IELTS

Writing:

Grammar and Vocabulary

Erica L. Meltzer

New York | Vancouver

®

Copyright © 2021 The Critical Reader Publishing

Cover © 2021 Tugboat Design

All rights reserv

ed.

No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical,

including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without written

permission from the author.

For information regarding bulk purchases, reprints, and foreign distribution and rights, please send

correspondence to [email protected].

IELTS

®

is a recognized trademark of the British Council and IDP Australia, which are unaffiliated with

and do not endorse this product.

ISBN-13: 978-1-7335895-7-4

ALSO BY ERICA L. MELTZER

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

The Ultimate Guide to SAT

®

Grammar & Workbook

SAT

®

Vocabulary: A New Approach (with Larry Krieger)

The Critical Reader: The Complete Guide to SAT

®

Reading

The Critical Reader: AP

®

English Language and Composition Edition

The Critical Reader: AP

®

English Literature and Composition Edition

The Complete Guide to ACT

®

English

The Complete Guide to ACT

®

Reading

GRE

®

Vocabulary in Practice

The Complete GMAT

®

Sentence Correction Guide

How to Write for Class: A Student’s Guide to Grammar, Punctuation, and Style

Table of Contents

Introduction . . . 9

A Note About the English in this Guide . . . 13

IELTS Writing Cheat Sheet . . . 14

Parts of Speech . . . 18

Basic Conventions and Punctuation

1. Paragraphs . . . 24

2. Capitalization and Spacing . . . 24

3. Apostrophes . . . 26

4. Numbers . . . 27

5. Register: Formal vs Informal . . . 28

Definite and Indefinite Articles

6. Articles with Singular Nouns . . . 40

7. Articles with Plural Nouns . . . 45

8. Articles with Geographic Locations . . . 49

9. Articles with Nationalities . . . 50

Sentence Construction

10. Elements of a Sentence . . . 52

11. Conjunctions and Sentence Types . . . 56

12. Comma Splices with Pronouns . . . 60

13. Dependent Clauses: Verbs and Punctuation . . . 62

14. Preposition + Which . . . 65

15. Too Many Clauses . . . 66

16. Parallel Structure . . . 67

v

Verb Forms, Tenses, and Modes

17. Tense Consistency . . . 72

18. Present Tense: Simple vs. Continuous . . . 73

19. Present vs. Future vs. Conditional . . . 74

20. Present Perfect vs. Simple Past . . . 76

21. Past Continuous . . . 81

22. Past Perfect . . . 82

23. Past Conditional . . . 83

24. Future Perfect . . . 83

25. Sequence of Tenses: Conditionals . . . 84

26. Sequence of Tenses: Indirect Speech . . . 85

• Common Irregular Verbs: Principal Parts . . . 87

27. Modal Verb + Bare Infinitive Only . . . 88

28. Direct Questions . . . 89

29. Passive Voice . . . 90

Subject-Verb Agreement

30. Third-Person Singular vs. Plural . . . 94

31. Agreement with Indefinite Pronouns . . . 99

Pronouns and Nouns

32. Omitted and Unnecessary Pronouns . . . 102

33. Agreement with It and They . . . 103

34. Additional Pronouns . . . 106

35. Noun Agreement . . . 109

36. Reflexive Pronouns . . . 110

37. People vs. Things . . . 112

38. Commas with That, Which, and Who . . . 116

39. Indirect Questions . . . 118

vi

Modifiers

40. Adjective Placement . . . 122

41. Order of Adjectives . . . 124

42. Compound Adjectives (Hyphens) . . . 124

43. "Trick" Nouns as Adjectives . . . 125

44. -ING vs. -ED as Adjectives . . . 126

45. Comparatives and Superlatives . . . 127

46. Comparing Amounts . . . 130

47. Adverb Placement . . . 134

48. Adverbs of Degree . . . 136

49. Commonly Confused Adjectives and Adverbs . . .137

50. Dangling and Misplaced Modifiers . . . 140

Essay- and Letter Writing Tips

51. Using Transitions Effectively . . . 142

52. Letter-Writing Conventions . . . 148

53. Writing About Graph(ic)s . . . 151

54. Task 2 Introduction and Conclusion . . . 172

55. Presenting Opinions . . . 174

56. How Much Should You Explain? . . . 178

Vocabulary

57. Using Vocabulary Appropriately . . . 182

58.Increasing and Decreasing . . . 187

59. Younger and Older People . . . 191

60. Describing Your Education . . . 193

61. Describing Types of Work . . . 194

62. Talking, Speaking, and Discussing . . . 196

63. Requests and Recommendations . . . 199

64.Giving Permission (The Causative) . . . 200

65.Commonly Over- and Misused Words . . . 201

66. Commonly Confused / Misspelled Words . . . 205

67. Tricky Uncountable Nouns . . . 208

vii

Prepositions and Collocations

68. Top Preposition-Based Expressions . . . 210

69. Verbs with Infinitives and Gerunds . . . 213

