A

NatioNal Family PlaNNiNg Costed imPlemeNtatioN PlaN 2015-2020

National Family Planning

Costed Implementation Plan

2015-2020

Ministry of Health and Population

Department of Health Services

Family Health Division

2015 (2072)

Government of Nepal

FP CIP

2015-2020

National Family Planning

Costed Implementation Plan

2015-2020

November 2015

Ministry of Health and Population

Department of Health Services

Family Health Division

2015 (2072)

Government of Nepal

NatioNal Family PlaNNiNg Costed imPlemeNtatioN PlaN 2015-2020

VI

VII

NatioNal Family PlaNNiNg Costed imPlemeNtatioN PlaN 2015-2020

AIDS Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome

ASFR Age-Specific Fertility Rate

BCR Benefit-Cost Ratio

CBA Cost-Benefit Analysis

CDB Curriculum Development Board

CHD Child Health Division

CIP Costed Implementation Plan

CAC Comprehensive Abortion Care

CPR Contraceptive Prevalence Rate

CSE Comprehensive Sexuality Education

CTS Clinical Training Skill

CYP Couple Years of Protection

DDA Department of Drug Administration

DFID Department for International Development

DHS Demographic and Health Survey

DHO District Health Office

DoHS Department of Health Services

DPHO District Public Health Office

EDCD Epidemiology and Disease Control Division

EDP External Development Partners

EPI Expanded Program on Immunization

FARHCS Facility-based Assessment on Reproductive Health Commodities & Services

FCHV Female Community Health Volunteers

FHD Family Health Division

FHI360 Family Health International

FP Family Planning

FPAN Family Planning Association of Nepal

FPMCH Family Planning, Maternal and Child Health

FSW Female Sex Workers

FTE Full-Time Equivalent

GDP Gross Domestic Product

GBV Gender Based Violence

GoN Government of Nepal

HA Health Assistants

HP Health Post

HIV Human Immunodeficiency Virus

HMIS Health Management Information System

HMG Health Mother Groups

HRH Human Resources for Health

ICPD International Conference on Population Development

IFPSC Integrated Family Planning Service Center

IMR Infant Mortality Rate

INGO International Non- Governmental Organisation

Ipas International Post-abortal Care Services

IUCD Intrauterine Contraceptive Device

LARC Long-Acting Reversible Contraceptive

LAM Lactational Amenorrhea Method

LMD Logistics Management Division

LMIS Logistics Management and Information System

mCPR Modern Contraceptive Prevalence Rate

MD Management Division

Abbreviations

NatioNal Family PlaNNiNg Costed imPlemeNtatioN PlaN 2015-2020

VIII

MDG Millennium Development Goal

MICS Multiple Indictor Cluster Survey

M&E Monitoring and Evaluation

MNCH Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health

MNH Maternal and Neonatal Health

MoE Ministry of Education

MoF Ministry of Finance

MoHP Ministry of Health and Population

MSI Marie Stopes International

NCASC National Centre for AIDS and STD Control

NDHS Nepal Demographic and Health Survey

NFHS Nepal Family Health Survey

NGO Non- Governmental Organisation

NGOCC Non-Governmental Organization Coordination Committee

NHEICC National Health Education, Information and Communication Centre

NHSP Nepal Health Sector Program

NHSP IP Nepal Health Sector Program Implementation Plan

NHTC National Health Training Centre

NPC National Planning Commission

NPHL National Public Health Laboratory

NPR Nepalese Rupees

NSV Non Scalpel Vasectomy

NTC National Tuberculosis Centre

OPM Oxford Policy Management

PHCC Primary HealthCare Centre

PHC/ORC Primary Health Care Outreach Clinics

PHCRD Primary Health Care Revitalization

PMTCT Prevention of Mother-To-Child Transmission of HIV

PPICD Policy, Planning and International Cooperation Division

PPIUCD Post-Partum Intrauterine Contraceptive Device

PPP Private Public Partnership

PSI Population Services International

RH Reproductive Health

RHCC Reproductive Health Coordination Committee

RHCS Reproductive Health Commodity Security

RHD Regional Health Directorate

RHSC Reproductive Health Steering Committee

RHTC Regional Health Training Center

SBCC Social and Behavioural Change Communication

SCM Supply Chain Management

SDP Service Delivery Points

SHP Sub-Health Post

SMNSC Safe-motherhood and neonatal Sub-committee

SRH Sexual and Reproductive Health

STI Sexually Transmitted Infection

STS Service Tracking Survey

TFR Total Fertility Rate

TSG Target Setting Group

TWG Technical Working Group

U5MR Under-5 Mortality Rate

UNFPA United Nations Population Fund

UNICEF UnitedNationsChildren’sFund

USAID United States Agency for International Development

USD United States Dollar

VSC Voluntary Surgical Contraception

WASH Water, Sanitation and Hygiene

WHO World Health Organization

IX

NatioNal Family PlaNNiNg Costed imPlemeNtatioN PlaN 2015-2020

Table of Contents

Introduction 1

Current Situation on Population and Family Planning 2

Population 2

Impressive but unequal progress in Family Planning 2

Unmet Need 3

Demand Satised for modern contraception 3

Contraceptive Method Mix 4

Exposure to family planning message 4

Availability of contraceptive services 4

Adolescents’ use of contraception 5

Issues and Challenges of the current Family Planning Program 6

Enhance quality FP Service Delivery 6

Capacity of service providers 8

Contraceptive commodities and logistics 9

Strengthening FP service seeking behavior 9

Advocacy for family planning 10

Management, monitoring and evaluation 10

Projecting Population Growth and Method Mix to Scale up Family Planning 11

National Costed Implementation Plan for Family Planning 12

Purpose, Vision & Goal 12

Strategic action areas and objectives 12

Strategic Action Area: Enabling Environment 14

Strategic Action Area: Demand Generation 14

Strategic Action Area: Enhancing Service Delivery 16

Strategic Action Area: Capacity Building 17

Strategic Action Area: Research and Innovation 18

Costs and Benefits of Scaling up Family Planning 19

Demographic impact 19

Health Benets 20

Social and economic benets 21

Investment requirements 22

Return on investment 23

NatioNal Family PlaNNiNg Costed imPlemeNtatioN PlaN 2015-2020

X

The way forward 24

Institutional Arrangements for Implementation 24

District-level Planning 25

Resource Mobilization 25

Monitoring and Evaluation Framework 26

References 33

List of Annexes

Annex A Estimated Total Resources Required and Disaggregated by Area 35

Annex B Estimated resource requirements of General Programme Management, by key

interventions, related programmatic activities and year, (natural units) 37

Annex C Estimated resource requirements of Enabling Environment, by key

interventions, related programmatic activities and year, (natural units) 38

Annex D Estimated resource requirements of Demand Generation, by key

interventions, related programmatic activities and year, (in natural units) 39

Annex E Estimated resource requirements of Enhancing Service Delivery, by

key interventions, related programmatic activities and year, (natural units) 42

Annex F Estimated resource requirements of Capacity Building, by key

interventions, related programmatic activities and year, (natural units) 45

Annex G Estimated resource requirements of Research & Innovation, by key

interventions, related programmatic activities and year, (natural units) 47

A n n e x H S c e n a r i o M o d e l l e d 4 9

List of Figures

Figure 1: Trends in Fertility 1

Figure 2: Trends in Contraceptive Prevalence Rate for Modern Methods 3

Figure 3: Method Mix (NMICS, 2015) 4

Figure 4: Trends in Use of Family Planning 5

Figure 5: Organogram of MoHP Health Care Delivery 7

Figure 6: Total population projections for Nepal (2011-2030) 19

Figure 7: Increase in income per capita 20

Figure 8: Maternal Mortality Rate 20

Figure 9: Cumulative cost savings 22

Figure 10: Projected expenditure under the FP Scale-up and Counter factual scenarios capita 22

Figure 11: CIP Coordination and Management Structure 25

List of Tables

Table 1: Changes in Method Mix 11

Table 2: Estimate of total resource requirements (millions) 13

Table 3: Dependency ratios 19

Table 4: Cost savings in ve sectors (millions) 21

Table 5: Cost per CYP and cost per user 22

Table 6: Investment metrics 23

XI

NatioNal Family PlaNNiNg Costed imPlemeNtatioN PlaN 2015-2020

Nepal is aspiring to graduate from a ‘Least

Developed Country’ to a ‘Developing Country’

by 2022 and is commied to improving the health

status of its people through reduction in maternal,

neonatal, infant and under-ve mortality. In the

area of Family Planning (FP), the Government

of Nepal aims to enable women and couples to

aain the desired family size and have healthy

spacing of childbirths by improving access to

rights-based FP services and reducing unmet need

for contraceptives. The Family Health Division

(FHD)/ Ministry of Health and Population

(MoHP) revised the national FP program to

devise strategies and interventions that will

enable the country to increase access to and use

of quality FP services by all—and in particular by

poor, vulnerable and marginalized populations.

