Page 1 of 11

© Health Technology. All rights reserved.

Health Technol 2021;5:10 | http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/ht-20-29

Introduction

Infants grow significantly in the first year of their lives

requiring parents to keep up with their constantly changing

needs (1). The literature on parents’ use of online resources

suggests mobile applications or “apps” are commonly used

by parents to resolve their everyday parenting concerns

(2-4). Parents use apps for things like retrieving information

on parenting topics, getting support from friends, family,

and other parents, and tracking their babies’ growth on a

daily basis (5-7).

The proliferation of low-quality and irrelevant apps

creates barriers for parents in effectively accessing parenting

material. Taki and colleagues (8) performed a systematic

analysis of infant feeding apps and reported 91% were of

poor quality due to issues with user interface design (e.g.,

navigation) and content (e.g., readability). Many evidence-

based apps are invisible to users because they are lumped

in with poor quality apps. By 2018, 84,000 publishers had

Original Article

Co-designing an e-resource to support’ search for mobile apps

Anila Virani^, Linda Duffett-Leger, Nicole Letourneau

Faculty of Nursing, University of Calgary, Calgary, Canada

Contributions: (I) Conception and design: All authors; (II) Administrative support: All authors; (III) Provision of study materials or patients: All

authors; (IV) Collection and assembly of data: A Virani; (V) Data analysis and interpretation: A Virani, L Duffett-Leger; (VI) Manuscript writing: All

authors; (VII) Final approval of manuscript: All authors.

Correspondence to: Anila Virani, RN, BScN, MN, PhD. Faculty of Nursing, University of Calgary, 2500 University Drive NW, Calgary, AB T2N 1N4,

Calgary, Canada. Email: avirani@ucalgary.ca.

Background:

Contemporary parents use mobile applications or “apps” to resolve their day-to-day parenting

concerns. However, research suggests an abundance of low-quality apps makes the app searching process

arduous for parents, therefore, there is a need to develop a resource that supports parents’ search for apps.

Methods:

The study aimed at engaging parents in co-developing a parenting app directory and co-

designing Webpages to feature the directory. Four focus group discussions were conducted with 18 rst-

time Canadian parents to develop the parenting app directory. Participatory design was used to co-create

Webpage prototypes (landing or main Webpage and the app description page) with 3 rst-time Canadian

parents.

Results:

Twelve apps that met the eligibility criteria were included in the parenting app directory. Parents

supported the idea of creating an app directory and recommended sharing the link in perinatal classes.

During design sessions, parents stressed the importance of an organized user interface, providing less but

the best choices to ease the search process for apps, reducing the number of clicks to save time, and mobile

optimization of the Website to accommodate different screen sizes.

Conclusions:

Contemporary parents’ use of apps is growing significantly; therefore, clinicians should

support parents’ search for quality apps and guide them accordingly. Parents can provide insight into design

principles that can be used in developing appealing parenting app resources. Parents should be involved in

designing future resources as they can signicantly contribute to ensuring a resource is useful.

Keywords:

Mobile applications; parenting apps; participatory design; webpage prototypes; user interface design

Received: 29 October 2020. Accepted: 19 April 2021; Published: 21 May 2021.

doi: 10.21037/ht-20-29

View this article at: http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/ht-20-29

11

^ ORCID: 0000-0001-8751-0756.

Health Technology, 2021Page 2 of 11

© Health Technology. All rights reserved.

Health Technol 2021;5:10 | http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/ht-20-29

released 325,000 apps on the marketplace which indicates

the increased number of choices available to users thus

worsening the search for evidence-based apps which

are comparatively very few and require more time and

resources to develop (9,10). Some researchers have reported

content credibility and security concerns as barriers to app

utilization (3,11,12). Many parents, however, overlook the

credibility of the content and security of the personal data

concerns due to the benets gained from using certain app

features such as customization of data (13-15).

The importance of an organized and functional user

interface cannot be denied in the effective utilization of

apps. Users generally evaluate apps on utility, functionality,

and security standards and if these requirements are not

met, they move on to the next app. Apps with poor first

impressions, poor design, lack of interactive features,

glitches, unnecessary personal information requests, and

malware alerts lose users quickly, receive low star ratings,

and poor user reviews, negatively affecting their search

ranking in the app store (16). Evidenced-based apps are

scientically robust; however, many lack parents-preferred

user interface elements and therefore, receive less attention

and low star ratings on the app store. For example, Virani

et al. (17) reported an evidence-based app had the lowest

number of downloads, overall lowest MARS (Mobile App

Rating Scale) score, and the lowest score on the MARS

engagement subscale compared to other 15 apps that

were included in the review. Hingle et al. (18) also found

that evidence-based apps frequently lacked visual appeal,

interactive features, and intuitive user interfaces.