70. Expressions with Make, Do, and Get . . . 214

Appendix: Common Terms by Category

• Arts and Entertainment . . . 216

• Business and Economy . . . 216

• Cities and Transport . . . 217

• Diet, Health, and Fitness. . . 217

• Education . . . 218

• Environment . . . 218

• Family . . . 219

• Government and Politics . . . 219

• Housing . . . 219

• Legal . . . 220

• Media . . . 220

• Technology . . . 221

• Travel . . . 221

• Covid-19 . . . 222

About the Author . . . 223

viii

Introduction

This is not a traditional grammar book, nor is it a comprehensive one. It concentrates

exclusively on common areas of difficulty for IELTS® candidates, based on an analysis

of more than a hundred essays by writers scoring primarily in Bands 6 and 6.5. However,

it also covers many topics that even advanced English-language learners (and, for that

matter, some native speakers) find challenging, and you are likely to find some value in it

even if you are already scoring at Band 7 or above. This guide also places a heavy

emphasis on contemporary idiomatic usage: it covers constructions that you may never

have encountered in a classroom but that are frequently used by native anglophones.

And while it does use grammatical terminology as necessary, its focus is always on

practical application: grammatical principles are continually and explicitly illustrated in the

types of sentences required throughout Task 1 and Task 2 responses (both Academic

and General Training).

IELTS Writing has a reputation as the most unforgiving of the exam’s four sections, and

deservedly so: according to the demographic statistics provided by the British Council

1

,

average scores in Writing are lower than those in the other three sections in virtually every

country, and often run nearly a full band lower than scores in Listening, Reading, and

Speaking. This holds true for test-takers from every country and native language,

including English. (Note that the mean band score in Writing is a mere 6.2 for native

English speakers in Academic Training, and 6.5 in General Training.)

Given the size and consistency of this gap, it is not a surprise that myths and

misconceptions about the Writing section abound. It is not uncommon to hear students

who have repeatedly fallen short of their target Writing score claim that the IELTS is a

scam and that examiners deliberately deflate scores in order to force students to pay for

repeated examinations. To be absolutely fair, there is always an element of subjectivity

involved in essay grading, and some Enquiries on Results do in fact result in Writing

scores being revised upwards. But that said, having read an enormous number of essays

by students who have received band scores of 6 or 6.5, I can also attest to the fact that

responses in Band 6 (B2 level, or upper-intermediate) generally receive that score for

good reason, and that for many candidates, moving up to Band 7 (C1 level, or lower-

advanced) represents a very significant challenge indeed. It is not a matter of learning a

few simple tricks, or of sprinkling in a few “high-level” words such

as plethora and aforementioned. Rather, it is the difference between writing with English

words and writing in English. Essays that score Band 7+ may contain isolated errors in

grammar or vocabulary, but the overall structure of the language is solid.

9

The most important thing to understand about IELTS Writing is that you are being

assessed on your ability to use standard written English as a vehicle for your ideas.

The question is not whether you know how to use a particular set of high-level or

“complex” constructions but rather whether you are able to select the structures

and vocabulary most appropriate for expressing thoughts relevant to the question

at hand, and to use those features of English accurately.

One of the more serious misunderstandings about IELTS essays stems from the Band-7

requirement for “complex” sentences. Contrary to what many candidates believe, this

does not imply that essays need to be packed with complicated constructions; it merely

means that some sentences must include different types of clauses. (For

example, Although zoos play an important role in preserving endangered species, I

believe that animals should remain in the wild is a complex sentence.) Likewise, "less

common vocabulary" refers to subject-specific terms (for example green energy, net-zero

emissions, and carbon neutral in an essay about environmental issues) rather than to

rarely used words such as salubrious.

