176 International Family Planning Perspectives

Although governments develop family planning policies

to guide program design and implementation, these poli-

cies can have both intended and unintended consequences.

As a result, policies may need periodic revision to achieve

the desired outcomes. Over the last two decades, the gov-

ernment of Peru has instituted a series of laws and policies

designed to enhance access to family planning services and

commodities. In practice, these policies have not always

had their desired effect. This paper examines the policies

Peru’s Ministry of Health has developed and implement-

ed to promote access to family planning for all, and how

those policies have affected contraceptive prevalence,

method mix and source mix.

In this article, we review policies and laws relevant to

family planning and provide insight on how the family plan-

ning policies have evolved and affected access to services,

as well as how characteristics of and trends in the family

planning market* have changed over time. Our assessment

draws on multiple information sources, including family

planning market segmentation data and literature on Peru’s

family planning program. Additional sources, such as om-

budsman reports, user and provider interviews and health

facility studies, clarify specific points.

A historic overview of key family planning policies and

programs implemented in Peru, focusing on three time pe-

riods, 1985–1995, 1995–2000 and 2000–2004, provides

information on policies that have been put in place and the

degree to which they have affected access to family plan-

ning among the poor.

Establishing Peru’s Family Planning Program

In 1983, as a result of available donor funds, a favorable

political environment and the government’s concern for

population growth, the Ministry of Health began provid-

ing family planning services. It began with a vertical pro-

gram that was relatively autonomous in program content

and supervision and in use of financial resources and com-

modities.

1

This effort was followed in 1985 by the estab-

lishment of the first National Population Policy, which stat-

ed that individuals and couples should be provided with

information, health services and contraceptive methods,

with the exception of voluntary sterilization, to assist them

in making informed decisions about family size and fertil-

ity.

2

Under the first National Family Planning Program

(1987–1990), developed to implement the National Pop-

ulation Policy and financed by a combination of donor and

government funds, the Ministry of Health coordinated

public- and private-sector family planning programming

and established goals for reductions in fertility and targets

for increases in contraceptive use. Implementation of the

program began in 1988, and despite political support, faced

multiple challenges, including a national economic crisis,

public-sector reorganization and the Ministry of Health’s

limited service delivery capacity; as a result, it was not im-

plemented as broadly or as rapidly as envisioned. Despite

the program’s limitations, it contributed to a substantial

reduction in the country’s total fertility rate—from 4.1 in

1986 to 3.5 in 1991

3

—which was likely due to the increased

availability of contraceptives, especially in rural areas.

4

Peru’s second National Family Planning Program

(1991–1995), which also received considerable political

commitment, continued to focus on expanding service de-

livery in underserved and predominantly rural areas. This

expansion of services was financed by increased funding

from government, which paid 20% of program costs, and

donors, who paid 80%.

4

Annual government spending on

health in general increased from 52 soles (US$16) per capi-

ta during the late 1980s to 59 soles (US$18) per capita dur-

ing the period 1991–1995.

5

Meanwhile, annual donor in-

vestment in population-related activities in Peru increased

from US$5.2 million in 1987 to US$12.9 million in 1994

and, spurred in part by the focus of the International Con-

ference on Population and Development (ICPD) on fami-

ly planning and donor priorities in the late 1990s, to US$28

million in 1998.

6,7

In the early 1990s, in keeping with the worldwide trend

of user fees in the public sector, most Ministry of Health

facilities in urban areas charged clients for family planning

services and products, while free family planning was avail-

able in rural areas, where the majority of the poor reside.

In 1992, 41% of women reported obtaining family plan-

ning products and services from the commercial sector

(pharmacies and private providers), while 36% obtained

them from the Ministry of Health (see Figure 1).

3

Social

security and nongovernmental organizations served 18%

of women; precise information on method sources for the

remaining 5% was not available. The Ministry of Health’s

policy of targeting free services to poor people in rural areas

and levying service fees in urban areas likely provided an

opportunity for commercial family planning providers to

thrive: Individuals who could afford to pay for family plan-

ning products and services may have found it more con-

COMMENT

Family Planning Policies and Their Impacts

On the Poor: Peru’s Experience

James N. Gribble is

director of the

BRIDGE Project,

Population Reference

Bureau, Washington,

DC. Suneeta Sharma

is senior health

economist and

reproductive health

team leader, Health

Policy Initiative,

Constella Futures,

Washington, DC.

