I

ran has experienced dramatic demographic

change in the last decade. Levels of childbear-

ing have declined faster than in any other

country, and maternal and child health have great-

ly improved. These changes have coincided with

the revival of the national family planning pro-

gram, which is delivered through a nationwide

network of primary health care facilities. Many

observers have wondered how such a dramatic

increase in contraceptive use could have occurred

in a traditional society ruled by Islamic law.

Demographic Trends

Iran’s population increased from 34 million in

1976 to nearly 50 million in 1986, with an aver-

age growth rate of 3.9 percent per year (3.2 per-

cent from natural increase and 0.7 percent from

immigration); a decade earlier, the average annual

growth rate had been 2.7 percent. But the rise in

the population growth rate that occurred during

and after the 1979 Islamic revolution in Iran was

followed by a sharp decline. Between 1986 and

1996, the population growth rate dropped to 2.0

percent per year.

1

Currently, Iran’s population is

estimated to be growing by 1.2 percent a year.

The population growth rate has been declin-

ing because of the dramatic change in Iranian

women’s fertility: According to the Iranian min-

istry of health, the country’s total fertility rate

declined from 5.6 births per woman in 1985 to

2.0 births in 2000 (Figure 1). Iran’s fertility

decline is particularly remarkable in how quickly

it occurred in rural areas. Between 1976 and

2000, the total fertility rate in rural areas declined

from 8.1 births per woman to 2.4 births per

woman. The fertility of urban women declined

from 4.5 births to 1.8 births per woman during

the same period.

2

Figure 2 (page 2) shows how

fertility rates in Iran vary by province.

The decline in fertility has mainly been due

to the increase in contraceptive use among mar-

ried women: In 2000, 74 percent of married

women practiced family planning, up from 37

percent in 1976. The change in marriage patterns

has also affected fertility: Women’s average age at

first marriage increased from 19.7 in 1976 to

22.4 in 1996.

IRAN’S FAMILY PLANNING PROGRAM:

RESPONDING TO A NATION’S NEEDS

POPULATION REFERENCE BUREAU

by Farzaneh Roudi-Fahimi

Iran MoroccoEgypt Turkey

1985 2000 1987 19971988 2000 1988 1998

5.6

2.0

4.4

3.5

4.8

3.2

3.0

2.6

Births per woman

Figure 1

Trends in Total Fertility Rates for

Selected Countries

NOTE: Rates for Iran are based on data from the ministry of health and

medical education. The Statistical Center of Iran has reported that fertility

fell from 7.1 births per woman in 1986 to 2.5 births per woman in 2001.

SOURCE: Population Reference Bureau database, based on selected

national surveys.

This overview of Iran’s family planning efforts and the role of the Islamic government and civil

society in the revival of the national family planning program is the second in a series of policy briefs

from the Population Reference Bureau. This series analyzes population, environment, reproductive

health, and development linkages within the framework of the Cairo Programme of Action and the

cultural contexts of population groups in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). Future briefs

on MENA will cover specific population-related topics or country case studies.

Evolution of Iran’s Family

Planning Program

There are three distinct periods in the history of

Iran’s family planning program, each marked by

major changes in the government’s policy.

3

Family Planning Before the 1979 Islamic

Revolution

Iran was one of the first countries to establish a

family planning program as part of its develop-

ment plan. The Imperial Government of Iran

adopted a national family planning policy in

1966, and launched an active family planning

program in the ministry of health in 1967. The

1967 Tehran Declaration acknowledged family

planning as a human right and emphasized its

social and economic benefits for families and soci-

ety.

4

The program recruited and trained a cadre of

professional staff, and taught many young doctors

about family planning’s implications for public

health and its critical role in improving the well-

being of women and children.

Family planning became an integral part of

maternal and child health services nationwide. By

the mid-1970s, 37 percent of married women

were practicing family planning, with 24 percent

using modern methods. The total fertility rate,

although declining, remained high, at more than

six births per woman.

The Islamic Revolution and Pronatalism

The family planning program was dismantled soon

after the 1979 Iranian Revolution, because the

program was associated with the Iranian royal

family and was viewed as a Western innovation.

