Smoke and mirrors

The role of World Bank and IMF in

shaping social security policy in the

MENA region

Sarina D. Kidd

ISSPF Working Paper Series:

Shifting the Paradigm

April 2022

Issue: 04

Executive summary

i

Executive summary

Countries in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region face a number of challenges,

including fiscal instability, conflict, civil unrest and high unemployment. A robust social

security system is an essential means of reducing inequality and increasing the economic

growth of a country. However, across the MENA region, social security systems are failing

to reach the majority of the population. Further, while fuel and food subsidies have

historically been regarded as the main means of delivering a degree of income security

for much of the population, these measures have been scaled back in recent years. The

schemes that are designed to compensate for such subsidy removal, however, are limited

in reach and, as a result, many people receive less from the State than before. This is

especially an issue when, across Arab States, there are widespread low incomes and high

rates of inequality.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank are two of the most significant

international financial institutions (IFIs) in the MENA region. They have played a critical

role in influencing social policy, encouraging countries – through the provision of loans

and technical assistance – to introduce austerity measures in order to scale back fiscal

costs. The most significant means in which the IFIs impact on social security policy is

through the provision of loans to governments. These loans are often attached to

conditions linked to disbursement, and may specify, for example, that a country must

implement a social registry (a mechanism for undertaking poverty targeting) or introduce

sanctions. If the condition is not met, disbursement, or a tranche of the funds, may be

withheld. It can be extremely difficult for a government to change the design of a social

security scheme if it does not align with one of the conditions in the loan.

The social security package that the World Bank and IMF promote

When promoting structural adjustment measures – such as subsidy reform – the IMF and

World Bank generally advise that part of the savings should be re-allocated to “well-

targeted,”, “pro-poor”, “efficient” social security schemes. However, the package that is

promoted aligns with a poor relief model and is neither well-targeted nor pro-poor. This

contrasts with an inclusive lifecycle approach to social security, in which levels of

investment are high due to broad coverage and high transfer values. States are duty

bearers that are obliged to provide a minimum social security floor, which addresses key

risks across the lifecycle, including old age, disability, childhood and unemployment.

Schemes are offered on a universal or near universal basis, for social security is an

individual entitlement – that is, a human right. Components of the IFIs’ social security

packages are discussed below.

Executive summary

ii

Low Coverage

The schemes promoted by the IMF and World Bank have small budgets and low coverage.

This means that the majority of the population– i.e. the “missing middle” in the informal

economy – are not reached by either a social insurance or tax-financed scheme. For

example, in a context of fuel subsidy reform, the World Bank has supported the

Government of Tunisia to establish the Amen Social Programme to replace the Programme

Nationale d’Aide aux Familles Necessiteuses (PNAFN). The Permanent Cash Transfer (PCT)

component aims to increase coverage from 8 to 10 per cent of the population. As a result,

many Tunisians who are living on low incomes, but are not benefiting from the social

insurance system, will not receive any social security benefits.

The IFIs’ messaging can confuse policymakers and practitioners into thinking that

schemes with low coverage generate greater impacts than those with higher coverage.

For example, programmes with high coverage are often referred to as “poorly targeted”

and “inefficient” when compared to smaller poverty-targeted schemes, which the IFIs

describe as “pro-poor”. This is despite the fact that inclusive lifecycle schemes reach more

people living on low incomes due to their higher coverage. For example, in Morocco, the

World Bank noted that the government’s planned universal child benefit is “likely to be

progressive” (emphasis added), in contrast to a scheme with 40 per cent coverage, which

would be “even more progressive.” Yet, the universal scheme would be much more effective

in reaching the poorest children. Meanwhile, in Tunisia, the World Bank has argued that a

proposed poverty-targeted Family Allowance would reach a higher share of beneficiaries

in the first wealth decile than the country’s subsidy programmes, even though it would

only be provided to around 10 per cent of children aged 0-5 years. At first glance, it

therefore appears that the Family Allowance will reach far more beneficiaries in the

poorest decile than schemes with higher coverage. Therefore, it appears to the uncritical

eye to be more “pro-poor”. In absolute numbers, far more households in the lowest decile

benefit from schemes with universal coverage than from the targeted Family Allowance.

Poverty targeting

In order to implement a scheme with low coverage, the IFIs try to deliver it to the poorest

segments of the population. Identification is normally achieved through a proxy means

test (PMT). The IFIs promote the PMT as a “scientific” mechanism which they portray as

efficient and accurate. In reality, it is a highly inaccurate process, with selection often

being little more than random. For example, Egypt’s Takaful and Karama Programme

(TKP) has an exclusion error of 55 per cent for the poorest quintile and 75 per cent for the

second quintile.

These limitations are due to a number of reasons. For example, it can be difficult to

differentiate who is the poorest when the majority of persons are living on low incomes.

Executive summary

iii

Second, household income and consumption levels fluctuate, which means that

households living under the poverty line during one year are not the same as those living

under the poverty line the next. This is especially the case in countries experiencing

conflict, such as Yemen and Iraq, or those in the midst of a financial crisis, such as

Lebanon. Exclusion errors are further exacerbated in the absence of recent national

household surveys. For example, both Yemen and Lebanon’s PMTs are based on

household surveys that are more than a decade old and no longer reflect the current

situation of the countries. The PMT formulae are, therefore, highly inaccurate.

Despite evidence showing that poverty targeting results in high exclusion errors, the IFIs

continue to use language that can mislead policy makers into thinking that this is not the

case. When assessing the impacts of a poverty-targeted programme, the institutions often

undertake simulations that assume that a programme will have “perfect targeting”. The

results, therefore, exaggerate the effectiveness of a scheme.

Social registries

Linked to the implementation of a PMT is the development of a social registry. A social

registry is a database that includes household data, with the aim of selecting households

for poverty-targeted programmes through a PMT. The World Bank has supported the

implementation of social registries in countries such as Yemen, Egypt, Morocco, Tunisia,

Iraq, Palestine, and Lebanon, noting that the social registry “allows for better targeting, thus

making social transfers more pro-poor.” However, as social registries use PMTs they carry

the same design flaws as the PMT and cannot be used to accurately identify the poor.

The IFIs aim to make the social registry a gateway to coordinate countries’ social

programmes. In Morocco, for example, a World Bank loan includes a disbursement linked

indicator, specifying that the government will implement a law, setting forth that the

social registry will be the entry point for any “safety net programmes” that are introduced.

However, social registries are not designed to identify recipients for modern, lifecycle

social security systems, based on individual entitlements, as they do not hold information

on the majority of the population nor on individuals within households. By presenting

social registries as the coordinating mechanism for social security schemes, this pre-

supposes that social programmes will be household-based and poverty-targeted. It is,

therefore, a means of ensuring that countries continue to implement small, poor relief

schemes. As discussed below, Morocco is currently designing a universal child benefit.

Depending on the operational definition of “safety net programmes” it could potentially

put the universal child benefit in legal jeopardy as it will not need to utilise the social

registry.

If the World Bank wants to help countries to strengthen their delivery systems and

develop useful databases, they could do so by supporting countries to develop a Single

Executive summary

iv

Registry, and/or strengthening a civil registry, which could then hold information on the

entire population.