The other, exceedingly important issue that many IELTS candidates are often unaware

of is the importance of adhering to the conventions and niceties of standard written

English. If you are accustomed to using English primarily for gaming or posting on Internet

forums, and have limited experience writing in more formal situations, you may not realize

the importance of elements such as capital letters and spacing. For example, placing a

comma immediately after a word and leaving exactly one space before the next

word, every single time, is a fundamental part of writing correctly in English—you cannot

randomly add or omit spaces. This is true not only for the IELTS but for any academic or

professional situation in which you might find yourself. To put it bluntly, you cannot obtain

a high Writing score if your prose looks as if it were produced by an Internet bot!

The good news is that once English learners reach an upper-intermediate level, most of

their difficulties tend to be concentrated in a limited number of areas. The bad news,

however, is that these areas involve some of the most common constructions in the entire

English language (for example, definite and indefinite articles). As a result, mistakes

involving them are typically not restricted to isolated phrases; rather, they appear

throughout a response and thus have a disproportionate effect on the overall score. In

order to fix misunderstandings in these areas, you must first become aware of them.

Officially, “Grammar” is only one of the four categories in which Writing responses are

assessed, the others being “Lexical Resource” (vocabulary); “Coherence and Cohesion”;

and “Task Achievement” (Task 1) or “Task Response (Task 2). In reality, however, there

10

is considerable overlap among these areas, and grammar is the foundation on which your

ability to express yourself clearly and convincingly rests. Simply put, essays are made up

of sentences, and so you cannot write a coherent essay in English unless you can

write a coherent sentence in English. Writing that contains flaws at a basic structural

level prevents you from conveying your ideas with precision, which in turn impedes your

ability to stay on task as well as develop your answers in ways that directly support your

arguments. In the worst case, you may accidentally imply the opposite of your intended

meaning.

Moreover, aspects of the non-grammar categories involve grammar, both directly and

indirectly: your skill at linking nouns and pronouns, for instance, is factored into your

Coherence and Cohesion score. And any attempt at using sophisticated vocabulary or

idioms / collocations will almost certainly backfire if the words or phrases appear within a

sentence that reads as if it were translated directly from another language.

So while this guide does include some longer sample passages, the focus here is on the

details of constructing accurate and idiomatic statements at the sentence level. For full-

length essays, there are a number of websites run by native English speakers (some of

whom are former examiners) that provide excellent examples of model high-scoring

answers: these include www.ieltsetc.com, www.ieltsliz.com, www.ielts-simon.com, and

www.ted-ielts.com.

When you read sample high-band essays, notice that the writers maintain a generally

straightforward style and do not try too hard to make their writing seem original or poetic.

IELTS candidates are frequently warned that they should not attempt to learn answers by

heart, and this is of course excellent advice—memorizing a series of phrases, or even an

entire essay, on a given topic and then attempting to “twist” it to fit a question on an

unrelated subject is an extraordinarily bad idea, and under no circumstances should it be

encouraged. That said, standard written English relies on many conventions and idiomatic

phrasings that must be learned word-for-word, and that sound obviously wrong when

altered. However, when students are not made aware of this fact, they may attempt to

“improve” on standard formulations in an attempt to sound more original, and as a result

form wildly unidiomatic constructions. This is particularly common with linking devices

(transitional words and phrases). For example, a student may write on the dark

side instead of the standard on the other hand. Unfortunately, this is precisely the

opposite of what is required to achieve a high score: according to the IELTS band

descriptors, a Band 9 essay is one that “uses cohesion in such a way that it attracts no

attention”.

11

Likewise, the word “formal” is responsible for many misconceptions about what sort of

language the Task 2 essay involves. In reality, it is more accurately described as a “semi-

formal” or “moderately formal” essay; the most formal kind of English—the kind found in

legal documents, for example—is not expected. But when these definitions are not

explained, students may assume that they need to fill every sentence with overblown

language and obscure vocabulary (often improperly used), a practice that results in prose

that is at best stiff and excessively formal, and at worst barely comprehensible.