Elaine P. Menotti is

technical advisor,

U.S. Agency for

International

Development,

Washington, DC.

By James N.

Gribble, Suneeta

Sharma and Elaine

P. Menotti

*The components of the family planning market include providers (gov-

ernment, social security, commercial, social marketing and nongovern-

mental organizations), consumers (women of reproductive age, 15–49 years)

and contraceptive methods (long-term and temporary modern methods).

177Volume 33, Number 4, December 2007

Fund’s procurement mechanism.

9

Between 1992 and 2000, a time in which Peru’s public

sector was assuming an increasingly dominant role in the

family planning market, private providers found it difficult

to compete with such widespread provision of free or high-

ly subsidized products and services.

12

The commercial sec-

tor’s market share fell from 39% to 17% between 1992 and

2000. Between 1996 and 2000, the decline was driven pri-

marily by a 50% drop in market share for pharmacies (from

venient to purchase them from the numerous commercial

outlets available and forgo the opportunity costs associat-

ed with using Ministry of Health facilities (i.e., distance,

travel, quality of services).

Family Planning for All

In 1995, after the implementation of the ICPD Programme

of Action (under which Peru is a signatory) and with po-

litical support from the president, the Ministry of Health

instituted a policy to provide free family planning products

and services to all who wanted them. Donors provided

100% of Ministry of Health contraceptive commodities, as

well as substantial technical assistance and resources for

training; supervision; information, education and com-

munication; and other program components. As a result,

the Ministry of Health was able to direct its resources to

expansion of family planning service delivery. In 1994, the

Ministry of Health introduced an ambitious program (Salud

Básica) to expand its network of primary health care facil-

ities, whose services included family planning. The num-

ber of health posts, health clinics and health centers run

by the Ministry increased by more than 50% between 1995

and 2000, and more than 10,000 medical and paramed-

ical staff were added across the country. In addition, the

legalization of female sterilization as a contraceptive method

for all women in 1995 increased access to the method.

8

Annual government spending on health increased from 59

soles (US$18) per capita during the early 1990s to 93 soles

(US$29) per capita during the 1996–2000 period.

5

As a

result of both public-sector investments and donor sup-

port, the National Family Planning Program was deliver-

ing services through more than 6,000 facilities by the late

1990s.

9

The expansion in service delivery and availability of free

contraceptives in Ministry of Health facilities no doubt con-

tributed to the increase in contraceptive prevalence from

41% to 44% between 1996 and 2000—Figure 2. Overall,

women increased their use of modern methods from 27%

to 32%, with the poorest women increasing their modern

method use from 18% to 25% (Figure 3, page 178). In ad-

dition, the policy was responsible for the dramatic increase

in family planning market share for the Ministry of Health,

which rose from 59% in 1996 to 68% in 2000.