The new government advocated population

growth, and adopted new social policies, including

benefits such as allowances and food subsidies for

larger families. In an attempt to ensure continued

government support for family planning, a num-

ber of committed health professionals approached

the government with information about the health

benefits of family planning. They even obtained

fatwas (religious edicts concerning daily life) from

Imam Khomeini and other top-ranking clerics to

the effect that “contraceptive use was not inconsis-

tent with Islamic tenets as long as it did not jeop-

ardize the health of the couple and was used with

the informed consent of the husband.”

5

In 1980, Iran was attacked by Iraq. During

the eight-year conflict that followed, having a large

population was considered an advantage, and

population growth became a major propaganda

issue. Many Iranian officials were pleased when the

1986 census showed that Iran’s population of close

to 50 million was growing by more than 3 percent

per year, one of the highest rates in the world.

6

At the same time, the Plan and Budget

Organization, which is the main government

agency responsible for monitoring government

revenues and expenditures, and other ministries,

such as health, education, and agriculture, were

aware of the economy’s vulnerability and the

added difficulties caused by a rapidly growing

young population. To assess the economic dam-

ages of the war and prepare for a national devel-

opment plan, the Plan and Budget Organization

collected data on issues such as employment and

demand for basic services. The assessment painted

a grim picture of the country’s economy.

PRB MENA Policy Brief 2002

2

SISTAN-BALUCHISTAN

KERMAN

FARS

KHUZISTAN

ILAM

MARKAZY

QOM

HAMADAN

GHAZVIN

ZANJAN

KURDISTAN

ARDEBIL

GILAN

YAZD

ESFAHAN

GOLESTAN

KHORASAN

B

O

O

S

H

E

H

R

HORMOZGAN

TEHRAN

LORISTAN

SEMNAN

MAZANDARAN

AZARBAIJAN E.

CHAHARMAHAL

KOHGILUYEH

Births per woman

A

Z

A

R

B

A

IJ

A

N

W

.

KERMANSHAH

1.4–2.2 (Below or at replacement)

2.3–2.9

3.0 and up

Figure 2

Total Fertility Rate by Province, Iran, 2000

SOURCE: Iranian Ministry of Health and Medical Education et al., Demographic and Health Survey,

Iran 2000, Preliminary Draft Report (2002).

After the war with Iraq ended in 1988, as the

government began to prepare its first national

development plan, the Plan and Budget Organiza-

tion alerted top government leaders that the

nation’s dwindling resources could not both sup-

port the high cost of reconstruction and provide

the social and welfare services stipulated by the

new constitution. In response, the prime minister

asked all government departments to review the

population growth rate’s impact and implications

for the first development plan (which would

take effect in 1989). Later, he declared that the

government was “reconsidering the issue of

population growth.”

7

Restoring the Family Planning Program

Having convinced many top policymakers of the

importance of family planning, the Plan and

Budget Organization and the ministry of health

and medical education decided to launch a publici-

ty campaign to convince other members of the pol-

icy elite and the general public about the need for a

national population policy. The much-publicized

three-day Seminar on Population and Development

was held in Mashad in September 1988.

The Iranian media helped disseminate the

seminar’s main message: Iran’s population growth

rate was too high and, if left unchecked, would

have serious negative effects on the national econo-

my and the welfare of the people. Participants at

the seminar strongly urged the government to con-

sider population issues during policymaking. At a

press conference at the end of the Mashad seminar,

the minister of health and medical education reit-

erated the late Imam Khomeini’s fatwa regarding

family planning, and announced that the Islamic

Republic of Iran would establish a family planning

program. In December 1988, the High Judicial

Council declared that “there is no Islamic barrier

to family planning.”

8

The Mashad seminar was mainly a profes-

sional and technical gathering; the influential

clergy (ulama) outside the central government

were not involved in the seminar’s deliberations.

To ensure that the proposed policy would have

the clergy’s support, family planning was singled

out for special consideration and discussion at the

February 1989 seminar on “Islamic Perspectives

in Medicine,” which was attended by eminent

clergy and physicians.

Despite these efforts, some influential clergy

were not convinced about the potential effects of

rapid population growth or that public investment

in family planning was consistent with the basic

tenets of Islam.