Users learn to locate apps through trial and error

methods. Today’s parents have limited time to scroll through

hundreds of pages or apps, rather, they typically select from

the initial few search options. Poor searching skills (e.g.,

inappropriate search terms, unfamiliarity with advanced

search functions) often lead to irrelevant results that fail to

meet parents’ needs and quality expectations. Many parents

feel trapped in cycles of app searching, installing, trialing,

uninstalling, and starting over (19-21). Thus, there is a need

for a solution that provides parents easy and efcient access

to quality apps in a way that is preferred by parents.

While evidence-based apps have been developed to

better meet the needs of parents, these apps are difficult

for parents to locate due to their low visibility among the

plethora of parenting apps. Further, evidence suggests

that co-designing with the target population leads to more

relevant and useable technologies compared to products

developed on their behalf (22,23). Therefore, the purpose of

this study was twofold: (I) to engage parents in developing

a parenting app directory that contains the list and brief

information about quality parenting apps to support their

search for apps; and (II) to involve parents in designing

a user interface of Webpages featuring a parenting app

directory.

The rapid rate at which apps develop, update, and

disseminate requires constant maintenance of the existing

apps, and the addition of new apps to the directory. It is

difficult for the student investigator (primary author) to

keep up with this challenge and sustain the intervention;

therefore, the researchers partnered with an existing

parenting Website that provides resources to parents/

caregivers of children from birth to 8 years. The Website

hereafter refers to as the host Website. The participants

were asked to design only two Webpages; a landing page

and an app description page using the basic layout, color,

and design of the host Website. Participants were also

engaged in developing links supporting feedback on existing

apps and the addition of new apps in the future. The nal

prototypes were supposed to be part of the hosting Website

but, due to unforeseen circumstances, this plan was not

implemented.

Methods

Derived from participatory action research, participatory

design approaches to software design involve users

throughout the design process from identifying needs to

developing and testing the design product. The democracy

and empowerment of users of technology are the core

principles of participatory design (22,24). Appropriate

democratic participation empowers users by involving

them in technology-related decisions that affect their

lives in some way. Final design decisions are based on

consensual agreements between researchers and users. The

participatory design creates a sense of ownership among

users and empowers them as key stakeholders (23,25). To

involve participants throughout the process the project

was divided into three phases: app review, focus group

discussions, and Webpages prototyping. To address this

aim, the study had the following objectives: (I) to gain an

insight into available parenting apps and their quality by

performing an app review on the Google Play Store; (II)

to explore parents’ perceptions of available parenting apps

and involve them in the development of a parenting app

directory through focus group discussions; (III) to engage

parents in designing Webpages prototypes to feature the

Health Technology, 2021 Page 3 of 11

© Health Technology. All rights reserved.

Health Technol 2021;5:10 | http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/ht-20-29

parenting app directory.

Sample and setting

The study was conducted in accordance with the

Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study

was approved by Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board

(CHREB ID: REB17-2077) and informed consent was

taken from all the participants.

App review

The authors conducted an app review to gain insight into

current trends of parenting apps and their quality. The

authors found 4,300 apps on their initial search using

18 search terms: mum, mom, mommy, mama, mother,

father, dad, daddy, papa, newborn, baby, infant, kid, child,

children, family, parent, and parenting. Most apps were

of poor quality due to inadequate information/features,

lack of credible information/sources, navigation issues,

and excessive advertisements. Detailed ndings of the app

review have previously been published (17). Some of the

apps from the review were used in the next phase to explore

participants’ perceptions of available parenting apps.

Focus group discussions

The parenting app directory was developed in four focus

group discussions with a total of 18 first-time Canadian

parents of infants (birth-12 months) who owned a

smartphone and have used at least one parenting apps in

the past 6 months. The majority of the participants were

female (n=15) and between 31–40 years of age (n=14).

