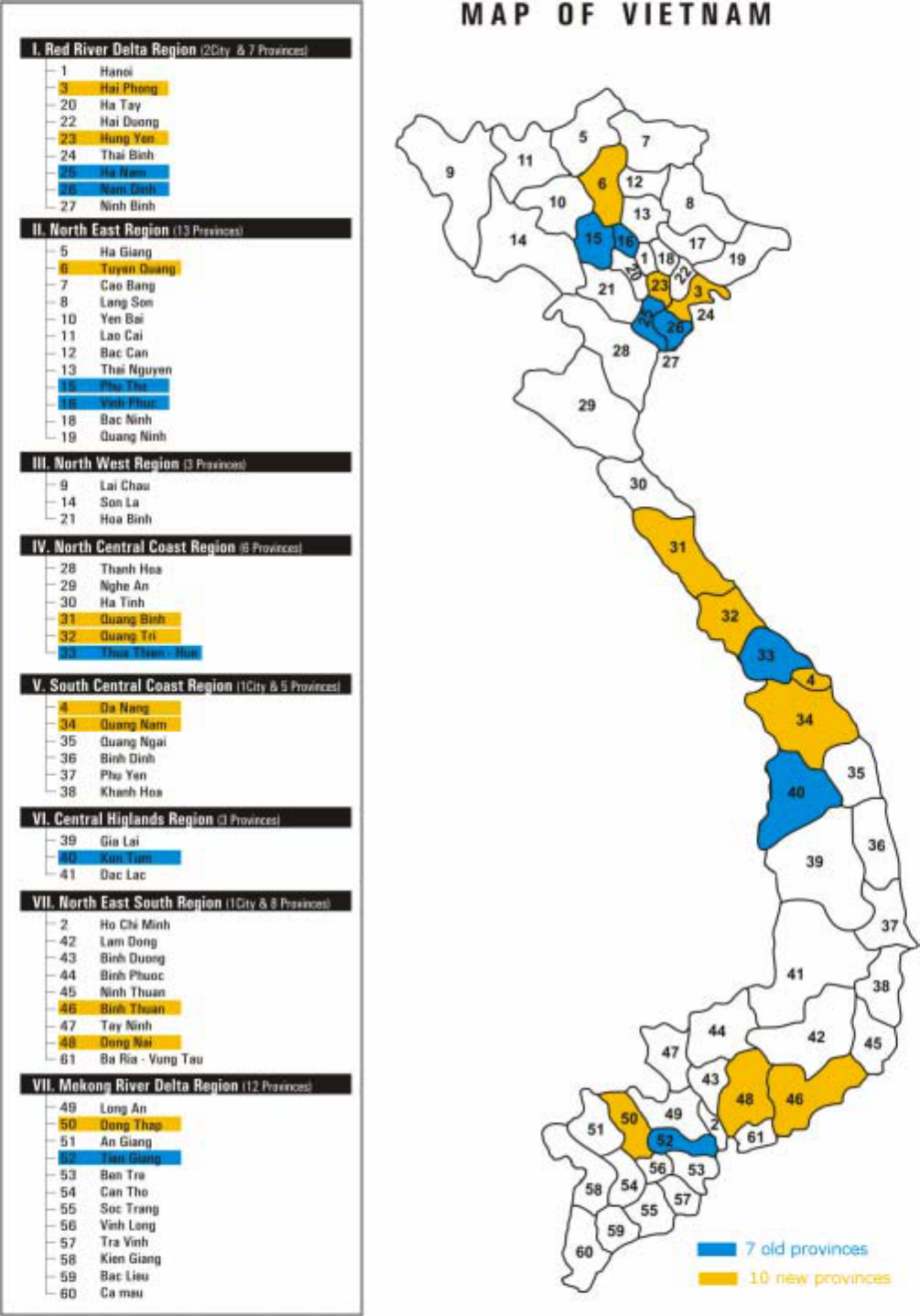

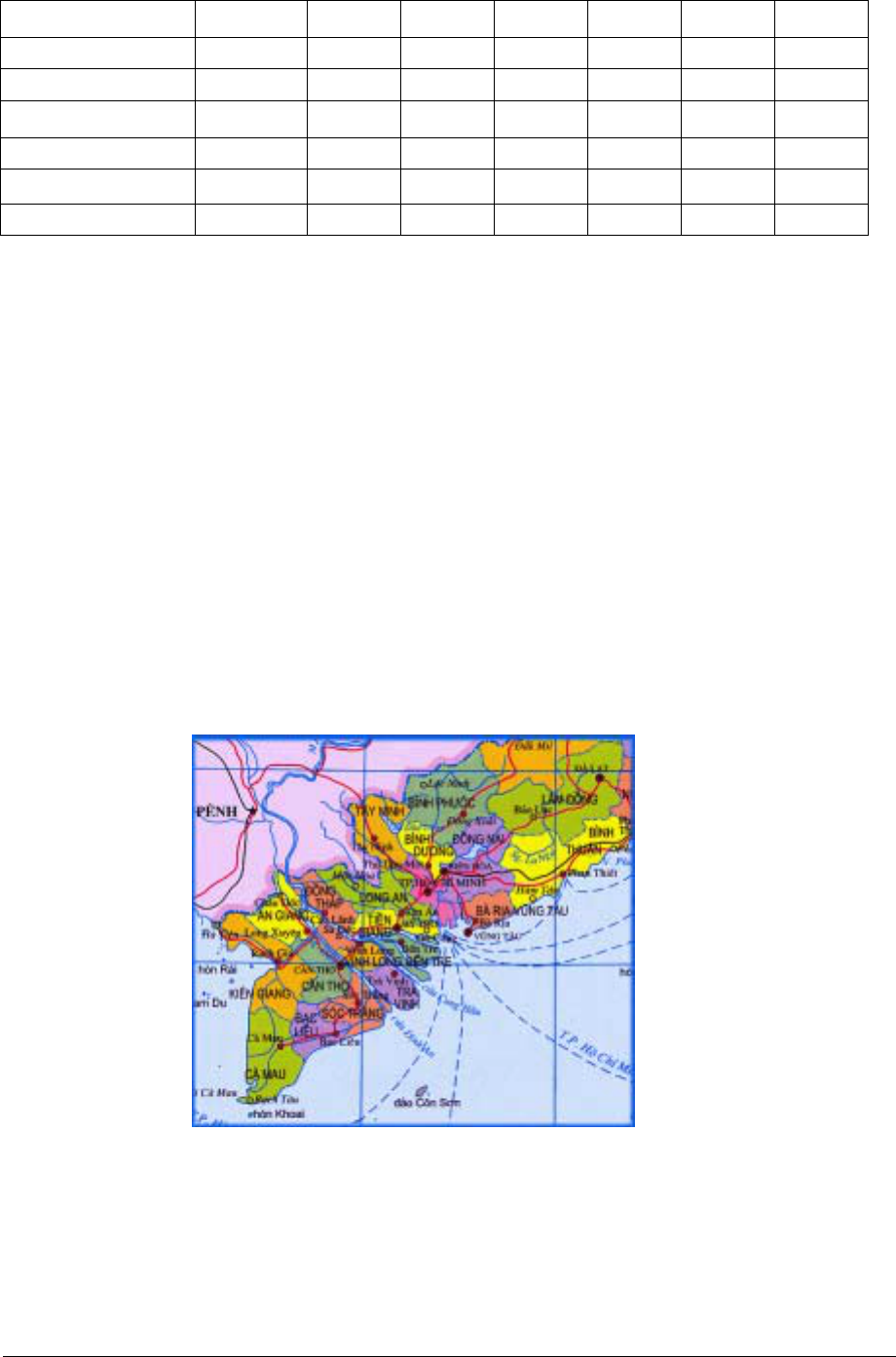

1.1.1. Project area

During the first phase, the project has been implemented in 57 districts of 7 provinces throughout over

Vietnam (see map 2): 4 in northern Vietnam, 2 in central Vietnam and 1 in southern Vietnam. In each

district, 1 commune has been selected. Out of the 7 provinces, 1 province (Nam Dinh) is classified in

the High HDI rank, 5 provinces are classified in the Medium HDI rank and 1 (Kon Tum) in the Low HDI

rank. During the second phase of the project, new communes in the initial 7 provinces will be involved

as well as communes selected in 10 other provinces.

1.1.2. Objectives of the project

The general objective is to improve the living standard of poor rural women and their families.