9

To overcome these objections, the

government took the issue to the Expediency

Discernment Council of the System, which resolves

disputes between parliament and the Guardian

Council. The Expediency Council confirmed that

family planning and population policies were legiti-

mate areas for government involvement, paving the

way for the reintroduction of a national population

policy and the family planning program.

The Revitalized Family

Planning Program

The family planning program, officially inaugu-

rated in December 1989, has three major goals: to

encourage families to delay the first pregnancy

and to space out subsequent births; to discourage

pregnancy for women younger than 18 and older

than 35; and to limit family size to three children.

The ministry of health and medical education has

been given almost unlimited resources to provide

free family planning services to all married cou-

ples, promote small families as the norm, and help

couples prevent unplanned pregnancies. All mod-

ern contraceptive methods are available to married

couples, free of charge, at public clinics. In 1990,

to remove continuing doubts about the accept-

ability of sterilization as a method of family plan-

ning, the High Judicial Council declared that

sterilization of men and women was not against

Islamic principles or existing laws.

In 1993, the legislature passed a family plan-

ning bill that removed most of the economic

incentives for large families. For example, some

allowances to large families were cancelled, and

some social benefits for children were provided for

only a couple’s first three children. The law also

gave special attention to such goals as reducing

infant mortality, promoting women’s education

and employment, and extending social security

and retirement benefits to all parents so that they

would not be motivated to have many children as

a source of old age security and support.

While all these legal reforms in support of the

family planning program are significant, high-

lighting Iran’s commitment to slowing population

growth, there has been no assessment of the laws’

PRB MENA Policy Brief 2002

3

implementation or their impact on lowering fertil-

ity. The level and speed of the decline in fertility

have been beyond any expectation. The first offi-

cial target of the revitalized family planning pro-

gram, as reflected in the government’s first

five-year development plan, was to reduce the

total fertility rate to 4.0 births per woman by

2011.

10

By 2000, the rate was already down to

half the stated goal, at 2.0 births per woman.

Population and health experts close to the

program attribute its success largely to the govern-

ment’s information and education program and to

a health care delivery system that was able to meet

reproductive health needs. Family planning is one

of many health services provided by the system,

which is based on different levels of care and an

established referral system (see Box 1 for more on

care delivery in rural areas). Overall family plan-

PRB MENA Policy Brief 2002

4

Iran’s rural health care network is the cornerstone of the

country’s health care system. The network evolved out

of a series of pilot projects that were conducted in the

early 1970s as part of an effort to find the best system

for expanding medical and health services in rural areas.

(Iran’s rural population is widely dispersed: In 1996,

more than 68,000 villages had an average population

of 340 people.) The result was the establishment of

rural “health houses,” based on the idea that vaccine-

preventable diseases, acute respiratory infections, and

diarrheal diseases can be addressed by making simple

technology and information available to even minimally

trained personnel.

There are now more than 16,000 health houses in

Iran, covering around 95 percent of the rural population;

mobile clinics bring health services to people living in

remote areas. Each health house serves around 1,500

people, usually consisting of the people of one central

village (where the health house is located) and those of

satellite villages that are within an hour’s walk from the

central village. Each health house generally has two

health providers (in principle, one man and one

woman), known as behvarzes, who receive two years of

training. The female behvarz is in charge of maternal and

child health care, and the male is responsible for issues

related to environmental health, such as water safety and

agricultural production. Behvarzes must be local resi-

dents; the requirement is particularly important for

women behvarzes, who can continue to live in their

home village while working. Since behvarzes are local,

they tend to stay in the job and to know their clients.

One of the first tasks of a behvarz team is to take a

population census of the villages for which their health

house is responsible. The census is repeated at the

beginning of each Iranian calendar year (March 21).

The age and sex profiles of each village are put in charts.

Summary tables of these data are posted on the wall of

each health house and are updated each month. For

example, data can show the number of children who

have been born since the beginning of the year, the pro-

portion who have been vaccinated, and the number who

died, by cause of death. The data also show the number

of married women of reproductive age and their contra-

ceptive prevalence rate by method. Behvarzes are proac-

tive: They are comfortable knocking on people’s doors

to talk about families’ health care needs, including fami-

ly planning, and to give them appointments to visit the

health house.