Most parents were married (n=17), born in Canada (n=12),

and on maternity leave (n=14) at the time of focus group

discussions. Parents were recruited via placing posters and

distributing study cards in community health centers, public

libraries, and in perinatal classes. A Facebook page was also

created to recruit parents. The focus groups were conducted

in public library meeting rooms in Calgary, Canada. Each

focus group lasted approximately 2 hours and explored

parents’ search for apps, their preferences, their desired

features in apps. While the detailed ndings of focus group

discussions are shared somewhere else (21), ndings that are

pertinent to the development of the parenting app directory

are described in this paper.

The apps for the directory were selected via two

strategies: First, during focus group discussions, parents

mentioned a few apps that they liked to use. The authors

evaluated those apps on MARS (Mobile App Rating Scale),

developed by a multidisciplinary team to appraise app

quality (26). Apps that scored 3 and above were added to the

directory. Second, during focus group discussions in one of

the activities, the moderator provided app cards (cards with

the name and icon of the app, and its purpose) and asked

parents to review one or two apps based on their interest.

After reviewing apps for 10–15 minutes, each participant

individually shared their feedback to the group and further

discussed each app with other participants including likes/

dislikes, pros/cons, and reason for inclusion or exclusion of

the particular app in the directory. The discussion ended

with the mutually agreed decision that whether the app

should be part of the directory or not. Apps that received

participants’ agreement for inclusion were further evaluated

on the MARS scale by researchers and only included in

the directory if they received a 3/5 or above score on the

MARS.

Design sessions

The primary author and 3 parents (2 fathers and 1 mother)

co-created the user interfaces for two Webpages in a

series of three sessions. The prototype designing sessions

were conducted online using SMART kapp™ technology.

The SMART kapp™ technology is consists of a SMART

kapp™ digital whiteboard and a SMART kapp™ app,

that allows real-time sharing and editing of the drafts

created by the moderator on the whiteboard. For details

about this technology please visit https://www.smarttech.

com/. Prior to the designing session, the moderator sent

a link to download The SMART kapp™ app, a link for

the designing space (Figure 1), and examples of a few app

directories. On the day of the designing session, participants

were connected using the SMART kapp™ technology.

The moderator incorporated participants’ feedback on the

SMART kapp™ digital whiteboard which participants could

see on their SMART kapp™ app in real-time.

The design sessions were video recorded and analyzed

using agile development methodology after each session

by the researchers to incorporate parents’ suggestions.

Agile development methodology is a pragmatic approach

to design that is rapid, exible, iterative, and heavily relies

on integrating users’ feedback (27). After finalizing the

whiteboard prototyping drafts, the moderator developed

the interactive prototype in Wix, a free Website builder,

and sent the link via email to participants for review. The

prototypes were further modified based on participants’

feedback.

Health Technology, 2021Page 4 of 11

© Health Technology. All rights reserved.

Health Technol 2021;5:10 | http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/ht-20-29

Results

The results section is divided into 2 parts: parenting app

directory and user interface designing.

Parenting app directory

The focus group discussions revealed 34 apps and 18

parents reviewed a total of 20 apps during focus group

discussions. After removing duplicates (n=14), 12 apps

were selected for the app directory by using the following

criteria. Apps were considered ineligible if they were paid

(n=4); mostly used in pregnancy (n=4); needed a device to

operate (n=2); targeting sick kids (n=1); non-parenting apps

(n=5); voted out by participants (n=10) and; scored less

than 3 on MARS (n=7). Apps were divided into categories

as suggested by participants to ease the searching process.

The list of eligible apps, their categories, MARS scores, and

purposes are presented in Table 1.

To explore the viability of creating a parenting app

directory to support parents’ search for apps, at the end of

the focus group discussions, participants were asked to share

their feedback. All participants agreed that the parenting

app directory will support parents in nding quality apps.

One mother (age 39 years) said: “I like the idea because I

usually Google top apps for whatever and I get the list of 10

things and go through it… It’s basically just centralizing it…

and I think one thing for me is that it will give you the things to

search for, so it might actually help to look up things.”

While reviewing apps during the focus group discussions

many parents were excited and surprised to learn about

the different types of apps to assist them with their day-to-

day parenting concerns, such as sign language app. They

felt the Website would be a good resource for parents to

learn about new apps. One mother (age 29 years) shared her

feeling while reviewing a breastfeeding information app, “I

wish I had that [info for nursing mum app] when I rst started

doing breastfeeding. Most of the information is for the rst life

months when you need it the most.” One father (age 35 years)

shared his thoughts about a tracking app, “That (tracking

app) looks useful, and if we did know about that we would have

probably used it.” Another mother (age 29 years) commented

while presenting an app review to the group on a sign

language app, “I had never thought (about a sign language app)

and I’m happy that I did try one.”