10,11

At the same time, donors were beginning to reduce con-

traceptive commodity donations to the government of

Peru,* potentially threatening the availability of contra-

ceptives. In response, the Peruvian government earmarked

funds for family planning in its annual budget in 1997 and

agreed to begin purchasing contraceptives in increasing

quantities. The government’s first purchase, however, was

not made until two years later, in 1999, when funding for

contraceptives was actually allocated for the first time, en-

abling the National Family Planning Program to purchase

contraceptives through the United Nations Population

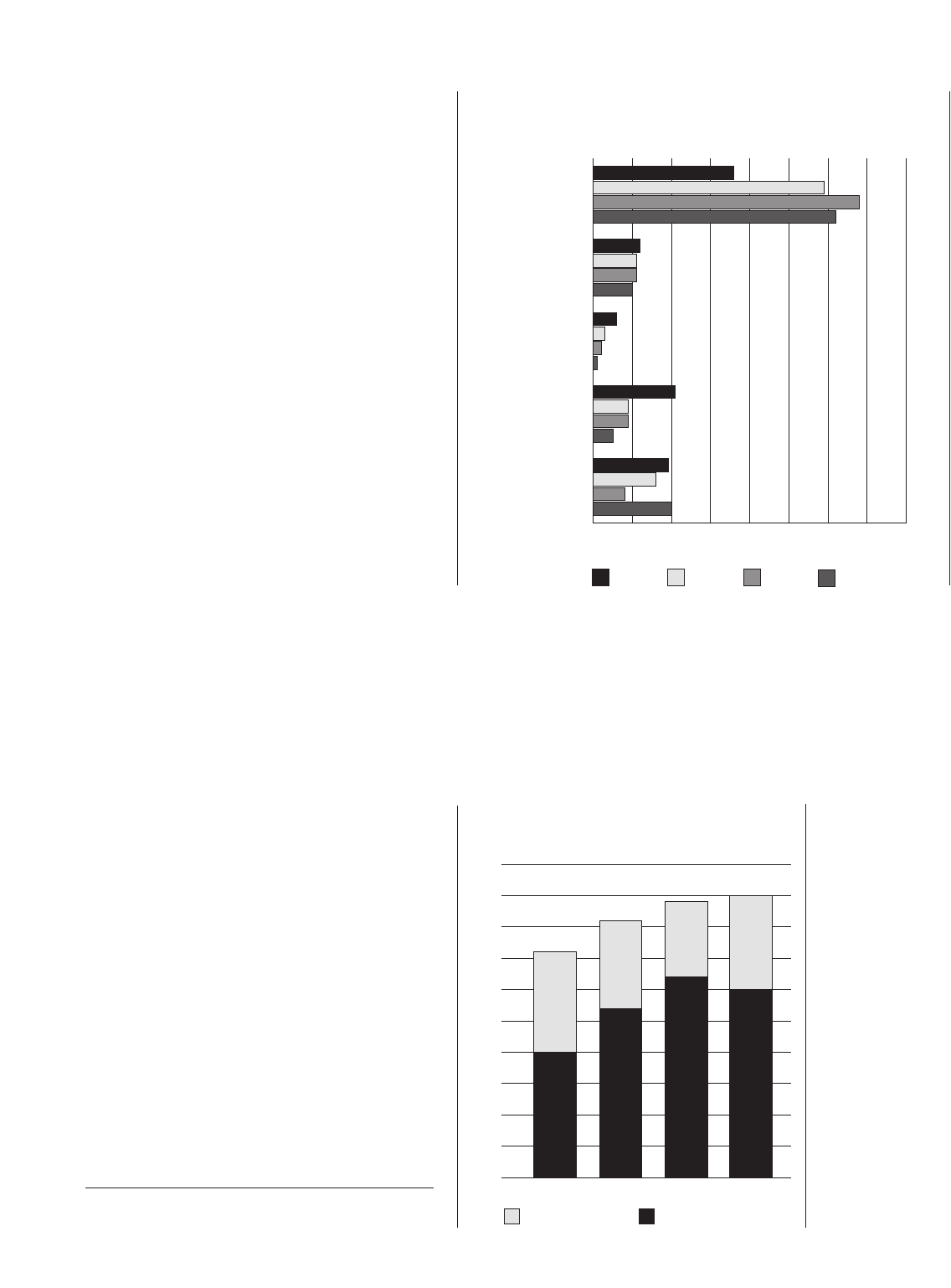

FIGURE 1. Among Peruvian women aged 15–49 practicing family planning, percent-

ages obtaining services and methods from specific sources, 1992–2004

2004

2000

1996

1992

0 1020304050607080

Pharmacies

Private providers

Nongovernmental

organizations

Social Security

Ministry of Health

% of women

FIGURE 2. Contraceptive prevalence, by type of method,

among Peruvian women aged 15–49, by year, 1992–2004

Traditional methods

Modern methods

0

10

20

30

40

50

2004200019961992

% of women

*On the basis of a combination of contraceptive prevalence, total fertility

and economic indicators, donors had decided that Peru was ready to move

toward more self-sustaining family planning efforts.

178 International Family Planning Perspectives

16% to 8%).

10,11

Total commercial sales of oral contracep-

tives and injectables decreased from 1.4 million units in

1995 to 1.1 million units in 1996—and continued to decline

consistently until 2001.

9

According to several studies, public-sector prices for tem-

porary family planning methods are one of the major

determinants of the use of commercial outlets for those

methods.