Box 1

Iran’s Rural Health Care Network

Rural health providers, know as behvarzes, maintain up-

to-date records on the health and well-being of people in

rural villages. Here, two behvarzes from central Iran are

shown in front of their clinic’s charts on local health.

FARZANEH ROUDI-FAHIMI

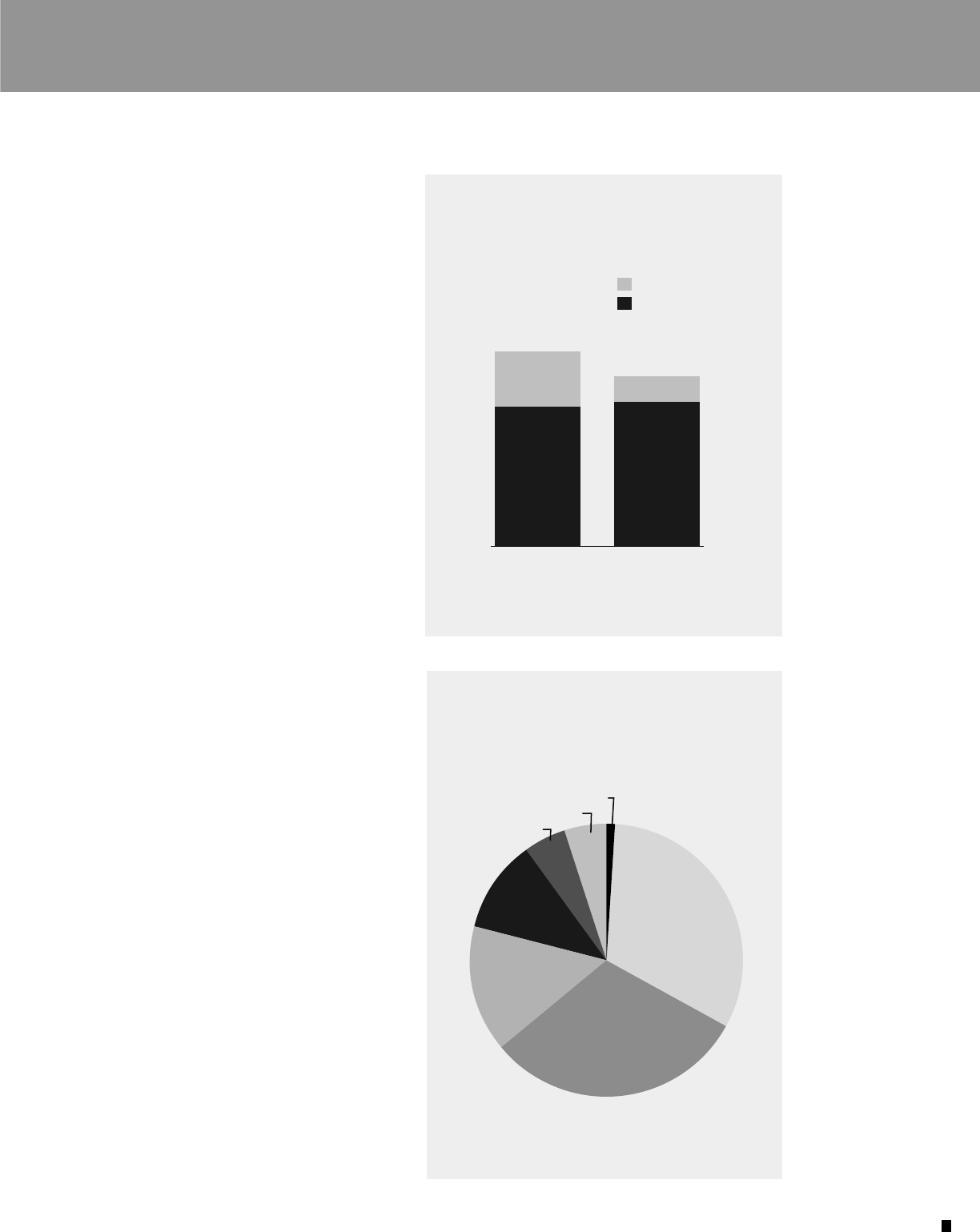

ning practice is higher among women living in

urban areas than among those living in rural areas,

but the use of modern contraceptive methods is

about the same in both urban and rural areas

(see Figure 3). Contraceptive pills are the most

popular modern method, followed by female

sterilization (see Figure 4).