Under the leadership of the MoHP a national

Costed Implementation Plan (CIP) on family

planning was developed in close consultation

with all stakeholders. The purpose of the CIP is

to articulate national priorities for family planning

and to provide guidance at national and district

levels on evidence-based programming for family

planning so as to achieve the expected results,

as well as to identify the resources needed for

CIP implementation. In addition, the CIP is

intended to serve as a reference document for

external development partners including donors

and implementing agencies to understand and

contribute to the national priorities on family

planning outlined in the Plan to ensure coherence

and harmonization of eorts in advancing family

planning in Nepal. To address the existing

challenges and opportunities for scaling up rights-

based FP in the country, the CIP focuses on ve

strategic areas. They are Enabling Environment,

Demand Generation, Service Delivery, Capacity

Building and Research & Innovation. Through

investment in these areas the country aims

to increase demand satised for modern

contraceptives from 56% (NDHS, 2011) to 62.9%

and Contraceptive Prevalence Rate (CPR) for

modern methods from 47% in 2014 (MICS) to 50%

by 2020. Likewise it aims to reduce unmet need

for FP from 25.2% in 2014 (MICS) to 22% which

would allow the country to achieve a replacement

level fertility of 2.1 births per women by 2021.

These targets may appear relatively modest but

were chosen to reect the context of a country

that has witnessed impressive gains in FP but

has CPR that has been stagnant for some time in

recent years. There are also signicant variations

in FP service use by age, geographic region,

wealth quintile and spousal separation. The target

therefore reects a FP strategy that aims to give

individual and couples a choice of contraceptive

methods with a special emphasis on reaching the

poor, vulnerable and marginalized groups. The

strategy also includes changes in the method mix

over time, with a balance between permanent,

long-acting reversible methods and short-acting

methods.

The total resources required for scaling up FP in

Nepal for the period 2015-2020 is NPR 13,765.2

million (corresponding to approximately USD

154.2 million) for six years The majority (57%)

of this total is due to the costs that are directly

incurred in delivering FP interventions. One third

(35%) is due to programme costs, or expenditures

on activities at the wider population level that

are required for FP interventions to be eectively

implemented. The remainder (8%) is indirect

costs, which predominately relate to health facility

overhead costs such as administrative sta and

utility bills. Among the programme costs the

largest planned expenditure category over the

period is Enhancing Service Delivery (1,836.9

million NPR), followed by Demand Generation

(738.4 million NPR), Capacity Building (793.8

million NPR) and Enabling Environment (679.2

million NPR). General Programme Management

Executive Summary

NatioNal Family PlaNNiNg Costed imPlemeNtatioN PlaN 2015-2020

XII

(303.1 million) and Research & Innovation (446.3

million NPR) constitute the remainder of the total

projected expenditure of 4,797.7 million NPR.

The scale up of family planning in Nepal will

contribute to further reduction in maternal

mortality rate as well as reduction in infant and

child mortality rates. It is estimated that there

will be 230 fewer maternal deaths a year and

approximately 3,000 fewer infant deaths each year

by 2030 in the FP scale-up scenario compared to

the counterfactual scenario. Likewise the number

of couple years of protection (CYPs), which is a

function of both population growth and increased

contraceptive use, is estimated at 2.9 million

by 2030 under the FP scale-up. The projected

demographic impacts of FP scale up include

a smaller increase in total population (32m by

2030 compared 33.5m under the counterfactual

scenario) and a lower (total) dependency ratio

that lead to achievement of 4.6% higher income

per capita by 2030 catalyzed by the demographic

dividend.

Slower rates of population growth translate into

cost savings to the government as there are fewer

people who need social services. A cumulative

cost savings of 46,569.9 million NPR is estimated

to be achieved over the time period (2015-2030)

under the FP scale-up scenario compared to the

counterfactual scenario in primary education, child

immunization, treatment of child pneumonia,

maternal health services and improved water

sources. Over the time period 2015-2030, for every

rupee spent on FP, Nepal is projected to save

3.1 rupees in the ve sectors mentioned above

if the FP scale-up scenario is achieved. There

are likely to be cost savings to other sectors not

included here – those related to health sector

(like improved pregnancy outcomes, reduced

unsafe abortion from unwanted pregnancies

and improved protection from HIV and other

STIs) and those outside the health sector (like

cost saving in providing social services, climate

change benets and improvements in women’s

right, empowerment and gender equality).

1

NatioNal Family PlaNNiNg Costed imPlemeNtatioN PlaN 2015-2020

The historic people’s movement in 2006

entrenched health as a fundamental human

right in Nepal (National Development Plan,

2007/2008–2010/2011), but the country has long

since recognized the benets of scaling up Family

Planning (FP). This can be seen in the prominence

given to FP services throughout the country’s

development plans and strategies, including:

the three-year Interim Development Plan,

2010/2011–2012/2013; the Eleventh Development

Plan, 2008-2013; the Second Long-Term Health

Plan, 2006-2017; the Population Perspective Plan,

2010-2031; and the Nepal Health Sector Program

Implementation Plan II, 2010-2015 (NHSP-IP II)

and NHSP III, currently being developed.

The intention behind these eorts is to develop

a well-educated, skilled and healthy nation and

graduate from a ‘Least Develo ped Country’ to

a ‘Developing Country’ by 2022. To do so it will

require not only that the economy grows by 8%

per annum, but that the growth is inclusive.

Given the level of inequality portrayed in the

recently released Nepal Human Development

Report 2014, substantial eorts are required to

reduce inequality and increase levels of human

development to sustain the peace that has only

recently been achieved. Improving health is one of

the goals with ambitious targets aimed at reducing

maternal, neonatal, and infant and under-ve

mortality as well as number of underweight

children. In the area of FP, the Government of

Nepal aims to enable women and couples to aain

the desired family size and have healthy spacing

of childbirths by improving access to rights-based

FP services and reducing unmet need for modern

contraceptives.

To expand access to quality care FP services

have been integrated into Reproductive health

package (as a basic health service package) and

provided free-of-charge to entire population in

governmental clinics. For the past thirteen years

Nepal has made remarkable progress in increasing

utilization of modern methods among currently

married women from 35% (NDHS, 2001) to

47.1 (MICS, 2014). Demand satised by modern

methods has also increased up to 63% (MICS,

2014) and unmet need for FP declined from 31%

in 1996 (NFHS) to 25.2 in 2014 (MICS).

Regardless of the overall progress in FP disparities

in FP utilization rates are still visible among

dierent sub-regions, and specic population

groups such as adolescents, poor and marginalized

women. If Nepal is to meet its domestic targets

and its international obligations—notably the

Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and

the targets of the 1994 International Conference

on Population Development (ICPD)—then the

country will need to broaden the reach and the

scope of FP services.

The Family Health Division (FHD) of the Ministry

of Health and Population (MoHP) has begun a

process of reviewing and revising the country’s

FP program to devise strategies and interventions

that will enable accelerated progress towards

ensuring increased and equitable access to and

utilization of quality FP information and services

by all—and in particular by poor, vulnerable and

marginalized populations.