13–15

Their findings show that if high-quality con-

traceptive methods are available free of charge in Ministry

of Health facilities, private-sector users are likely to switch

to these outlets. From 1996 to 2000, the share of Ministry

of Health clients made up of women in the three upper so-

cioeconomic quintiles rose from 46% to 53%, while the

share accounted for by women in the two lower quintiles

decreased from 54% to 47% (Figure 4).* Use of pharma-

cies for contraceptive supplies declined from 17% to 7%

among women in the middle quintile and from 23% to 13%

among those in the upper middle quintile.

10,11

In other

words, women with the ability to pay were benefiting from

public subsidies.

The 1995 policy expanded access to family planning and

initially adopted the focus of the ICPD Programme of Ac-

tion on individual women’s needs, instead of population

control. In 1996, however, Peru’s family planning program

returned to employing the targets it had used when first

established.

16

By 1999, the government had changed its

service delivery strategy and renounced the use of targets

and quotas; measures were put in place to improve quality

of care, including procedures to ensure informed consent

for female sterilization.

8

Changes in Commitment to Family Planning

At the beginning of the current decade, program changes

within the Ministry of Health affected family planning’s

priority status on the national agenda. From 2000 to 2003,

some government officials and prominent figures in the

Ministry of Health who opposed family planning for moral

reasons undertook deliberate measures to restrict access

to family planning products, services and information in

Peru. These measures included publicly disputing that con-

doms and IUDs were safe and effective, blocking commodity

distribution and proposing modifications to the constitu-

tion and the general health law that would restrict access

to family planning.

9,16

Although these government officials were not success-

ful in altering or removing policies that supported Peru-

vians’ access to family planning, their efforts coincided with

the introduction of health sector reforms that affected the

way in which family planning services were managed and

delivered by the Ministry of Health. Since its inception in

the 1980s, the National Family Planning Program had been

vertically planned and managed by the Ministry of Health,

as was the case for all other national health programs. At

the service delivery level, family planning was provided by

the Ministry’s clinics, often having its own program ad-

ministration and providers. In 2001, however, to improve

efficiency and to reduce the costs of managing and deliv-

ering health services, the government combined all 14 na-

tional health programs into an integrated health model that

was based on the life course and reorganized the Ministry

of Health accordingly, decentralizing management func-

Family Planning Policies and Their Impacts on the Poor

FIGURE 3. Contraceptive prevalence, by type of method, among Peruvian women

aged 15–49 in the poorest and wealthiest quintiles, by year, 1996–2004

0

10

20

30

40

50

Wealthiest

Poorest

Traditional methods

Modern methods

Quintile

1996

2000 2004 1996 2000 2004

% of women

FIGURE 4. Percentage distribution of Peru’s Ministry of

Health clients, by socioeconomic status, according to year,

1996–2004

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

200420001996

Upper middle and wealthiest

Middle

Poorest and lower middle

% of women

*Through a principal components analysis, a household’s ability to pay for

family planning is established using a standard of living index based on

number of household assets. Households are then divided into quintiles

(poorest, lower middle, middle, upper middle and wealthiest) according

to standard of living. Here we calculated the standard of living index using

the 1996, 2000 and 2004 Peru Demographic and Health Surveys.

179Volume 33, Number 4, December 2007

cess to contraceptive methods, which included a reduction

in the availability of surgical contraception, limited access

to information about contraceptives, stockouts of contra-

ceptive methods and unauthorized fees for services that

were supposed to be free in health centers.

20

Perhaps as a result of reduced access to family planning

services and commodity stockouts in Ministry of Health

facilities, the reported number of abortions increased. About

35,000 cases of incomplete abortion were treated in Min-

istry of Health facilities in both 2000 and 2001; the num-

ber rose to 38,851 in 2002 and to 41,993 in 2003.

19

Another study of family planning providers operating

in Ministry of Health facilities, conducted between 2002

and 2004, provides further insight.

21

In the 2002–2003

round of the study, 34% of the 238 providers interviewed

reported that, in the 12 months prior to the survey, the

method supply was continuous; 40% thought that the sup-

ply was sufficient and 25% indicated that the supply was

both continuous and sufficient. However, in the 2003–2004

round of the study, only 6% of 242 providers interviewed

stated that the supply of contraceptives had been contin-

uous; 17% thought the supply of methods was sufficient

and 2% reported that the supply of methods was both con-

tinuous and sufficient. Also, in this round of the study, 83%

of providers said that when facing stockouts of contraceptive

commodities—especially injectables and oral contracep-

tives—they advised their patients to use another method

temporarily, with 60% providing a prescription to be filled

at a commercial outlet or pharmacy and 23% changing the

patient’s contraceptive method to one in stock. These find-

ings reveal not only reduced access, but also reduced qual-

ity of family planning services—which was likely to affect

use—especially among women who could not afford com-

mercial sector prices.