The program has succeeded in removing both

cultural and economic barriers to family planning,

and the information and education campaign has

assured the public that family planning is consis-

tent with Islamic tenets and does not threaten

family values (see Box 2, page 6). By providing

free family planning services, the program has

given low-income couples in both rural and urban

areas access to services that would otherwise be

too expensive for most families. In 2000, the min-

istry of health and medical education provided 75

percent of all family planning services (91 percent

of services in rural areas and 67 percent of services

in urban areas). The question the ministry now

faces is whether the government needs or can even

afford to continue to be so involved in providing

family planning services, since small families and

contraceptive use are now the norm. In the next

10 years, the number of reproductive-age women

will grow by more than 20 percent.

Population education is part of the curricu-

lum at all educational levels; university students,

for example, must take a two-credit course on

population and family planning. Family planning

is also included in the country’s adult literacy

campaign. Couples who are planning to marry

must participate in government-sponsored family

planning classes before receiving their marriage

license. The classes are mandatory for both

prospective brides and grooms, supporting the

family planning program’s goal of increasing male

involvement and responsibility in family planning.

The family planning program, which is attempt-

ing to increase men’s participation in family plan-

ning, uses more than just education to support

men’s involvement: The Middle East’s only con-

dom factory operates in Iran.

One challenge facing the family planning pro-

gram is addressing the regional differences in con-

traceptive use. Generally, the lowest levels of

contraceptive use are seen in the least developed

provinces. Women living in Sistan–Baluchestan

PRB MENA Policy Brief 2002

5

Norplant 1%

Pills

33%

Female sterilization

31%

IUDs

15%

Condoms

10%

Injections 5%

Male sterilization 5%

Figure 4

Contraceptive Methods Used by Married

Iranian Women Who Rely on Modern

Methods, 2000

SOURCE: Iranian Ministry of Health and Medical Education et al.,

Demographic and Health Survey, Iran 2000, Preliminary Draft

(Tehran: Iranian Ministry of Health and Medical Education, 2002).

22%

10%

57%

55%

77%

67%

Urban Rural

Traditional

Modern

Figure 3

Percent of Married Iranian Women

Who Reported Using Different Types of

Contraception, by Region, 2000

SOURCE: Iranian Ministry of Health and Medical Education et al.,

Demographic and Health Survey, Iran 2000, Preliminary Draft

(Tehran: Iranian Ministry of Health and Medical Education, 2002).

province have the lowest rate of contraceptive use

(42 percent), followed by women living in

Hormozgan (55 percent). These two provinces are

among the least developed in the country. The

highest rates of contraceptive use are seen in more

developed regions: In Tehran City, 82 percent of

married women use contraceptives (see Box 3,

page 7, for more on health care in cities).

Another challenge facing the family planning

program is dealing with unplanned pregnancies.

According to the 2000 Demographic and Health

Survey (DHS), 5.2 percent of married women

ages 15 to 49 were pregnant. Of those women,

one-quarter reported that their pregnancies were

unplanned, often due to contraceptive failure. The

highest failure rates occurred with the traditional

methods (withdrawal is the main traditional

method practiced in Iran) and oral contraceptives.

The family planning program is expanding its

services to provide couples with emergency con-

traception. Abortion is illegal in Iran, except to

save the mother’s life, but postabortion care is

provided as part of primary health care.

Family Planning and Other

Development Trends

Although Iran’s Islamic government justified revi-

talizing the family planning program mainly on

macroeconomic grounds, Iranian families needed

little convincing. Iranian society is becoming

PRB MENA Policy Brief 2002

6

“Fewer children, better

education.”

“Less population, more opportunities,

prosperous future.”

“Better life with fewer children:

Girl or boy, two is enough.”