In reality, achieving a Band 7+ Writing score is both easier and harder than many

IELTS candidates realize. It is easier in the sense that it is perfectly possible to score

well using mainstream, relatively common vocabulary and one- and two-clause

sentences, with an occasional longer one thrown in for variety. However, it is also more

challenging in the sense that those basics need to be done correctly—and by definition,

writing at an “advanced” level means getting most things right. There is some room for

error, of course, but less than what many people imagine; range cannot compensate for

too many problems in accuracy. Even a test-taker whose writing contains only “very

occasional errors or inappropriacies” will receive a score no higher than 8 in Grammar.

So while some of the points covered in this guide may seem minor or overly picky, they

are in fact designed to target the types of errors that, taken together, can rapidly cause a

Grammar score to drop to Band 6 or lower.

It is also important to recognize that there is no way to hide or compensate for basic

misunderstandings with fancy vocabulary, or idioms, or even just good ideas. Examiners

know all the tricks, and they won’t be fooled. So although it may seem counterintuitive,

making the necessary progress is likely to require taking a step back and 1) discovering

where your trouble spots lie, and 2) getting solid on the fundamentals that you never quite

mastered. That’s where this book comes in. Although this approach can be tedious, it is

far more constructive than churning out lots of full-length responses with the same

mistakes made over and over again. In the long term, taking the time to build a solid

foundation is much more likely to get you where you want to go.

–Erica Meltzer

12

A Note About the English in this Guide

Although the IELTS exam is administered by the British Council, it is intended for an

international audience, and you are free to use whatever form of English you are

accustomed to; there is no penalty for using American spellings. The only requirement is

that you be consistent, e.g., if you write colour, you should not then write neighbor. You

are free to mix vocabulary, as anglophones often do. The major differences are as follows:

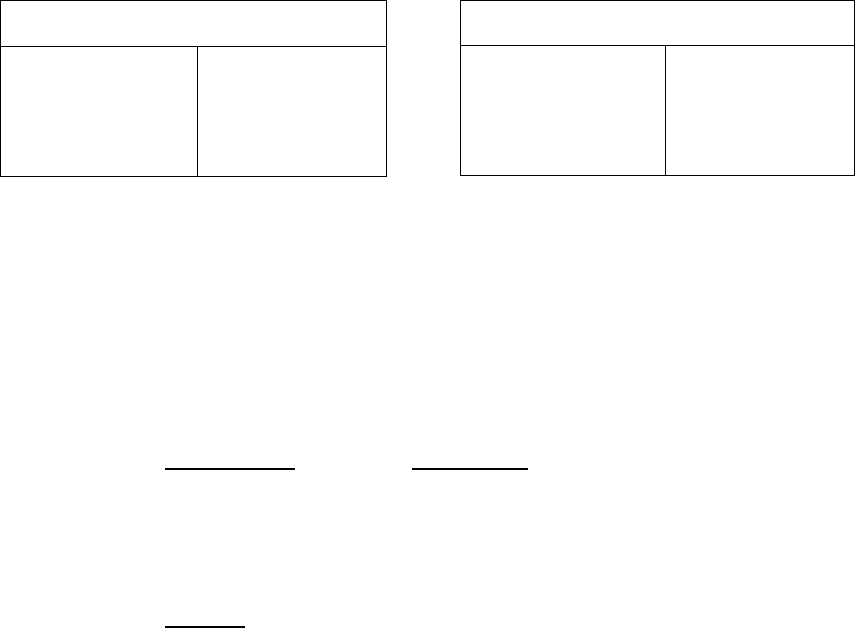

British Commonwealth (Br.)

United States (Am.)

• -i / -yse (emphasise, analyse)

• -our (colour, neighbour)

• -l and -s endings doubled before

a suffix, e.g., traveller, focusses

• learnt, burnt

• centre, theatre, litre

• offence, defence

• programme

• practise (v.; practice, n.)

• cheque

• -i / -yze (emphasize, analyze)

• -or (color, neighbor)

• -l and -s endings not doubled before

a suffix, e.g., traveler, focuses

• learned, burned

• center, theater, liter

• offense, defense

• program*

• practice (n., v.)

• check

*also used in Canada and Australia

This guide addresses the UK/US divide by following Canadian conventions: US-style

-ize and -yze endings are used for words such as analyze and globalization, whereas

British Commonwealth spellings are followed for other words. This choice is designed to

reflect the international nature of the exam, as well as the fact that IELTS candidates

intend to live in anglophone countries with a variety of linguistic conventions.