Introduction

NatioNal Family PlaNNiNg Costed imPlemeNtatioN PlaN 2015-2020

2

Current situation on Population

and Family Planning

Population

The 2011 Population Census recorded the

population of Nepal at 26.5 million, with 17% of

the population living in urban areas. Population

density (average number of population per square

kilometre) has increased to 180 per km2, from 157

in 2001.

The country’s population has grown by 3.3 million

over the last decade—an annual average growth

rate of 1.35%. Over the last 40 years; however,

Nepal’s population has more than doubled,

growing rapidly between 1970 and 1980 but

slowing down in recent years. An indication

of that, is evident by the decrease of an average

household size from 5.4 (2001) to 4.9 (2011). For

the past eighteen years, the Total Fertility Rate

(TFR) gradually reduced from 4.6 (NFHS1996) to

2.3 (MICS, 2014) as it is shown in Figure 1.

The decline in fertility can be explained by several

factors such as increased age at marriage, beer

access to education among girls including in rural

areas; shi in ideal number of children among

women from 2.9 in 1996 to 2.1 in 2011 (NDHS) and

beer access to modern contraception in order to

space or limit childbearing to aain the desired

number of children.

A large proportion (37%) of the Nepalese

population is under the age of 15, although this

proportion has declined from 41% in 2006. 11% of

the population is under ve years, a decrease since

2006. Both of these are indications of a declining

trend in fertility. As is the fact, that people 65-and-

older account for 6% of the total population (up

from 4% in 2006). Examining the proportion of

children-under-ve in urban against rural areas

suggests that recent declines in fertility are more

evident in urban than rural areas and that the

transition to lower fertility began with the urban

population.

Contributing to the decline in household size is

that almost 2 million Nepalese of working age

(15-59 years) live abroad (up from 760,000 in

2001). 25% of households reported that at least one

member of their household is absent or is living

out of the country

1

, while 57% of households

reported that at least one person had migrated

away from the household at some time in the past

10 years

2

. Among the households that reported

migration of former residents, on average, about

two people migrated. It is unsurprising, therefore,

that the number of female-headed households has

increased from 15% (2001) to 23% (2006) to 26%

(2011).

Impressive but unequal progress in

Family Planning

FP has been a longstanding strategy of the

Government of Nepal in order to promote

the development of an educated and healthy

population (National Planning Commission,

2002). To achieve this, the country has set itself

ambitious goals aimed at increasing access to

voluntary FP services with a focus on poor,

vulnerable and marginalized populations.

1

Central Bureau of Statistics: Nepal Population Census 2011

2

MoHP: Nepal Demographic Health Survey, 2011

FIGURE 1:

Trends in Fertility

5

4

3

2

1

0

TFR

1996 2001 2006 2011 2014

1996 2001 2006 2011 2014

4.6

4.1

3.1

2.6

2.3

3

NatioNal Family PlaNNiNg Costed imPlemeNtatioN PlaN 2015-2020

Nepal made a signicant progress in increasing

contraceptive prevalence rate for modern

contraception among currently married women

from 35% in 2001 to 43% in 2011 (NDHS) and 47.1

in 2014 (MICS). The trends are shown in Figure 2.

Regardless of the increased use of modern

contraception, access to services is not yet universal

across the country, and mCPR varies among the sub-

regions with the highest rate at 55.1% in Far Western

Terai to 32% in Eastern Hill. Factors aecting access

to FP services are numerous including availability

and capacity of service providers; availability of

supplies; social and cultural beliefs; accessibility

of health facilities. To address low utilization of FP

services in sub-regions, a district level analysis of

service delivery and needs of communities should

be done.

Signicant inequalities in using modern

contraception still exist among poorest quintile and

highest quintile of population (35.6% vs. 48.9%).

Rural population has lower total contraceptive

rate than urban residents, however, it has higher

utilization of female and male sterilization, while

more women living in urban areas use pills,

condoms and traditional methods.

Migration complicates the interpretation of

standard FP indictors for Nepal. For example, it

is interesting to note that among married women

who live with their husbands the CPR is 55.5%.

This most likely indicates that overall CPR is

inuenced by the large number of women whose

husbands live away from home and who are

therefore not as likely to be using contraceptives.

These women may eventually need contraceptives

when their husbands return, therefore, should not

be excluded from the data on family planning,

neither from FP programmes.

Unmet Need

Unmet need measures women who do not want

any more births or those who want to postpone

the next birth at least two more years—birth

limiting and birth spacing respectively, yet are not

using a method of contraception. 25.2% of women

in Nepal (just over one-in-four) have an unmet

need for FP (MICS, 2014). While this has declined

noticeably from 31% in 1996 (NFHS) the present

level of unmet need (25.2%) is still at the same

level as it was in 2006 (25%) and provides scope

for the expansion of FP services.

Unmet need declines with age from 42% among

adolescent girls to 13% among the oldest age

group. For poorest quintile unmet need is 31%

(9% for spacing and 22% for limiting) compared

to 22% for the richest quintile (8% for spacing and

14% for limiting). Unmet need is also higher in

rural areas and is highest in the hill zone.

Migration remains a signicant factor in increasing

unmet need in Nepal, as it is for the decline in TFR.

The standard denition of unmet need counts

a woman whose husband is away from home

and who is therefore not using contraception as

having an unmet need for FP if she says that she

wants to delay or stop childbearing. In the context

of the countries such as Nepal, where spousal

separation is due to migration, it is common that

unmet need statistics are more enlightening when

disaggregated. The 2011 NDHS shows that unmet

need for women living with their husbands is

16%, while it is 58% for women whose husband

has lived elsewhere for more than a year. Clearly,

FP programs need to be tailored, recognising the

dierent contraceptive needs of these groups.

Unmet need also contributes to need for abortion.

According to NDHS (2011), 20% of the interviewed

women mentioned that the main reason for their

most recent abortion was that they did not want

any more children, while 12% said that their

husband/partner did not want the child.

contraception

Another good indicator is demand satised for

modern contraception. International evidence

suggests that for FP to achieve an impact on

population development, this indicator should be

FIGURE 2: Trends in Contraceptive Prevalence Rate

for Modern Methods

50

45

40

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

26

35

44 43

47

1996 2001 2006 2011 2014

mCPR

mCPR

NatioNal Family PlaNNiNg Costed imPlemeNtatioN PlaN 2015-2020

4

increased to at least 75%, including in rural areas

(USAID 2013).

Overall, demand satised for modern methods in

Nepal is relatively high, although there is still some

way to go in achieving the 75% target, particularly

when the indicator is disaggregated by socio-

economic characteristics and sub-regions. For

example, the lowest level of demand satised by

modern contraceptives was recorded in Western

Hill, Eastern Hill and Eastern Mountain.

The 2011 NDHS shows that demand satised for

modern methods is 56%, but with adolescent girls

(24.3%), those living in the Eastern Hills (42.7%)

and Western Hill (44.2%) and those in the lowest

wealth quintile (49.3%), have the lowest demand

satised.

Contraceptive Method Mix

The period from 1996 to 2006 saw a remarkable

increase in the use of female sterilisation, pill,

injectables and male condoms, although the use has

declined slightly in 2011 for female sterilisation and

injectables, yet has increased for male sterilisation

(Figure 4). While among the most eective methods,

Intrauterine Contraceptive Device (IUCD) and

implants continue to have a relatively low uptake

rate, although this did double between 2006 and

2011. As shown in Figure 4, the use of traditional

FP methods, although not promoted by the FP

program, also doubled over the same period (from

3.7% to 6.5%) although the NMICS in 2015 showed

a decline to 2.5% (Figure 3).

Exposure to family planning

message

According to NDHS 2011, 55% of women and 70%

of men (age 15-49) saw a FP message recently on

a poster or hoarding board, while 52% of women

and 59% of men heard FP messages broadcast

through radio. NDHS results demonstrate that:

exposure to FP messages is lower in rural areas

than in urban and older age categories of women

are exposed less to FP messages. This is an

important nding since mothers and mothers-in-

law can be a vital source of information on FP for

young girls.