The specific objective of the project is to consolidate and strengthen the institutional capacity of the

VWU in managing micro finance programs.

2. Micro finance scheme

2.1. Methodology

The credit model is based on the solidarity group methodology.

Groups are composed of 10 women in a similar socio-economic position, who know each other and

who are willing to support each other in borrowing loans and following the project regulations. Each

group selects a group leader who gets a training to manage the group. The position of group leaders

rotates on a yearly basis.

40

The current report will only tackle the results of the first period.

31

32

A centre is composed of three groups with 10 members each. Each centre has a monthly centre

meeting chaired by an elected centre chief. The meeting schedule is fixed and includes disbursement

of loans, collection of loan repayments, interest and savings. During these meetings information is

shared, on topics that are not linked to micro finance (e.g. health, woman emancipation, family

planning, etc.).

The procedures to obtain a non-collateral loan are simple. The project provided extensive training to the

staff of the VWU at all levels as well as to group leaders and potential borrowers. Two thirds of the total

funds were used for capacity building of staff of the VWU at all levels and of the clients, and for the

purchase of equipment. Borrowers, who have proven to be reliable during a first loan, can apply for

supplementary short-term loans to scale up their production.

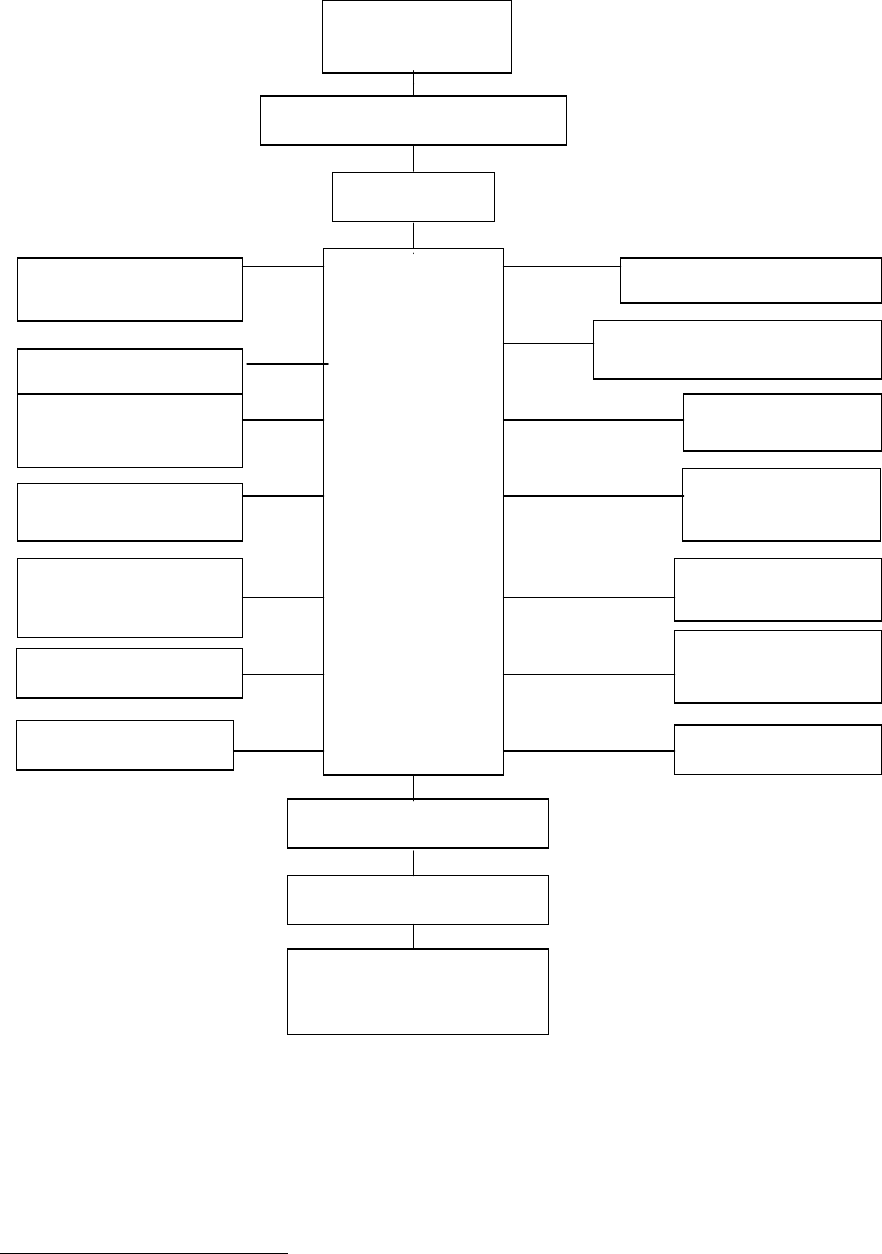

2.2. Management of the micro finance scheme

The management of the project is conducted at 4 levels of the VWU organisation (central, provincial,

district and commune), involving 334 staff members. Chart 3 shows the structure of the management of

the project.

41

Steering Committee

Central PPMU

Provincial PPMU

(with Micro Banker computer)

District PPMU

Commune PPMU

Center (3 Groups)

- Center chief

-

Secretary

Center (3 Groups)

- Center chief

-

Secretary

Center (3 Groups)

- Center chief

-

Secretary

Group (10 borrowers)

-

Group leader

Group (10 borrowers)

-

Group leader

Group (10 borrowers)

-

Group leader

Chart 3: organizational structure of the project

41

VBCP, Technical and Financial File, annex 4.

33

2.3. Credit and savings scheme

2.3.1. Target group

The target group of the project are poor women in rural areas, who have the capacity to develop

income-generating activities

To become a member the following conditions should be fulfilled:

• no loans from other credit projects or formal financial institutions have been obtained

• members are working poor rural women, between 18-55 years and in good physical and mental

condition

• members have a resident certificate and live permanently in the area

• members are willing to follow all group regulations

• there are no opium addicts or gamblers among the members of the family

2.3.2. Loan use

The loans are used for production investment in small business projects to increase the households’