Parents suggested that the parenting app directory link

Figure 1 Designing space.

Health Technology, 2021 Page 5 of 11

© Health Technology. All rights reserved.

Health Technol 2021;5:10 | http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/ht-20-29

should be promoted in prenatal classes to make parents

aware of these online resources in advance. As one mother

(age 29 years) said, “If the Website link is given in the…

parenting prep classes, then they (to be parents) will have time to

look through those before the baby is born.”

User interface designing

During focus group discussions and design sessions,

parents provided several suggestions to design a usable user

interface for the Webpages. See Table 2 for the suggestions

and supporting quotations from participants. Participants

co-created two Webpages prototypes: a landing page for the

list of apps included in the directory and the app description

page for each app.

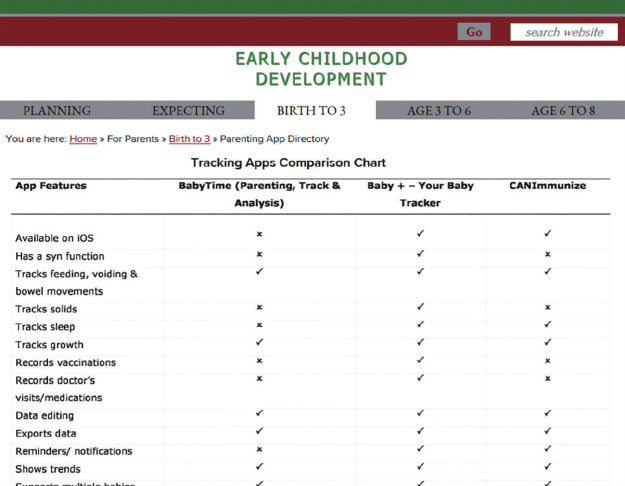

Landing webpage prototype

The landing page features the app directory and provides

a list of apps. See Figure 2 for the landing Webpage

prototype. Parents suggested categorizing apps and placing

three apps in one row to permit a glance of the available

apps in a specific category. The directory has two active

links. The rst link takes users to an app comparison chart

for each category. The comparison chart allows parents

to compare app features in a category and select an app

based on their preferences. As one mother (age 32 years)

said: “I really like the comparison idea. It is definitely handy

to see everything in comparison like that.” See Figure 3 for a

comparison chart. The second link is labeled as “read more”

which takes parents to the app description page and allows

parents to learn more about the app. One mother (age

32 years) commented on the importance of having a short

app description accompanied by a ‘read more’ link, said: “The

number of apps I have seen I kinda guess what this app is, but I

am not sure exactly what it is for? So, a shorter description with a

link to read more will help.”

As mentioned earlier the resource will also involve

parents in commenting on existing apps and the addition of

new apps. To engage parents, two links, ‘comment board’

and ‘recommend an app’ can be added to the host Website’s

Quick Links section. The comment board allows parents to

comment on the app’s current status and view other parents’

feedback on apps. The ‘recommend an app’ link permits

parents to suggest apps that they would like to share with

other parents. However, when parents suggest an app,

they will receive a message “Thank you for recommending an

Table 1 List of parenting apps included in the directory

Apps Category MARS score Purpose

BabyTime Tracker 4.5 It tracks infants’ activities and also provides lullabies and white

noises.

Baby + – Your Baby Tracker Tracker 4.4 It tracks infants’ activities and also offers lullabies, white noises,

and a baby book.

CANImmunize Tracker 3.8 It records, tracks and provides information on immunizations.

Baby and Child First Aid Information 4.5 It provides information on emergency and first-aid and also

records medications, allergies, emergency, and doctors’ contacts.

Info for Nursing Mum Information 4.4 It mostly provides information on breastfeeding.

BabyCenter Information 4.4 It provides information on a wide range of parenting topics and

also offers a baby book and parenting forums.

WebMD Baby Information 4.4 It provides information on health-related matters and also offers a

baby book and a basic tracker.

Babybrains Information 4.0 It provides information on brain development activities.

Don’t Cry My Baby (lullaby) Sleeping-aid 4.5 It provides white noises and lullabies.