Availability of contraceptive services

The Family Health Division of the MoHP has

noted the rapid expansion of the private sector

and has commied to encourage the private sector

and non-governmental organisations to play an

expanded role in the national FP programme

(NHSP-IP II).

Currently, short-acting FP methods (male

condoms, pill, and injectables) are provided on

a regular basis through all governmental health

posts, sub health posts, Primary health Care

Outreach Clinics (PHC-ORC), periphery level

health workers and volunteers (Condoms and

resupply of pills). Services such as IUCD and

Implants are available only at limited number of

Primary Health Care Centres (PHCC) and health

posts where trained personnel are available.

Depending on the district, sterilization services

are provided at static sites or through scheduled

“seasonal” or mobile outreach services. Almost

all district Family Planning, Maternal and Child

Health (FPMCH) clinics are providing all types

of temporary FP methods regularly. FP services

are also providing by INGOs (International

Non- Governmental Organisations), NGOs (Non-

Governmental Organisation), private service

providers and social marketing system.

Sixty-nine percent (69%) of the population accesses

their modern contraceptive method from the

government sector, however this is a signicant

decline from the 77% recorded in the 2006 NDHS

and does vary by method choice. Because method

choice depends on the level of health facility, it

denes where women go to obtain a preferred

FIGURE 3: Method Mix (NMICS, 2015)

Traditional

5%

Female

Sterilization

36%

Male

Sterilization

10%

IUCD

3%

Implant

3%

Injectables

26%

Pills

26%

Condoms

26%

5

NatioNal Family PlaNNiNg Costed imPlemeNtatioN PlaN 2015-2020

method. A risk is a limitation of choices if a woman

hasn’t received full information about all methods

at the point of entry.

9% of users obtain their methods from the NGO

sector, mostly from Marie Stopes International

(6%) and the Family Planning Association of Nepal

(2%). It is the commercial private sector that has

seen the most marked increase, however—rising

from just 14% in 2006 to 22% in 2011. Of particular

note is the use of pharmacies for the short-term

methods, with 32% of pill users, 12% of injectable

users and 52% of condom users obtaining

their methods from this source. Private sector

pharmacies are widespread in Nepal and provide

diagnosis and treatment including prescription of

drugs. They are a major recipient of out-of-pocket

spending by all income groups, although they are

predominantly based in urban areas.

If FP is to reach those who are currently

underserved or population groups that are not

being adequately reached by current approaches,

then the FP programme will need to make the best

use of all resources available. This will require that

considerable eort be devoted to strengthening

partnerships with the private and NGO sectors

3

.

Adolescents’ use of contraception

Adolescents and youth account for one-third of

Nepal’s population. Early marriage and early

childbearing continue to be the norm in Nepal,

although the median age at rst marriage has

increased over the years. Adolescent childbearing

is still common, although decreasing – adolescent

birth rate is 81 per 1000 women (MICS 2014 – 71).

Among adolescents and youth, contraceptive

use can prevent unintended pregnancy and

early childbearing and their consequences. In

Nepal knowledge about FP is almost universal

(99.9 percent) including among adolescents

and youth. However, only 14percent of married

adolescent girls age 15-19 and 24 percent of

married women age 20-24 are currently using a

modern contraceptive method. Unmet need for

FP has been estimated to be highest (42 percent)

for married girls age 15-19, followed by 37 percent

among married women age 20-24 (MoHP et al.,

2012). The data on contraceptive use and unmet

need among young people is unavailable in

Nepal. According to Demographic and Health

Surveys (DHS) comparative report on adolescent

sexual and reproductive health around the world,

unmarried young women are more likely to use

modern contraceptive methods and also to have

higher levels of unmet need for FP than currently

married young women (Khan and Mishra, 2008).

FIGURE 4: Trends in Use of Family Planning

50

45

40

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

Any modern method Female Sterilisation

Method type

Percent of married women

currently using a method of FP

Male Sterilisation Any traditional method

1996 NHFS 2001 NDHS 2006 NDHS 2011 NDHS

3

NHSP-IP II – Mid-Term Review Report (2013)

NatioNal Family PlaNNiNg Costed imPlemeNtatioN PlaN 2015-2020

6

Issues and Challenges of

the current Family Planning

Program

For eective scale-up of the FP program in

Nepal, a number of challenges and issues must

be addressed by 2021. Five program areas or

components are essential for implementing

a successful FP program: strong advocacy to

increase visibility and support for the program,

behavior change communication interventions to

address the knowledge-use gap among FP clients;

strong management to ensure ecient and

eective program implementation; availability of

broader range of contraceptive commodities at

all levels of service delivery; sucient numbers

of skilled health providers to provide FP services

eectively and appropriately equipped facilities

to provide quality FP services.

Enhance Quality Family Planning

Service Delivery

Access to high-quality FP services is a human right

and should be provided without discrimination

and coercion.

Family planning information and services are

provided through government, social marketing,

non-governmental organizations and private

sectors. In government health system, currently,

short-acting FP methods (male condoms, pill, and

injectables) are provided on a regular basis through

all levels of health facilities including health posts,

sub health posts, PHC- Outreach clinics. Female

Community Health Volunteers (FCHVs) provide

information to community people, and distribute

Condom and resupply pills. Services such as

IUCD and Implants are available only at limited

number of PHCCs and Health Posts (HPs) where

trained personnel are available. Depending on the

district, sterilization services are provided at static

sites or through scheduled “seasonal” or mobile

outreach services. Almost all district hospitals are

providing all types of temporary and permanent

FP methods regularly. Therefore, at central,

regional and district level women can access

all the 7 methods of FP while at primary health

care accessibility to a full range of FP services is

limited. Family Planning services are integrated at

all levels of MoHP health care delivery, as shown

in Figure 5.

Due to integrated nature of FP services, women

should be able to access the services at any

service delivery point and in any geographical

district. However, “supply” and “demand”

related challenges aecting the access still exist

in the country. For example, shortage of human

resources for health overall and in particular lack

of skilled service providers, lack of supplies and

contraceptives especially at primary health care

level aect accessibility and quality of contraceptive

services. Women experience challenges to access

the services due to travel 2014 arrangements such

as nding a means of transportation, time spent on

travel, costs of travel; and sometimes due to costs

of services (STS, 2013). In some cases, gender and

culture related norms aect the access, for example

in some cases women needed to get a permission

from husband/other members of family to go to a

health facility for healthcare services, including FP .

(STS, 2013)

To reduce access barriers the Government of Nepal

(GoN) provides free counseling and services

including contraceptives of choice, in addition

to a nominal wage compensation for clients

undergoing Voluntary Surgical Contraception

(VSC) and covers costs of services included in

the essential health package. However, due to a

lack of awareness about these entitlements, some

groups of population have not used the incentives

7

NatioNal Family PlaNNiNg Costed imPlemeNtatioN PlaN 2015-2020

FIGURE 5: Organogram of MoHP Health Care Delivery

4

and continue paying out of pocket. Interventions

on increasing awareness of clients and service

providers about entitlements for free care at all

levels of public-sector health care institutions

should be delivered at communities.

By 2015 MoHP aimed to provide all 5 types of

temporary FP methods at 60% of health post

(NHSP IP – II). Likewise the government also

planned to have regular VSC services available at

all district hospitals and selected PHCCs. However

only 18% of Health Posts were able to oer all

ve methods of FP in 2013 (STS) and this gure

increased to only 20% in 2014 (UNFPA, 2014). The

urban-rural disparity in access to services is also

huge, compared to 82.5% of health facilities in the

urban areas only 22.8% of health facilities in the

rural areas are currently oering all ve methods

of temporary contraceptive methods (UNFPA,

2014).