Household Benefits

In general, IFI-supported schemes are delivered to the household rather than to the

individual. This contrasts with an inclusive lifecycle system, in which individuals are

rights-holders who are entitled to social security. Paying benefits to a household does not

take into account the intra-household distribution of wealth and power dynamics: there is

no guarantee that all members of the household would benefit from the scheme. Further,

many people with no personal income are excluded, because their household is assessed

as non-poor. While some poverty-targeted programmes – such as Lebanon’s National

Poverty Targeted Programme (NPTP) and Yemen’s Social Welfare Fund (SWF) – target the

cash transfer at specific categories of households, including households with a vulnerable

individual, this does not address the core challenge. Unless the vulnerable individual is

the recipient of the cash by being the household head, there is no guarantee that they

will benefit from the scheme. Likewise, many persons with disabilities do not receive

income security because their households do not qualify for the programme. Jordan’s

Takaful scheme demonstrates a further limitation of household benefits: only the head of

the household may apply, which could result in the exclusion of women if they wish to

apply, but the male head of the household does not.

Conditions, sanctions and workfare

Many of the favoured programmes of the World Bank and the IMF are ones in which

recipients have to comply with certain behaviours in order to achieve their funds. This can

be in the form of a conditional cash transfer (CCT) or a workfare programme. Under

Egypt’s TKP, for example, CCTs are offered to young families under the Takaful

component, whereas unconditional transfers are offered to vulnerable categories of

people, such as older persons or persons with disabilities. Here, the “deserving” are older

people or persons with disabilities who do not need to change their behaviour, because

they are regarded as poor due to lacking labour capacity, while working age parents with

children must prove their deservingness by attending four health check-ups a year for

children younger than 6 and ensuring children aged 6-18 years attend school at least 80

per cent of the time, or risk being sanctioned by losing their benefits.

The implementation of conditions is problematic as it requires equal performance despite

unequal contexts and circumstances. Recipients are sanctioned if they do not comply,

despite their clear need. Indeed, conditions are arguably not suitable for those countries

in the MENA region that have limited services or are experiencing conflict. While the

World Bank has claimed that there is significant evidence that CCTs have had positive

impacts worldwide, global evidence points to the opposite. In Morocco, a study – partly

Executive summary

v

funded by the World Bank – found that children were more likely to attend school when

receiving an unconditional transfer, rather than a CCT which was conditional on school

attendance. Despite this evidence, it was a CCT that was established.

Undermining governments’ own paradigm shifts in policy thinking

When countries aim to introduce more inclusive lifecycle schemes, the IFIs can act to

undermine them. Morocco, for example, was the only country in the MENA region to

spend more than 2 per cent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) on a minimally adequate

stimulus to address the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. The response was apparently

so popular and effective that the country has announced that it will increase its old age

pension coverage and universalise the Family Allowance Programme, a child benefit.

While the World Bank has ostensibly committed to supporting the implementation of the

Family Allowance, it has incorrectly claimed that a targeted version of the scheme would

be “even more progressive”.

Indeed, the IFIs often promote schemes with low budgets with the argument that

countries do not have the fiscal space to implement a universal lifecycle scheme. This can

be observed in Tunisia, in which a poverty-targeted Family Allowance, aimed at

households with children aged 0-5 years, is being piloted. The World Bank notes that the

full expansion of the scheme to all households enrolled in the Amen Social programme

will “cost about 0.03 percent of GDP” and that it is considerably more cost-effective than

Tunisia’s energy subsidies which amount to more than 2 per cent of GDP.

A budget of 0.03 per cent of GDP is miniscule, especially when considering the proposed

budget of Morocco’s Family Allowance, which would cost 1 per cent of GDP. The World

Bank argues that Tunisia’s small scheme is the first step towards the government

implementing a Social Protection Floor, and that it will support “progressive universality”

with the justification that there is insufficient fiscal space to implement a scheme with

higher coverage (a debatable proposition). Yet, when the Government of Morocco is

willing to develop a minimum Social Protection Floor for all children in the country, and

shows that it has the fiscal space to fund the scheme, the World Bank is still opposed.

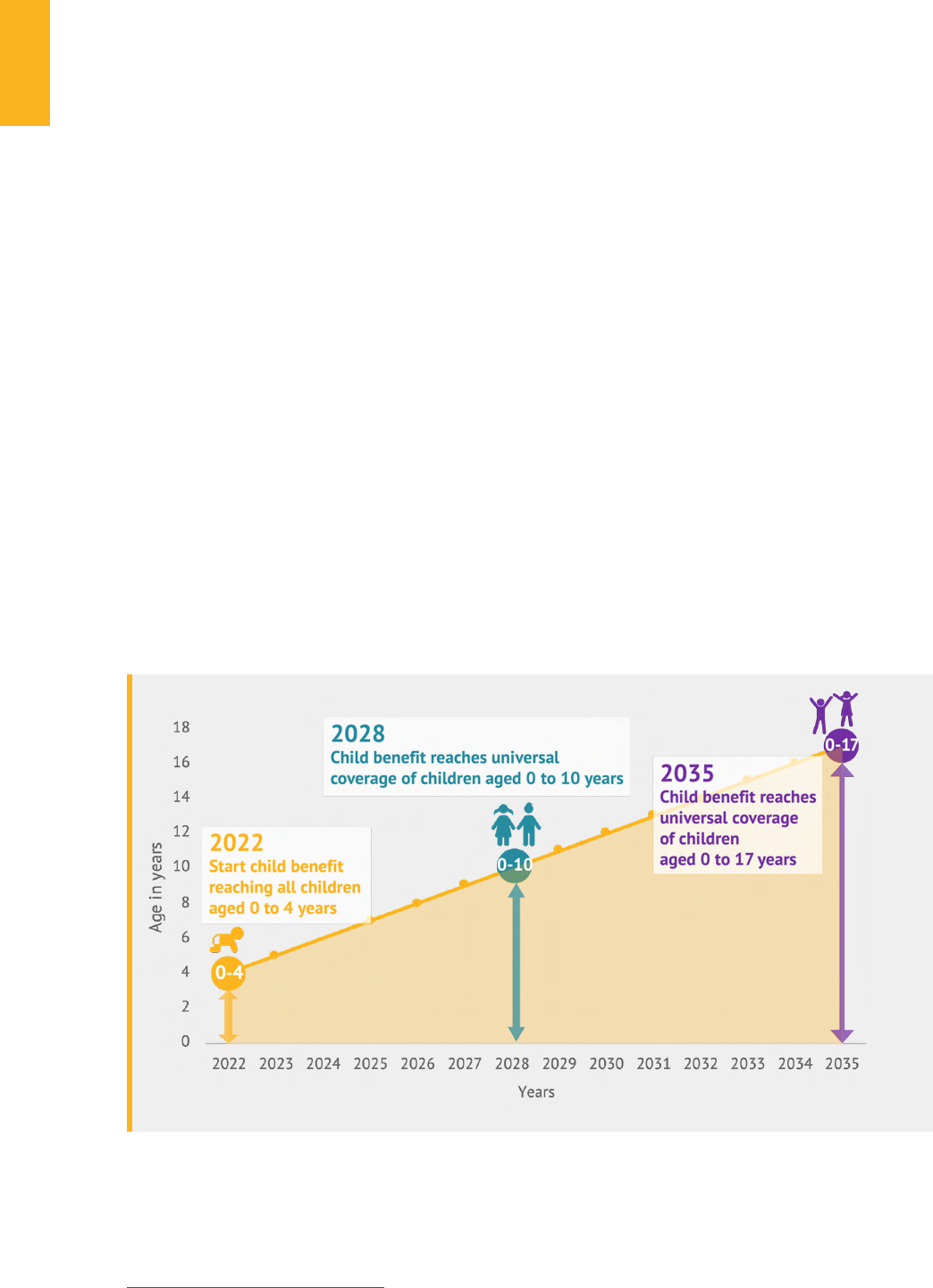

Progressive universality under a paradigm of poverty targeting is an oxymoron. A more

effective means of promoting universality – while managing fiscal constraints – is to

deliver a lifecycle benefit initially to a specific age group – for example, all older persons

aged 80+ – and then lower the eligibility age later. Or, in the case of a child benefit, it can

be offered initially to all children belonging to a younger cohort and coverage can

increase over time if the children are not exited from the scheme until they reach 18

years of age. The paradigms that promote poor relief and inclusive lifecycle schemes are

diametrically distinct, and the gradual expansion of schemes based on the principle of

Executive summary

vi

universality entrenches a rights based approach to social security as well as greater

effectiveness, sustainability and popular support.