Baby Sleep - White Noise App Sleeping-aid 4.3 It provides white noises and lullabies.

ASL Dictionary for Baby Lite Miscellaneous 4.4 It supports teaching and learning of sign language.

Baby Weaning and Recipes Miscellaneous 4.3 It provides recipes and information on baby weaning.

MARS, mobile app rating scale.

Health Technology, 2021Page 6 of 11

© Health Technology. All rights reserved.

Health Technol 2021;5:10 | http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/ht-20-29

app. Our team will evaluate the app and it will be posted on the

directory if it meets the quality standards.” This additional step

will ensure that only quality apps are added to the directory.

As one father (age 33 years) stated: “People can submit all

kinds of app... and every time someone sends an app, you have to

make sure that it is relevant, reviewed and placed in the right

category. It has information that is reputable.”

Participants also suggested that it would be nice to have

a link for interested parents who would like to know the

process of app selection. To accommodate this request ‘how

we assess apps’ can be added to the ‘Quick Link’ section to

let interested parents learn about the app selection process

for the directory.

App description webpage prototype

The app description page is specific to each app and

describes the app briefly to assist parents in selecting

apps based on their preferences. See Figure 4 for the app

description page. Participants suggested an organized

interface with less repetition from the app store description

page. Parents felt that the availability of the app in multiple

languages was important information that is often not

showcased and should be available next to the app icon

on the app description page. As one father (age 35 years)

stated: “English is her (my wife’s) second language, or for

people who have recently moved here, their English might

not be as good. Everything in the app store is in English,

and it would be nice to know if it is available in additional

languages like French or German.”

The app rating was another important piece of

information that parents used to decide whether an app

is worth trying before going through the details. One

mother (age 32 years) said: “I would like to see, app rating

without having to click on the app store.” Participants felt that

a link from the app store description page to download

would be sufficient for interested parents to get detailed

information about the app from the app store. Participants

recommended a pros and cons chart for each app that would

permit parents to have a quick glance at apps’ potentials

and facilitate their decision to download. One father (age

33 years) commented: “If you have 20 apps and you don’t want

to download all of them to try and see which one is good. These

pros and cons can help you decide whether to download it or not.”

Participants also suggested adding the review details at the

bottom including app ratings, date of review, and link to any

research studies or expert review if available. For example,

one father (age 33 years) said: “I like the review details in the

end, it tells me that the app is updated and someone is responsible

Table 2 Parents’ suggestions for designing a usable user interface and supporting quotations

Suggestions Participant’s words

Apps should be presented in categories to ease

the search process.

“I think the categories would work well that would be the best (mother, age 32 years).

There should be a maximum of three best

apps in one category; too many apps with

similar features in one category were deemed

overwhelming.

“I would recommend you to include two to three apps that have the best ratings (mother,

age 36 years).

“They gonna be lost if you put 50 or 60 apps on that main page (mother, age 37 years).

Use of an organized interface; busy and chaotic

Webpages were considered “annoying and took

longer to find desired parenting material.

“I just find if there is too much on there and I have to search through a bunch of things

to find what I'm looking for then I just get frustrated (mother, age 33 years).

Mobile optimization of the Website as parents

used smartphones more than any other device

due to its smaller size.

“If the website is mobile optimized then three [apps] in a row is fine. If not, then it will

be very difficult and a long row to see on a small screen You know 80% of your traffic

comes from mobile so make sure it is mobile optimized (father, age 35 years).

Avoid repetition of the content on the

Webpages; fewer words and use of images

were recommended to convey the message.

“You can check app-specific comments on the app store. No need to duplicate that

here (father, age 33 years).

“I just don’t want you to duplicate what’s on the app store (father, age 35 years).

Reduce the number of clicks; more clicks waste

time and deters parents from using the resource

effectively.

One father commented on other fathers’ disagreement on adding another click: “I

agree, there will too many clicks and it will be confusing (father, age 35 years).

“If I am on the computer, I don’t mind the clicks but if I am on the phone, I definitely

want less clicks (mother, age 32 years).

Health Technology, 2021 Page 7 of 11

© Health Technology. All rights reserved.

Health Technol 2021;5:10 | http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/ht-20-29

for the update.”