The examples in this guide—like IELTS essay questions—are intended to be as broad

and general as possible, focusing on topics in which differences between various types

of English are essentially irrelevant. Unless you are already communicating at a near-

native level, you do not need to worry about regional terms or minor stylistic issues. Your

primary concern should be learning to construct clear, coherent sentences that can be

easily understood in everyday professional and academic contexts.

13

IELTS Writing Cheat Sheet

1. Standard spacing: full stops / periods, commas, and semicolons are placed right

after a word, with one space before the following word.

2. Always capitalize the first word in a sentence; the pronoun I; and the names of

specific people, places, and things (e.g., Robert, Mexico, Infosys).

3. Contractions (e.g., don’t, wasn't) = informal; use only in Task 1 GT letters to

friends. Do not ever use slang (e.g., gonna, wanna) or textspeak (e.g., u for you).

4. A(n) = indefinite, indicates a noun in general or one of many; often used when a

noun is first mentioned.

The = definite, indicates the only one; used with superlatives (e.g., the best way);

with first, second, etc. + noun (e.g., the first time) and often when a noun is

mentioned again.

5. Articles and indefinite pronouns: Few = almost no (one); A few = several;

The majority; A number of (=many).

6. Focus on correct usage rather than obscure or "high-level" words; when

paraphrasing, use synonyms whose meanings you are absolutely certain of.

7. Linking devices = formulas; do not alter phrases such as on the other hand in an

attempt to sound more original.

8. Two sentences must be separated by a full stop / period, NOT a comma. This is a

common issue when a conjunctive adverb (e.g., however, therefore, in fact) begins a

clause, or the subject is a pronoun rather than a noun (e.g., it has increased).

9. Two consecutive clauses should not both begin with a coordinating

conjunction (e.g., and, but, so) or a subordinating conjunction (e.g., although, while, as).

10. Modal verb + bare infinitive (e.g., can make), NOT conjugated verb or past tense

(e.g., can to make or can made). Exception: ought + infinitive.

11. Request, recommend, and suggest + (that) + subject + bare infinitive (e.g., She

suggested (that) I restart the laptop, NOT She suggested me to restart the laptop).

14

12. Present perfect: since + starting time (e.g. I have studied English since 2011);

for + duration (e.g., I have studied English for 10 years).

13. Simple past (e.g., went) = finished action, used with a date or time; Past perfect

(e.g., had gone) = finished action that came before a second action.

14. Will = future; Would = hypothetical actions or polite form, used for requests.

15. When or if + present tense (e.g., When I go to Canada), not future tense.

16. 3rd-person singular verbs end in -s (e.g., it increases); 3rd-person plural verbs do

not end in -s (e.g., they increase).

17. One + sing. noun (e.g., one effect); One of the + pl. noun (e.g., one of the effects).

18. Singular noun = it(s) or it's (= it is); Plural noun = they.

19. That: no comma before or after.

20. Indirect questions: use a full stop / period, NOT a question mark; verb follows subject

(e.g., I don’t know why the package hasn’t arrived yet).

21. Nouns acting as modifiers are never made plural (e.g., One of my favourite dishes

is lentil soup, NOT One of my favourite dishes is lentils soup.)

22. Comparatives and Superlatives: 1-syllable adjective & 2-syllable adjective ending

in -y: -er / -est (e.g., harder, funniest). All others = more / most + adjective (e.g., more

careful, most important).

23. Uncountable: advice, furniture, information, infrastructure, research.

24. Many, fewer modify countable nouns; much, less modify uncountable nouns.

25. Prepositions/Idioms:

• I’m looking forward to + -ing form (e.g., I’m looking forward to going to London).

• Use on + day OR next + day (e.g., I'll do it on Tuesday, OR I’ll do it next Tuesday),

NOT on next + day (e.g., I’ll do it on next Tuesday).

• Considered (to be) + noun (e.g., He is considered (to be) one of the greatest

football players, NOT He is considered as one of the greatest football players).

15

16

Parts of

Speech

1

7

Verbs

Verbs indicate actions (e.g., to play, to work, to believe) and states of being (e.g., to be, to

become, to seem, to appear).