Consequences of the IFIs’ approach

Although the IFIs promote their approach to social security as progressive and pro-poor,

in reality, poor relief can have a range of negative consequences.

Minimal impacts on poverty reduction, wellbeing and economic growth

Tax-financed social security systems play a key role in reducing inequality by

redistributing wealth from more affluent segments of society to the rest of the

population. However, in order to achieve this effectively, schemes must be inclusive, with

high coverage and transfer levels. Tackling soaring poverty and reducing inequality also

has significant impacts on a country’s economic growth. Investment in inclusive social

security builds human capital and increase labour supply; mitigates shocks and

production losses; drives demand and economic activity; fosters social cohesion; and

reduces inequality – all of which promote a virtuous circle of economic growth and

sustained investment in social security.

An increase in shame, stigma and social tensions

Poverty targeting can dehumanise beneficiaries, making them feel ashamed and

embarrassed to be enrolled on a poor relief programme. In addition, the enforcement of

sanctions in CCTs can undermine recipients’ dignity since they are not treated as free and

autonomous agents. Poor relief can also increase social tensions in communities. This is

especially the case when people who are eligible, or who consider themselves to be living

on low incomes, are unable to access programmes. Social tensions are further worsened

by the fact that targeting mechanisms such as PMTs are often poorly understood by

communities due to their complex nature.

Weakening the social contract and limiting fiscal space

When the majority of a population do not benefit from a social security system, they are

unwilling to pay taxes to invest in it. Further, schemes that employ conditions and

sanctions, or are poverty targeted, are less likely to be enshrined in law. Therefore, the

population do not feel entitled to the scheme.

In contrast, schemes with higher coverage receive greater public support and, as a result,

are more sustainable both financially and politically. Not only do such schemes attract

higher taxes and promote economic growth, which results in greater fiscal space being

dynamically generated, but they can become an important political tool. For example,

political parties may promise to increase coverage levels, or transfer values, during

Executive summary

vii

elections, which, when done well, can strengthen democracy. They are also, not

surprisingly, more likely to be grounded in legislation as enforceable rights.

In fact, inclusive lifecycle schemes attract higher investment over time due to their

popularity. Therefore, greater fiscal space grows out of the universality of social security

schemes.

In a region where trust in the state to implement effective social security systems is low,

it is essential that governments implement programmes that reach more than just a small

section of the population. Schemes with broader coverage are important if states are to

win the trust of their populations. For example, in 2017, Iran decided – with

encouragement from the IMF – to target its universal cash transfer scheme (which had

been implemented to compensate for subsidy reform measures). In a context of declining

living standards, the reform proved to be extremely unpopular, leading to protests in

December 2017.

Undermining countries’ abilities to build progressive, modern systems

The promotion of poor relief schemes has limited countries’ abilities to build modern,

inclusive social security systems. This has been especially noticeable during the COVID-19

pandemic, in which Morocco was the only country in the MENA region to invest at least 2

per cent of GDP in a social security response, which has been suggested as a minimally

adequate fiscal stimulus to support economic recovery. It is no surprise that, out of all the

countries in the MENA region, Morocco is the only one that now appears to be making

significant strides towards strengthening its old age pension and child benefit schemes.

Poor relief schemes continue to be promoted by the IFIs to address the impacts of the

pandemic. This reality in the MENA region contrasts with the rhetoric that the IFIs have

provided about the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, the World Bank has stated that:

“Governments should consider developing integrated, universal social protection systems to

support both the goal of achieving universal social protection by 2030 and the goal of

accelerating the growth of better jobs.” However, this is window dressing and not reflective

of what is occurring on the ground. The continuing promotion of poor relief schemes,

which operate under a neo-liberal paradigm and utilise poverty narratives, will hinder

governments’ attempts to shift to a rights-based paradigm.

Why do IFIs promote poor relief schemes?

There are many reasons why the IMF and World Bank promote poor relief schemes. Firstly,

they are guided by ideological thinking. As discussed above, low levels of investment in

social security systems align well with a neo-liberal vision of low taxes and a small state.

Executive summary

viii

This viewpoint is likely exacerbated by negative poverty narratives, which can justify why,

for example, conditions and sanctions should be attached to benefits.

Second, the IFIs’ messaging – even when it ignores global evidence – creates smoke and

mirrors that confuse policy makers. In Mongolia, for example, the World Bank stated that

the universal child benefit was “not … well-targeted and not effective in protecting the poor”,

despite the scheme reaching virtually all children living on low incomes. Policymakers

and practitioners who do not necessarily hold negative poverty narratives themselves,

could therefore be misled by the IFIs’ messaging into thinking that poor relief schemes

are indeed more effective at alleviating poverty. Or, they might come to believe that there

is no fiscal space to gradually implement a universal lifecycle system.

Third, there are financial incentives to what the IFIs do because ultimately, the IFIs are a

combination of banks that have to lend money to survive and consultancy firms that have

to cover their staff costs. A social registry, for example, is a product that the World Bank is

promoting strongly globally, as it can be financed by a loan and give work to the

institution’s staff. In addition, poor relief schemes – through the introduction of

conditions or workfare – can be sold as productive programmes to governments, who

would never dream of taking a loan for an unconditional poor relief programme or,

indeed, for universal schemes.

Finally, inclusive lifecycle schemes reduce the IFIs’ influence in a country. The IFIs would

have countries believe that modern lifecycle schemes are not good for business, when, in

fact, the opposite is true. Although the IFIs argue that lifecycle schemes are not efficient,

and that they cost too much to be fiscally sustainable, as discussed above, schemes with

high coverage are more popular and therefore, taxpayers are more willing to fund them.

Consequently, as countries transition towards implementing lifecycle schemes which

receive support from large sectors of the population, governments are less likely to take

out loans, and the IFIs lose their influence in the country.

Conclusion

The MENA region is at an important juncture. With subsidy reform looming large and the

impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic likely to be felt for years to come, it is now more

important than ever that the region experiences a paradigm shift in its approach to social

security. Despite evidence showing that inclusive, lifecycle schemes are more effective at

reaching persons living on low incomes, the IFIs often use smoke and mirrors to persuade

policy makers that this is not the case. Although the IFIs claim that poor relief schemes

are “pro-poor”, only a small segment of low-income households are actually reached. In

reality, therefore, the IFIs’ approach to social security is pro-rich, since a smaller social

security system entails low taxes, which benefits the rich. Further, when a government

Executive summary

ix

moves towards implementing an inclusive, modern lifecycle social security system, it is

also taking measures to reduce the IFIs’ influence within the country. This can help

explain why there is a reluctance from the World Bank and IMF to promote fiscally and

politically sustainable schemes.

There are some indications of paradigm shifts within the MENA region. Morocco, for

example, has announced that it will universalise its child benefit and increase the

coverage of its old age pension. However, without a serious shift in institutional approach,

the two IFIs will hinder governments’ attempts to develop inclusive, modern social

security systems, build the social contract and drive economic growth. More worryingly,

poor relief, if it continues as the dominant approach, will continue to undermine trust in

government, weaken the prospects for democracy, and increase the risk of social unrest,

the last thing that the region needs.

Acknowledgements

x

Acknowledgements

This working paper was produced with funding from a Ford Foundation grant titled

“Shifting the paradigm: building inclusive, lifecycle social security systems in the MENA

region”.