DISCUSSION

Peru’s family planning policies have, in general, been de-

signed to address all women’s needs. Some policies, how-

ever, focus particularly on the poor, in accordance with the

public sector’s mandate to serve people whose access to

and receipt of preventive and curative health services and

products depends on subsidies and assistance. The evidence

presented here suggests that the poor are particularly vul-

nerable to unanticipated policy outcomes, highlighting the

need for well-designed policies and significant thought

about both implementation and consequences. As Figure

4 shows, wealthier Peruvian woman made up an increas-

ing share of government family planning clients between

1996 and 2004. This fact reveals a universal lesson: Given

that developing countries have limited resources, provid-

ing universal coverage through the public sector, although

conceptualized as a strategy to reach the poor, often ends

tions to the regions, eliminating separate budgets and down-

sizing or reassigning family planning staff to other Ministry

of Health divisions. As a result, the Ministry of Health lost

its core expertise in family planning at the central level, along

with its ability to plan, supervise and monitor family plan-

ning services.

9

The change in the model of care created bar-

riers for family planning clientele, including less privacy,

lack of educational materials, long waiting times and the

requirement of a visit to the hospital or clinic pharmacy

after consultation.

1,17

Additionally, an economic crisis strik-

ing the country in the early 2000s decreased per capita ex-

penditures for health from 95 soles (US$30) in 2001 to 88

(US$27) in 2002 and 78 (US$24) in 2003.

5

During the same period, donors continued to reduce con-

traceptive commodity donations to the government of Peru.

In 2002, as part of the donor contraceptive commodity

phase-out plan, the government declared that contracep-

tives were strategic public health commodities,* which

helped to ensure that contraceptives received special pro-

tection and funding in the national budget. However, the

government’s inability to compensate for decreased donor

funding left the Ministry of Health unable to meet the de-

mand for contraceptives. As a result, from 2002 through

2004, government facilities experienced stockouts of con-

traceptives. Logistic problems, such as poor planning and

information systems, a long supply chain and insufficient

or incorrect commodity mix, exacerbated the problem.

After a steady increase during the previous decade, con-

traceptive use stagnated at 44% in 2004, likely a result of

stockouts and a weakened family planning program. Mod-

ern method use declined in 2004, especially among those

in the poorest quintile, but stayed stable among the wealth-

iest quintile. Although use of traditional methods declined

from 14% in 1996 to 12% in 2000, their use rose again to

15% in 2004. This increase occurred in all quintiles except

the wealthiest. In the poorest quintile, use of traditional meth-

ods increased from 14% to 23% between 2000 and 2004.

18

Also between 2000 and 2004, Ministry of Health’s mar-

ket share shrank from 68% to 62%; this was most likely

due to the government’s insufficient funding for com-

modities. Interestingly, during the same period, the com-

mercial sector’s market share rebounded from 17% to 25%,

dominated by pharmacies. The shift back to the commer-

cial sector was led by women of the two wealthiest quin-

tiles, who doubled their use of pharmacies between 2000

and 2004.

11,18

Studies that focus on the experiences of public- and

private-sector providers further elucidate the changes that

took place in the Ministry of Health program between 2000

and 2004. One study found a decline in family planning

services in the Ministry of Health, including an absence

of follow-up, evaluation and training activities; a lack of

regard for family planning and reproductive health as

national priority issues by certain health officials and polit-

ical leaders; and periods of stockouts of contraceptives that

affected users for many months.

19

The Ombudsman’s

Office reported consumer complaints about restricted ac-

*Many of Peru’s programs, such as those for tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS, and

sexual and reproductive health, have been converted from vertical pro-

grams into “Health Strategies,” interventions for which it is the responsi-

bility of the government to carry out objectives. The Ministry of Health is

therefore responsible for making available to the public the medicines and

supplies critical to the success of these strategies.

180 International Family Planning Perspectives

up serving a considerable proportion of people who can

afford to pay for care and restricts access among those peo-

ple who can least afford it.