Box 2

Posters From Iran’s Family Planning Program

Iran’s family planning program uses a variety of messages to encourage couples to have smaller

families, emphasizing benefits for both individual families and society as a whole.

increasingly modern and even somewhat Western-

ized; both consumerism and media exposure are

rising. According to the 2000 DHS, 77 percent of

rural households and 94 percent of urban house-

holds had televisions, which had helped promote

the idea of a small family norm.

Improvements in female education have also

contributed to increased use of contraceptives.

The percentage of rural women who were literate

increased from 17 percent to 62 percent between

1976 and 1996; more than 75 percent of Iranian

women are literate. The rate of secondary school

enrollment has more than doubled for girls, from

36 percent in the mid-1980s to 72 percent in the

mid-1990s, while boys’ enrollments have

increased from 73 percent to 81 percent over the

same time span. In 2000, more women than men

entered universities. The longer women stay in

school, the higher the standard of living they want

for themselves and their families. The quality of

children’s lives also becomes more important.

Maternal and child health in Iran has

improved significantly. Maternal deaths due to

pregnancy and childbirth declined from 140

deaths per 100,000 live births in 1985 to 37

deaths per 100,000 live births in 1996. According

to the 2000 DHS, more than 90 percent of preg-

nant women receive at least two prenatal check-

ups, 95 percent of births are attended by a doctor

or trained midwife, and childhood vaccination is

almost universal. Between 1985 and 1996, the

mortality of children under 5 years of age dropped

from 70 deaths to 33 deaths per 1,000 live births,

and the infant mortality rate declined from 51

deaths to 26 deaths per 1,000 live births.

11

Conclusion

The Iranian experience challenges the current

assumption that demographic transition in the

Middle East and North Africa has generally been

slow. The dramatic drop in Iran’s growth rate also

raises questions as to whether the Iranian experi-

ence is unique in part because of specific charac-

teristics of Iranian society, such as the fact that the

great majority of Iranians are Shiite Muslims, who

represent a minority of Muslims worldwide.

However, the changes in Iran confirm that

committed policy and financial support, easily

available family planning services, and strong

demand can ensure that the uptake in contracep-

tive use and decline in fertility occurs very fast.

The Iranian experience highlights three key

points:

■ If family planning programs are to succeed in

Muslim countries, religion must be addressed

carefully and in a culturally sensitive manner.

PRB MENA Policy Brief 2002

7

Box 3

Women Volunteers in Cities

The health care system in rural areas of Iran is proactive in

reaching clients, but the system in urban areas often is not.

To encourage low-income residents of cities to use health

facilities, the government has developed a women’s volunteer

program. The volunteers serve as intermediaries between

families and government-sponsored health clinics. Volunteers

can also choose to participate in other areas of community

life, such as cleaning up the streets or holding classes on spe-

cial health topics.

The women’s volunteer program began in 1993 with

200 volunteers in Shahre-Rey, a low-income suburb south of

Tehran. Now there are more than 43,000 such volunteers

throughout the country, working closely with their neighbor-

hood clinics. Volunteers maintain files of demographic and

health information on each household in their area. The files

are kept at the clinic and can be used by health staff, and

volunteers use the information to help families make

appointments to address health care needs.

Urban health centers use volunteers, who are chosen in part

based on their reputation within the neighborhood, to ensure

that even low-income families receive basic health services.

FARZANEH ROUDI-FAHIMI

POPULATION REFERENCE BUREAU

1875 Connecticut Ave., NW, Suite 520, Washington, DC 20009 USA

Tel.: (202) 483-1100

■

Fax: (202) 328-3937

■

E-mail: popref

@

prb.org

Website: www.prb.org

■ Investments in health infrastructure and

human development are essential in making

family planning programs sustainable.

■ Those who assess population data can play a

key role in educating policymakers about the

likely impact of policy changes.

References

1

The Statistical Center of Iran, Iran Statistical Yearbook 1379

(March 2000–March 2001): Table 2.1.

2

United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), Country Report

on Population, Reproductive Health and Family Planning

Program in the Islamic Republic of Iran (Tehran: Family

Health Department, Undersecretary for Public Health,

Ministry of Health and Medical Education, 1988); and

Iranian Ministry of Health and Medical Education et al.,

Demographic and Health Survey, Iran 2000: Preliminary Draft

Report (Tehran: Iranian Ministry of Health and Medical

Education, 2002).