1

The report was prepared under the guidance of Shea McClanahan (Development

Pathways) and Stephen Kidd (Development Pathways) and has benefited from valuable

comments and feedback from Alexandra Barrantes (Development Pathways) and Chafik

Ben Rouine (Tunisian Observatory of Economy). Daniel Hughes (Development Pathways)

provided research support.

1

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license,

visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA

94042, USA.

Table of contents

xi

Table of contents

Executive summary ......................................................................................................................... i

Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................ x

Table of contents .......................................................................................................................... xi

List of Acronyms ........................................................................................................................... xii

1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 1

2 Context .................................................................................................................................... 4

3 The World Bank and IMF’s Approach to Social Security .................................................... 8

3.1 Low coverage ................................................................................................................................... 9

3.2 Poverty targeting ......................................................................................................................... 15

3.3 Social registries ............................................................................................................................ 18

3.4 Household benefits ..................................................................................................................... 20

3.5 Conditions, sanctions and workfare ...................................................................................... 22

3.6 Undermining more universal schemes ................................................................................ 25

3.7 The IFI approach in the MENA region can be found around the world ................... 28

4 Consequences of the World Bank and IMF’s approach ................................................... 29

4.1 Minimal impacts on well-being and economic growth ................................................. 29

4.2 Shame, stigma and social tensions ....................................................................................... 31

4.3 Weakening the social contract and limiting fiscal space ............................................. 33

4.4 Accountability of governments to their populations is weakened ............................ 35

4.5 The ability of countries to build inclusive, modern systems is undermined ......... 35

5 Why do the IFIs promote poor relief schemes? ............................................................... 37

6 Conclusion ............................................................................................................................ 39

Bibliography ................................................................................................................................. 41

List of Acronyms

xii

List of Acronyms

CCT

COVID-19

GDP

IFI

IMF

LCT

MENA

MIS

NAF

NPTP

PCT

PDS

PMT

PNAFN

PNCTP

PPP

SWF

TKP

UCT

US$

Conditional Cash Transfer

Coronavirus Disease 2019

Gross Domestic Product

International Finance Institute

International Monetary Fund

Labelled Cash Transfer

Middle East and North Africa

Management Information System

National Aid Fund

National Poverty Targeting

Permanent Cash Transfer

Public Distribution System

Proxy Means Test

Programme Nationale d’Aide aux Familles Necessiteuses

Palestinian National Cash Transfer Programme

Purchasing Power Parity

Social Welfare Fund

Takaful and Karama Programme

Unconditional Cash Transfer

United States Dollars

1 Introduction

1

1 Introduction

Countries in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region face a number of challenges,

including fiscal instability, conflict, civil unrest and high unemployment. A robust social security

system

2

is an essential means of reducing inequality and increasing the economic growth of a

country. However, across the MENA region, social security provisions are inadequate and fail to

reach the majority of the population.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank are two of the most significant

international financial institutions (IFIs) in the region. They have played an important role in

influencing social policy, encouraging countries – through the provision of loans and technical

assistance – to introduce austerity measures in order to scale back fiscal costs. Measures

include subsidy reform, the means testing (or poverty targeting) of social security schemes,

labour market reform, and consumption tax increases.

3

However, many of these measures have

been criticised for having contributed towards rising poverty rates, reduced living costs, riots

and civil unrest.

4

Since the 2011 Arab uprisings, the IFIs have ostensibly tried to reduce these

negative impacts – for example, by promoting social security schemes as a means of mitigating

the effects of economic adjustment policies.

5

As such, the two IFIs have played a significant

role in shaping social protection and social security policy around the world: according to Kidd

(2018a), in 2017, almost 10 per cent of lending by the World Bank to low-income countries was

linked to social protection, while 10 per cent of IMF loans included conditions linked to such

schemes.

However, not all social security schemes are equally effective and, if badly designed, a

programme can be inadequate, poor performing, or even have negative impacts. Broadly, there

are two approaches to designing social security programmes. Under an inclusive lifecycle

approach, levels of investment are high due to broad coverage and high transfer values. States

are duty bearers obliged to provide a minimum social security floor, which addresses key risks

across the lifecycle, including old age, disability, childhood and unemployment. Schemes are

2

The term “social security” is used throughout the paper to refer to income transfers, regardless of how they are financed. While

“social protection” is the prevailing term that is used within the sector, the term “social security” is preferred by the author as it

aligns with the right to social security, as enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

3

International Labour Organization & World Bank (2016).

4

See, for example: Abdo (2019); Bretton Woods Project (2018, 2019); ESPI (2018).

5

Mossallem (2015).

1 Introduction

2

offered on a universal or near universal basis, since social security is an individual entitlement

– in other words, a human right (see Box 1).

In contrast, the IFIs promote a poor

relief package, in which schemes

have low budgets, low coverage, and

are targeted at households living in

poverty. Such schemes have an

ideological underpinning, supporting

a neo-liberal vision of low taxes and

a small State. Poor relief programmes

have been criticised for being too

small to reach all households living in

poverty.

6

As such, they are not able –

on their own – to address soaring

poverty rates and promote economic

growth.

Amid this criticism, the IMF and World Bank have signalled an ostensible paradigm shift in their

approach to social security. In 2016, the World Bank launched a global partnership with the

International Labour Organization (ILO) to promote universal social protection, with the World

Bank stating that: “Universal coverage and access to social protection are central to ending poverty

and boosting shared prosperity.”

7

Further, in 2018, the IMF Board detailed that “the IMF needs to

find more realistic and effective approaches to program design and conditionality to ensure that

adverse impacts of program measures on the most vulnerable are mitigated.”

8

A year later, the IMF

noted that it “does not have any bias in favour of one approach” with regard to universal or

targeted social security schemes, but that the “appropriate use of targeted and universal-type

transfers will depend on country economic, political, and social circumstances and constraints.”

9

This paper examines whether this paradigm shift has been observed within the MENA region, or

whether the social security packages that the IFIs promote are business as usual. It further

investigates whether the IFIs are putting in place the necessary building blocks to assist

countries in developing an inclusive, lifecycle social security system that will meet the IFIs’

supposed aim of achieving universal coverage, or whether the structures that are being pushed

will hinder the development of such systems. The paper also examines how the IFIs present

evidence and whether the language that is used is accurate, or whether it is designed to

confuse policymakers so that they are steered towards a particular ideological approach.

6

See, for example: Kidd, Athias, and Mohamud (2021).

7

International Labour Organization & World Bank (2016).

8

IMF (2018b).

9

IMF (2019).

Box 1: The right to social security in the Universal Declaration

of Human Rights

Article 22: “Everyone, as a member of society, has the right to

social security”

Article 25: “(1) Everyone has the right to a standard of living

adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his

family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and

necessary social services, and the right to security in the event

of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or

other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond his control. (2)

Motherhood and childhood are entitled to special care and

assistance. All children, whether born in or out of wedlock,

shall enjoy the same social protection.”

1 Introduction

3

Section 1 provides a brief overview of the context of the MENA region and its social security

systems. Section 2 then breaks down the components of the social security packages that the

two IFIs promote. Section 3 looks at the consequences of these packages, and Section 4 seeks

to explain why the IFIs promote the schemes that they do.

2 Context

4

2 Context

Although no two countries in the MENA region are the same, broad patterns can be drawn

between them. Across MENA States, there are widespread low incomes, high rates of informal

employment and high rates of inequality. Poverty rates, which have likely worsened during the

COVID-19 pandemic, are on the rise and, according to the World Bank, extreme poverty

increased from 3.8 per cent in 2015 to 7.2 per cent in 2018.

10

However, it should be emphasised

that a high proportion of the MENA population – not just those who have been classified as

living in extreme poverty – are living on low incomes.