4

Annual Report, DoHS

MINISTRY OF HEALTH AND POPULATION

DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH SERVICES

MD

CHD

FHD

LMD

EDCD

PHCRD

NTC

NHTC

NPHL

NCSAC

NHEICC

DIVISION CENTER

CENTRAL HOSPITALS-8

REGIONAL HEALTH DIRECTORATE-5

SUB-REGIONAL

HOSPITAL-2

REGIONAL

TRAINING CENTER-5

REGIONAL

MEDICAL STORE-5

REGIONAL

TB CENTER-1

ZONAL HOSPITAL-10

DISTRICT PUBLIC HEALTH

OFFICE-16

DISTRICT/OTHER

HOSPITALS-72

DISTRICT HEALTH

OFFICE-59

PRIMARY HEALTH CARE CENTER/

HEALTH CENTER-207

HEALTH POST-1,689

SUB-HEALTH POST-22127

FCHV

50,007

PHC/ORC CLINIC

12,608

EPR OUTREACH CLINIC

16,746

REGIONAL

HOSPITAL-3

NatioNal Family PlaNNiNg Costed imPlemeNtatioN PlaN 2015-2020

8

To facilitate access to FP services, the GoN

supported integration of FP in post-partum,

post-abortion services, immunization program

and promoted expansion of service sites oering

long acting methods. At least ve methods of

contraception were available in 91.4% of health

facilities providing safe abortion services (STS,

2013) while only 30% of women accepted any one

method of contraception aer an abortion (HMIS,

2013). Lack of proper counseling on FP during post-

partum and post abortion visits contributed to

low uptake of modern contraceptives. According

to NDHS, 91% of post-partum women and 56 %

of women who had abortion were not provided

counseling on family planning. Although causes

of low contraceptive use among women in post-

abortion and post-partum period need to be

analyzed further, one obvious reason is poor

quality of counseling on family planning. Poor

quality of counseling is an issue for private and

NGO sectors as well as demonstrated by NDHS

(2011).

Quality of service plays key role in accepting,

rejecting and discontinuation of FP services.

Overall, 51 percent of contraceptive users

discontinued using a method within 12 months

of starting its use (NDHS, 2011). Twenty-six

percent of episodes of discontinuation occurred

because the women’s husbands were away,

12 percent was due to the fear of side eects or

health concerns, and 5 percent because the woman

wanted to become pregnant. The most common

discontinued modern method was oral pills. Fear

of side-eects and health concerns can be reduced

through quality counseling that would also enable

a couple or a woman to make informed choice

of contraception. However, only 63% of women

using contraception received full information

on possible side-eects and 59% of them were

informed on what to do if they experience side

eects. Percentage of those who were informed

about side eects was the lowest among women

who chose oral pills and female sterilization.

MoHP/FHD has invested in improving quality

of care through various interventions such as

establishing competency based training, and

training on infection prevention, conducting

comprehensive FP training for all level of service

providers and establishing/strengthening FP

service center. However, these eorts require

a long-term support including investments to

have sustainable results. A systematic approach

for improvement of quality of care including

systematic review and update of clinical protocols

and guidelines at national and clinic level,

developing indicators on quality assurance,

monitoring compliance with standards and

clinical audit for solving problems through a team

approach are needed to be in place. Education of

communities about clients’ rights and solicitation

of clients’ feedback on a regular basis need to be

embedded in quality improvement process.

Capacity of service providers

Trained, competent and condent human

resource is vital for providing integrated quality

FP services. The GoN has started implementation

of the Human Resource for Health -Strategic

Plan (2011-2015) to address challenges and

constraints related to distribution of skilled

human resources for health. However, health

facilitates at districts and primary health levels

still experience signicant shortage of health

providers, particularly obstetrician/gynecologists

and nurses (STS, 2013). The lack of skilled health

providers, especially female health professionals,

inhibits access and use of family planning. (PEER

study, 2012). Existing challenges with lack of

long-acting reversible methods or interruptions

in supply in most sites are mainly due to lack

of trained health providers (STS 2013). In some

cases, misconceptions and negative perceptions

harbored by healthcare providers themselves

limits individuals’ access to FP services of their

choices. In order to increase understanding of

health managers and services providers about the

role of FP for improving women’s health especially

within the integrated service delivery modality

and strengthen skills of service providers, support

for continuous capacity building is vital.

Family Planning training is institutionalized in

the country and delivered through a nationwide

network of training health sites under the

National Health Training Center (NHTC). The

national training plan, developed in co-ordination

with the Family Health Division, needs to be

timely implemented. A challenge is insucient

pool of trainers and coverage of service providers

including those from private sector. There is also

9

NatioNal Family PlaNNiNg Costed imPlemeNtatioN PlaN 2015-2020

a need to institutionalize certain training like

postpartum FP counseling and postpartum IUCD

and to establish an integrated mechanism for post-

training follow-up and supportive supervision.

Another key area is to update training curricula

and make it available as e-learning modular

course to reduce o-site training duration and

thus absenteeism from work, in addition to

covering more service providers.

Contraceptive commodities and

logistics

In Nepal Government procures most of the FP

commodities required for public sector and

oen for NGOs. In 1993 MoHP established

Logistics Management Division (LMD) to manage

procurement and logistics management of all

health commodities including contraceptives.

Under the leadership of LMD national capacity

on forecast, purchase and distribution of

commodities has been signicantly improved in

the country. According to the FARHCS (UNFPA,

2014), “no stock out” of male condoms, oral pills

and injectable was reported in 100% PHCCs

and SHP; and 99% of hospitals and 99% HPs. In

addition 80% of PHCCs and 72% of HP had no

stock out of IUCD and implants.

Recognizing an increased demand for long-acting

methods, MoHP/FHD has aimed to increase

access to these methods in all health posts and

primary health care centers by end of NHSP II

(2015). However, the services are available only

in limited sites due to lack of supplies and skilled

personnel.

Factors contributing to stock outs of contraceptives

at all levels of service delivery include long

bureaucratic policies and procedures to purchase

commodities. Likewise supply of commodities

from regional stores to district and from district

stores to health facility level is oen interrupted.

In cases when facilities have stock outs of IUCD

and implants, it is mainly due to lack of trained

health sta to provide services and as a result no

request for the commodities

Strengthening FP service seeking

behavior

Knowledge of contraceptive methods is an

important factor for increasing uptake of FP

services. Radio, television and posters are three

main channels for FP messages that the majority

of the population has been exposed to. Modern

methods are more widely known than traditional

method. Although most people have heard about

at least one modern method of contraception

(NDHS, 2011), this does not represent existence,

among the entire population, of knowledge that

is comprehensive enough to allow individuals

and couples to choose and use FP services.

This is demonstrated by However, uptake of

modern contraceptives is hindered by existing

misconceptions, myths and fear of side eects.

Culture and religious ties such as a strong son

preference, religious beliefs and concerns about

side-eects (PEER Study 2012) also serve as

substantial barriers to increasing the Modern

Contraceptive Prevalence Rate (mCPR).

Regardless of almost universal knowledge about

contraception, married adolescents (15-19 years

old) has the lowest demand satised by modern

methods among all age groups (24.3), while their

unmet need for spacing is the highest (37.5).

Married women whose husbands are away

discontinue using contraception but in many cases

fail to use FP when reunite with spouses.

Men play a signicant role in decision making

on family planning. Engagement and education

of men about FP is crucial for reducing unmet

need for family planning, especially for modern

methods. Myths about contraception still exist

among men. For example, about 20 percent of men

think that women who use contraception may

become promiscuous. Men living in rural areas,

the Terai, and the Western region, particularly the

Western hill sub-region, are more likely to have

these perceptions than other men. Men with SLC

and higher level of education and those in the

highest wealth quintile are less likely to have these

misconceptions regarding contraceptive use than

other men.

Targeted communication and behavior change

approaches are needed to address the existing

challenges especially among adolescents

and migrants’ population. Increasing men

involvement in FP will benet elimination of

myths and encouragement of service seeking

behavior among women. Likewise demand and

NatioNal Family PlaNNiNg Costed imPlemeNtatioN PlaN 2015-2020

10

utilization of FP services among special groups like

postpartum mothers, Muslims and disadvantaged

groups also need to be improved through targeted

interventions.