In Peru, increasing service availability and providing free

donated contraceptives through the Ministry of Health in-

creased contraceptive prevalence for all women in the short-

term, but likely reduced the role of the commercial sector

and shifted some wealthier clients to the Ministry of Health.

The 1995 policy decision had the positive impact of in-

creasing contraceptive use among women in the lowest two

socioeconomic quintiles and those in rural areas. From 1996

to 2000, women in the poorest quintile increased use of

modern methods. However, from 2000 to 2004, use of mod-

ern methods declined in the poorest quintiles, and use of

traditional methods among these groups increased. The

general trend between 1996 and 2004 shows that the pro-

portion of Ministry of Health clients from the wealthiest

quintiles increased over time and that the proportion from

the two poorest quintiles decreased. In light of the fact that

the Ministry of Health’s per capita financial resources have

declined, priority should be given to refocusing those re-

sources on the poorest groups, who have no other option

for health services and products.

Although the overall trend in contraceptive prevalence

shows a leveling off of modern method use from 2000 to

2004, closer analysis by socioeconomic subgroups shows

that the plateau in levels of use was not universal; use of

modern methods declined in the two poorest quintiles be-

tween 2000 and 2004. A number of factors could explain

why poor women—especially those in rural areas—decreased

their use of modern contraceptives and increased their use

of traditional methods: reduced access to family planning

facilities, methods of choice or information in rural areas

as a result of service integration; contraceptive stockouts

in rural Ministry of Health facilities; levying of unofficial

fees in public health centers; the inability to pay for meth-

ods in private-sector outlets; and the public discrediting of

modern methods. Even if services for the poor were read-

ily available, misinformation often affects women’s inter-

est in seeking family planning methods and services. A re-

cent study conducted among rural, poor Peruvian women

found that misinformation about family planning meth-

ods discourages contraceptive use; however, these women

also indicated a strong interest in receiving information

about family planning methods.

22

These findings also sug-

gest that for policies designed to improve access among the

poor to be effective, they must also address a wider range

of barriers that undermine utilization of services.

Improving Access Among the Poor

Currently, the government of Peru is taking steps to address

the decline in modern method use among the poor and to

improve access to accurate information. The use of condi-

tional cash transfers, which is in the process of being im-

plemented, and the expansion of services under social in-

surance programs may increase access to modern family

planning methods among the poor.

•Conditional cash transfers. Peru is in the early stages of

rolling out a conditional cash transfer program as part of

a poverty alleviation strategy. To date, the program has been

implemented in 14 of Peru’s poorest regions. The program

provides 100 soles monthly (approximately US$31) to

women who complete certain requirements, which include

registering births, immunizing their children, obtaining

prenatal care and supplementary nutrition and ensuring

their children’s school attendance. In addition, women have

the opportunity to participate in information sessions on

family planning and reproductive health.

•Social insurance programs. Peru has implemented a so-

cial insurance program that covers a range of curative and

preventive health services for children, adolescents, preg-

nant women, the very poor and other vulnerable groups.

In March 2007, the president of Peru and the minister of

health signed a resolution to expand the package of bene-

fits to include provision of family planning services and com-

modities. Given that the social insurance program is actu-

ally more successful in reaching the poor in general with

its current care package than the Ministry of Health is in

reaching the poor with family planning,

23

it is a promising

mechanism for ensuring that the poor have access to fam-

ily planning information, services and methods.

Conclusion

Peru’s experience reveals that when well-intentioned poli-

cies are implemented, they can have adverse outcomes on

the people they are designed to help. Consequently, poli-

cymakers must think through both the short- and long-term

consequences of policies prior to implementation. More-

over, as the experience of Peru demonstrates, they should

continuously monitor and evaluate how policies are being

implemented and be willing to make adjustments when it

is clear that a policy is not achieving its desired outcomes.

REFERENCES

1. Subiria, G, Informe de disponibilidad asegurada de insumos anti-

conceptivos región Junín, internal document, Lima, Peru: Iniciativa de

Políticas en Salud, 2006.

2. Sobrevilla LA, Peru: population and policy, Population Manager, 1987,

1(1):40–44.

3. Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática, Asociación Benéfica

PRISMA and Macro International, Perú Encuesta Demográfica y de Salud

Familiar, 1991/1992, Columbia, MD, USA: Macro International, 1992.