11

For example, in 2018, around 45 per

cent of the population were living on less than USD 5.50 (PPP) per day.

12

In addition,

households fluctuate in and out of poverty, depending on the shocks that they experience. This

is exacerbated in countries experiencing conflict, such as Yemen and Iraq, or those in the midst

of a financial crisis, such as Lebanon. Indeed, because a household’s welfare can change

dramatically over a very short period of time, some have argued that “the poor” is a fictional

construct rather than a fixed group that could be identified at any given moment.

13

10

World Bank (2020a).

11

Extreme poverty is described, by the World Bank, as living on less than USD 1.90 per day (PPP).

12

Sibun (2021).

13

Knox-Vydmanov (2014).

2 Context

5

Figure 1: Depiction of the type of bifurcated social security system found in many low- and

middle-income countries

Source: Development Pathways’ depiction.

While social security is an important means of reducing inequality and lowering a country’s

poverty headcount, the systems in place across the MENA region are not fit for purpose. For the

upper segments of society, social insurance provisions are generally available, although in need

of reform. However, for those on low or middle incomes, or who are outside the formal

economy, often the only means of accessing social security is through a small, poor relief

scheme targeted at the poorest households. In Lebanon, for example, 6.5 per cent of the

population are receiving a tax-financed benefit and around a third are receiving a contributory

benefit.

14

As a result, many households living on low or middle incomes – which are still low –

or who have a household member working in the informal economy, are unable to access either

a social insurance scheme or a poor relief one. As Figure 1 indicates, this sector of the

population – which often forms the majority within a country – are the “missing middle”.

14

International Labour Organization & UNICEF (2021).

2 Context

6

Box 2: Subsidy reform is a fundamental part of the MENA context

Food and fuel subsidy reform accelerated in the 1990s, often with support from the IMF and the World Bank.

Reforms are generally extremely unpopular, resulting in protests and civil unrest. This unpopularity is due, in part,

to the fact that subsidies are often universal, or nearly universal, and their removal impacts on people across the

income spectrum, including more politically engaged families living on middle and high incomes, as well as those

working in the informal sector.

15

Given the opposition to subsidy reforms, the process has not been consistently implemented. For example, after

the 2011 uprisings, several countries scaled back their subsidy reforms including Jordan, Tunisia and Yemen, even

when the reforms were a requirement of the loans they received from the IFIs. Other countries, such as Egypt and

Morocco, have been more successful at implementing reforms, although Walsh and Boys (2020) explain that

these reforms excluded Liquid Petroleum Gas, which is more commonly used by the poorer segments of society.

Iran, meanwhile, successfully removed fuel subsides in 2011, by introducing a universal cash transfer programme

to compensate all citizens across the income spectrum.

In more recent years, subsidy reform has continued to be a major policy requirement of the IMF and the World

Bank. For example, Egypt’s recent fuel subsidy reform – which accelerated in 2014 – was supported both by the

World Bank and the IMF. For example, the World Bank provided technical assistance through the Energy Sector

Management Assistance Programme. Further, between 2016 and 2019, Egypt implemented a number of fiscal

reforms, including fuel subsidy reform, backed by a USD 12 billion IMF loan.

16

In Iraq, meanwhile, the IMF has

continually pushed for a reduction in Iraq’s food subsidy programme, the Public Distribution System, which, in

2021, was estimated to have 96 per cent coverage.

17

In 2017, the institution criticised the scheme for a “lack of

targeting, which leads to unnecessarily high outlays and an inequitable distributional impact.”

18

In the IMF’s 2020

Article IV report, the IMF stated that eligibility for the PDS should be limited and that the “authorities agreed with

the need to reform the PDS system and plan to take this up in the next stage of their reform agenda.”

19

Historically, the main form of tax-financed income support has been through the provision of

food

20

and fuel price subsidies, which are currently undergoing reform in a number of countries

across the region, as explained in

Box 2. Coverage of these systems was – and still is – high in

many countries and, as a result, subsidies have had a significant impact on poverty reduction. In

Egypt and Iraq, for example, Silva et al (2013) found that food ration cards reduced the poverty

headcount by more than 30 per cent. Although food subsidies are typically progressive because

poorer households tend to spend proportionately more on food, fuel subsidies

disproportionately benefit wealthier households and contribute to a large fiscal deficit. They

also divert States from investing in more effective systems, such as a tax-financed social

security scheme.

21

Nevertheless, they are often the only schemes that provide income security

15

See, for example, Sdralevich et al. (2014).

16

ESMAP (2019); IMF (2016).

17

Breisinger et al. (2021); Savage & Labs (2021).

18

IMF (2017a).

19

IMF (2021).

20

Food subsidies include a number of different types of subsidies, including ration-card system, subsidies on prices, subsidies on

production, etc. However, a separate analysis for each type is beyond the scope of the report.

21

Breisinger et al. (2019).

2 Context

7

to the “missing middle”. Over the last decades, many governments – with the support of the

IMF and the World Bank – have increased their attempts to phase out price subsidies. However,

unless price subsidies are replaced by compensation schemes with high coverage, subsidy

reform is generally extremely unpopular.

In a context where economic, social and

cultural rights are largely limited, the social

contract between citizens and the state is

considered by many to be absent or broken.

22

The historical importance of subsidies in the

region – as well as their universal, or near

universal coverage – has meant that subsidies

form an important element of an unwritten

social contract.

23

However, with subsidies being

scaled back, it is important that they are

replaced by social security schemes that are

sufficiently redistributive and effective to

develop and strengthen state-society relations.

24

22

Devereux (2015).

23

El-Katiri & Fattouh (2017). In addition, low salary competitiveness at the core of social/economic contract forcing the State to

maintain low prices for basic foods.

24

Kidd, S. et al. (2020).

Box 3: What is a social contract?

At a simple level, a social contract can be

understood as an agreement between citizens and

government. When it functions well, citizens and

residents pay taxes to the government and, in

return, the government should use these revenues

to provide good quality public services,

infrastructure and protection. As long as both sides

keep to the agreement, a functioning, decent and

fair society can exist. However, if governments do

not fulfil their side of the bargain, many will resent

paying taxes and, often, actively avoid doing so.

Taken from Kidd, S. et al (2020)

3 The World Bank and IMF’s Approach to Social Security

8

3 The World Bank and IMF’s Approach to Social

Security

The most significant means through which the IFIs impact on social security policy is via the

provision of loans to governments. Loans are often attached to conditionalities: in the case of

the World Bank, these are, for example, Performance Based Conditions (formerly called

Disbursement Linked Indicators) or Quantitative Performance Criteria and, for the IMF,

Structural Benchmarks. These conditions – which may specify, for example, that a country must

implement a social registry (a mechanism for undertaking poverty targeting – see Section 3.2)

– can be linked to disbursement. Therefore, if the condition is not met, disbursement, or a

tranche of the funds, may be withheld. As Kidd (2018a) notes, it can therefore be extremely

difficult for a government to change the design of a social security scheme if it does not align

with one of the conditions in the loan. He explains, for example that: “Mongolia was threatened

by the IMF and World Bank with the withholding of loans unless it targeted its popular universal

child benefit, with the government eventually acquiescing in January 2018.” Even in countries such

as Iran which do not receive loans, the impact of the IFIs should not be discounted: for

example, the IMF still holds considerable influence with regard to Article IV surveillance.

The IFIs also hold considerable influence over governments in terms of the paradigms that they

present to policy makers. For example, the World Bank supported a number of learning visits

for Iraqi government officials to other countries with poor relief schemes, with the intention of

persuading them to change the design of the Iraq Social Safety Net from one that targeted

demographic categories of the population living on low incomes, to one which identifies

households living in extreme poverty using a proxy means test (PMT), a form of poverty

targeting which is explained further in Section 3.2.