Discussion

This study engaged Canadian parents of infants in

developing a parenting app directory and in designing

Webpages that featured the directory to ease their search

for apps. It is well established that there is an abundance

of online parenting material and it is difficult for parents

to find quality resources (8,17,28). The developed app

directory centralizes the apps on one Webpage thus

creating a one-stop-shop for parents looking for quality

parenting apps. Slomian et al. (29) utilized a similar idea and

centralized Websites in the French language for mothers of

children under 1 year of age. They found that the Website

was a useful solution in addressing mothers’ information

needs, especially during the postpartum period.

Changes in current trends of dual-parent working

families have affected parents’ time availability. Time

constraints force parents to make quick decisions in selecting

and using an online resource. Ryan et al. (30) found 42% of

the parents never accessed a Website developed to support

them with ADHD, reporting lack of time as a major barrier.

Similarly, in this study parents frequently mentioned time

constraints in accessing and evaluating online material and

recommended time-saving interface elements such as an

organized homepage, categorization of the content, less text,

synopsis accompanied with ‘read more’ link for interested

users, and mobile-optimized Website. Andrew et al. (31)

indicated time-saving design is on the rise due to a gradual

shortening attention span in humans. One of the most

important features of the time-saving design is a homepage

that is content-oriented, context-specific and highlights

only the most relevant information thus minimizing users’

time spent on other distracting features and guide users to

subsequent Webpages based on their preferences.

First-time parents who are already overwhelmed with

the responsibilities of an infant nd it further overwhelming

to select a quality resource from the infinite app choices

available to them. Laja (32) stated in this world of

Figure 2 Main or landing webpage.

Health Technology, 2021Page 8 of 11

© Health Technology. All rights reserved.

Health Technol 2021;5:10 | http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/ht-20-29

unlimited choices, designers need to eliminate options for

users. A huge number of choices distract users and they

end up choosing nothing. In this study parents also felt

overwhelmed with the abundance of app choices in one

category and recommended to include only three top apps

in a category.

The participatory design provides the opportunity to

engage users in designing a resource that works for them.

Technology products that are designed in partnership with

end-users meet their expectations and increase the uptake of

the developed resource. Abbass-Dick et al. (33) designed and

evaluated an eHealth breastfeeding resource with Canadian

Indigenous mothers using participatory design. They found

that involving mothers in co-creating the resource resulted

in a culturally relevant Website that met their needs and

was appreciated by the participants. Similarly, in this study

using a participatory design approach, parents participated

in selecting the apps for the directory and suggested the

user interface elements that are relevant to busy and

overwhelmed parents and can simplify their search for apps.

Implication for practice

The growing trend of parents’ use of apps and the

proliferation of poor quality and irrelevant apps presented a

timely opportunity to design an online resource for parents

supporting their search for apps. Clinicians need to support

technologically savvy parents in a way that they like to

receive information rather than the way health professionals

used to deliver information.

Danbjørg et al. (34) designed an app for postnatal parents

and indicated parents were comfortable with app use and

found it easy to use compared to other methods such as

consulting nurses over the phone. However, nurses reported

feeling incompetent while interacting with parents using

the app due to unfamiliarity with digital modes of delivering

information. Researchers and clinicians’ participation in

evaluating and suggesting apps can support parents’ use of

quality resources.

Co-creating resources with end-users not only provide

insight into issues that users are facing but also provides

ideas of dealing with the issue in a way that is appealing to

users. Research methods such as participatory design can be

used in exploring the target population’s specic concerns

and developing an online resource that suits their needs

and meets their expectations. Researchers should consider

involving parents throughout the process from identifying

their needs to evaluating the end-product. Davis et al. (28)

also recommended that nurses should actively participate

in involving parents and other multidisciplinary teams in

developing evidence-based resources that are acceptable to

parents.

Figure 3 App comaprssion chart. The information presented here is not factual.

Health Technology, 2021 Page 9 of 11

© Health Technology. All rights reserved.

Health Technol 2021;5:10 | http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/ht-20-29

Figure 4 App description page.

Users may not be theoretically equipped with design

knowledge but they can provide insight into design principles

that may be used in developing an appealing resource for

the target populations. For example, in this study parents

indicated that infant care responsibilities account for a huge

amount of their time and suggested using time-saving user

interface design elements to ease the search process for

parents. Researchers can use this as a guide in developing

future online resources targeted to parents and incorporate

design elements that are relevant to parents.