economy. Prior to receiving a loan, the new borrowers have to submit a business plan together with

their loan application. The vast majority of the portfolio is used for agriculture and animal husbandry

(pig, ducks and chicken raising). The project helps to identify alternative income-generating

opportunities other than farm business activities (for example handicraft, cook some food to sell on the

market, etc).

42

2.3.3. Loan terms and conditions

The project has two kinds of loans (general loan and seasonal loan) and many loan cycles, which

makes it possible for poor women to borrow loans from small to bigger amounts to invest in

production.

43

General loan:

• Borrowers may choose to borrow either 500,000 VND or 1,000,000 VND

44

• The loan term is 1 year

• The principal and interest repayments are done monthly in equal instalments, from the first

month onwards

• The interest rate on loans is 1% per month on the outstanding balance (= declining rate)

Seasonal loan

• The loan size can be decided by the borrower, with a minimum of 300,000 VND and a

maximum of 500,000 VND

• The loan term is 3 to 6 months

• The principal and interest repayments are done monthly, from the first month onwards

• The interest rate on loans is 1,2% per month on the outstanding balance (= declining rate)

42

VBCP, Activity Report, Augustus 1999 - February 2000, Annex 1, p. 9-11.

43

VBCP, Final Report, Hanoi 2001, annex 1, p. 2.

44

Will be increased to 1,000,000 and 1,500,000 VND for the second phase.

34

The VBCP project has a special Member’s Mutual fund, which is used in case a borrower dies or in

case of natural disasters. Each member has to contribute 500 VND every month, out of which 300 VND

is for the Natural Disaster Fund and 200 VND for the Death Fund.

2.3.4. Savings

The project works with an initial compulsory saving of 50,000 VND that is withdrawn from the loan.

Besides this initial saving, monthly compulsory savings of 5,000 VND per borrower are paid together

with the principal repayments. People can put as much voluntary savings as they want.

Borrowers can withdraw their savings at the end of the loan cycle, for which an interest rate of 0.5% per

month is paid.

2.4. Financial management and monitoring

The financial management of the scheme has been computerized with the Micro Banker system, i.e. a

banking software developed by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). The system was entirely

translated into Vietnamese by the project and adapted to the chosen credit model. Computers were

installed at the provincial office of the VWU and connected to the central level of the project. In the

head office the data of the 7 provinces are consolidated. Crystal software programme for Management

Inforamtion System (MIS) has been installed, using data provided by the Micro Banker system and

allowing the generation of monthly comprehensive financial reports including ratios so that appropriate

measures can be taken immediately. For the follow-up of Micro Banker, two international consultants

are invited on an ad hoc basis.