25

When promoting structural adjustment measures – especially subsidy reform – the IMF and

World Bank generally advise that part of the savings should be re-allocated to “well-targeted”,

“pro-poor”, “efficient” social security schemes. For example, in 2021, the IMF stated that poverty

targeting Iraq’s Public Distribution System Food Subsidy Programme “would provide the fiscal

space to further increase targeted assistance to the most vulnerable.”

26

However, the social security

schemes that are developed in the aftermath are generally much smaller than the subsidy

programmes that they are designed to replace. Indeed, Alston (2018), writing as the Special

Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty, states: “many subsidy reforms lead to significant net reductions in

social protection spending.” Consequently, the savings made in structural adjustment

25

Alkhoja et al. (2016). According to Alkhoja, the categories were orphans, married students, students that are orphans, those with

disabilities caused by ageing, those with disabilities caused by illness, the blind, the paralyzed, families of the imprisoned and

missing persons and the unemployed (e.g., due to terrorism and the internally displaced).

26

IMF (2021).

3 The World Bank and IMF’s Approach to Social Security

9

programmes are never fully diverted towards tax-financed social security schemes and other

social programmes.

The IFIs also aim to replace or redesign existing social security schemes. Existing tax-financed

schemes in the MENA region often identify people based on whether they are in a vulnerable

category of the population (for example, older persons, widows, families of prisoners) and

whether or not they have “any other means of support”. The latter was/is often defined

according to familial relations and whether someone would be deemed responsible for the

vulnerable person. These schemes are tweaked or replaced to better align with the social

security package that the IFIs promote.

Terminology is important, and the IFIs generally refer to their schemes as “social safety nets” or

“social assistance”, sometimes with the indication that lifecycle schemes are a different type of

social security to that proposed by the IFIs. This paper instead uses the term “social security”

both to refer to poor relief schemes as well as lifecycle programmes. This exemplifies the

difference between a poor relief paradigm and an inclusive lifecycle one. The former aims to

provide income security only to the most vulnerable, by catching them with a safety net,

whereas the latter adopts a human rights based approach, in which all persons – regardless of

their welfare level – are entitled to social security as a basic human right.

This section provides an overview of the components of the IFIs’ social security package. As is

demonstrated below, the package is neither as “pro-poor” nor “well-targeted” as they claim.

3.1 Low coverage

The schemes that the IFIs promote have small budgets, with low coverage. This means that

much of the “missing middle”, many of whom are living on low incomes, continue to lack access

to social security. For example:

• In a context of fuel subsidy reform, the World Bank is supporting the Government of

Tunisia to establish a new scheme called the Amen Social Programme which will

replace the Programme Nationale d’Aide aux Familles Necessiteuses (PNAFN). The

Permanent Cash Transfer (PCT) component of the scheme aims to increase coverage

from 8 to 10 per cent of the population. However, the poverty rate in Tunisia has

recently increased from 15 per cent to over 20 percent (and, it should be emphasised,

more than 20 per cent of the population are living on very low incomes). Further, an

additional 21 per cent of the population are identified as vulnerable and receive a

health card.

27

The entire “missing middle” would continue to be excluded, despite

experiencing significant shortfalls resulting from the fuel subsidy reform.

27

World Bank (2021b). See also Ben Braham et al. (Forthcoming) for a detailed discussion of Tunisia’s social security system.

3 The World Bank and IMF’s Approach to Social Security

10

• Under the World Bank’s “Jordan Emergency Cash Transfer COVID-19 Response Project”,

the IFI attached a Performance Based Condition to the loan, stipulating that by 2021,

85,000 eligible – i.e. “poor” – households would be enrolled in the Takaful Cash

Transfer Programme and would have been paid regular Takaful cash transfers (Takaful-

1). This amounts to between 4 and 6 per cent of the population.

28

UNESCWA (2021) has

noted that 270,000 households originally applied for Takaful, and around 108,000 were

found to be eligible. A further component, Takaful-3, is providing 160,000 households

with informal economy workers a cash transfer for a year, as part of the country’s

COVID-19 response. Again, these programmes exclude the missing middle.

• In Lebanon, under the World Bank’s “Lebanon Emergency Crisis and COVID-19

Response Social Safety Net Project”, an estimated 147,000 households – or only 12 per

cent of the population – will access the National Poverty Targeting Programme (NPTP)

and be paid cash transfers for one year.

29

However, in 2020, the World Bank

acknowledged that Lebanon’s current economic and financial crisis “could put more than

155,000 households under the extreme poverty line, but 356,000 households under the

upper poverty line.”

30

Even though poor relief schemes are too small to reach the majority of persons living on low

incomes, this issue is generally swept to one side by the IFIs. For example, the IMF has noted

that: “well-designed cash transfer systems in MENA can typically result in about 50–75 percent of

spending reaching the bottom 40 percent of the population, compared with 20 percent of the

amount spent to subsidize fuel prices and 35 percent to subsidize food prices.”

31

However, this fails

to recognise that more than the bottom 40 per cent of the population are vulnerable and

impacted by austerity measures, macroeconomic shocks and other lifecycle risks and

vulnerabilities. Further, as is discussed in Section 3.2, it also does not acknowledge that it is

impossible to accurately identify the poorest 40 per cent.

28

Based on a population estimate of 11 million, and an average household size of 4.8. Disparity in the figure given is due to

different average household sizes. The national average household size is 4.8, but according to the latest Household Expenditure

and Income Survey, the average individual in the poorest decile lives in a household of 7.7 persons. See also Anderson & Pop

(2022) for a detailed discussion of Jordan’s social security system.

29

World Bank (2021a). Prior to this, the NPTP paid in-kind benefits and fee waivers etc. The income transfer element is new. See

also Aboushady & Silva-Leander (Forthcoming) for a detailed discussion of Lebanon’s social security system.

30

World Bank (2020f).

31

Sdralevich et al. (2014).

3 The World Bank and IMF’s Approach to Social Security

11

Box 4: A case study of Egypt's Takaful and Karama Programme

Egypt’s Takaful and Karama Programme (TKP) was established in 2015 with support from the IMF and World Bank

and aimed to compensate those living in “extreme poverty” for austerity measures such as fuel subsidy reform.

However, Breisinger et al. (2018) found that the scheme was reaching only 20 per cent of the poorest quintile and

10 per cent of the second poorest quintile. This low coverage was especially notable, given that the World Bank

has found that 60 per cent of the population are poor and vulnerable.

32

Under the ‘Egypt Strengthening Social Safety Net” project, the World Bank is now supporting the government to

dissolve the Daman Social Pension and shift eligible beneficiaries over to TKP. The Daman social pension is a

means-tested unconditional monthly benefit paid to poor individuals and households, especially widows/divorced

persons, children with disabilities, orphans, and people younger than retirement age and unable to work due to a

disability. A Performance Based Condition stipulates that the government must “reassess beneficiaries of Daman for

the TKP using a [proxy means test]”. It is expected that many beneficiaries will not meet the requirements of the

TKP and will, therefore, no longer receive social security. As of September 2021, it was announced that TKP

would reach 3.9 million households, which amounts to around 15 million individuals (around 15 per cent of the

national population).

33

Coverage is, therefore, not broad enough to support the high number of people in need of

income security.

The IMF highlighted in its 2017 Article IV Consultation on Egypt that food subsidies had compensated for losses

brought about by fuel subsidy reform for the bottom 40 per cent, and half of the losses for the third and fourth

quintiles. This was attributed to the near universal design of the food subsidies. However, the IMF emphasised

that the food subsidy programme was “poorly targeted and inefficient” and that “improving targeting could free up

resources and reduce poverty among the low and middle income groups.”