Limitations

The study has a few limitations that need to be considered

while interpreting findings. The high representative

sample of mothers may not have very well captured fathers’

perception in this study. However, involving fathers in

research is a challenging task that has been mentioned by

several researchers (35-37). In the future, a parenting app

study that would involve a greater number of fathers may

provide a different insight into the matter. As the directory

was supposed to be part of the host Website to sustain the

intervention, participants were given a designing space with

predefined basic layout that restricted their feedback on

certain design elements such as color, images, and so on.

Future studies that incorporate parents’ preferences of the

basic layout will add signicantly to the body of parenting

user interface design literature.

Conclusions

Today’s parents are driven by the need for time and access

Health Technology, 2021Page 10 of 11

© Health Technology. All rights reserved.

Health Technol 2021;5:10 | http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/ht-20-29

to resources that are convenient, efficient, and freely

available. In this study, parents co-created a user interface

with researchers to feature the app directory to support

their search for apps. Parents consistently advocated for

time-saving design features, such as a less cluttered and

easier to navigate user interface that provides less but the

best choices in a particular parenting app category, to

incorporate the resource in their busy lives. Current trends

depicting a constant increase in accessing apps to resolve

parenting concerns, demand clinicians’ and researchers’

participation in supporting parents’ search for quality online

resources. Involving parents in research and gaining their

perspectives on developing online resources will result in

well-targeted technology products and will increase uptake

amongst parents. Technology that is developed with users

has a more powerful impact than those developed on behalf

of them. This study provided insight into parents’ preferred

user interface features that can be used in designing future

online resources.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Eleni Stroulia,

Professor, Faculty of Science, University of Alberta, for her

contribution to the conception and design of the project as

one of the supervisory committee members.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Data Sharing Statement: Available at http://dx.doi.

org/10.21037/ht-20-29

Conicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE

uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.

org/10.21037/ht-20-29). The authors have no conflicts of

interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all

aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related

to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are

appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was

conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki

(as revised in 2013). The study was approved by Conjoint

Health Research Ethics Board (CHREB ID: REB17-2077)

and informed consent was taken from all the participants.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article

distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons

Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International

License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-

commercial replication and distribution of the article with

the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the

original work is properly cited (including links to both the

formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license).

See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

1. Jang J, Dworkin J, Hessel H. Mothers’ use of information

and communication technologies for information seeking.

Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 2015;18:221-27.

2. Brisson-Boivin K. The digital well-being of Canadian

families (MediaSmarts) 2018. Available online: https://

mediasmarts.ca/sites/mediasmarts/les/publication-report/

full/digital-canadian-families.pdf

3. Asiodu IV, Waters CM, Dailey DE, et al. Breastfeeding

and use of social media among rst-time African American

mothers. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2015;44:268-78.

4. Shorey S, Dennis C, Bridge S, et al. First-time fathers’

postnatal experiences and support needs: a descriptive

qualitative study. J Adv Nurs 2017;73:2987-96.

5. Chin K. Prospective data collection for feeding difculties

and nutrition. Boston, MA: Boston University, 2018.

6. Lupton D. The use and value of digital media for

information about pregnancy and early motherhood:

a focus group study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth

2016;16:171.

7. Pehora C, Gajaria N, Stoute M, et al. Are parents getting

it right? a survey of parents’ internet use for children’s

health care information. Interact J Med Res 2015;4:e12.

8. Taki S, Campbell KJ, Russell CG, et al. Infant feeding

websites and apps: A systematic assessment of quality and

content. Interact J Med Res 2015;4:e18.

9. Jake-Schoffman DE, Silfee VJ, Waring ME, et al. Methods

for evaluating the content, usability, and efcacy of

commercial mobile health apps. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth

2017;5:e190.

10. Pham Q. Innovative research methods to evaluate effective

engagement with consumer mobile health applications

for chronic conditions.. Toronto, Canada: University of

Toronto, 2019. Available online: https://search.proquest.

com/openview/40715d4f51068341841a24ee7ae9a172/1?

pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y

11. Friedman LB, Silva M, Smith K. A focus group study

observing maternal intention to use a WIC education app.

Health Technology, 2021 Page 11 of 11

© Health Technology. All rights reserved.

Health Technol 2021;5:10 | http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/ht-20-29

Am J Health Behav 2018;42:110-23.

12. Zhao J, Freeman B, Li M. How do infant feeding apps in

china measure up? A content quality assessment. JMIR

Mhealth Uhealth 2017;5:e186.