4. Angeles G, Guilkey DK and Mroz TA, The determinants of fertility

in rural Peru: program effects in the early years of the national family

planning program, Journal of Population Economics, 2005, 18(2):367–

389.

5. Asociación Pro Derechos Humanos (APRODEH) and Centro de

Asesoría Laboral del Perú (CEDAL), Informe Sobre la Situación de los

Derechos Económicos, Sociales y Culturales 2002–2003: Dos Años de

Democracia . . . y ¿los DESC?, Lima, Peru: APRODEH and CEDAL, 2005.

6. United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), Global Population

Assistance Report 1995, New York: UNFPA, 1997.

7. UNFPA, Financial Resource Flows for Population Activities in 2004, New

York: UNFPA, 2006.

8. Leon FR, Providers’ Compliance with Quality of Care Norms, Lima, Peru:

Population Council, 1999.

9. Taylor PA et al., Peru: Contraceptive Security Assessment, September 1–12,

Family Planning Policies and Their Impacts on the Poor

181Volume 33, Number 4, December 2007

International, Perú Encuesta Demográfica y de Salud Familiar, 2004,

Calverton, MD, USA: ORC Macro, 2004.

19. Ferrando D, El aborto clandestino en el Perú: nuevas evidencias,

PowerPoint presentation, Lima, Peru: Flora Tristan and Pathfinder

International, 2004.

20. Defensoria del Pueblo, La anticoncepción quirúrgica y los dere-

chos reproductivos III, casos investigados por la Defensoría del Pueblo,

Informe Defensorial No. 69, Lima, Peru: Defensoria del Pueblo, 2002.

21. Proyecto POLICY/Peru, Encuesta de Proveedores de Planificación

Familiar en el Ministerio de Salud, Lima, Peru: Proyecto POLICY, 2005.

22. Diaz M, Reporte de Actividades: Grupos Focales con Mujeres Pobres,

Lima, Peru: Iniciativa de Políticas en Salud, 2006.

23. Petrera M, Evaluación de la Inclusión de Atenciones de Planificación

Familiar en los Planes de Beneficios del Seguro Integral de Salud, Lima, Peru:

Iniciativa de Políticas en Salud, 2006.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Roberto Lopez, Patricia Mosta-

jo, Varuni Dayaratna, Rebecka Lundgren, Nancy Murray, Carol

Shepherd and Gracia Subiria for reviewing drafts of this comment.

The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) Health

Policy Initiative provided partial funding for this project under con-

tract GPO-I-01-05-00040-00. The views expressed in this comment

are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of

USAID or the U.S. government.

Author contact: jg[email protected]

2003, Arlington, VA: John Snow/DELIVER, and Washington, DC: Futures

Group International/POLICY II, 2004.

10. Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática and Macro

International, Perú Encuesta Demográfica y de Salud Familiar, 1996,

Calverton, MD, USA: ORC Macro, 1996.

11. Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática and Macro

International, Perú Encuesta Demográfica y de Salud Familiar, 2000,

Calverton, MD, USA: ORC Macro, 2000.

12. Sharma S, Gribble JN and Menotti EP, Creating options in family

planning for the private sector in Latin America, Pan American Journal

of Public Health, 2005, 18(1):37–44.

13. Foreit KGF, Broadening commercial sector participation in repro-

ductive health: the role of public sector prices on markets for oral con-

traceptives, Commercial Market Strategies Technical Paper Series,

Washington, DC: Commercial Market Strategies, 2002, No. 3.

14. Bulatao R, What influences the private provision of contraceptives?

Commercial Market Strategies Technical Paper Series, Washington, DC:

Commercial Market Strategies, 2002, No. 2.

15. Winfrey W et al., Factors influencing the growth of the commer-

cial sector in family planning service provision, POLICY Project Working

Paper, Washington, DC: Futures Group International, 2000, No. 6.

16. Coe AB, From anti-natalist to ultra-conservative: restricting repro-

ductive choice in Peru, Reproductive Health Matters, 2004, 12(24):56–69.

17. Sarley D et al., Options for Contraceptive Procurement: Lessons Learned

from Latin America and the Caribbean, Arlington, VA, USA: DELIVER,

and Washington, DC: USAID Health Policy Initiative, 2006.

18. Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática and Macro