34

Therefore, a scheme that is reaching the

majority of households living on low and middle incomes is described as being “poorly targeted”. Indeed, the IMF

also argued that TKP, in combination with other measures, “likely” fully compensated the effects of the reforms

for beneficiaries. The report failed to acknowledge that the majority of the population were not beneficiaries of

TKP and, therefore, the scheme could not have been effective.

An inclusive lifecycle scheme will always reach more persons living on low incomes than a

poor relief scheme due to its higher coverage. For example, Györi and Soares (2018) and Ben

Braham et al. (Forthcoming) have found that the introduction of a universal child benefit in

Tunisia would be much more effective at compensating a larger number of households that

have lost out on subsidies than the poverty-targeted schemes that were in place at the time.

Despite this, the IFIs’ messaging can confuse policy makers into thinking that poor relief

schemes are more “pro-poor”.

One example of how the IFIs use smoke and mirrors to give the impression that small poor

relief schemes are more effective at reaching the poor than universal schemes can be found in

Tunisia. As part of the broader Amen Social Programme, the Amen Social Family Allowance will

32

World Bank (2019c).

33

Zayed (2021).

34

IMF (2018a).

3 The World Bank and IMF’s Approach to Social Security

12

provide cash transfers to 120,000 children aged 0-5 years registered on the social registry

(around 10 per cent of that age group).

35

In a Project Appraisal Document, the World Bank

states that “simulations show that the share of beneficiaries of a family allowance programme in the

first decile should be about 30 per cent, and larger than any other subsidy program” and provides

the following information:

Table 1: Incidence of Different Social Protection Interventions in Tunisia

D1

D2

D3

D4

D5

D6

D7

D8

D9

D10

Energy Subsidies

6.1

7.4

8.0

8.6

9.2

9.7

10.3

11.5

12.8

16.4

Food Subsidies

8.7

9.6

9.7

10

10.2

10.3

10.4

10.5

10.5

10.0

Children 0—5 years whose

parents are not enrolled on a

contributory programme

29.6

17.3

13.6

11.6

8.6

6.4

5.5

3.8

2.5

1.4

Source: Based on World Bank (2021b).

The table is misleading, for two reasons. Firstly, the table is not actually showing the

distribution of Family Allowance beneficiaries, as claimed in the Project Appraisal Document

claims; rather, it shows the beneficiaries of a very different type of potential scheme in Tunisia.

This alternative programme is a child benefit that would be given to children aged 0-5 years

whose parents are not receiving a family benefit from the social insurance system (referred to

as a benefit-tested child benefit). In effect, therefore, the World Bank provides no evidence on

the Amen Social Family Allowance, despite claiming that it would be well-targeted. Instead it

uses simulated data for a much larger, but different type of programme, as a proxy for the

Family Allowance in its attempt to demonstrate that the Family Allowance is well-targeted. Yet,

the Family Allowance only covers 120,000 children, whereas the benefit-tested child benefit

cited in the Project Appraisal Document would have reached around 383,000 children in

2022.

36

The World Bank also confuses the reader by using “benefit incidence” to measure the

effectiveness of targeting. This methodology is commonly used by the World Bank as it almost

always gives the impression that means-tested programmes are “better targeted” than universal

schemes. The methodology examines the distribution of all recipients of a scheme across the

welfare profile of the population. Using this measure makes the benefit-tested child benefit

look much better than the universal food subsidy. In fact, it makes the food subsidy appear

regressive while the benefit-tested child benefit seems, to the uncritical eye, to be more “pro-

poor”.

However, if the schemes were assessed using a more appropriate measure that examines their

effectiveness in achieving the aim of reaching the poorest members of society, the universal

35

UNDESA population estimates for 2022.

36

CRES & UNICEF (2019).

3 The World Bank and IMF’s Approach to Social Security

13

food subsidy is much more effective. It would reach many more families in the poorest deciles

than the simulated benefit-tested child benefit (and many more than the World Bank-supported

Amen Social Family Allowance). In addition, the food subsidy would also reach struggling

families on middle – but still low and insecure – incomes. In effect, therefore, by reaching

many more families living in poverty, the food subsidy would be much more “pro-poor” than

both the Amen Social Family Allowance and a “benefit-tested” child benefit for those children

whose parents are not enrolled on a contributory programme, which is the type of programme

simulated in the study they cite. The Family Allowance promoted by the World Bank would

cover only 120,000 children, whereas the latter would cover around 383,000 children in 2022.

37

Consequently, the impacts of the Family Allowance would be much smaller than indicated.

The same point is illustrated in Figure 1, which compares the potential targeting effectiveness

of a benefit-tested child benefit with a universal child benefit (the type of scheme that the

World Bank conventionally opposes). The lines – which use the scale on the right – show

“targeting effectiveness” when employing the World Bank’s preferred benefit incidence

methodology. The benefit-tested child benefit – used by the World Bank as a proxy for the

Family Allowance – appears much better targeted than the universal child benefit. But, when

using the alternative – and more appropriate – measure of the schemes’ effectiveness in

reaching children in the poorest deciles, the universal benefit appears much more effective. As

the bars – which use the left-hand scale – in Figure 1 show, many more children in the poorest

deciles would be reached by the universal child benefit, making its targeting far superior to the

benefit-tested scheme. For example, while the benefit-tested child benefit would reach only

113,000 children in the poorest decile, this number would be far surpassed by a universal child

benefit, which would reach 172,000 children. Given that the benefit-tested child benefit is only

a proxy for the much smaller Amen Social Family Allowance, the universal child benefit would

be even more effective in reaching the poorest children than the Family Allowance, which

would reach only 120,000 children in total.

In effect, therefore, the World Bank’s presentation of the data on targeting effectiveness is a

classic example of how a magician uses smokes and mirrors to confuse its audience.

37

CRES & UNICEF (2019).

3 The World Bank and IMF’s Approach to Social Security

14

Figure 1: Incidence versus Absolute Numbers for beneficiaries of child benefits in Tunisia

(2022).

Source: Estimates for the universal child benefit are based on the National Survey on Household Budget, Consumption and

Standard of Living and population projections for 2022 from the UNDESA World Population Prospects 2019 revision. Estimates for

the programme cited by the World Bank in its Project Appraisal Document (for the benefit-tested child benefit) children whose

parents are not enrolled on the contributory programme) are taken from CRES & UNICEF (2019).

Meanwhile, in Morocco, the World Bank argued that the government’s planned universal child

benefit is “likely to be progressive” but contrasted it with a poverty-targeted scheme with 40 per

cent coverage, which the Bank says would be “even more progressive.”

38

The use of the word

“progressive” is misleading, as it could push policy makers towards thinking that the scheme

with low coverage is more likely to reach people living on low incomes, when, in fact, the

opposite is true, due to the likely very high targeting errors, which would result from the

poverty-targeted option.

39

38

World Bank (2020c).

39

Kidd and Athias (2020).

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

0

20,000

40,000

60,000

80,000

100,000

120,000

140,000

160,000

180,000

200,000

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

Distribution of children covered

Absolute number of children

Welfare deciles

Number of children 0-5 covered by the (benefit-tested) programme cited by the World Bank

Number of children 0-5 covered by a universal child benefit

Distribution of children 0-5 covered by the (benefit-tested) programme cited by the World Bank

Distribution of children 0-5 covered by a universal child benefit

3 The World Bank and IMF’s Approach to Social Security

15

3.2 Poverty targeting

In order to implement a scheme with low coverage, the IFIs use poverty targeting as a means of

identifying the poorest members of the population. In the MENA region, a PMT has been

employed, for example, in Morocco, Algeria, Jordan, Egypt, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia,

Palestine, Tunisia, Yemen and Lebanon.