The "to" form of a verb is called the infinitive. An infinitive without the word to is called

the bare infinitive.

When a verb follows a subject (noun or pronoun), it must be conjugated. In most cases,

this simply involves removing the to; however, when the subject is a third-person singular

(pro)noun, an -s is added to the end of the verb (e.g., it increases).

To be and to have are the most common English verbs. You must be able to conjugate

them correctly and recognize their present and past forms.

To have: I, you, we, they have; s/he, it, one, has.

The past tense of have is had, invariable.

Transitive verbs must be followed be a noun or pronoun (direct object).

Correct: An increasing number of young people spend hours playing

video games or surfing the Internet every day.

Intransitive verbs are followed by preposition + noun (indirect object).

Correct: An increasing number of young people spend hours looking at

screens every day.

To Be, Present

I am

You are

S/he, It, One is

We are

You (pl.) are

They are

To Be, Past

I was

You were

S/he, It, One was

We were

You were

They were

18

Nouns

Nouns indicate people, places, and things.

Most plural nouns add -s at the end (e.g., job, jobs; action, actions).

Nouns ending in -y drop that letter and add -ies (e.g., supply, supplies).

Nouns ending in -s, -ch,-sh, and -x add -es (e.g., loss, losses; wish, wishes; box, boxes).

Nouns ending in -eaf, -lf, or -rf drop the -f and add -ves (e.g., half, halves; scarf, scarves).

A small number of high-frequency nouns have irregular plural forms:

Proper nouns indicate specific people (e.g., Bill Gates); geographical locations (e.g.,

Tokyo, Brazil, Asia, the Alps); titles (e.g., The Economist); organizations, companies, and

brands (e.g., The World Bank, Amazon); political parties (e.g., Labour); and schools,

colleges, and universities (e.g., Oxford University). They are always capitalized.

Common nouns refer to people, places, and things in general (e.g., student, park,

doctor). They are not capitalized unless used to begin a sentence.

Nouns can also be concrete (touchable, e.g., house, food, computer) or abstract (not

touchable, e.g., idea, belief, thought). Abstract nouns often have the following endings:

• -ance / -ence: alliance, patience

• -ism: activism, criticism

• -ity: creativity, reality

• -ment: contentment, excitement

• -ness: greatness, happiness

• -sion / -tion: extension, innovation

• -tude: aptitude, solitude

Singular

Plural

Child

Foot

Fish

Person

Children

Feet

Fish

People

19

To indicate a person who performs an action, add -(e)r to the end of a verb.

• To sell à seller

• To buy à buyer

• To grow à grower

To create a noun from a verb ending in -ect or -act, add -ion.

• React à reaction

• Object à objection

• Elect à election

Pronouns

Pronouns refer back to and replace nouns.

• Genetic engineering is among the most powerful tools of modern

science; it has the potential to affect many areas of society.

• I last saw the suitcase, which was black with a red handle, next to

the concierge's desk at the hotel.

• Many would argue that zoos are necessary to save endangered species.

Prepositions

Prepositions are "location" and "time" words; they are placed before ("pre-") nouns and

pronouns to indicate their position in time and space. Common examples include:

Prepositional phrases consist of a preposition followed by a noun or pronoun.

• Today, most people get their news from the Internet.

• The misuse of genetic engineering is a serious concern.

• You can wait for my brother by the taxi stand outside the airport.

about

above

across

after

around

at

before

below

beneath

between

by

for

from

in

of

on

out

to

under

with(out)

20

Adjectives

Adjectives modify nouns and other adjectives. They are placed before these words.

Remember that English adjectives are invariable; their endings do not change based on

whether the nouns they modify are singular or plural.

Correct: Employers’ requests for personal information can pressure job

applicants to provide false statements.

Incorrect: Employers’ requests for personal information can pressure job

applicants to provide falses statements.

When adjectives are used with "being" verbs, they are placed after the verb.

Correct: As a result of new technologies that allow employees to work at any

time, many jobs are becoming increasingly stressful.

Certain endings are commonly associated with adjectives:

• -ic: basic, fantastic

• -ful: eventful, hopeful

• -ive: creative, expensive

Adverbs

Adverbs modify verbs, adjectives, and other adverbs.

Most adverbs are formed by adding -ly to the adjective (e.g., slow, slowly). However,

many adverbs indicating time and frequency are not based on an adjective form and do

not end in -ly (e.g., always, never, sometimes).