Advocacy for family planning

While the overall policy environment for FP is

positive, including the incorporation of FP/RH

into the GoN’s development and national health

programmes, the government’s strong policy and

strategy commitments have not been accompanied

by an equally commensurate dedication of

national nancial resources to meet the full

need for FP program and contraceptives. Some

decision makers, managers and service providers

are of view that FP is a mature program in Nepal

and hence does not need as much aention as

new programs require. Such perception has to

some extent negatively inuenced nancial and

programmatic commitments to FP. In addition,

advancing FP requires a multi-sectoral approach

which means that engagement of other sectors

such as education, youth, nance, women

and social welfare, transportation needs to be

strengthened.

Another aspect of creating enabling environment

for FP is to ensure that policies and legislations

are in place to facilitate access to services for most

vulnerable populations such as adolescents and

young people, women from poor selements

(urban or rural) and ethnic minorities. Although

the GoN has in place policies and regulations

related to safe motherhood, SRH and FP services,

a regular update and communication of such

policies to all relevant stakeholders, duty bearers

and right-holders alike is needed to scale up FP.

Gender equality and cultural factors play a

signicant role in making decisions on uptake

of contraceptives among women and especially

girls. Advocacy interventions need to be in place

to address men engagement in family planning,

role of religious leaders and other community-

gatekeepers.

Management, monitoring and

evaluation

Clear leadership responsibility and authority are

essential for scaling up FP in the multi-sectoral

environment. Current bolenecks in supervision,

monitoring, and evaluation include limited

dedicated stang resources at the national and

district levels as well as insucient capacity

to utilize available data and implement current

guidelines and other tools. A need for strengthened

co-ordination at central, regional and districts

levels both within the government system as well

as with external development partners cannot be

over-emphasized.

11

NatioNal Family PlaNNiNg Costed imPlemeNtatioN PlaN 2015-2020

Projecting Population Growth

and Method Mix to Scale up

Family Planning

To scale up FP in Nepal, demand satised for

modern contraceptives is modelled to reach 62.9%,

which reects on Contraceptive Prevalence Rate

(CPR) and unmet need. CPR for modern methods

will reach 50% and unmet need will be reduced

to 22 % by 2021. At this rate of contraceptive

use, TFR will be at 2.1 births per women, which

represent replacement level.

This target may appear relatively modest but was

chosen to reect the context of Nepal: a country

that has made impressive gains in FP, but which has

experienced a stalling CPR more recently, as well

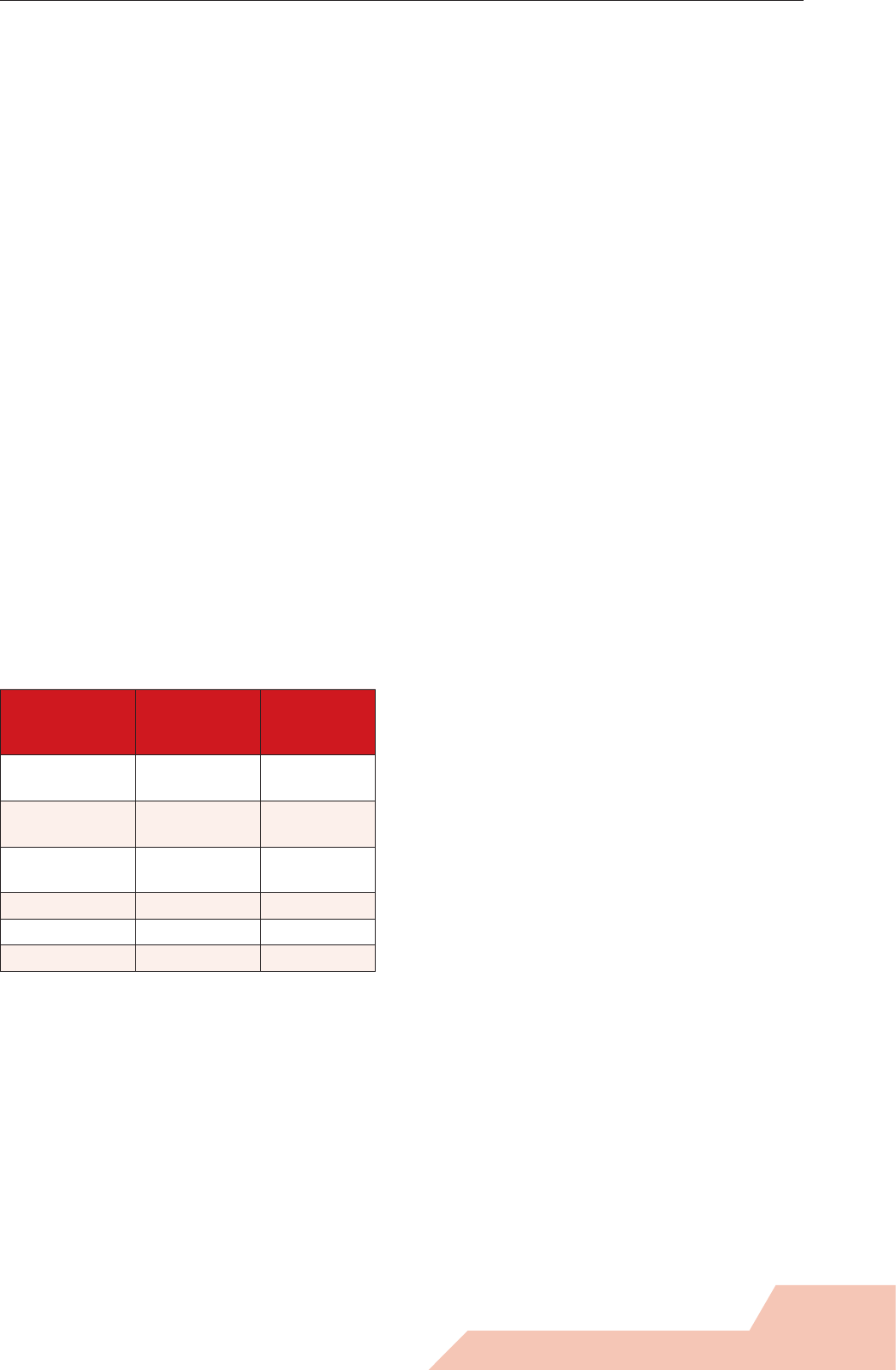

as signicant variations in use by age, geographic

region, wealth quintile and spousal separation.

The target therefore reects a FP strategy that aims

to give women a choice in contraceptive method

and to reach poor, vulnerable and marginalised

groups. The strategy is also to make changes in

the method mix over time, with a balance between

permanent, long-acting reversible methods and

short-acting methods. Previous analysis by the

Nepal expert working group served as the basis

for these changes, which reect historical trends,

shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Changes in Method Mix

2015 2020 2025 2030

Pill 8.3% 8.3% 8.3%

8.3%

Condom 8.9% 9.1% 9.3%

9.5%

Injectable 18.7% 18.9% 19.1%

19.3%

IUD 3.1% 3.7% 4.4%

5.0%

Implant 3.2% 4.2% 5.2%

6.2%

Male sterilisation 15.7% 15.7% 15.7%

15.7%

Female sterilisation 29.1% 27.0% 25.0%

22.9%

Traditional 13.1% 13.1% 13.1%

13.1%

Total 100.0% 100.0% 100.0%

100.0%

Source: OPM calculations based on Nepal working group projections and NDHS 2011.

NatioNal Family PlaNNiNg Costed imPlemeNtatioN PlaN 2015-2020

12

National Costed

Implementation Plan

for Family Planning

Purpose

Recognizing the need to revive and scale up FP

in Nepal, the Government has developed the

Costed Implementation Plan (CIP) on FP. The

development of the plan has been guided by the

strategic directions developed through extensive

consultations with relevant stakeholders at

national, regional and district levels and is in line

with the National Health Sector Program (NHSP

III 2015-2020) which is currently being nalized. As

did the previous health sector plans (NHSP I and

II) the upcoming NHSP III has also recognized FP

as a priority, and it is considered as a component

of reproductive health package and essential health

care services.