40

A PMT utilises a household survey to develop a

number of proxies to statistically predict a household’s income. In order to promote its use, the

targeting mechanism may become a condition in the loan. In Egypt, for example, a

Disbursement Linked Indicator specifying that a PMT would be designed and used to identify

beneficiaries was incorporated into the “Egypt Strengthening Social Safety Net” Project.

41

In

addition, the following Project Development Objects were applied:

• 60 per cent of the programme’s beneficiaries are under the poverty line

• 20 per cent of poor households are covered by the programme.

The World Bank has promoted this method as a “scientific” mechanism,

42

which it describes as

efficient and accurate. However, in reality it is a highly inaccurate process, with selection often

being little more than random. This is exemplified through the analysis of exclusion errors,

which shows the proportion of intended recipients that are excluded from a scheme. For

example, Egypt’s TKP has been found to have an exclusion error of 55 per cent for the poorest

quintile and 75 per cent for the second quintile.

43

In addition, in a global review conducted by

Development Pathways, it was found that utilising a PMT results in exclusion errors ranging

from 46 per cent to 96 per cent.

44

Poverty targeting is inaccurate for a number of reasons. Firstly, when the majority of persons

are living on low incomes, it can be difficult to differentiate among them. This is especially the

case when household composition, income and consumption levels fluctuate over a short

period of time. Consequently, a household may belong to the poorest group of the population

at the beginning of the year, but could have moved out of it by the end. The situation is only

heightened in countries experiencing financial crises, war, conflict and other shocks, as many in

the MENA region are. As Kidd et al. (2017) explain: “Many of those households that may have

been ‘correctly targeted’ in the first year are likely to be ‘inclusion errors’ in future years, as a result

of improved circumstances. However, anyone falling into poverty between surveys – perhaps due to

a crisis such as unemployment or the death of a breadwinner – is excluded from accessing social

security, until the time comes to be reassessed.”

40

World Bank (2020f).

41

World Bank (2015a).

42

World Bank (2020f).

43

Breisinger et al. (2018).

44

Kidd & Athias (2020). For schemes targeting the poorest 25 per cent of their intended category or less.

3 The World Bank and IMF’s Approach to Social Security

16

Second, for a PMT to be accurate, it must utilise up-to-date data. This means that it is essential

that a country is not only in a situation in which it can update its household surveys, but that it

has sufficient human resources to keep the data current. The IFIs are aware of this limitation:

the World Bank has stated that “even accurate models will be undermined if PMT implementation

is poor; for example, if household registry data are incomplete or out of date, or an incorrect scoring

threshold is applied.”

45

Despite this, it continues to promote PMTs in countries where the

mechanism is wholly unsuitable. For example, in 2017, the IMF wrote that the long-term

success of the PMT in Iraq will “depend on local capacity to regularly assess and revise, as

necessary, the targeting criteria. It is also crucial to enlarge the network of social workers to improve

control over eligibility and uptake, as well as to ensure access and accommodate on-site visits and

assessments.”

46

However, Tull (2018) has noted that the PMT entailed a number of challenges

including putting together a cadre of social workers and undertaking case management in

liberated areas.

In Yemen, meanwhile, no improvements have been made to the PMT in a decade due to the

ongoing conflict. The World Bank notes that “under normal circumstances, the PMT would have

been revised based on a new households survey, existing beneficiaries recertified, and new

households added to the beneficiary list. However, the current conflict makes this option not feasible

from a technical and political perspective.” Nevertheless, it maintains that Social Welfare Fund

beneficiaries “are likely to remain among the poorest in the country.”

47

There is no means of

knowing whether this is actually accurate, and so the World Bank is making a potentially

incorrect claim about the effectiveness of the PMT. However, given that, in 2019, around 75 per

cent of the population was living on less than US$3.10 a day,

48

it is evident that the majority of

persons living on low incomes are not being reached due to the scheme’s low coverage.

The third reason why poverty targeting results in high exclusion errors is the fact that PMTs are

not an accurate indicator of wealth. For example, in many formulae, households are

automatically excluded if they own a car.

49

Consequently, a household may not qualify for the

scheme even if they own a vehicle that is broken or which they cannot afford to fix because

they have no household income. Global evidence also points to PMTs encouraging perverse

incentives, such as households falsifying their answers in order to be enrolled. Indeed, in an

evaluation Egypt’s TKP scheme, it was noted that, although the PMT formula was secret,

households could make educated guesses about what was included, and there was room for

wealthier households to under-report their assets.

50

45

World Bank (2018).

46

IMF (2017a).

47

World Bank (2020b).

48

Moyer et al. (2019).

49

United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (2021).

50

United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (2021).

3 The World Bank and IMF’s Approach to Social Security

17

Due to the inaccuracy of the PMT mechanism, the IFIs invest a lot of money trying to improve

the targeting formula. In Tunisia, for example, a Performance Based Condition stipulates that

the PMT formula used under the Amen Social Programme needs to be updated.

51

Meanwhile, in

Jordan, a Performance Based Condition attached to the “Emergency Cash Transfer Response

Project” loan requires the National Aid Fund (NAF) to develop “a revised Takaful targeting

methodology based on the findings of the evaluation study and [for it to be] approve[d] by its Board

of Directors.” Further, the NAF will provide “the Bank with the revised targeting formula that is

satisfactory to the Bank team based on the findings of the targeting evaluation. This will be

validated by the World Bank.”

52

In Iraq, the World Bank attempted to reformulate the PMT

formula to address issues of high displacement. In order to reduce inclusion errors, the IFI

suggested using community-based targeting alongside a PMT.

53

However, community-based

targeting is also a highly inaccurate targeting mechanism, and schemes that use this

mechanism, combined with a PMT, still have high exclusion errors. Kidd et al found that

Kenya’s Hunger Safety Net Programme, for example, which uses a combination of methods

including community-based targeting, has an exclusion error of 70 per cent.

54

Further, there is

no evidence that PMTs can be meaningfully improved, as errors are consistently high globally.

55

As discussed in Section 3.1, despite widespread evidence showing that poverty targeting is

inaccurate, the IFIs continue to use smoke and mirrors to mislead policy makers into thinking

that this is not the case. For example, the World Bank states, that out of the current 150,000

households who are on Lebanon’s National Poverty Targeting Programme (NPTP) database,

43,000 households have PMT scores corresponding to the extreme poverty threshold, which

“suggests a very good identification of potential beneficiaries, in line with the best performing social

assistance programs.” There is little acknowledgement, however, of how inaccurate PMTs can be

and that a well performing PMT is, objectively, performing very poorly.

56

Elsewhere in the

document, the World Bank does recognise that an assessment of targeting performance is not

currently possible due to “the small scale of targeted safety net coverage and the absence of recent

nationally representative household survey data.”

57

It is, therefore, difficult to understand how the

World Bank can know that there has been “a very good identification of potential beneficiaries.”

Indeed, the PMT formula is based on a household survey that was carried out in 2011. It is

therefore completely inaccurate and not remotely reflective of Lebanon’s current financial

situation.

51

World Bank (2021b).

52

World Bank (2020e).

53

World Bank (2018).

54

Kidd & Athias (2020).

55

Kidd & Athias (2020).

56

Aside from a note that smaller families may not be identified “because of the household characteristics used by the targeting

mechanism to calculate household poverty”, that some regions are under-represented in the database, and that other families may

miss out due to access barriers.

57

World Bank (2020d).

3 The World Bank and IMF’s Approach to Social Security

18

When assessing the impacts of a poverty-targeted programme, the World Bank and IMF often

do not account for the exclusion errors that are a result of the design of the targeting