Correct: Property values have risen sharply in recent years. (modifies verb)

Correct: Video games can be highly addictive for children and teenagers.

(modifies adjective)

Correct: I do my best to exercise very often. (modifies adverb)

21

22

Basic

Conventions

and

Punctuation

23

1. Paragraphs

Your essays must be divided into paragraphs. While your introductory and concluding

paragraphs can be very short, around two sentences, your body paragraphs should

consist of at least four or five sentences and be approximately the same length. (This is

somewhat flexible in General Training Task 1 letters.) For Task 2 essays, you should plan

to have two well-developed body paragraphs.

2. Capitalization and Spacing

Punctuation marks should immediately follow words, without a space. They should be

followed by a space. A response that does not follow standard rules for capitalization

and spacing will immediately give the person marking your essay a very poor

impression, and is almost certain to receive a score in Band 6 or below.

Correct: When students go to university, they can meet people from

around the world.

Incorrect: When students go to university,they can meet people from

around the world.

Incorrect: When students go to university , they can meet people from

around the world.

Incorrect: When students go to university ,they can meet people from

around the world.

Always capitalize:

• The first word of every sentence

• The word I

• Proper names (people, places, organizations, languages)

Correct: Technology affects nearly every aspect of our lives. In fact,

its consequences are virtually impossible to avoid.

Incorrect: technology affects nearly every aspect of our lives. in fact,

its consequences are virtually impossible to avoid.

24

Correct: Although globalization has numerous detractors, I believe it

has many positive aspects.

Incorrect: Although globalization has numerous detractors, i believe it

has many positive aspects.

Correct: In recent years, Apple devices have become extremely popular

among consumers worldwide.

Incorrect: In recent years, apple devices have become extremely popular

among consumers worldwide.

Do not capitalize non-proper nouns or other parts of speech, not even for emphasis.

Correct: A good diet not only helps people slim down, but it also helps

them become healthier overall.

Incorrect: A good Diet not only helps people slim down, but it also helps

them become healthier overall.

Correct: A good diet does not force people to restrict calories to the

point at which they are constantly hungry.

Incorrect: A good diet does not force people to restrict calories to the

point at which they are constantly Hungry.

Non-proper nouns after a comma or semicolons are not capitalized.

Incorrect: On the other hand, People should not choose a diet that forces

them to restrict calories excessively.

Incorrect: Both diet and exercise are important aspects of a healthy

lifestyle; Therefore, people should make an attempt to eat

well and be physically active.

25

3. Apostrophes

Possessive, singular noun or an irregular plural noun: apostrophe + -s.

Correct: One can learn a lot about a country's culture through its food.

Incorrect: One can learn a lot about a countries culture through its food.

Correct: Excessive screen time harms people's ability to pay attention

.

Incorrect: Excessive screen time harms peoples' ability to pay attention.

Possessive, regular plural noun: -s + apostrophe

Correct: Teenagers' preferences in terms of food, hobbies, and music

are often strongly influenced by their friends.

Incorrect: Teenager's preferences in terms of food, hobbies, and music

are often strongly influenced by their friends.

Note that the use of apostrophe + -s rather than of + noun to indicate possession can

make your English seem more natural.

Standard: My brother’s car is a blue Toyota.

Avoid: The car of my brother is a blue Toyota.

Apostrophes are also used for contractions between pronouns and verbs.

It's = it is

You're = you are

They're = they are

Correct: The concert starts at 8pm, and I think it's (= it is) going to be

a lot of fun.

Incorrect: The concert starts at 8pm, and I think its going to be a lot

of fun.

26

4. Numbers*

Nouns following numbers other than one (including zero) must be pluralized.

Correct: They expect 500 guests to attend the wedding.

Incorrect: They expect 500 guest to attend the wedding.

With the exception of times of the day and dates, numbers smaller than 10 should be

written out in words.

Correct: I will be going to Auckland on a business trip in two weeks.

Incorrect: I will be going to Auckland on a business trip in 2 weeks.

Numbers 10 and above can be written in numerals or in words.

Correct: Technology affects nearly every aspect of life in the 21st century.

Correct: Technology affects nearly every aspect of life in the twenty-first

century.