3

Amir H. Mehryar, “Repression and Revival of the Family

Planning Program and Its Impact on Fertility Levels in the

Islamic Republic of Iran,” ERF Working Paper 2022 (Cairo:

Economic Research Forum for the Arab Countries, Iran and

Turkey, 2000).

4

Farzaneh Roudi, “Iran’s Revolutionary Approach to Family

Planning,” Population Today 27, no. 7 (1999).

5

Amir H. Mehryar, “Ideological Basis of Fertility Changes in

Post-Revolutionary Iran: Shiite Teachings vs. Pragmatic

Considerations” (Tehran: Institute for Research on Planning

and Development, 2000): 18.

6

Akbar Aghajanian, “Family Planning Program in Iran,”

accessed online at http://spacer.uncfsu.edu/f_aghajanian/

papers/familyplanning.pdf, on May 7, 2002.

7

H. Moosavi, “Without Population Control We Cannot Do

Any of the Other Programs,” Iran Times, April 28, 1989.

8

Mehryar, “Ideological Basis of Fertility Changes in Post-

Revolutionary Iran”: 27.

9

M.A. Ayazi, “Islam and Family Planning” (Tehran: Daftar

Nashr Farhang Islami, 1994); and Ayalullah Muhammad

Hussein Hosseini Tehrani, “Treatise on Marriage: Population

Decline, a Heavy Blow to the Body of Muslims” (Tehran:

Hekmat Publications, 1994).

10

A Summarized Version of the First Five-Year Economic,

Social, and Cultural Development Plan of the Islamic Republic

of Iran (1989-1993), Ratified by the Islamic Consultative

Assembly on January 31, 1990 (New York: Population Policy

Data Bank, United Nations, 1990).

11

UNFPA, Country Report on Population, Reproductive Health

and Family Planning Program in the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Acknowledgments

Farzaneh (Nazy) Roudi-Fahimi of the Population

Reference Bureau prepared this policy brief with assistance

from PRB staff. Thanks are due to Amir H. Mehryar, of the

Institute for Research on Planning and Development in Iran,

for his contribution to the discussions of the policy environ-

ment; to K. Shadpoor, of the Iranian ministry of health, for

his contribution to the discussions of the status of primary

health care in Iran; and to B. Delavar, director general of the

Iranian ministry of health’s directorate of family health and

population, for his comments. Thanks are due to those who

reviewed the brief: Tom Merrick, of the World Bank; B.

Delavar; M.J. Abbasi-Shavazi, of the University of Tehran;

and Akbar Aghajanian, of Fayetteville State University.

This work has been funded by the Ford Foundation.

Design/Production: Heather Lilley, PRB

Managing Editor: Helena Mickle, PRB

© June 2002, Population Reference Bureau

PRB’s Middle East and North Africa Program

The goal of the Population Reference Bureau’s Middle East and

North Africa (MENA) Program is to respond to regional needs for

timely and objective information and analysis on population, socio-

economic, and reproductive health issues. The program raises aware-

ness of these issues among decisionmakers in the region and in the

international community, in hopes of influencing policies and

improving the lives of people living in the MENA region.

MENA program activities include producing and disseminating

both print and electronic publications on important population,

reproductive health, environment, and development topics (many

publications are translated into Arabic); working with journalists in

the MENA region to enhance their knowledge and coverage of popu-

lation and development issues; and working with researchers in the

MENA region to improve their skills in communicating their

research finding to policymakers and the media.

MENA Policy Briefs:

“Population Trends and Challenges in the Middle East and North

Africa” (October 2001)

“Iran’s Family Planning Program: Responding to a Nation’s Needs”

(June 2002)

“Finding the Balance: Water Scarcity and Population Demand in the

Middle East and North Africa” (July 2002)

These policy briefs are available on PRB’s website (www.prb.org),

and also can be ordered free of charge to audiences in the MENA

region by contacting the Population Reference Bureau via e-mail

(prborders@prb.org) or at the address below.

The Population Reference Bureau is the leader in providing timely and

objective information on U.S. and international population trends and

their implications.