13. Lupton D, Pedersen S. An Australian survey of women’s

use of pregnancy and parenting apps. Women and Birth

2016;29:368-75.

14. Sunyaev A, Dehling T, Taylor PL, et al. Availability and

quality of mobile health app privacy policies. J Am Med

Inform Assoc 2015;22:e28-33.

15. Wicks P, Chiauzzi E. ‘Trust but verify’--ve approaches to

ensure safe medical apps. BMC Med 2015;13:205.

16. Sanhz J. Why do people uninstall the apps? 2016. Available

online: https://www.quora.com/Why-do-people-uninstall-

the-apps

17. Virani A, Duffett-Leger L, Letourneau N. Parenting apps

review: In search of good quality apps. mHealth 2019;5:44.

18. Hingle M, Patrick H. There are thousands of apps for

that: navigating mobile technology for nutrition education

and behavior. J Nutr Educ Behav 2016;48:213-8.e1.

19. Chidgey C. Mobile app discovery challenges 2015.

Available online: http://www.gummicube.com/

blog/2015/07/mobile-app-discovery-challenges/

20. Tinschert P, Jakob R, Barata F, et al. The potential of

mobile apps for improving asthma self-management: a

review of publicly available and well-adopted asthma apps.

JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2017;5:e113.

21. Virani A, Duffett-Leger L, Letourneau N. Parents’

perspectives of parenting app use. J Inform Nurs

2020;5:8-18.

22. Halskov K, Hansen NB. The diversity of participatory

design research practice at PDC 2002–2012. Int J Hum

Comput 2015;74:81-92.

23. Wolstenholme D, Ross H, Cobb M, et al. Participatory

design facilitates person centred nursing in service

improvement with older people: A secondary directed

content analysis. J Clin Nurs 2017;26:1217-25.

24. Bratteteig T, Wagner I. Unpacking the notion of

participation in participatory design. CSCW Conf Comput

Support Coop Work 2016;25:425-75.

25. Andersen LB, Danholt P, Halskov K, et al. Participation

as a matter of concern in participatory design. CoDesign

2015;11:250-61.

26. Stoyanov SR, Hides L, Kavanagh DJ, et al. Mobile app

rating scale: a new tool for assessing the quality of health

mobile apps. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2015;3:e27.

27. Lan C, Kannan M, Peng X, et al. A framework for

adapting agile development methodologies. Eur J Inf Syst

2009;18:332-43.

28. Davis DW, Logsdon MC, Vogt K, et al. Parent education

is changing: a review of smartphone apps. MCN Am J

Matern Child Nurs 2017;42:248-56.

29. Slomian J, Vigneron L, Emonts P, et al. The “Happy-

Mums” website dedicated to the perinatal period:

Evaluation of its acceptability by parents and professionals.

Midwifery 2018;66:17-24.

30. Ryan GS, Haroon M, Melvin G. Evaluation of an

educational website for parents of children with ADHD.

Int J Med Inform 2015;84:974-81.

31. Andrew P. The time-saving design trend & how to use

it 2019. Available online: https://speckyboy.com/time-

saving-design-trend/

32. Laja P. 8 Web design principles to know in 2019 2019.

Available online: https://conversionxl.com/blog/universal-

web-design-principles/

33. Abbass-Dick J, Brolly M, Huizinga J, et al. Designing

an eHealth breastfeeding resource with indigenous

families using a participatory design. J Transcult Nurs

2018;29:480-8.

34. Boe Danbjørg D, Wagner L, Rønde Kristensen B, et al.

Nurses’ experience of using an application to support new

parents after early discharge: an intervention study. Int J

Telemed Appl 2015;2015:851803.

35. Balu R, Lee S, Steimle S. Encouraging attendance

and engagement in parenting programs: Developing a

smartphone application with fathers, for fathers 2018

Available online: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/

les/opre/b3_dadtime_brief_508.pdf

36. Lee SJ, Walsh TB. Using technology in social work

practice: the mDad (mobile device assisted dad) case study.

Advances in Social Work 2015;16:107-24.

37. White BK, Giglia RC, Scott JA, et al. How new and

expecting fathers engage with an app-based online forum:

Qualitative analysis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2018;6:e144.

doi: 10.21037/ht-20-29

Cite this article as: Virani A, Duffett-Leger L, Letourneau N.

Co-designing an e-resource to support’ search for mobile apps.

Health Technol 2021;5:10.