The purpose of the CIP is to strengthen the

foundation for FP programming and service

delivery at national and districts levels as well as

to identify the activities to be implemented and

resources needed for achieving the results.

The CIP clearly denes priorities for strategic

actions, delineates the activities and inputs needed

to achieve them, and estimates the costs associated

with each as a basis for budgeting and mobilizing

resources required for implementation at dierent

levels by organizations and institutions over the

2015-2020 period. In addition, CIP is intended to

serve as a guide for development partners and

implementing agencies on areas of need to ensure

the success of the national FP program.

More specically, it will be used to:

l Inform policy dialogue, planning and

budgeting to strengthen FP as a priority area

l Prioritize strategies on FP to be adopted over

the next 6 years.

l Enable FHD, NHTC, LMD and NHEICC

to develop their respective implementation

plans with eective, ecient and actionable

interventions/activities and timelines

identied.

l Support Government and national partners

to understand nancial and technical support

needs for scaling up FP in the country.

l Support advocacy eorts for FP with clear

messages on impact of FP on health & non-

health sectors including cost-savings to justify

investments.

l Set benchmarks that can be used by the MoHP

and external development partners to monitor

and support the national FP programme.

Vision

Healthy, happy and prosperous individuals and

families through fulllment of their reproductive

and sexual rights and needs

Goal:

Women and girls - in particular those that are

poor, vulnerable and marginalised – exercise

informed choice to access and use voluntary FP

(through increased and equitable access to quality

FP information and services).

Strategic action areas and objectives

The strategic objectives reect the issues and

challenges in FP that have to be addressed in

order to scale up FP interventions in the country

to reach the goal. The strategic objectives of the

CIP ensure that limited available resources are

directed to areas that have the highest need to

reduce the unmet need for FP in Nepal. In the case

of a funding gap between resources required and

13

NatioNal Family PlaNNiNg Costed imPlemeNtatioN PlaN 2015-2020

those available, most eective activities should

be prioritize to ensure the greatest impact and

progress towards the objectives laid out.

Strategic Action Area and Objectives:

The Costed Implementation Plan on FP has ve

strategic areas for action to achieve its objectives

in order to scale up FP in the country with a focus

on rights of women and girls.

l Enabling Environment: Strengthen enabling

environment for family planning

l Demand Generation: Increase health care

seeking behavior among population with

high unmet need for modern contraception

l Service Delivery: Enhance FP service delivery

including commodities to respond to the needs

of marginalized, rural residents, migrants,

adolescents and other special groups.

l Capacity Building: Strengthen capacity of

service providers to expand FP service

delivery network

l Research and Innovation: Strengthen evidence

base for eective programme implementation

through research and innovations

General Programme Management:

Programme Management is an essential component

of managing and overseeing the implementation

of activities that the accelerated scale-up plan

envisages. In short, programme management is

critical for ‘pulling everything together’ and to make

sure that each component of the programmatic

interventions is working as it should and is aligned

and coordinated with the full range of interventions.

General Programme Management covers the

full costs of the government personnel required

to implement programmatic activities, at the

Central Level (FHD) and District/ Regional

Level. The resource requirements / costs that are

involved estimate the number of stas by cadre

for whom FP activities constitute a signicant

share of their daily work and then combine

this with information on the share of their time

allocated to FP and information on salaries /

allowances. Estimated resources required for

general programme management to implement

the Costed Implementation Plan are shown in

Annex B.

Each Strategic Action Area and General

Programme Management has a set of costed

activities. The activities were generated, under

the leadership of FHD, through Key Informant

Interviews and several rounds of consultations

at central, regional and district levels involving

a wide range of stakeholders in the government,

donor communities, civil societies, professional

organizations, social marketing and private

sector. Cost estimation of the activities including

commodities was done by an expert group

including the Technical Working Group (TWG)

member. The estimated costs that emerged were

then reviewed by Oxford Policy Management

(OPM) and technical experts at UNFPA

Headquarter. This review involved ensuring that

the strategic interventions planned are in line with

global recommendations and best practices. OPM

also checked for and corrected calculation errors;

Scaling down observed over-estimates for certain

Table 2: Estimate of total resource requirements (millions)

2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 Total

NPR

Total

USD

Direct intervention

costs

1,229.6 1,258.9 1,289.3 1,336.1 1,365.8 1,363.6 7,843.3 87.9

57%

Programme costs 1,099.3 1,094.5 860.6 780.4 456.2 506.8 4,797.7 53.8

35%

Indirect costs 172.7 178.6 184.4 190.3 196.3 201.9 1,124.1 12.6

8%

Total 2,501.6 2,531.9 2,334.3 2,306.8 2,018.4 2,072.2 13,765.2 154.2

Year as % of total cost 18% 18% 17% 17% 15% 15% 100%

Source: Multi-Year Costed Implementation Plan, OneHealth modeling and OPM calculations

NatioNal Family PlaNNiNg Costed imPlemeNtatioN PlaN 2015-2020

14

activities; and Removing medical equipment and

facility rehabilitation costs in order to eliminate

double-counting.

As shown in Table 2 the total resources required

for scaling up FP in Nepal are $ 154.2 million for

six years that include:

1. Direct intervention costs - commodities and

supplies and medical personnel (constituting

57% of the total cost).

2. Programme resources – activities at the wider

population level that are required for an

intervention to be implemented eectively

(constituting 35% of the total cost).

3. Indirect costs – costs related to health facility

overhead costs such as administrative sta

and utilities bills (constituting 8% of the total

cost).

Estimates for all required resources are presented

in the Annexes.

Strategic Action Area: Enabling

Environment

A policy environment that enables the above

four Action Areas to be implemented eectively

is key for a successful FP programme. Strategic

interventions in this area include increasing

advocacy at all levels for FP; addressing legal

and socio-cultural barriers to young people

accessing FP; strengthening the integration of

services; and developing /updating national

polices and strategies to facilitate task shiing.

Estimated resources required to implement the

key interventions are presented in Annex C.

KEY INTERVENTIONS:

l Increase Advocacy for Family Planning.

Identify national champions for FP from

multiple elds and support them to advocate

for FP by providing advocacy materials/tools

and conducting follow up meetings. Develop

and distribute advocacy packages using global

evidences and tools, including modeling

exercises, (in English and Nepali) for key

stakeholders. Support high level advocacy

events at central level and districts engaging

parliamentarians, governmental ocials and

donors as well as civil society organizations

and media. Support advocacy events at

community level including celebration of FP

day at community level

l Address legal and socio-cultural barriers to

access to FP services for young people and

other special groups. Update the National

ASRH strategy & review implementation

of the strategy in 2019. Advocate with

Ministry of Education (MoE), Curriculum

Development Board (CDB) and key

stakeholders to incorporate Comprehensive

Sexuality Education (CSE) components in

curriculum for Grade 9-10. Develop a national

strategy on increasing access to voluntary FP

services among disabled people and support

its implementation ensuring multi-sectoral

co-ordination and collaboration.

l Advocate for integration of FP services.

Support development of national FP service

integration strategy as part of the CIP for FP

and NHSP III. Based on the strategy, develop

operational guidelines and disseminate them

at all levels of service delivery.

l Promoting task shiing and sharing. Develop

a national strategy on task shiing/sharing.

Strategic Action Area: Demand

Generation

The variation in the unmet need for FP in Nepal

is an indication of signicant scope for increasing

access to FP, although it is also an indication that

demand for FP services is not uniform and that

promoting such access will require specic and

targeted eorts. Demand generation strategy will

focus on strengthening health service seeking

behavior especially among adolescents and young

people and marginalized populations.

Demand generation eorts will focus on targeted

approaches to reach adolescents in and out of

schools especially in urban areas; reduce fear

of side eects of modern contraception as well

as myths and misconceptions among women

and men; strengthen community based work to

provide full information on FP to marginalized

population and use innovative nancing to reduce

nancial barriers to the services. Estimated cost

of key interventions for Demand Generation is

presented in Annex D.