In specific numbers, words denoting large quantities such as hundreds, thousands,

millions, billions, etc. are not pluralized. (Note that with millions, billions, and higher, the

number can be written in either numerals or words.)

Correct: The Tokyo metropolitan area has almost 40 million inhabitants.

Incorrect: The Tokyo metropolitan area has almost 40 millions inhabitants.

However, unspecified quantities involving thousands, millions, billions, etc. are pluralized

when followed by of + noun.

Correct: Many large cities have millions of inhabitants.

Ordinal numbers: 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th, 6th, 7th, 8th, 9th, 10th.

Correct: I will be arriving in Auckland on 7th June (Br.) / June 7th (Am.) at 5pm.

Incorrect: I will be arriving in Auckland on 7nth June at 5pm.

*For a more in-depth discussion of numbers, see Chapter 53.

27

5. Register: Formal vs. Informal

Unless you are asked to write a letter to a friend in GT Task 1, in which case you can use

informal language, you should use the same type of moderately formal writing that you

would use in any normal academic or professional context.

Even in an informal letter, you cannot use the type of slang or ultra-casual language you

might use in a real-life text message or social media post.

With the exception of titles that are normally abbreviated (e.g., Mister), words should be

spelled out fully. In addition, you should not use symbols such as the ampersand (&) in

place of words.

Correct: I received the home-assembly kit for the dresser I ordered, but

unfortunately several pieces were missing.

Incorrect: I received the home-assembly kit for the dresser I ordered, but

unfortunately several pcs were missing.

Correct: When students go to university, they can meet people from

around the world and be exposed to new cultures and traditions.

Incorrect: When students go to university, they can meet people from

around the world & be exposed to new cultures & traditions.

When giving examples, do not use e.g., i.e., etc., or and so on.

Correct: I believe that people should make more of an effort to consume

healthy foods such as salads and fish.

Incorrect: I believe that people should make more of an effort to consume

healthy foods, e.g., salads and fish.

Incorrect: I believe that people should make more of an effort to consume

healthy foods, such salads, fish, etc. / and so on.

28

When a title is not part of a proper name, it should be written out.

Correct: I was unable to attend the meeting yesterday morning because

I had an appointment with my doctor.

Incorrect: I was unable to attend the meeting yesterday morning because

I had an appointment with my Dr.*

In formal writing, phrases such as it is and did not are written out; the contracted forms

(it's, didn't) are not used.

Correct: I believe that it is necessary for schools to offer physical

education classes in order to help children stay healthy.

Incorrect: I believe that it's necessary for schools to offer physical

education classes in order to help children stay healthy.

On the other hand, if you are instructed to write an informal letter, you should make sure

to use contracted forms along with more familiar language. It is also acceptable to include

some non-contracted forms.

Correct: You’ve been such a great host, and I really want to thank you

for all your help.

Incorrect: You have proved to be a very gracious host. Therefore, I wish

to convey my regards for your assistance.

In addition, exclamation points are not normally used in formal writing (although they are

fine to use in informal Task 1 letters).

Correct: Many people believe that governments should spend more on

defence than on social benefits; however, I do not agree with

this view.

Avoid: Many people believe that governments should spend more on

defence than on social benefits; however, I do not agree with

this view!

*In instances where abbreviations of titles are permitted, American English places a full stop / period after

the title (e.g., Mr., Ms.), whereas British English does not (e.g., Mr, Ms).

29

Note that phrasal verbs are often associated with informal writing, while single-word

verbs are generally associated with more formal writing.

Phrasal (Less Formal)

Single Word (More Formal)

Ask

Bring back

Clear up

Come up with

Deal with

Figure out

Get back to

Get up

Point out

Throw away

Inquire / Enquire

Return

Clarify

Invent

Manage

Determine

Respond

Awaken

Mention, Emphasize

Discard

Other common informal vs. formal words to know include:

Less Formal

More Formal

A lot / Lots

Big (e.g., problem)

Buy

Folks

Get

Guy

Keen (Br.)

Kid

Reckon (Br.)

Rough / Tough

So, Really, Totally

Sort of

Stuff

Many, Numerous

Major, Serious, Significant

Purchase

People

Receive, Become

Man

Eager

Child

Believe

Difficult, Hard, Challenging

Very, Extremely

Somewhat

Things

30