2.5. Results

The first loans were allocated in March 1999 in one test commune, nearly 1.5 year after the start of the

project. The credit model was adapted and finalized in August 1999 and very rapidly the scheme was

applied in all 57 communes, which all received a starting fund of about 7,600 US$. Table 3 shows the

results up to the 31

st

of November 2001.

45

31/11/2001

Initial capital 6,177,248,282 VND

Total loans amount disbursed 39,560,100,000 VND

Outstanding balance 13,314,500,000 VND

Accumulated savings balance 3,496,400,000 VND

Accumulated number of borrowers 39,500

Active borrowers 11,921

Repayment rate 99,7%

Table 3: Overview of the results of the credit model of the VBCP up to 31/11/2001

45

VBCP, Final Report, Hanoi 2001, p. 30.

35

The Micro Banker system allows the project staff to manage a big amount of customers’ information

and loan/savings accounts and to produce balance sheets, profit & loss statement, and trial balances at

any time and this both consolidated and by branch (1 branch per province). Micro Banker provides

numerous safety mechanisms such as a system of compulsory daily back-ups.

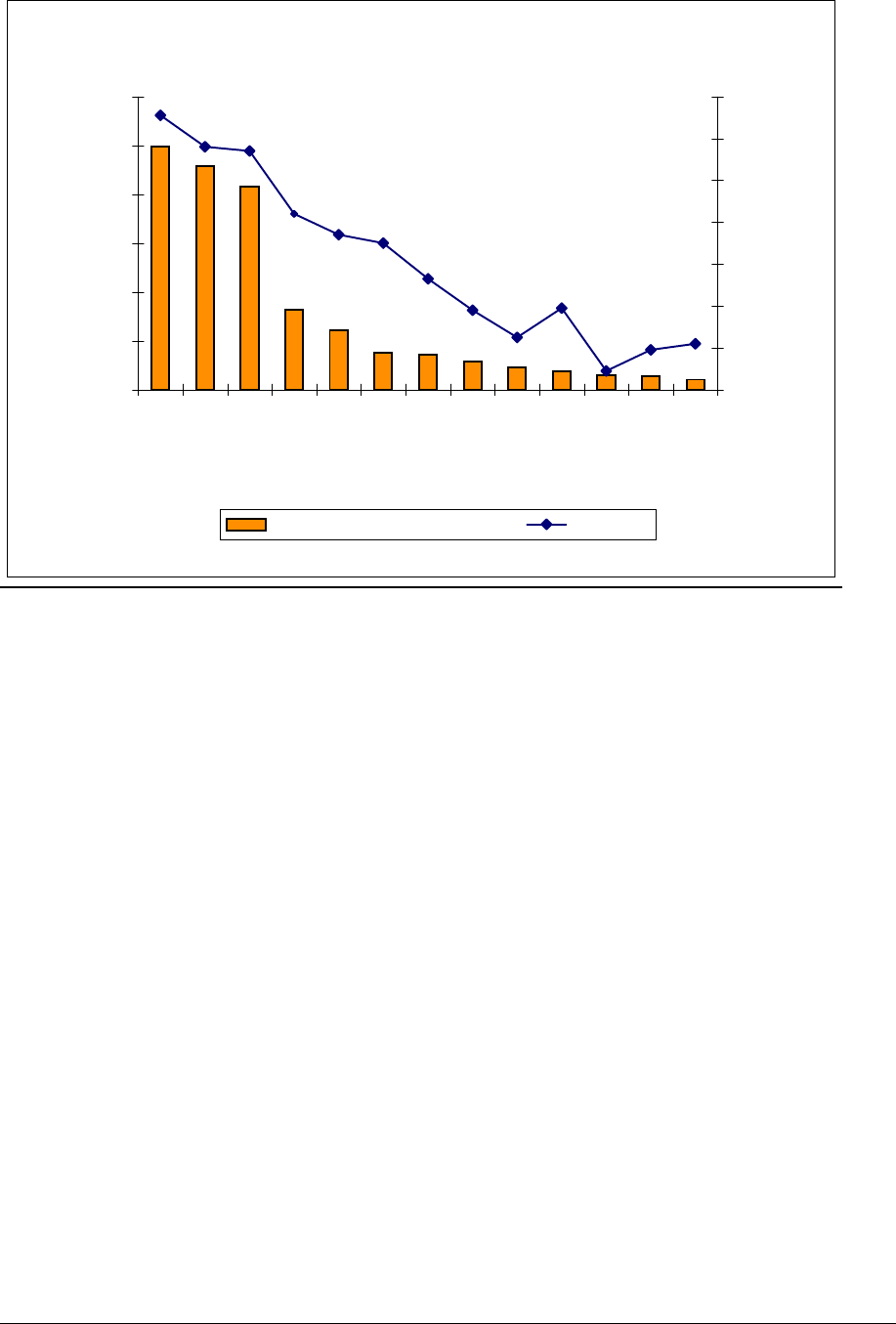

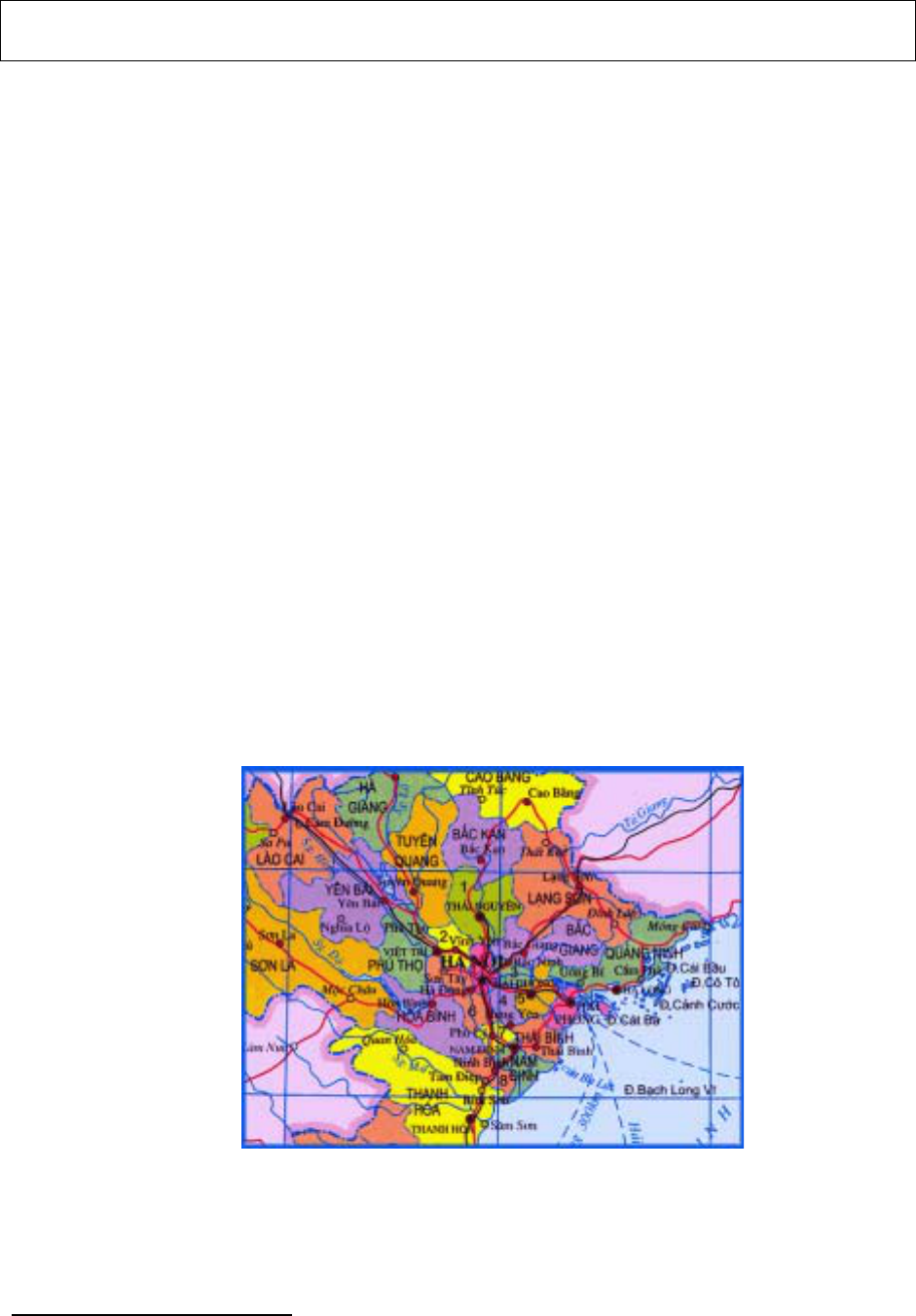

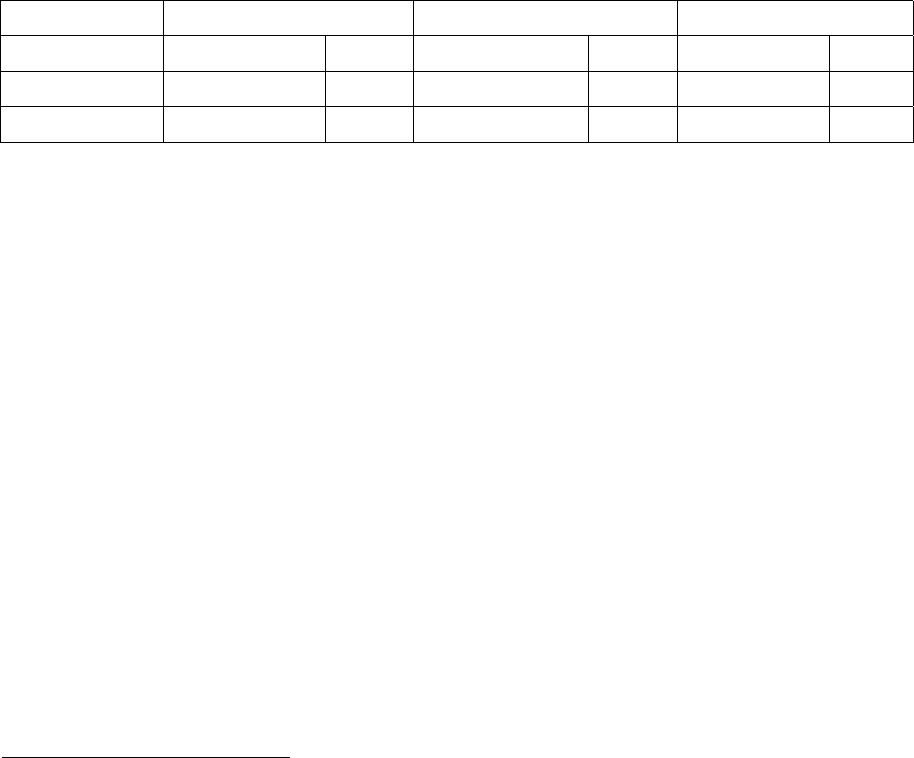

Outstanding loans - Saving balance

310.667

526.334

602.736

19.786

140.849

233.096

-

100.000

200.000

300.000

400.000

500.000

600.000

700.000

1999 2000 2001

Year

Value (in USD)

Outstanding loans

Saving balance

Figure 3: VBCP project: outstanding loans – Savings balance

The systematic MIS reports enable the central project staff to analyse and evaluate the status of loan

portfolio, outreach of the credit/savings, financial status, operating efficiency and possibility of financial

sustainability for timely decisions or adjustments. MIS also helps the head office to evaluate the

accuracy of data entries done by the provincial Micro Banker users and discovers incorrect data-entry

to resolve on time.

46

Training is a key factor and important task of the project to ensure good quality of the project

implementation. Training of project staff is mainly focused on credit/savings management, on computer

skills and the use of the Micro Banker system, on basic accounting and the management information

system. Training of borrowers focused on the project’s objectives, operating system, credit/savings

scheme, borrowers’ responsibilities, loan procedure and simple production/business planning.

47

46

Project document: Project overview, p.3.

47

VBCP, Final Report, Hanoi 2001, p. 28.

36

Case study II: FAO project

Participatory Watershed Management in the Hoanh Bo District, Quang Ninh Province

2.1. Background