15

NatioNal Family PlaNNiNg Costed imPlemeNtatioN PlaN 2015-2020

KEY INTERVENTIONS:

l Support integration and implementation

of Comprehensive Sexuality Education

(CSE) in schools secondary and higher level.

Support will be provided to fully implement

CSE curriculum in grades 6-10 and interactive

sessions with students in grades 11-12 will be

conducted. It will include advocacy with the

Ministry of Education, training of educators/

teachers and updating teaching materials and

other communication tools.

l Reach adolescents with FP messages using

innovative approaches. Support promotion

of FP among adolescents and young people

using SMS and mobile technology. Mobile

application on FP and health related issues

will be developed and introduced in

collaboration with phone companies with

a focus on adolescents and young people

needs. In addition a telephone hotline will be

set up to provide information on emergency

contraception and other SRH/FP related

issues to young people. A program on access

and use of contraceptives for adolescents

living in urban areas will be supported for six

years.

l Design, implement and evaluate special

programme to increase access and utilization

of FP among adolescents and young people. To

support access to contraceptives information

and services among adolescents and young

people, a peer education programme will be

developed and implemented both in- and

out-of school. Strengthen program design,

implementation and evaluation for Social

and behavior change communication, that

includes development of FP communication

strategy, development of IEC materials and

media messages, evaluation of FP Social and

Behavioural Change Communication (SBCC),

development of communication tools package

focused on the targeted groups and building

capacity of partners working in SBCC. Ensure

that BCC interventions address needs of

newly married young people to delay rst

pregnancy.

l Increase knowledge about FP among

individuals/couples to facilitate decision –

making on contraceptive use. BCC materials

will be developed to target specic groups

of population with higher unmet need

for modern FP methods. Communication

campaigns will be supported in 2015 and

2018.

l Reduce socio-cultural barriers to access

FP services. Support community-

based programmes on FP to strengthen

communication skills and capacity on FP

among FCHV and health workers.

l Reduce fear of side eects, myths and

misconceptions about FP through

various communication channels. Support

development of IEC materials that

emphasize value of daughters and clarify

information about modern contraceptives

to be used by FCHVs, health workers and

community leaders. Organize forums and

interactive sessions on clients’ satisfaction in

communities’.

l Develop and implement micro-plans for

specic groups. Districts’ micro-plans will

be developed based on existing evidence on

barriers to FP utilization among underserved

groups of population.

l Develop and implement a programme

focused on needs for FP among migrants

and their spouses. The programme will

provide information and services to returning

migrants and their spouses to prevent

unintended pregnancy. In addition integrated

information on preventing STIs/HIV and

unintended pregnancy will be provided to

migrants prior to their departure.

l Develop and implement FP programme

targeting hard-to-reach people. The program

will use national guidelines for reaching the

unreached population during development

of targeted programmes. This would include

a mapping exercise to identify communities

with high unmet need for FP followed by

designing of targeted approaches to reach out

to marginalized population with information

and counseling on FP through existing

mechanisms including community mobilizers.

The programme will be implemented in urban

slums as well as in rural areas. Total Market

Approach will be introduced to ensure that

underserved target populations have access

NatioNal Family PlaNNiNg Costed imPlemeNtatioN PlaN 2015-2020

16

to contraceptives. A market segmentation

action plan will be developed.

l Provide information on FP to women in

post-partum and post-abortion period.

Support and strengthen group counseling

and provision of contraceptive information

for couples and women visiting Expanded

Program on Immunization (EPI) clinics

during vaccination days as well as promoted

counseling among women in postpartum

period in Health Mother Groups (HMGs).

Incorporate information on FP into

Comprehensive Abortion Care (CAC)

services.

Strategic Action Area: Enhancing

Quality Service Delivery

The key interventions are designed to increase

access to services, particularly for vulnerable

as well as hard to reach populations, and to

increase the quality of services being provided.

Such activities range from supporting NGOs

who are providing FP services to strengthening

coordination with the private sector to improve

access and quality of services. Among government

services activities designed to enhance service delivery

include improving services across all levels (FCHV/

Community Level; PHC/ORC clinics; SHP/HP/

PHCs, including birthing centres; District Zonal &

Regional and central level Hospitals) and enhancing

coordination at the central and district levels. It is

also designed to improve facility recording and

reporting, to strengthen the management capacity

of FP ocers and to establish a dedicated Quality

of Care unit. Additional activities will include

supporting Medical College Teaching Hospitals,

eorts to ensure contraceptive security and support

to strengthening social marketing and private

sector role.

Beer quality FP, greater coordination of FP

services, and an integration of the FP services

across government, NGO and private providers

combined with improvements in management

and quality assurance will go a long way to

enhancing the supply side of service delivery, thus

stimulate demand for and increasing the uptake

of FP services. Estimated resources required to

implement the key interventions are presented in

Annex E.

KEY INTERVENTIONS

l Improve FP integrated services at FCHV/

Community Level. Update FP orientation

package including post-partum FP for FCHVs

and conduct refresher training for FHCVs

using the updated FP training package. In

addition build capacity of FCHVs in conducting

pregnancy test, counseling on family planning,

antenatal care and post-abortion care. To

increase access to condoms, especially among

youth, support establishment of condom

boxes at appropriate places in community.

Mobilize and provide support to expand

access to long-acting reversible contraceptives

through satellite clinics and comprehensive

FP camps. Support South-South Cooperation

by organizing study-visits to countries with

successful and eective community based

programme son FP(e.g. Bangladesh, Indonesia)

l Improve services at PHC/ORC clinics.

Conduct rapid assessment of PHC/ORC

situation and develop 1-2 model PHC/ORCs

per VDC (high unmet need districts), later

to be static Service Delivery Points (SDP).

Strengthen capacity of urban health clinics to

deliver FP services (20 municipalities).

l Improve services at HP/PHCs, including

birthing centers. Support health facilities

with commodities (long-acting ad short-

acting methods) and ensure that communities

are properly informed about available services

though appropriate communication channels.

Launch a pilot programme on expanding use

of Post-Partum Intrauterine Contraceptive

Device (PPIUCD) in birthing centers. Promote

task-shiing to expand services especially in

districts with high unmet need.

l Improve services in District Hospitals.

Expand availability of all short and long-acting

reversible methods and one VSC method

by supporting procurement and supply of

contraceptives to district hospitals, conducing

capacity building events for health providers

and strengthening supportive supervision.

Develop the 24 Integrated Family Planning

Service Centers (IFPSCs) as comprehensive RH

clinics. Support development of district-level

FP micro-planning & commodity forecasting

including situation analysis and training.

17

NatioNal Family PlaNNiNg Costed imPlemeNtatioN PlaN 2015-2020

l Improve services in Zonal and Regional

Hospitals. Strengthen integrated FP services

in multi-disciplinary hospitals by conducting

training, ensuring supportive supervision

and introducing clinical guidelines/protocols

on FP service provision. Expand training on

recanalization.

l Social marketing. Revive private provider’s

network and implemented interventions

through Private Public Partnership (PPP)

models for strengthening supply chain

commodity management.

l Support NGOs providing FP services. Revive

work of Non-Governmental Organization

Coordination Commiee (NGOCC) to

strengthen role of NGOs working in FP in

coordination of national FP programmes.

Support NGOs capacity building in family

planning.

l Support Medical College Teaching Hospitals

by establishing FP service centers in each

medical college and including LAFP training

in doctor and nurse pre-service curriculum.

l Strengthen coordination of private sector.

Ensure that guidelines are in place for

adequate coordination of reporting on FP

services provided by private sector.

l Improve integration of FP services with

other services like immunization, HIV,

Postpartum, Post-abortion, morbidities,

urban health. Develop national FP service

integration strategy and operational

guidelines to implement the strategy. Pilot

new integration approaches in 2016 and scale

up the eective models in following years.

l Improve facility recording and reporting.

Strengthen and update recording/reporting

system as well as coordination with HMIS.

Develop M&E tools for private providers that

are in line with HMIS tool